Corn hustlers

How Decatur Starchworkers became Chicago Bears

By Mark W. Sorensen

In the fall of 1920, after the newly formed Staley semi-pro football team had won its first four games, Decatur Daily Review sports editor Howard V. Millard opined, "The playing of the starch-worker eleven has brought

"Iron man" Joe McGinnity

|

Decatur more publicity than any other one thing that has happened in years." That was exactly the result A.E. Staley, Sr. hoped for when in February he had persuaded twenty-five year old George Halas to move to Decatur and create a football program that would rival the industrial team of any company in the nation. Earlier, Gene Staley had "Fellowship" industrial league baseball and football teams organized and in 1917 had hired former professional pitching star "Iron Man" Joe McGinnity to coach the diamond nine.

This 1920 Staley's team photo was taken in Decatur before all of the players arrived. George Halas (front row center) stated in his biography that ball carriers and receivers had broad vertical stripes of rough material sewn on their jerseys to keep pig skin from slipping off their chest. Halas claimed the uniforms were dark blue and orange, the Staley Journal reported them as red. Leather helmets were optional.

|

Rock Island native Joseph Jerome McGinnity had played a season of semi-pro ball in Decatur in 1894 earning about $5 per

game. Although his moniker, "Iron Man," originated from his off-season foundry work, the future Hall-of-Famer was famous for starting, and winning, both games of a double-header. After his stint at Staley's, he pitched in the minors until he was 54 years old.

On February 2, 1920, A.E. Staley sent employee George Chamberlain to Chicago to meet with former University of Illinois athlete George Halas at the Sherman House (now site of the State of Illinois — James Thompson Center) and make him an offer to come to Decatur. Halas was recruited to play on the Staley baseball team and to create, coach, and play on an upgraded football team. It was agreed that he would receive a weekly salary of $50 for work in the plant as a "scale house clerk," responsible for weighing deliveries of corn. Halas demanded that any athlete he recruited would be given a job at that pay, be allowed two hours off each afternoon for football practice, and receive his share of the gate receipts—a total compensation package that turned out to be over $2,000 for four months work. Sixty years later Halas said: "Without Gene Staley, there never would have been the Chicago Bears .... Decatur, Illinois was the real birth place of the Chicago Bears, and the Staley company was indirectly and partially responsible for the founding of the National Football League."

George Halas misses the boat

Augustus Eugene Staley, Sr. was born in North Carolina in 1867 and by age 17 was a traveling salesman. In 1906 he incorporated his

10 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

George Halas

|

business of boxing "Cream Corn Starch" in Baltimore. Looking to expand his company beyond the control of his suppliers, Staley found a defunct corn processing plant in Decatur. He bought the Wellington Starch Company on the east-side of town in 1909 and began production March 12, 1912. Frequently described as a man of confidence and vision, his legacies include the creation of Lake Decatur and bringing the soy bean to central Illinois in 1922. Staley loved sports and thought company teams would stimulate employee morale and spread the Staley name across the county in a positive way.

George Halas was born to Czech immigrants in Chicago in 1895. He and his brothers helped with the family business and became gifted athletes. He attended Crane High School and because of his size played tackle for 4 years on the "lightweight" football team. Weighing only 120 pounds when he graduated in 1913, he worked at Western Electric Company for a year before matriculating to the University of Illinois. Halas played basketball and baseball for the Illini while pursuing an engineering degree. Coach Bob Zuppke thought the now 140-pound Halas still too small for freshman football, but allowed him on the team the next year. Both gritty and resilient he broke his jaw his sophomore year and fractured his leg as a junior. In the fall of 1917 he made it through a full season and was part of the Big Ten Championship team.

After his sophomore year in Urbana, Halas went back home to work and play baseball at Western Electric's Hawthorne Plant. On July 24, 1915, the team was to play in Michigan City, Indiana, at the company's annual picnic. Halas was ticketed on the first ship to leave the Chicago River but he left home late and missed the now capsized Eastland that had taken 812 lives. However, George Halas' name appeared on the official death list and was printed in the newspaper. The following Monday fellow Tau Kappa Epsilon fraternity members Elmer Stumpf and Walter Straub went to pay their respects at the Halas home and were shocked when brother George answered the door. Fifty years later Halas told an interviewer, "When I missed connections on the ill-fated Eastland, I realized I was a very lucky man."

