C o l o s s u s A b o v e S t. L o u i s

Remaking the Mississippi at Melvin Price Locks and Dam

By Todd Shallat

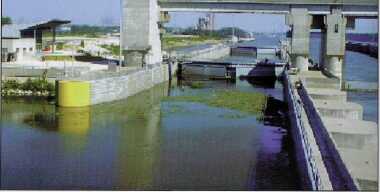

Melvin Price Locks and Dam at Alton, Illinois, opened in 1989 and was completed with a second lock in 1994.

(Digital Library, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers).

|

Melvin Price Locks and Dam stands like a river colossus in the crossroads above St. Louis, where the tugs push north toward Chicago or descend the slackwater staircase from Minneapolis-St. Paul. Even for the Mississippi the project is massive. Taller than the Gateway Arch, more sprawling than a St. Louis subdivision, it funnels the towboat freightway through 500-ton rolling gates. Eight-hundred thousand cubic yards of concrete encase 20,000 steel H-beams. That's enough steel and concrete for 30,000 homes and 17,000 luxury automobiles. Enough concrete to fill the Houston Astrodome. Enough rod and rebar to wrap the Earth six times.

"It's the largest river project in the United States," said Craig Smith, a college sophomore who worked the summer of '96 as a tour guide at Melvin Price.

The largest?

"I think it's bigger than Hoover Dam," Smith continued. "It might not look like it, but most of the structure is underwater. You have 1,200 foot guide walls that are forty or fifty feet tall. It's a billion-dollar project. Maybe 'largest' refers to the cost."

Is bigger better? Does it mean more efficient or better designed?

Smith paused. "I'm not sure. That's not usually part of the tour."

Bigger was indeed implicitly better for the engineering organization that had impounded the mile-wide river with a million-ton concrete dam. Since 1802 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had been the conduit of great expectation. Founded at Fortress West Point, the corps had been Jefferson's ploy to purge the Federalist army and nurture American science with bookish soldier-savants. Size became a standard of greatness in the corps that Jefferson founded. Committed to the massive and monumental, the corps—a planning authority, a pioneer of the benefit-cost mathematics that justified big assignments—successfully argued the link between vigorous government and industrial growth. Corps' history reads like an honor roll of engineering sensations. The world's largest independently standing coastal fortification. The world's longest masonry arch. The nation's tallest wave-swept lighthouse. Bonneville Dam, the Panama Canal, the St. Lawrence Seaway. The Washington Monument. The Capitol Dome.

"Large technology tends to promote the physical well-being of all citizens," wrote Samuel Florman, an engineer who defended the corps in 1979. But a counter force, Florman conceded, pulled hard from another direction. Even as the engineers shattered construction records with the evermore bigger and brash, President Jimmy Carter was looking to cut $2.5 billion from the federal water budget. Greens saw red in the scarlet flags above thousands of corps installations. Reformers vowed to restructure the way Congress bankrolled its dams.

Melvin Price Locks and Dam— aptly named for immovable Rep.

10 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

Melvin E. Price (D-IL) of East St. Louis, who held his congressional seat for 22 consecutive terms— recalls that watershed moment when biggest was no longer better for most Midwestern voters. It had been proposed in 1968 and funded in 1970 by the same conflicted Congress that had recently passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Its construction spanned an era when project planning became a fishbowl of open meetings and high-stakes lawsuits. Attempts to derail the project incited a challenge to principles of river construction older than Fulton's steamboat. In 1994, when the colossus was finally completed, the corps faced quandaries beyond the dam-it, ditch-it tradition: how to balance the needs of commerce against the health of a natural system, how to steward without destroying where once the streams had replenished the wetlands before progress had pushed too far.

Storm over Alton

The trouble began in west Illinois near the old landing at Alton where Lincoln had debated Douglas, where the port had become a symbol of the anti-slavery movement when five balls from a shotgun cut down abolitionist editor Elijah P. Lovejoy while a mob was torching his press. Here since 1938 the Alton barge locks had maintained step number 26 on the Upper Mississippi's 29-project slackwater staircase. Endorsed by FDR and completed for $13 million, the locks were an artifact from a golden age of big construction. Good for shipping. Good for a grain economy dependent on bulky transport. Good for the war effort in the Forties and the booming traffic at St. Louis during the postwar years. The slackwater even appeared to be good for the ecosystem. Dams, said engineers, created the elongated pools and rescued the drought-stricken fish once stranded in backwater shallows. Pools slowed bank erosion. By 1940 the navigation pools had created 194,000 acres of lakeside habitat above St. Louis—a gift from the corps to the states.

