|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Walter S. Waggoner

Pike County was founded in 1823. It originally encompassed all the area of the Military Tract, which had been set aside as land for the veterans of the War of 1812. The county which was bounded on the one side by the Illinois River and on the other by the Mississippi River, originally stretched north as far as southern Wisconsin. By 1860 Pike County was much smaller in size. Its eastern boundary continued to be the Illinois River and its western the Mississippi River. Its population was thirty thousand. The original settlers largely came from the northeastern states and Missouri, Kentucky Virginia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas. Many of Pike County's residents had immigrated to Pike County from England. A settlement of former slaves was even established by Free Frank McWorter at New Philadelphia. In short, Pike County was a multicultural area that represented many different religions, races, and nationalities. President Lincoln's Springfield home was fifty miles away from Pike County, and he was well known in "Old Pike." Lincoln practiced law before the bar in Pittsfield, the county seat. While there he often visited friends like the Shastids, whom he knew from his New Salem days. In 1858 Lincoln spoke to a crowd of three thousand people from the back of a buggy at the courthouse square during the Illinois senatorial contest against Douglas. Upon the advice of his good friend and Illinois Secretary of State Ozias Mather Hatch, of Griggsville in Pike County Lincoln recruited three of his personal secretaries from Pike County Pittsfield editor John Nicolay was the first, and he recommended John Hay to Lincoln. Nicolay and Hay had been classmates and friends at school in Pittsfield. A third secretary Charles Philbrick of Griggsville, served Lincoln in the last year of the war. When the Civil War broke out in April 1861, Pike County was among the first to send volunteers to fight for the Union. Despite Lincoln's many friends and familiarity with Pike County, it had a Democratic tradition and voted against him in both presidential elections in 1860. and 1864. Nevertheless, it was conservatively estimated that at least six out of every ten county soldiers who fought for the Union were Democrats. Loyalties in the county were sharply divided along party lines. Democrats referred to Republicans as "Black Republicans," implying that they were abolitionists who wanted to make the black man equal to the white. Republicans referred to Democrats as "Copperheads," after the poisonous snake, and implied that Democrats were not loyal to the Union and were sympathetic to the South. Indeed, county Democrats were divided on the

11

prosecution of the war, and after the Civil War the editor of the Pike County Democrat wrote that it had been a problem to hold the party together. Some men openly wore butternut breast pins to show their opposition to the Republican administration and its prosecution of the war. The Bushwhackers were a third element in the county. They were a lawless group, many of whom came from Missouri. Some had served as Confederate soldiers. They committed numerous outrages from horse stealing to murder. In reality, the sentiment of Pike County was overwhelmingly pro-Union. More than one third of all of the men of the county fought in the war on the side of the Union. Members of the same family often enlisted and fought together. The Hurt family of Barry was a good example. Elisha Hurt and his sons Charles, John, and Elisha Jr. joined the Union army. A son-in-law, E. A. Crandall, enlisted as a major in the Ninety-ninth Illinois Infantry Regiment. That regiment had been organized by Col. George W. K. Bailey in only twelve days in August 1862 and was composed almost entirely of Pike County men. Attitudes towards the prosecution of the war against the South differed considerably in the county. As the war continued, partisan differences hardened. Republicans portrayed themselves as loyalists and the war party. County Democrats were split. War Democrats sided with the Republicans. A few Democrats opposed the war. The sharp differences of opinion over the war became more pronounced as the war continued. This was illustrated in the correspondence of former friends Kate Rockwell and Mrs. Hattie L. Hyde. The Rockwells were staunch Republicans, and Mr. Rockwell served in an administrative position in the Union army. In November 1862 Mrs. Hyde paid a social visit to the Rockwell home. She freely spoke her sentiments that the Constitution was being undermined by the Lincoln administration. This angered Mrs. Rockwell, who wrote to Mrs. Hyde that as she was a secessionist and a traitor, they could no longer be friends. Mrs. Hyde responded in a letter to Mrs. Rockwell that she would rather be called a secessionist than an abolitionist, and she wrote that she believed in "... the Union as it was and the Constitution as it is." Mrs. Hyde wrote other stinging letters in response to Mrs. Rockwell and took the letters to Milton Abbott, the editor of the Pike County Democrat, who was only too happy to publish them in his newspaper. Early in the war President Lincoln suspended habeas corpus. Without a writ of habeas corpus, citizens could be thrown in jail and held there without being given a trial. It was an effective way of silencing the opposition, but many Democrats questioned the constitutionality of this action. It became commonplace for federal soldiers and law officers to ride in posses through Pike County arresting those whom they suspected to be unloyal. On June 7, 1863, federal cavalry from Quincy, immediately north of Pike County, staged an early morning raid and captured three men suspected of being disloyal. The three were pulled out of their beds and led away as prisoners. George Walburn of Kinderhook, a member of the Union League and a staunch Republican, was one of the three. He was awakened from his bed by the sound of a group of men riding up to his house. Thinking they must be Bushwhackers, Walburn opened his window and fired his gun, shooting a soldier in the jaw. Walburn's house was then set ablaze. Still in his nightclothes, he was tied behind a horse and dragged to his death.