Allowed to graduate early from the U of I in 1917, Halas enlisted in the Navy and was assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Lake Bluff where he played right end on the "Bluejacket" football team. This group of young college stars started the 1918 season with wins over Iowa and Illinois. Even though they then tied Notre Dame, the Irish's first-year coach, Knute Rockne, praised the team as the best he had ever seen. After beating a Rutgers team led by All-American Paul Robeson, then Navy and Purdue, the Bluejackets were selected to play in the 1919 Rose Bowl against another service team, the Mare Island Marines of Vallejo, California. In the only all-military Rose Bowl game, Great Lakes won 17-0. Even though his teammate Paddy Driscoll had a superb game, Halas was named MVP of the winning team. Years later he reflected, "That was the only game I ever starred in." According to football historian Joe Ziemba, the many military football squads during World War I "had a huge impact on the birth of the NFL," as athletes recognized for the first time that they could continue to play football after college.

His navy career over, that spring, Halas signed with the New York Yankees baseball team as a right fielder but only played in 12 games before hurting his hip sliding into third base. Shipped to the minors, he gave up pro ball for a job as a bridge engineer with the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad. When offered the position at Staley's in 1920, Halas was happy to get back into sports. After all, a return to the Yankees didn't look too promising as they had just purchased the contract of some Boston Red Sox pitcher turned right fielder named George Herman Ruth.

Soybeans and athletes

That summer Halas played outfield on the Staley Fellowship Industrial League team and led the club with a .315 batting average. In the middle of the season he took off around the Midwest on what he later referred to as "probably the first professional football recruiting journey in history." With the blessing of A.E. Staley, he offered recent college stars a chance to have a secure job and still play football. On Thursday night, September 16, 1920, Halas and Staley executive Morgan O'Brien took the train to Ohio with the object of organizing a professional football league. Meeting in a Hupmobile Auto showroom in Canton, Ohio on September 17, the agile Halas sat on an auto running board and in two hours helped organize the American Professional Football Association with the legendary Jim Thorpe as president. Returning home, Halas played his last semi-professional baseball game of the season on Sunday as the Staley "Starch Workers" defeated the oily Lawrenceville Havolines 4-0. His future Hall-of-Fame career as a professional football player, coach and owner began at practice the next day.

Halas only had two weeks to get his newly assembled men in shape for their first game. At only five feet five inches tall and one hundred forty-six pounds, Decatur native

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 11

Charlie Dressen had been the 1919 Staley Fellowship team quarterback. However, with the signing of Pennsylvania QB Walter "Pard" Pearce and star University of Illinois (they were also Big Ten Football Champions in 1919) half back Edward "Dutch" Sternaman, Dressen got very little playing time that season. A second baseman on the Staley baseball team, Dressen went on to play professional baseball for the Cincinnati Reds and became famous as the manager of the 1952 and 1953 Brooklyn Dodgers.

After a week of getting the kinks out, the Staleys had a light scrimmage against the Millikin collegians on Tuesday night, September 29, while showing off starch workers Roy Adkins and Ranny Young, two recent Millikin alums. Future MU athletic director Flank Gill was on the 1919 and 1920 undefeated Millikin teams and scrimmaged that week against the pros. Sixty years later he recalled "Staley's had some of the best college players around. They were like a college all-star team." Newsman Howard Millard wrote that week, "It looks like the best bit of material ever gathered in Illinois."

On Sunday, October 3, 1920, the "Moline Tractors" came to town and played that afternoon at Staley Field, on the northwest corner of Eldorado and 22nd Street. At least 1500 spectators climbed into the stadium bleachers to watch Decatur win 20-0. The next morning the Decatur Herald proclaimed "the Staley eleven will be a high class aggregation and one that will give any professional team in the country a battle." A week later, while Halas limped along the sideline with a sprained ankle, Staley crushed the "Kewanee Walworths" 25-7. By this time Nebraska All-American

Man down, cleats up

Fritz Pollard's fight to win a place for black athletes in pro football

By Mark Sorensen

Frederick Douglass "Fritz" Pollard was born in Chicago January 27, 1894, and starred on the football, baseball and track teams at Lane Tech High School. His mother was Native American and his father was an African  American who fought in the Civil War. Pollard excelled in the backfield at Brown University and was the first black to play in the Rose Bowl. American who fought in the Civil War. Pollard excelled in the backfield at Brown University and was the first black to play in the Rose Bowl.