For barge industry, most of all, the slackwater was the sweetest of deals: a toll-free St. Louis to St. Paul freightway, a guaranteed nine-foot depth for barge navigation, a channel with an annual payload of 48 million tons. In 1977 the Congressional Budget Office reported that waterways were the nation's most tax subsidized mode of transportation. More than airports. More than railroads, pipelines, or interstate trucking. Even after user-fee and cost-sharing reforms of the 1980s, the federal taxpayer still paid out an estimated $500 million a year for inland navigation, about 92 percent of the tab.

What made the deal so sweet was the tax money Congress routinely provided the Corps for maintenance and rehabilitation. In 1970 Congress made a $27 million down payment on the $400 million for lock replacement at Alton. Old L&D 26 was a blowout waiting to happen. Anchored to river sand, it leaked and groaned and vibrated on a timber foundation. The outer wall in thirty years had shifted ten inches downriver. A hole dug out by the current exposed a waterlogged picket of piles. "It was like walking in a forest," a diver recalled.

And the project was badly situated. Wedged in a dangerous spot where the tows swung across the current to avoid a hump in the Illinois shore, the lock with its 600-foot-long main chamber had room for nine barges in an era when tows were pushing fifteen. Electric winches and helper boats slowly broke down cumbersome tows as they lined up for lockage at Alton. "The present lock has exceeded its design capacity," said John Swift of the Waterways Journal, a barge industry publication. Barge congestion was causing 48-hour delays.

Barge owners said they were losing $100 an hour, $160,000 a month, and the railroads were delighted. Rail revenues soared, increasing about 50 percent in the St. Louis region during the 1960s. The Western Railroads Association predicted "catastrophic economic effects" if the corps was allowed to "artificially stimulate" Mississippi navigation by replacing the locks at Alton.

Why was the new project so enormous? Why was it being designed with two giant lock chambers and enough sill capacity for barges with a 12-foot draft? Because the real objective, said critics, was a deeper, wider, 12-foot navigation channel that would quadruple the great river's freight. Challenging the corps on the grounds that rail cars were heavily taxed while barges were not, that big locks aggravated the sedimentation that clogged riparian wetlands, that they also endangered $382 million in rail revenues and 35,000 jobs, the railroad association filed suit in U.S. District Court on August 6, 1974. Twenty-one railroads enlisted against the corps' ambition at Alton. The Sierra Club and the Izaak Walton League set aside a suspicion of railroads and signed on as well. Independently the improbable partners had made little headway in Congress. Together they had passion and clout.

Railroads upset with subsidy? The irony was thick. Barge owners thundered against an estimated $700 million a year in federal support for railroads—the subsidy for hauling mail, for eliminating rail crossings, for social security transfers to rail pensions, for Conrail stock buyouts, for bailouts and giveaways dating back to Cornelius Vanderbilt and the land-scheme rail scandals that tarnished President Grant's administration. "Pure greed" was how St. Paul barge industrialist John W Lambert characterized the railroads' position.

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 11

Rail money was tainted money, and counterculture idealists, one attorney conceded, "were skittish about dealing with railroads." But they relented. Hating the corps more than they distrusted each other, bearded ecologists and rail lawyers in pinstripes shared the same apocalyptic vision of a sterile, stagnant, single-purpose towboat causeway, an Upper Mississippi remade.

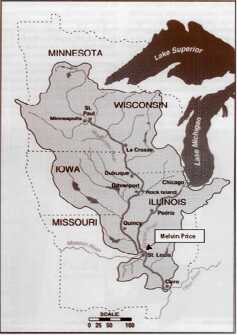

Melvin Price in the "crossroads" stretch of the nine-foot channel above St. Louis where three major tributaries—the Illinois, the Missouri, and the Ohio—enter the Mississippi -within 250 miles.