12

Many Pike County men fell on the battlefield, particularly at Vicksburg. During an assault on May 22, 1863, against Confederate fortifications at Vicksburg, as many as 102 men of the "Bloody Ninety-ninth" fell during the first ten minutes of the attack. To provide aid for the widows and children of the fallen soldiers, a large meeting was called at New Hartford on January 11,1864. No Democrats were allowed to speak at the meeting, and they were greatly offended. Hundreds signed letters of protest at being excluded from the meeting, and some Republicans supported them. The names of the protesters were published in the Pike County Democrat. Democrats eventually acted on their own and delivered piles of wood, depositing them on the Pittsfield public square for needy families. Shortly after the meeting at New Hartford, there was another at Pittsfield on February 4, 1864. Again Democratic speakers were excluded, and many Democrats stayed home. James Irwin, a leading local Republican, addressed a large crowd at the public square. Irwin claimed that the editor of the Democrat had consistently opposed Lincoln and the war. In reality, Milt H. Abbott had frequently written in support of the war, even urging deserters to return to their posts. Ironically, Irwin made a speech at the beginning of the war supporting the secession of Southern states and advocating that Washington, D.C., be given to the Confederacy. Irwin's speech so astounded the local Republican establishment that he was in their disfavor for a considerable time. That speech became a major embarrassment to him, and Abbott delighted in reminding his readers of the speech, especially after Irwin became the editor of the local Republican paper. Abbott and Irwin began personally feuding in their respective newspapers. Irwin often referred to Abbott as a Copperhead. Their feuding went well beyond politics and the conduct of the war. Each wrote about the personal scandals of the other. Each accused the other of having extramarital affairs. Abbott went so far as to publish Irwin's personal debts. Things came to a head at the rally of February 4. Irwin spoke from the back of a wagon and unleashed a vicious personal assault on Abbott. Irwin and many in the crowd were fueled by liquor. Irwin chose this opportunity to publicly settle his score with Abbott by whipping the mob into frenzy against him. Abbott's office was just across the street where the meeting occurred, on the second floor above a drug store. He was working in his office while Irwin was speaking. Then, at Irwin's suggestion, several men attacked the office of the Democrat, intent on doing Abbott personal harm and destroying his press. As a boy in Alton, Abbott had witnessed the destruction of the press and martyrdom of Elijha P. Lovejoy. Now he was in a similar situation. As the mob headed for Abbott's office, Captain Westlake, provost marshal of the area, raced up the steps barely keeping ahead of them. Westlake told the men that they would have to go in over his dead body. Two prominent local Union officers were at the meeting, and they used their influence to keep the soldiers at the meeting in line. Captain George W. Stewart of the Sixteenth Illinois Regiment called for his soldiers to fall out, saying that they had never disobeyed an order before. His soldiers relented. Col. John J. Mudd of the Second Illinois Cavalry was also home on leave in Pittsfield and used his influence to calm the crowd. The affair had been a close call for Abbott. Although he and his press were unharmed, some of the mob had made it all the way into his office before being turned back. For the rest of the day and throughout the night, a guard was placed around the office of the Democrat. Abbott had been lucky. Later that summer, across the Mississippi River in nearby Louisiana, Missouri, the Herald and the Union and Constitution were mobbed. Soldiers home on furlough and members of the Union League attacked the two newspapers there and destroyed the Herald. During the rest of the war, violence and crime were prevalent throughout Pike County Murders continued. The stealing of horses became commonplace. Abbott wrote "men talk as coolly of shooting their fellow men as if it were a matter of no more consequence than shooting a hog." Those taken to court were usually unpunished. The murderers of soldier Lewis Nelson were given a change of venue to Brown County where they were never brought

