|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Graham A. Peck The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 is justly famous. The saga of the act began on January 4, 1854, when Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois reported a bill to organize Nebraska territory, which lay directly west of the states Iowa and Missouri. The bill was no ordinary measure. Using language adopted from the acts that had organized the territories of Utah and New Mexico in 1850, the bill empowered territorial settlers to legalize slavery and stipulated that Nebraska should be received into the Union with or without slavery, according to their decision. This was the doctrine of popular sovereignty, and in the context of Nebraska territory it constituted a remarkable concession to slavery. The 1820 Missouri Compromise had prohibited slavery in the territory, and since that time the compromise had achieved a venerable stature in both the North and South. Repealing the compromise's antislavery provision was thus a bold and risky move. Douglas's bill soon took on an even more dramatic character. Although Douglas likely intended the Missouri Compromise's slavery prohibition to remain in force until the territorial legislature chose otherwise, thus stacking the deck in favor of free state settlers and free institutions, southern congressmen wanted to explicitly abolish the long-standing slavery prohibition. Consequently, Douglas, President Franklin Pierce, and southern senators from both parties revised the bill's wording, and on January 23, 1854, Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska bill. It organized two territories, Kansas as well as Nebraska. Kansas lay west of the slave state Missouri, and Nebraska lay west of the free state Iowa. To suspicious freesoilers, the new provision seemed to

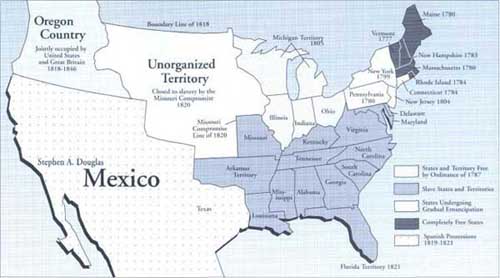

The United States at the Time of the Missouri Compromise (1820) 2

Stephen A. Douglas reserve Kansas for slavery, especially in light of an even more momentous change. The bill also declared that the "principles of the legislation of 1850" had "superseded" the antislavery eighth section of the Missouri Compromise, which was now pronounced "inoperative" (quoted in Robert Johannsen, Stephen A. Douglas, 415, 426). Although a subsequent amendment slightly modified this language, the essential meaning remained the same. The southern congressmen had made their mark on Douglas's bill. Not surprisingly, the bill outraged northerners. Protests began almost immediately, included men of all parties, and continued until the bill's passage in May. Yet Douglas was not deterred. He denounced his opponents as abolitionists and used every power at his command to drive the bill through Congress. Ultimately, with the support of presidential patronage and almost ninety percent of southern congressmen from both parties, Douglas pushed the measure through. It was a pyrrhic victory. In the 1854 congressional elections, angry northern voters decimated the ranks of northern Democratic congressman who voted for the bill, and in ensuing years conflict over slavery in Kansas contributed enormously to the rise of the antislavery Republican party and to the coming of the Civil War. For those reasons, historians have long 3