(U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Rock Island District)

|

The biggest fear in the war against lock replacement was that the corps wanted more for the river than any river could handle. More tows. More dredging. More dredge spoil dumped into wetlands. More suspended silt in the brown plumes trailing behind 10,000 horsepower motors. More sedimentation in backwater channels and sloughs. Already the locked Mississippi had lost about a fourth of its marshy backwater, a federal commission reported. Old Man was rapidly aging. Lock pools had become catch basins for the upland topsoil washed through the veins of commerce into the continent's heart.

Building a Taj Mahal

Once there was hope that big engineering might cleanse an industrial river. In 1943 the top wildlife biologist at FDR's Fish and Wildlife Service published the astonishing claim that the locks and dams had rejuvenated the great Mississippi waterfowl flyway, and that the health of the floodplain had "vastly improved." Dams had backed the river up over meadows. Lock pools had spread a leafy-green carpet of pondweed that sheltered the mallards and teals. Slackwater was also good for the mayflies. An excellent fish food, the mayfly nymphs rose like a fog off the impounded river, and they died in blankets so thick that towns cleared bridges with snowplows. Slow-water fish did well in the corps-built nine-foot channel. Carp thrived. So did blue gill, crappie, sunfish, large-mouth bass, and northern pike.

Not everything prospered, of course. Not the slough-feeding pallid sturgeon. Not the fast-water channel-dwellers like sauger and small-mouth bass; but, as General Clarke took pains to explain, "there's no use trying to perfect nature without disturbing it." Clarke chided a soft generation for expecting too much: "There were no trout in the Missouri River that Lewis and Clark explored up to Montana; it was too muddy. There were no game fish in the Colorado when Coronado gave it its name because of the red silt it bore." There would always be winners and losers on a planet ravaged by change. "We demand that [nature] be left untouched," Clarke continued in a letter to Fortune. "We also expect it to be made ideal, and justify our demands on the fictitious ground that it once was perfect and has been spoiled."

Clarke's top man in St. Louis agreed that the opposition at Alton had misread the historical trend. "Hogwash," said Col. Guy E. Jester, a future barge lobbyist. "The navigation improvements [have] actually prolonged the life of this river if you look at the history of what has gone on."

Ecologists told another historical story, documenting it for the courts. In their history the levees had ended the floods that replenished bottomland lakes so rich with nutritious plankton. Dikes constrained the river and cut off the shallow places. Dams trapped the silt and sand that smothered the spawning beds. Another concern aired in the courts was the danger of channel dredging. In 1973 the state of Wisconsin used a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) injunction to suspend a suction-cutter dredge operation that, biologists said, dumped spoil into grassy wetlands. Two years later, in a similar action, Minnesota won a suit that linked dredging to river pollution. Congress then humbled the corps with a 1977 Clean Water Act amendment that made dredgers get permits from states.

"Those silly butterfly chasers," snapped an anonymous corps official quoted in the Wall Street Journal. "Those ignorant, misguided, conceited fools, they know not what they say." In the public relations campaign that followed, the corps, said agency broadsides, was "the one Federal agency that has done more for natural resources development than any other." Committed to the principle that "nature is unified and should be managed as a system," the engineers were the "true pioneers" of waterway conservation. The campaign cited

12 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

fish ladders and boat ramps and floodway nature preserves and corps-built scenic drives. In the decade of Earth Day the corps maintained 400 water parks along 30,000 miles of public shoreline. All were proof that the capable engineers, as one writer put it, were "taking command of the environment." Engineers, said another defender, "were assisting the conservation movement for many years before the term 'environmentalism' was even coined."

Publicists "greened" the corps. Agency lawyers meanwhile maintained that maximum safety, not tonnage, was the government's primary goal. Engineers took pains to assure the fish and wildlife lobby that Congressional authorization would have to precede any attempt to accommodate larger tows with bigger locks. But corps officials had also publicly stated that a bigger and straighter fifteen-foot river channel "is recognized as a distinct need."

The Ohio River with its twenty locks was already a 12-foot channel. In fact the push for big locks went back to a 1945 Congressional resolution and a 1949 corps feasibility study. In 1968, at a public hearing in Rock Island, corpsman Walter C. Gelini had been urging channel enlargements when a Missouri conservation official questioned the impact on wetlands. "The 12-foot channel is here—today or tomorrow,"Gelini replied.