After serving in World War I he played professional football for the Akron Pros in 1919. The following year he led the new league with seven touchdowns. George Halas wanted the Decatur Staleys to be the undisputed champions that year and challenged the Akron team to a "championship" game in December 1920 in Chicago. According to a 1976 filmed interview, Pollard remembered "George Halas organized a team there, and we had won the world championship in Akron. We were on our way to California for exhibition games when George Halas sent word to me to ask if we could stop off in Chicago and play. I didn't like the idea because George Halas wasn't the friendliest fellow in the world and I didn't like the idea that he didn't allow any blacks to play on his team. But I was going to Chicago and Chicago was my home and I couldn't turn it down." Played before 12,000 fans, the game was scoreless and both teams claimed the championship. However, that winter the league awarded the championship to the undefeated Pros, and the Rock Island Argus selected Pollard as first team All Pro. The next year the Decatur/Chicago Staleys did not play Akron — and won the title.

Only a few blacks played pro football at that time and many of the players and fans thought even a few was too many. In a 1979 interview Pollard, who played at about 150 pounds, stated that he created a strategy to protect himself after plays to prevent piling on. When he was tackled, he would quickly spin onto his back and stick his cleats and knees into the air above him. In 1921 Pollard became the first black professional football coach and led the league in rushing with 265 yards. After playing for several other integrated teams he began a career in business. As the number of blacks in the NFL dwindled, he formed several all black teams and looked for exhibition games. There were no blacks in pro football from 1934 to 1946 and Pollard publicly stated that Halas was partially to blame. Halas denied this in the 1930s, but the first black player in Bears history was Eddie Macon in 1952.

There has been a movement since the creation of the Pro Football Hall of Fame to have Pollard included. In 1978, sports columnist Jerry Izenberg wrote of Pollard, "It is a shame and a scandal that more young people do not even know his name. He is not a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. That is an incredible oversight -almost as incredible as the chain of events which form Pollard's own personal history." George Halas was in the first class admitted in 1963 and several of the Decatur Staleys along with Paddy Driscoll were inducted in years two and three. On August 7, 2005, Fritz Pollard, who died in 1986, finally entered the Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. Sixteen of his early league contemporaries had been enshrined before him.

|

12 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

end Guy Chamberlain had joined the team. In 1956 Halas would state that "Guy Chamberlin was the greatest end of all time," and in 1965 he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

"The Staley fans went wild with joy, while the Tri-City supporters saw defeat as their pets."

The Starchworkers hit the road

Their first road game was with an actual Professional League team, the Rock Island Independents. A special train was chartered and 200 Decatur boosters joined fans from around the state to see the favored Independents. Halas and the other ten starters played the entire game on both sides of the ball with no substitutions. The Staley Fellowship Journal reported, "Without doubt the greatest achievement in the history of Staley athletics occurred Sunday, October 17, when George Halas and his wonderful starchworker eleven humbled the famed Rock Island Independents, to a tune of 7 to 0, before 5,000 fans in the Island city."

The following Sunday the Starchworkers played their first game in the newly named "Cubs Park" at the corner of Clark and Addison streets in Chicago. Using only one substitution, Decatur beat the "Chicago Tigers" ten-zip in front of 5,000 of some of the country's new professional football fanatics and then claimed the "Championship of the Middle West." Over the course of the next two months, while Halas played with a fractured cheekbone, Staley beat Rockford 29-0; tied Rock Island in the mud at 0-0 in front of 5000 rowdy people; defeated the Minneapolis Marines 3-0 on a frozen field; and humbled the Hammond Pros 28-7 at Staley Field.

