|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Lincoln and Lorimer: By David W. Scott

Illinois voters have not always elected their United State senators. The first year was 1914, after states ratified the 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This amendment changed the method of picking Senators from selection by the state legislatures to election by the people. Two of the most interesting and important cases of the selection of United States Senator by the Illinois General Assembly occurred in 1859 and 1909. The first was the selection of Democrat Stephen A. Douglas over Republican Abraham Lincoln, which took place two months after the General Assembly was elected in November 1858 Just prior to this election, Illinois Republicans had taken the unusual step of endorsing a senatorial candidate. The second case was the selection of William Lorimer in 1909. It took the General Assembly more than 4 months and 95 votes before Congressman and Republican Party leader Lorimer got the necessary majority. However, the U.S. Senate ultimately removed him from office in 1912 following national attention to allegations that he owed his selection to the bribery of some state legislators. Origins and processes of selecting senators The Articles of Confederation provided a precedent to give state legislatures the job of selecting United State senators. Under the Articles, state legislatures selected members of Congress. Although the Constitution of 1787 created a House of Representatives to be selected by the people, for the Senate, it retained the selection method of the Articles.

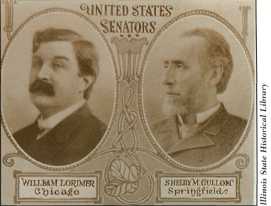

Over time, with the growth of democratic attitudes, expectation rose for more popular participation in the process of selection of public officials. By the first decade of the 20' century, popular support for direct election of Senators was high. During this period, both Illinois political parties endorsed selection by the people. In the 122 years of selection by state legislatures, Congressional laws set the rules for the choosing of Senators. Congress wanted state legislatures to get at the task right away and required them to make senatorial selection a priority upon their convening. If no person received a majority in the House and the Senate voting separately, then national law called for a joint session with a majority vote of the combined chambers needed to select a senator. In order to expedite the process and avoid a prolonged deadlock, the law j stated that votes be held each day the legislature is in session until a senator was selected. The Selection of Stephen A. Douglas It is not widely understood that it was the General Assembly that selected Stephen A. Douglas for Senator in 1859 over Abraham Lincoln following the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858. The process that led to the Douglas selection for his third term as United States Senator from Illinois was both significant and unusual and not only because of the debates. In addition to the usual practice of nominating those candidates for statewide office subject to a vote of the people, the Republican state convention at its June 1858 meeting took the unusual step of endorsing a candidate for senator. It was only the second time in American history that a state party convention nominated a candidate. The 14 Illinois Heritage 1858 endorsement was intended to be binding on Republican legislators. The procedures was so unprecedented that it attracted much attention. A Philadelphia editor call this "dangerous innovation" a "revolutionary effort to destroy the true intent and spirit of the Constitution." Lincoln accepted his party's nomination with his "House Divided" speech. The purpose of the convention endorsement was to give a clear signal to Eastern Republicans that Illinois Republicans would never unite behind the Democrat Douglas. Influential New York newspaper editor Horace Greeley was the most ardent advocate of the view that Republicans in Illinois should not challenge Douglas. A number of Republicans were impressed with the Greeley position, so Illinois party leaders wanted to counter any moves away from their recently formed party to the Democrats and Douglas. Thus the convention endorsement was to provide a focus and sense of unity early in the process. Lincoln's previous effort to be senator reflected the normal pattern up to that time of delaying announcement of senatorial candidacy until after the November elections. Lincoln wrote letters expressing his interest to legislators immediately following the November 1854 elections. However, his effort was unsuccessful. After a number of ballots by the General Assembly, he concluded he did not have a chance of being selected. He then urged his supporters to vote for Lyman Trumbull, thereby giving Trumbull the necessary majority on the tenth ballot. The 1858 campaign was shaped by party activists who worked to generate a majority for their party in the General Assembly in the November 1858 elections. The seven Lincoln-Douglas debates were just a part of that process. They focused exclusively on the national issues of slavery, not on candidates and policies associated with the General Assembly. The November 2, 1858 elections for the Illinois legislature produced a Democratic majority. Some Democrats who opposed Douglas and supported the pro-southern policies of President Buchanan strove to deadlock the legislature by pressuring some southern Illinois Democrats to withhold their vote for Douglas. This strategy did not work. On January 5, 1859, Douglas was elected on the hrst ballot, 54 to 46, a straight party line vote. Although the Democrats gained additional seats in closely contested central Illinois legislative districts, there is evidence that Lincoln was the choice of the greatest number of the voters statewide. Republican candidates won the only two statewide races on the ballot. In fact, some have misleadingly stated that Lincoln won by a popular vote of 125,000 to 122,000. No such Lincoln-Douglas vote was held. Those vote totals refer to the vote for state treasurer. The rise of William Lorimer Born in England in 1861, William Lorimer was the son of a Presbyterian minister who brought his family to Chicago. His early jobs such as streetcar conductor gave him familiarity with the attitudes of people in his west side Chicago area. Lorimer demonstrated strong political organizing skills in his early work for the Republican Party. He quickly developed a following of loyal supporters and rose rapidly in the party ranks, working for the nomination and election of candidates for city and county offices and the state legislature. His party involvement led to patronage jobs with the city of Chicago. Later he organized companies that got city and county contracts.