Back in a Washington courtroom it took Judge Charles Richey exactly a month to rule that fear for the system-wide impact of lock expansion was a reasonable concern. The pretense that the corps' plans for bigger locks were unconnected to the barge industry's plans for 12-foot channel was, Richey admonished, "unworthy of belief." On September 6, 1974, the judge suspended the design work at Alton. If the corps wanted oversized locks, Congress would first have to pass a law that made the Mississippi exempt from NEPA. Either that or the corps would have to appraise every significant cost of navigation improvement—the economic cost to Midwestern railroads, the environmental cost to backwater marsh grass, the cost to fish and wildlife and tourism and recreation system-wide across 1,158 miles.

|

On June 22, 1977,

Domenici sponsored a

bill that would authorize lock

replacement in exchange for

a fuel-tax user fee.

|

Quickly the corps went back to work on a supplemental EIS that considered the wider impact of bigger locks but arrived at the same two points: first, the danger to the environment was minimal; second, the old timber and concrete project was a hazard that should be replaced. Critics went apoplectic. Reader's Digest called big locks "a multibillion-dollar rip-off." A "60 Minutes" report implied that "big business" had hoodwinked "big government" into building a Taj Mahal. In the end it was all too much for Army Secretary Howard Callaway. Already infamous for his resistance to the corps' congressionally mandated wetlands protection program, Callaway, on August 4, 1976, recommended a halfway retreat: Congress, for now, would approve just one 1,200-foot lock chamber at Alton. An interagency basin commission would continue to study the need for a second chamber, and the Izaak Walton League would continued to fight it in court.

David slays Goliath

The big issue left on the table was the question of user fees. Senator Pete V. Domenici of New Mexico still dreamed the impossible dream of a pay-as-you-go charge on water freight. A lanky pitcher from Albuquerque, formerly a farm-clubber for the Brooklyn Dodgers and still game for political hardball, Domenici, age 45, fought uphill against three of the corps' senior-most waterway patrons—against Russell B. Long (D-LA) and John C. Stennis (D-MS) in the Senate, against Melvin E. Price (D-IL) in the House. On June 22, 1977, Domenici sponsored a bill that would authorize lock replacement in exchange for a fuel-tax user fee. Environmentalists wanted the fee to be 63 cents per gallon of diesel. Secretary Brock Adams of Carter's transportation department said 40 cents would suffice. Intense lobbying and negotiations further reduced the tax to 10 cents per gallon. Passed by Congress in 1978, the compromise created the Inland Waterways Revenue Act. It established a savings account for inland waterway projects. A phased-in fuel tax, in theory, would cover half of the $700 million the corps now figured it needed to replace the old lock and dam.

Ann Cooper of Congressional Quarterly saw David slaying Goliath. "Pete Domenici," cheered the reporter, "went head to head with Russell Long—and Domenici won!" But Long was the silent victor. A legend in Louisiana, the cigar-chewing, word-slurring Senator Long had a gift for seeing where the nation was headed and wading in with the flow. Long guarded a quiet respect for the renegade Domenici. Although the two politicians were a wet-and-dry study in contrast—a barge Democrat from the soggiest state in the Union, a rail Republican from the most arid—both sat on the finance committee, and there after months of arcane debate they bristled at the arrogance of the water-freight lobbyists who, conceding nothing, had stonewalled the tax agreement already approved by the House.

"We're going to pass you a bill," Long assured Domenici. And the 95th Congress delivered . . . but not before the arm-twister from Baton Rouge and House Speaker Tip O'Neill knifed into the user-fee concept, removing its fiscal heart. Ten cents was token taxation. There would be no pay-as-you-go provision, no attempt to recover any significant

(Continued on Page 22)

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 13

(Continued from Page 13)

portion of the lock project's actual cost.

The Long-Domenici agreement was tentative yet richly symbolic, a preview of the fiscal retrenchment that softened the corps to reform. In 1980 the President asked the House to suspend 125 water projects even as the contractors began driving the H-beams for the technological marvel soon to be named after retiring Congressman Melvin Price. New priorities were reshaping the Mississippi. As the image of the river evolved in the 1980s, old customers made do with less. In 1983 the Lower Mississippi Flood Control Association reluctantly shaved $100 million off a $400 million request for levees and a pumping station. In 1984 the corps spent less on construction than maintenance—a historic first.