In his 1979 biography, Halas claims that many fans bet on games and that feelings ran especially high before the November 7, 1920, rematch against the Rock Island Independents. Many Decaturites had cleaned up betting on the underdog Staleys in the first game. In addition, the Decatur team injured two Independents on October 17 who still couldn't play. Rock Island brought in extra seating for the game in Douglas Park. Two days before the kickoff, the Rock Island Argus and Daily Union reported that because of the previous injuries and the fact that six of the team couldn't leave work to attend practices, "...the Independents are fostering only a furtive hope that they will be able to stop the Staleys...."

Halas later reminisced that the Rock Island team, and local low lives, were out to get Decatur center

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 13

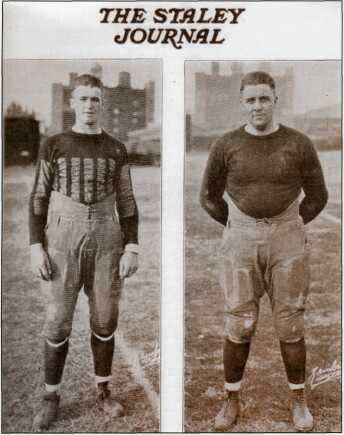

This 1921 photo shows second-year Staley players Guy Chamberlin (left) and George Trafton, both later elected to the NFL Hall of Fame. Chamberlin was an All-American end from Nebraska who played and coached on five NFL Champions in the twenties. Chicago-born Trafton was called the "meanest, toughest player alive" by future Bear teammate Red Grange. One reporter stated he was strongly disliked in every NFL city, with the exception of Green Bay and Rock Island. In those places, "he was hated."

|

(and future Pro Football Hall of Famer) George Trafton. Therefore, Halas did everything he could to protect his player and the gate receipts from harm. However, the next day, after the Staleys knocked another four Independent players out of the game, Argus sports writer Bruce Copeland wrote: "CRIPPLES HOLD STALEY TO 0-0 TIE"----"Unsportsmanlike Conduct of Starchmen an Utter Affront to Fair Name of Clean Sport." According to Copeland, the Staleys used "Stone-age football tactics," while the injured Rock Island captain "urged his players to greater pluck against swinging fists, vicious piling and wanton kicking under the piles." None of this was ever reported in the Decatur papers, although Halas confessed in his biography that because he personally weighed so little, he often held his "opponent whenever the umpire wasn't looking."

After a victory on Thanksgiving Day 1920, the Decatur Staleys lost to the Chicago Cardinals and legendary "drop-kick" specialist "Paddy" Driscoll on Sunday, November 28 in Normal Park at 61st and Racine in the Windy City. The following Sunday at Cubs Park (now Wrigley Field), over 8,500 Came out to see Staley defeat the Cardinals 10-0 and claim the professional "Mid-West Football" title. (John "Paddy" Leo Driscoll was born in Evanston and was a star athlete both in high school and at Northwestern. After playing poorly in 13 games for the Chicago Cubs in 1917, he joined the navy, was assigned to Great Lakes Naval Station, and became friends with Halas for life.)

Halas then invited the Eastern champion Akron Indians to a showdown in Chicago. On December 12, with Paddy Driscoll now playing (possibly for $300) for Decatur, 12,000 people filled Cubs Park to watch the teams fight to a 0-0 tie. Future Pro Football Hall of Famer and former Lane Tech High School star "Fritz" Pollard was Akron's greatest asset. A phone line was kept open from the park to the Decatur Review office and the sports department yelled out every play to 2000 people in the street. The Staleys at 10-1-2 claimed the league championship. However, each club had played various games against non-league opponents and at a league meeting on April 30, 1921, the Akron (Pros) at 8-0-3 were awarded the championship.

Chicago and the APFA championship

After another summer of playing baseball for Staleys, Halas got his new recruits ready for the October, 1921 season opener. According to

14 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

This cartoon appeared in the January 1922 issue of the Staley Journal, and reflects the jealousy some of the other corn-plant workers might have exhibited the month after the Chicago Staley's won the football championship. Ma Corn is nursing a football while the play blocks spellout A E Staley Products. Later that year, Staley introduced the soybean to Illinois.