In 1894, the voters elected him to the first of six terms in Congress. In 1895, the Cook County Republican central committee elected him chairman, "signifying his arrival as the most powerful factor in Cook County Republican politics," according to his biographer. As the most populous county, Cook sent more delegates than any other to state party nominating conventions. Lorimer's influence now extended to shaping the selection of the top statewide officials: U.S. Senator, Governor, and House Speaker. His base in the wards and his congressional district on the West Side of Chicago and near west suburbs was not the typical Republican metropolitan Chicago constituency of Protestants and middle- and upper-income residents. It had a large proportion of lower and working class people. Many were immigrants and children of immigrants — many Catholic, some Jewish. Such groups tended to vote Democratic. Much of his success is attributed to his willingness to cooperate with Democrats. Lorimer's machine-style politics offered small favors for votes, government jobs for those who worked the precincts for the party's candidates, and government contracts and franchises for businesses in return for monetary contributions. His business allies included gas and streetcar companies, meat packers, lumbermen, and brewers. Illinois Heritage | 15 Disapproving of "Boss" Lorimer were those Republicans and Democrats who considered themselves Progressives and municipal reformers —populists and good government groups who advocated nomination by primaries, public employment by civil service, and other measures. From 1895 onward, politically ambitious people had to either develop an alliance with Lorimer or form alliances to fight political battles against him. As the Republicans dominated party politics in Illinois from 1896 onward, a key part of the selection process was its senatorial endorsement. 1896 to 1902 was marked by strife between two Republican factions. One consisted of Lorimer and his Cook County machine in alliance with the state forces headed by the two governors. This "state faction" included people who held state and local government jobs controlled by state politicians. There was also a "federal faction," which had ties to the administration of President William McKinley and included as important members Illinois'two U.S. senators. This group included federal job holders such as postmasters, revenue collectors and marshals, who owed their jobs to the President, members ot Congress, and other politicians. The emergence of Dawes A major influence in the federal faction was Charles Gates Dawes. Raised in, Ohio, this young lawyer had recently moved to Chicago, and, in 1896 managed William McKinley's presidential campaign in Illinois. In opposition to Lorimer and others leaders, Dawes tirelessly and successfully organized Illinois Republicans to support McKinley in the 1896 Republican presidential nominating convention. Dawes was also an important organizer for McKinley in the general election campaign. When McKinley became President, he rewarded Dawes with the job of Comptroller of the Currency. Dawes became a close advisor and confidant of the President. Most likely he came to see himself as a future President and thought that a good stepping-stone to the Presidency was to become a senator from Illinois. For the senatorial term beginning in March 1903, Dawes positioned himself to get the nod from the General Assembly. Early in McKinley's second term, Dawes resigned as Comptroller of the Currency and returned to Illinois to run for senator. He would almost certainly have had the endorsement of McKinley at the spring 1902 meeting of the State Republican convention had the President not been assassinated in Buffalo in September 1901. McKinley's successor, Theodore Roosevelt, provided no support to Dawes. Still, using the contacts and knowledge he had gained since 1896, Dawes worked the state to round up support among those who selected and attended county conventions. These people, in turn, selected representatives to the state nominating convention, which was expected to make a senatorial recommendation to the General Assembly. The major contenders within the party were quickly reduced to Dawes and Congressman Albert Hopkins. Hopkins went into the state convention meeting in May 1902 with the backing of Lorimer as well as the support of Governor Richard Yates. Dawes's prominent supporters included U.S. Senator Shelby Cullom. This time the Lorimer "state faction" prevailed and the convention, by a vote of 1,015 to 492, requested the 43 General Assembly to convene in January 1903 to elect Hopkins. Dawes, the consistent opponent of machine boss politics in general and William Lorimer in particular, knew he did not have a chance to overcome his del cat by those who controlled nominations to state-wide office. And, in fact, the Republican legislative caucus in early January 1903 acted responsibility to their state party and endorsed Hopkins and, with the unanimous vote of the Republicans, the legislature elected Hopkins senator shortly afterward.