A half century had passed since the wedding-cake sidewheeler watchmen "marked twain" north of St. Louis, two centuries since the Congress, in 1787, had stipulated that the inland waterways "shall be common highways and forever free . . . without any tax, impost, or duty."

The army's most brilliant technicians had in those formative years matted and snagged about 27,000 miles of navigable watercourses. Elevating government, they had pioneered a place for the schooled expert as a policy insider. Embracing a builder's faith in water as a pathway to progress, they were seldom politically neutral, yet good engineers well understood that logrolling for levees and locks was a ritual reserved for elected officials, a political rite. Dutiful service to a free-spending Congress had built, since 1936, more than 1,500 waterway projects. It had prevented at least $150 billion in flood damage—a payback of 7 to 1 according to corps statistics. It had remade the Mississippi into the spine of a

14,000-mile transport network that moved, annually, more than two billion waterborne tons.

Once Americans had mostly trusted their lock and dam organization to strive for a more perfect union by fixing small imperfections in God's near-perfect Earth. No longer. The politics of big engineering had shifted in the storm over Alton. Suddenly the foundation seemed hollow.

An environmental ethic

That the towboat commerce survived in the wake of the storm over Alton was proof that the nation's most savvy waterway organization had always been more than a builder of dams. There had always been romance, even regret, in the scientific mind of the army; in the wanderlust of topographer John C. Fremont who paused atop snowcapped peaks to contemplate noble insects; in the remorse of Yellowstone explorer William F. Reynolds who protested "the entire extinction" of America's buffalo herds; in the Faustian anguish of postwar Chief Engineer Samuel D. Sturgis, Jr., who built the monumental but pined, nevertheless, for the mossy stream in the pungent forest, the lost wood of his youth. "Man cannot dominate," Sturgis insisted in 1953. Addressing a Milwaukee convention of fish and game commissioners even as the corps was elsewhere selling the "unified plan to convert a wild and destructive river into a tame and beneficial one," Sturgis, looking forward, looking backward, straddled the distance between what engineering had done for the nation and what the future-repenting republic would make engineering become.

It was not faith in the gospel of progress that unsettled a builder like Sturgis. It was blind faith.

|

Henceforth the Corps, the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service, and five

state conservation agencies would

be required to monitor and

mitigate the system-wide effects

of slackwater navigation.

|

"All of us here at the corps in one way or another have taken on an environmental ethic," said Lt. General Henry J. "Hank" Hatch, the corps' 47th commander. Hatch had won his command in the wake of 1986 court-ordered compromise that pledged $190 million for environmental projects. Henceforth the corps, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and five state conservation agencies would be required to monitor and mitigate the system-wide effects of slackwater navigation. Congress called it the Mississippi River System Environmental Management Program (EMP). In 1987 the quid-pro-quo was $245 million to expedite navigation with a second, albeit smaller, lock chamber at Melvin Price. Immediately the wildlife service wanted to know just how the corps was planning to offset the impact of double locks. By the year 2038, according to Interior Department estimates, the engineering expense of protecting the natural river would reach $3.75 billion. Larry R. Gale, director of the Missouri Department of Conservation, was "greatly troubled" that a second lock chamber had been authorized before Congress knew the long-term costs. "History," said Gale, "has repeatedly shown the extreme difficulty in securing after-the-fact funding for a mitigation plan."

Sixteen years after its reauthorization the colossus stood completed at last. On June 18, 1994, a flotilla of pleasure boats joined the Saturday crowd on the Illinois side of the river to watch the corps work its auxiliary lock. Completed for $1 billion, more money than the corps had ever spent at a single location, Melvin Price was now big enough to accommodate a super-sized tow of fifteen barges in single lock operation. What had been a two-hour process

22 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

now took 45 minutes. Over the next six years the Upper Mississippi's annual waterborne payload would jump about 10 percent to 83 million tons. But critics had darker numbers: 204 species of fish and mussels endangered by lock pool sedimentation; $32 million annually to freshen backwater channels and mitigate the habitat loss.