This cartoon appeared in the January 1922 issue of the Staley Journal, and reflects the jealousy some of the other corn-plant workers might have exhibited the month after the Chicago Staley's won the football championship. Ma Corn is nursing a football while the play blocks spellout A E Staley Products. Later that year, Staley introduced the soybean to Illinois.

|

the Staley Journal, "but seven of the men who wore the red jerseys during the previous season will again represent the Starchworkers as they were known all over the United States." Dressen had moved on but George "the Brute" Trafton was ready for his second of 12 seasons playing center for Halas. However, regardless of how successful the Staley football team had been on the field, they lost over $14,000 at the box office. Staley field couldn't hold very many fans and the company only charged $1.00 for admission with employees getting in for half price.

On October 6, 1921, 4 days after Decatur trounced Waukegan 35-0 at Staley Field, A.E. Staley, Sr. offered and Halas agreed to a letter of understanding. Gene Staley pledged to pay all players a salary of $25 a week and buy $3,000 worth of advertising in the team program if the team would move to Chicago and play their home games there. In return for the guaranteed $5000, the team was "to operate under the name - 'The Staley Football Club."' The players would no longer have to report to their factory jobs, but were to "secure the utmost publicity in the newspapers for the team and the Company" and to "reflect credit upon the A.E. Staley Manufacturing Company." On October 10, 1921 the Staleys defeated Rock Island 14-10 in Decatur, thus marking the last "Bears" franchise league game played in central Illinois until the Bears played all of their home games at the University of Illinois in 2002 while Soldier Field was being renovated.

Halas moved his players into the Blackwoods Apartment Hotel at 4414 Claredon Avenue and then quickly made a deal with William Veeck, Sr., president of the P.K. Wrigley-owned Chicago Cubs baseball team for use of Cubs Park as the Staleys home field. For 15 percent of the gate receipts, the now "Chicago Staleys" could use the park for Sunday games and keep the rights for all programs sold. Some form of this agreement lasted until the future Bears played their last game there in 1970.

That fall the Staleys went 9-1-1, defeating teams from New York, Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Their only defeat was 7-6 to Buffalo, N.Y., on Thanksgiving Day and that was repaid two weeks later giving Chicago a valid claim for the title. Although Decaturite Jack Mintun never gave up his factory job at Staley's, he apparently took the train to Chicago to play on weekends in 1921. On November 27 he helped the Staleys trounce Curly Lambeau and the Green Bay Packers 20-0, and during a downpour on December 11 he played the entire game at center after Trafton was injured on the initial kickoff as Chicago beat the Canton Bulldogs. As the season ended with a tie against Driscoll's Chicago Cardinals, the league president ruled the Staleys were the American Professional Football Association Champions.

In 1922 Halas no longer had any obligation to A.E. Staley. On May 2 he and business partners Edward "Dutch" Sternaman and John Leo "Paddy" Driscoll incorporated the "Chicago Bears Football Club" with the Illinois secretary of state. After all, mused Halas, football players were bigger and tougher than baseball players, therefore if the football team played in Cubs Park they needed to be "Da Bears." According to Jeff Davis' 2005 biography, Papa Bear: The Life and Legacy of George Halas, as soon as the newly named National Football League President saw Driscoll listed as a partner, "he ordered Halas and Sternaman to stop tampering with Driscoll and ruled that Paddy belonged to the [Chicago] Cardinals as player and head coach."

Halas never forgot the contributions and kindness of the Staley family business. When he learned that Staley's was observing their 50th Anniversary in 1956, he organized Staley Day on October 21 at the now named Wrigley Field. A.E. Staley, Jr. appeared on live television at half-time and introduced the remaining members of the 1920 and 1921 Staley's football teams. About 1,000 Decatur people came up for the game and Staley's paid the expenses of having the University of Illinois Marching Band perform and spell out the name "Staleys" on the field. Halas reiterated, "If it weren't for the Decatur Staleys there never would have been the Chicago Bears." Appropriately at the north entrance to Soy City stands a sign, "Welcome to DECATUR, Original Home of the Chicago Bears."

Frequent contributor Mark Sorensen teaches state and local history at Millikin University in Decatur. He currently serves as Vice President of The Illinois State Historical Society.

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 15

|