After his defeat at the 1902 Republican state convention, Dawes became a bank president in Chicago and never again sought public office in Illinois. Later he continued his very distinguished and influential career by serving other Presidents. In 1921 he became the organizer and first director of the Bureau of the Budget under Warren Harding. He was Vice-President of the United States under Calvin Coolidge and headed the commission in 1924 that readjusted German reparations, which became known as the Dawes Plan. As a result he won the 1925 Nobel Peace Prize. Under Herbert Hoover, Dawes was ambassador to Great Britain and became the organizer and first president of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Illinois Heritage | 17 The 1909 election of Lorimer By the Progressive Era, however, there was widespread dissatisfaction with the convention method and control of this mechanism by party organization leaders. Thus, in the first decade of the 20th century, a new element in the nomination process emerged: the direct primary in which the voters affiliated with a party selected its candidates. The primary method of nomination had widespread public support and both parties came out in favor of it.

The second use of the primary in the process of selecting senators occurred in 1908. In the Republican senatorial advisory primary, incumbent Albert Hopkins won a plurality (but not a majority) a reflection most likely of name recognition. Although the Republican state convention followed with an endorsement for Hopkins, he never secured enough Republican support in the General Assembly to get the needed majority. Lorimer, his ally in 1902 against Dawes, now refused to support Hopkins as Hopkins had recently allied himself with a candidate for governor whom Lorimer opposed - just one example of the complex shifting alliances among factional leaders during this period. The General Assembly remained deadlocked over the senatorial choice from its first vote in mid-January until late May. In early March, Hopkins s term ended, and President Taft and some leading Republicans in the Senate started to press state Republican leaders to get the vacant seat filled. In discussions at the Governor's Mansion that extended over weeks, Republican Governor Charles Deneen, often a progressive, and Lorimer, the party organization man, could not agree on a substitute for Hopkins. Together they could influence enough votes to settle the matter. Deneen turned down all of Lorimer's compromise suggestions. Lorimer tried to get Deneen himself to announce for Senator, a post normally considered a step up from Governor. There were precedents for such a move. Several governors, including Shelby Cullom, had left the Governor's chair when the General Assembly selected them senator. Deneen did not take Lorimer up on this offer. An important reason for his refusing the offer was opposition to the plan by three reformed-minded Chicago newspaper publishers, who had supported Deneen. They did not want the Lieutenant Governor, a Lorimer ally, to sit in the Governor's chair. 18 Illinois Heritage On May 26, the deadlock finally broke on the 95th joint ballot. By early May, Lorimer believed only his candidacy could end the impasse. Drawing on his extensive friendships and calling in favors owed him and his promise of patronage, Lorimer assembled a coalition of Democrats and Republicans to give him the legislative majority. His bipartisan approach, usually unembarrassed by principles or issues, was known as Lorimerism" to his foes. Lorimer's reckoning Lorimer expulsion from the Senate in 1912 helped mold public opinion that the time had come, after decades of debate, to select senators by a vote of the people, not the state legislature. It all started in April 1910 with a front-page story in the anti-Lorimer Chicago Tribune: "Democratic Legislator confessed he was bribed to vote for Lorimer for United State Senate." This southern Illinois