That the commerce outweighed the cost was never seriously questioned by the retiring chief engineer. In 1992 after 33 years in the army, General Hatch conceded that yesterday's corps perhaps had taken a too narrow view of the national interest. River construction, nevertheless, remained "absolutely essential." If economies were to grow, if the wealth of all nations depended on economic interdependence, the corps would find green solutions to hazardous navigation. The corps would embrace "environmental sustainability." Engineers henceforth would be looking "beyond the law" and "well beyond past practices to see how we might apply our skills to solving the world's environmental problems—and how we might make our work more environmentally sound." Eco-engineering would become a "Pearl Harbor" to rescue the planet. Tree planting, marsh building, wildlife preserves, beach restoration, wastewater treatment, toxic waste clean-up, dredge spoil research, and a vastly expanded wetlands permitting program would soon make the corps, said Hatch, the "world leader" of green innovation. Nation builders would "take command of the environment," returning "manscape" to landscape and restoring a sustainable Earth.

Dislodged from its bend in the river, searching for mission and purpose, the corps, said The Washington Post, had pulled off "the ultimate bureaucratic miracle." Even former adversaries like Norah Deakin Davis, an author who had hammered the corps with nostalgia for rushing rivers, came away cautiously optimistic after meetings with Hatch. "The Army Engineers want to shed their old image and become the good guys," wrote Davis in American Forests. The nation builders, it seemed, had learned to think cosmically about the impact of single projects on thousand-mile river systems. Less arrogant, they had "partnered" with fish and game agencies and environmental clients. More imaginative, they had cut V-notches into rock dikes to rescue the murky pools from backwater sedimentation. They had built perches for eagles, islands for shore-birds. They had scored miles of skinny grooves into concrete river-bank revetment so that insects and protozoa could better sustain the aquatic food chain. They had rolled out a soft, green carpet of marsh grass by fluctuating the water levels behind corps locks and dams. "The whistle has blown and the army has wheeled," wrote Hope Babcock, an Audubon Society critic. In 1992 the corps spent $260 million on so-called environmental projects— about 8 percent of its $3.3 billion budget for civil works.

Yet the weight of another tradition still drove the construction giant. "Engineers can be imaginative, risk-taking people, but most of the time," wrote science journalist Robert Pool, "they color inside the lines."

Engineers clung to tradition because risk invited disaster, because their positivism grated against the gloom of biological science, because material progress through water construction was still their fundamental reason for being. Even disarmingly earnest General Hatch was realist enough to admit "that [environmental compliance] doesn't mean I'm going to destroy the economics of a project that is needed for economic reasons by overburdening it with the environmental aspects." Hatch still had to believe that engineering would fix engineering. He still thought builders should build. More coastal marsh? The corps would use dredge material to shore the sinking lowlands. More wet prairie? The corps would build a prairie educational center in the very shadow of its biggest lock.

In these ways the corps on the Mississippi remained an agency in-between: between the promise and peril of technological modernization, between Hamiltonian commitment to industrial progress and Jeffersonian longing for the greener, older, more erratic and chaste Mississippi lost to the industrial age. "We tried to stay in the middle," said Owen Dutt of the St. Louis District, a planning chief who spent more than a decade in the thick of the fight over Melvin Price. "It was the wild-eyed environmentalists versus the American Way—that's how the shippers saw it." Did the corps manage to remain impartial? "We thought so but the courts said otherwise. In retrospect, I guess they were right."

Dutt makes the essential point about the in-between organization. Bureaucracy seeking the middle ground might still take a position. And that is why the ideology of the corps still rises off the river like mayflies: in Vicksburg where an engineer refused to concede that levees and dams had subsidized agriculture; in Alton where I was informed that the corps had "built" Yellowstone; in St. Louis where an expert said the corps had rescued a forested river degraded by wood-burning steamboats; in Memphis where a public relations man said the agency had been an environmental crusader since the time of Lewis and Clark.

It takes distance to see ideology. Historical distance. Only in retrospect is it possible to understand how inextricably environmentalism has become intertwined with the strands of two different dogmas. One is the hopeful view that engineering might yet revive a vanishing landscape. The other holds that humanity can never replicate the rhythms of nature and our safest course is never to try.

Todd Shallat teaches history at Boise State University in Boise, Idaho, and is a new contributor to Illinois Heritage.

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 23

|