wondered why Douglas introduced the measure and fought so fiercely for its passage. Why did he behave so blindly? Various explanations have been advanced. One argument contended that Douglas sought the support of the South for the 1856 presidential race; a second claimed that Douglas sought to organize Nebraska territory in order to secure a northern route for the yet-to-be-built Pacific Railroad; a third emphasized Douglas's devotion to western development, national expansion, and the idea of popular sovereignty all of which both Nebraska bills promoted; a fourth argued that Douglas had been strongly influenced by Missouri senator David Atchison, whose proslavery constituents had desired to repeal the Missouri Compromise; and a fifth maintained that Douglas had acted rashly by introducing his first bill without anticipating southern demands for an explicit repeal. Historians have never agreed about Douglas' motives because all of these explanations have a measure of truth to them, even though all of them cannot be equally true. Thus knitting together the various interpretations of Douglas's actions presents the central challenge of reinterpreting the origins of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The solution to the puzzle lies in a largely unexplored corner of the history of the Act: Douglas' political position and ideological beliefs as a member of the northern Democratic party. Party politics considerably influenced the life of antebellum Americans. One reason was that the parties were social clubs in addition to political organizations. Party rallies, barbecues, and parades were forms of mass entertainment, and elections were venues for competition between spirited young men. On an individual level, partisan loyalties, personal friendships, and business relationships frequently intersected, so much so that the sundering of party ties could sunder personal ones. Ethnic and religious rivalries also deepened partisan loyalties. Irish and German Catholics, for instance, generally voted Democratic, while nativists and members of evangelical religious denominations tended to vote Whig. Powerful material interests and ideological convictions further cemented partisan attachments. Issues such as banking, internal improvements, the tariff, national expansion, temperance, abolitionism, and unionism resonated strongly with voters, who knew that government policy in their community state, and nation hinged on the outcome of electoral politics. For all these reasons, both rank-and-file members and political leaders were deeply devoted to their party. Douglas himself was a relentlessly partisan figure. He had been the leading spirit behind the organization of the Democratic party in Illinois during the 1830s, and the party in turn had elevated him to a position of national prominence by the early 1850s. He had demonstrated his loyalty to the party by opposing state and national banking, advocating national expansion, and laboring to preserve the perpetuity of the Union. In 1850 he had played the leading role in the passage of compromise measures that had staved off southern disunionism. By 1854 he believed with some justification that his future—and that of the nation—hinged on the continuing success of the Democratic party in Illinois and throughout the Union. However, the party's fortunes were not at their highest ebb when Douglas arrived in Washington for the 1853-1854 congressional session. To be sure, the Democrats were by far the nation's most powerful party which was indicated by the success of their 1852 presidential candidate, Franklin Pierce, who swept 4

to victory with 254 of 296 possible electoral votes. However, this electoral success masked several serious problems. Most significantly, the party was plagued by factional infighting, which soon engulfed Pierce's presidency. For instance, a bitter division over slavery in New York's Democratic party caused enormous patronage problems for Pierce, and in 1853 the New York party suffered a devastating loss to the Whigs as a consequence. The weakness of the party system also caused party leaders to fret. Although the Democrats had once enjoyed a fierce rivalry with the Whigs over economic policy, this difference had largely disappeared by the early 1850s. Mobilizing voters to go to the polls was becoming more difficult, and third-party issues, such as freesoilism or temperance, posed a growing threat. Mirroring a nationwide decline in voting, only 64.7 percent of Illinoisans voted in the 1852 presidential race, which continued a steady decline from the 82.0 percent participation rate Illinoisans had achieved in the 1840 presidential contest. The conjunction of Democratic factionalism and voter apathy raised red flags for party leaders, who knew that new issues might emerge to further disrupt the party in the absence of strong and successful leadership. Rejuvenating the Democratic party was one of Douglas's motives for introducing the Nebraska bill in 1854. Intimately familiar with Illinois' political circumstances and aware of related problems in other states, he knew that the temperance crusade had seriously damaged party loyalties in a handful of northern states. The temperance issue was uniquely destructive because its appeal cut across traditional party lines: both the Whig and the Democratic parties included men who indulged in liquor and those who abstained. Nevertheless, Douglas knew that the temperance issue, despite its great local significance, was unlikely to reshape national politics. Only a national issue could stir a nationwide debate. Consequently Douglas sought to identify and sponsor an issue that would reinforce the party loyalties of Democratic voters throughout the nation. To find such an issue, Douglas needed to look no further than Illinois. Illinois experienced enormous demographic and economic expansion in the 1850s. The railroad was the single greatest spur of those changes. A frenzy of railroad building in the early 1850s opened land to settlement, boosted immigration to the state, and enlarged Illinois' urban centers. For instance, the state's population almost doubled from 1845 to 1854, and by 1855 speculators and settlers had purchased almost all of Illinois' available public lands. Meanwhile, Chicago more than quadrupled in size and quickly became a regional manufacturing center. Yet this dramatic growth did not come without cost. Young men in rural areas found it increasingly difficult to obtain title to land, and the ranks of unpropertied urban wage laborers grew exponentially. Census records reveal that large numbers of unpropertied Illinoisans moved frequently in search of better opportunities during this decade. Given the challenging conditions of labor in Illinois, a fair number of them probably went west. 5 These political and social contexts help explain Douglas's attraction to the Nebraska bill. Concerned about what he termed the "distracted condition" of the Democratic party in 1853, Douglas intended to "consolidate" the party's power and to "perpetuate its principles" by organizing Nebraska territory and by securing a land grant for the Pacific Railroad (quoted in Robert Johannsen, ed., The Letters of Stephen A. Douglas, 267). These two measures boldly addressed the central political and social problems of the period. The Pacific Railroad promised to revolutionize national commerce in much the same way that railroads had transformed Illinois, and the organization of Nebraska would open the western plains for settlement, enabling Illinois and other crowded northern states to pour their excess population into the vast basin between Iowa and the Rocky Mountains. Here was a truly grand plan to revivify the Democratic party. The Missouri Compromise was the wrench in the works. For over thirty years it had stood as a shield against slavery's advance, yet now, with migrants trickling into Nebraska, Douglas proposed to invest territorial settlers with the power to establish slavery. This was a political gamble of immense risk and enormous consequence, but southern opposition to Douglas's earlier attempts to organize Nebraska as a free territory inclined him to take it. But southern pressure alone would never have driven him to take such a stance had he shared the antislavery convictions of northern Whigs and freesoil Democrats. Unlike them, he had no strenuous moral, political, or economic objections to slavery, and thus was willing to risk that territorial settlers might establish slavery. Moreover, Douglas hoped that the bill would permanently resolve the nation's slavery conflict by replacing antislavery extension policies with popular sovereignty. Without doubt, his unwillingness to retreat from the bill after it created a stir in the North resulted in no small measure from his conviction that national harmony required antislavery ideas to be met and mastered. In this respect, as in its advocacy of national expansion, the Kansas-Nebraska Act bore the imprint of northern Democratic ideology and politics. Like many northern Democrats, Douglas was tolerant of slavery. In 1852, he had celebrated the "common interest" that bound together America's regional economies, and in particular he argued forcefully that southern agriculture contributed substantially to American economic growth. This perspective contrasted sharply with that of the freesoilers, who maintained that slavery blighted southern society and who insisted that slave labor degraded free labor. Douglas integrated