legislator said he and several others had been paid $1,000 to vote for Lorimer. The following September, former-President Theodore Roosevelt canceled an engagement to speak at a Republican dinner in Chicago after he learned Lorimer was scheduled to attend and sit at the speaker's table. The sponsors withdrew Lorimer's invitation and Roosevelt came. His speech was an attack on political corruption in Illinois. That month the United States Senate commenced hearings on the Lorimer affair, but the Senate decided in March 1911 not to expel its colleague by a vote of 46 to 40. However, the Lorimer case was reopened following additional charges of corruption in the Illinois General Assembly associated with Lorimer's selection. Following this second series of extensive and widely publicized hearings, the outcome was changed. In July 1912, the Senate, by a vote of 55 to 28, voted to remove Lorimer from office. The testimony presented was extensive, yet contradictory. It remains unclear whether Lorimer sanctioned the dishonest use of cash or even knew anything about it. The situation is summarized by his generally sympathetic biographer, Joel Arthur Tarr "The Senate ejected Lorimer because a majority of its members believed, or at least voted as if they believed, that his seat had been acquired through corrupt means... Lorimer's identification as a political 'boss' was perhaps as crucial as the specific charges levied against him.... Since the progressive period was an age ostensibly committed to the extension of popular control and of democratic procedures, bosses were especially reprehensible."

With the 17th amendment and the primary, elected officials, party activists, and others with specific political concerns and substantial political knowledge no longer controlled the process whereby senators were nominated and chosen. Progressive era reforms that expanded participation to the electorate had in the long run the intended effect of weakening the role of party organizations. Superceding them have been much more expensive methods of competing for public office; notably, candidates' organizations running mass media campaigns. Illinois' dubious role in reform In summary, Illinois appears to have influenced the ways U.S. senators are selected. Given the fame of the Lincoln-Douglas contest, one can surmise that Illinois had some impact on the process of choosing United State senators, as party conventions in other states took on the role of recommending candidates to their party state legislative caucuses. Another influence stemmed from the widespread national attention given to the Lorimer investigations. These Senate hearings exposed to the national spotlight the political fights in 1909 within the state that led to deadlock and delay in selecting a senator. Such deadlocks across the nation over the years strengthened the case for the choosing senators by a plurality of the vote of the people — a method that insured finality. These hearings also drew national attention to the charges that bribery in the Illinois legislature gave Lorimer his Senate seat. All the unfavorable attention to the Illinois situation likely aided in the adoption of the 17 Amendment. David W. Scott of Springfield is president of the Illinois State Historical Society. This paper was originally presented at a 2002 meeting of the Evanston Historical Society at the Charles Gates Dawes House. Further Reading: Joel Arthur Tarr, A Study in Boss Politics: William Lorimer of Chicago (Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1971) Bascom N. Timmons, Portrait of an American: Charles G. Dawes (New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1953). William T. Hutchinson, Lowden of Illinois: The Life of Frank O. Lowden, Vols. I and II (Chicago, the University of Chicago Press, 1957) Richard Allen Heckman, Lincoln vs. Douglas: the Great Debates Campaign (Public Affairs Press, Washington D.C., 1967) Illinois Heritage / 19 |

|

|