6

slavery into the American political tradition with equal facility. Although abolitionists and freesoilers contended that the founders had dedicated the nation to liberty, Douglas insisted that the founders had in fact fought for the freedom to regulate their "domestic affairs." Thus he considered popular sovereignty a return to "the doctrines of the Revolution," leaving the people "to do as they may see proper in respect to their own internal affairs." Of course, Douglas believed that only white people had the right to control their internal affairs. Not sharing Abraham Lincoln's conviction that all men were created equal, with inalienable rights to life, liberty, and property, Douglas insisted that only men who established self-government had the right to its fruits. Since Africans in his estimation had demonstrated no such capacity for self-government in the "history of the world," the preservation of white liberty required black subordination in America. Slavery had a justifiable, even necessary, political existence. Given his views on slavery, popular sovereignty seemed a perfect fusion of democracy and Union to Douglas. Although Douglas had supported proposals in the 1840s to extend the Missouri Compromise to the Pacific Coast, he had done so in order to resolve the bitter sectional conflict over slavery extension that had resulted from the Mexican War. But he had no intellectual or moral attachments to antislavery extension policy. Indeed, he contended that the policy of running "a geographical line, in violation of the laws of nature and climate and soil," imposed political institutions on the people "contrary to their wishes." By this logic, popular sovereignty was preferable to a prohibition on slavery. Therefore he urged Congress during debates over the Kansas-Nebraska bill to "trust the people with the great, sacred, fundamental right of prescribing their own institutions." But democracy was not the only virtue of popular sovereignty. It also promised to perpetuate the Union. Once it was made a "rule of action," he argued, it would "destroy all sectional parties and sectional agitations" and assure "the peace, the harmony, and [the] perpetuity of the Union." With such an object seemingly within his grasp—an object central to the political ideology and objectives of northern Democrats— Stephen A. Douglas's willingness to risk his political standing for the Kansas-Nebraska Act is not nearly as puzzling as it has appeared to historians in retrospect. Click here for Curriculum Materials 7 |

|

|