13 to trial. It became even more difficult to keep order when prisoners broke out of the county jail in Pittsfield. The jail was so badly damaged that a new one had to be built. The mail of Civil War soldiers was uncensored. Many of the Pike County soldiers wrote home that they were still being called Copperheads and were denied promotion because of politics. When the presidential election was held in November 1864, Illinois soldiers had to return home to vote. Many Pike County Democrats were denied furlough, while Republican soldiers were sent home to vote. Even the wounded were denied passage home so that able-bodied Republican soldiers could get home to vote. After the war a grand homecoming and picnic was planned for all Pike County soldiers. The homecoming was marred when Republicans insisted on having their own celebration two days in advance of the general one. As a consequence, there was no general celebration, and the county still remained divided in victory. Long after the war, divisions remained and the term "Black Republican" was used well into the twentieth century. Unlike many other central Illinois counties, Pike continued its Democratic tradition and has voted only once for a Republican presidential candidate, Ronald Reagan in 1984. The Civil War ended for Pike County and the nation, but many of the issues did not go away. Why were the civil rights of the Democratic majority ignored during the war? Should the president be given the virtual powers of a dictator in times of war, as Lincoln was during the Civil War? Does war justify the suspension of habeas corpus and other constitutional laws? Did the Democratic soldiers deserve to be called Copperheads when they were also fighting and dying for the Union? Is it ever right to generalize and smear political opponents and label them enemies? These questions are as important and relevant today as they were in the Civil War.

Thomas Best

Main Ideas

Connection with the Curriculum

Teaching Level

Materials for Each Student

Objectives for Each Student

14

5. Compare the extent and nature of political opposition in Pike County to that of their own communities and counties during the Civil War.

Opening the Lesson

Developing the Lesson

Handout 1: Analyzing a Newspaper Editorial: 15

Handout 2: Analyzing Letters:

Concluding the Lesson

Extending the Lesson

Assessing the Lesson

16

What is a Copperhead? Republican newspaper editors certainly had their own opinions. In fact, such partisan editors were bold in denouncing those newspapers they targeted as the Copperhead press. The Quincy Whig and Republican declared that Pike County Democrat editor Milton H. Abbott was a played-out, discouraged, and disgusted demagogue. The Illinois State Journal, a pro-Lincoln paper from Springfield, not only called the Pike County Democrat a one-horse Copperhead paper but charged Abbott, like all Confederate leaders, with supporting secession. However, what did those editors and writers labeled Copperheads think of themselves and their positions? The Pike County Democrat of October 29,1863, reveals Abbott's response to these written attacks by way of an editorial written by the Hon. Levi Bishop of Detroit, Michigan. We often hear it said of Democrats He's a Copperhead, he's a bitter Copperhead; shun him, cut him, don't countenance him, don't associate with him, don't trade with him, don't give him business, ruin him, crush him, for he's an inveterate [confirmed] Copperhead. Well what is a Copperhead? ...

17

After reading this editorial, answer these questions: 1. Considering the information in the first two paragraphs: How does Bishop describe Copperheads as being treated by their political enemies? What social group is blamed for inspiring such assaults? Why does Bishop believe this group turned to the use of the term Copperhead? 2. After reading the remaining portion of the editorial: What ideas and documents are said to be at the heart of the Copperhead position? What do Copperheads believe should be the goal of fighting the Civil War? What do Copperheads think of the way the Lincoln administration has conducted the war effort? How might Copperheads consider themselves to be the path of reason and compromise in bringing the Civil War to a successful conclusion?

18

The student will first want to review the paragraph in Waggoner's article that deals with background and letters of one-time friends Mrs. Kate Rockwell and Mrs. Hattie L. Hyde of Pittsfield. Next, read these informative letters and answer the questions pertaining to the correspondence exchanged between these women and subsequently published in the Pike County Democrat. Letter One: November 29, 1862 To Mrs. Hyde from Mrs. Rockwell: Mrs. Hyde: ... And in this spirit do I refuse to consider any longer as a friend of mine, a person who sympathizes with the rebels who are fighting against our glorious government, as you do; and who acknowledges that she would rather be called a Secessionist than an Abolitionist. I believe that all traitors should be put down, whether they be men or women, and I, as a loyal woman, intend to do my duty in that way I want you to understand that is only because I consider you disloyal, that I decline your friendship. When I am convinced that you think and feel as you should, I will be again ready to be your friend. Kate W. Rockwell Questions:

1. Identify the political positions and parties for which each woman was associated.

To Mrs. Rockwell from Mrs. Hyde, It was following this letter that Mrs. Hyde sent their correspondence to the Pike County Democrat with instructions for Milton Abbott, the editor, to publish their correspondence. Mrs. Rockwell: ... You know me well enough to know that our former friendship never will be renewed ... We will walk different paths. The loss of such a friend is but a passing is of but a moment's thought. I hope you will bear in mind that you are not the ruler of the universe. There is a Higher Judge of my principles than Mrs. Rockwell. I am willing to be tried in the balance with you for our Union as it was and the Constitution as it is. But, remember, if I am a traitor I have a large majority to keep me company; and your humble self will not change my opinion on the slavery question. And if you are conscientious in what you term putting down traitors (me) down, and think that it is what is called of you to do to sustain yourself as a loyal woman, and a Christian, do it by all means. For my part I can find other ways of showing my loyalty to my country besides judging my neighbors. And in your journey through life, as a person in Social Society, and a Christian, pause one moment and read the commandment: Judge not lest you be judged. H.L. Hyde Questions:

1. Upon what ideas does Mrs. Hyde rest her position about not being a traitor?

19

Letter Three: December 8,1862 Hattie Hyde wrote one more letter which was published in the paper. Mrs. Rockwell: In these times I think we should all make sacrifices, if they are needed, for our country; even to sacrifice the friendship of those whom we have loved for years, if they were to be disloyal. And in this spirit, do I refuse to consider any longer as friends of mine, persons who are traitors against our noble Constitution;—the one that Washington and our forefathers handed down to us, and under which we have lived and prospered, and received God's numerous blessings for eighty years, as no other nation had done before. Now I consider traitors those who will come out and say that they would rather have the Union broken than have it as it was. For my part, if we can have peace once more, and save valuable lives that are at this time, and still will be thrown away, I am willing to have it as it was; for I do not think that president Lincoln, or Mrs. Rockwell, has any right to molest slavery in the slave states; and if you and Mr. Rockwell think that the expression of such sentiments is treason, I have the same right to think your sentiments are treason, also; and as such shall treat them. ... I am for the Union all the time; and against the interference of any of the Constitutional rights of the people of any state, and in favor of each state regulating their own institutions in a constitutional manner... Hattie L. Hyde Questions:

1. Describe what you conclude must be Mrs. Hyde's opinions about the length and effect of the war on the nation.

20

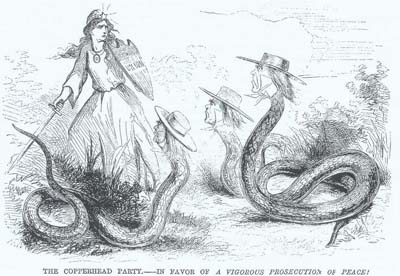

Political cartoons were another method by which people with political interests expressed themselves in the popular press. Being relatively new to newspapers due recent improvements in print technology, political cartoons primarily appeared in national publications such as Harper's Weekly, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, Southern Illustrated News, and the British periodical Punch. Cartoons were also created for the public by such well-known artists as Currier and Ives. Political cartoons typically featured a main title or caption, symbols, and caricatures to represent or satirize the people, events, or issues of interest, and dialogue offered from one or more characters featured in the cartoon. The cartoon found below appeared in Harper's Weekly, February 28,1863. Look at the cartoon and answer these questions: 1. What symbolic characters or groups are represented by the characters in the cartoon? How do these characters represent such ideas and opinions as the importance of the Union, the deception and treasonous behavior of Copperheads, and the dangerous nature of political conflict during the Civil War? 2. Would this cartoon represent the Republicans or Democrats more favorably, and why? How might a person who was labeled a Copperhead respond to the opinions and images offered in the cartoon? 3. No dialogue is presented from the characters in this cartoon. What dialogue might be added to accurately represent the opinions of original artist during the era of the Civil War? 4. How does the title of the cartoon make use of irony in the italicized section? How might you rewrite this title in your own words?

21

The Stoning to death of a School boy a letter to the Pike County Democrat, March 3, 1864. Mr. Abbott;—Permit me through your paper to inform my friends and the public of the particulars of the death of my son and the causes thereof. He attended the Newburg District School. There were some ten or a dozen boys attending the same school who seemed to have a spite at every child of Democratic parents who attended the school — branding them with being copperheads and offering repeated insults. My son, being of peaceful and quiet disposition as all my neighbors will bear me witness, he had but little to say to them. The day previous to the outrage, Thursday Feb. 18, he was in the school house. It was at noon. He heard his little brother crying and he went out and found that one of the large boys had struck him. He told the boy not to strike his little brother again; but to strike him if any one. At this the boy swore that he would bring a sling-shot and brass knuckles the next day and beat the copperhead to death. He would kill him. My son came home; told me; said he hated a fuss and that he could see no peace. I told him to go back, but say nothing to them in any way. He said he would do so. Friday morning, he went back to school in as good health as I ever saw him. After school was dismissed he started for home. This boy with some eight or ten others followed him — stoning and clubbing him for some distance; calling him all the ill-bred names they could apply to a copperhead. Samuel Hogsett, a young man of high respectability, and one whose integrity is above censure, was with my son and witnessed the whole matter. He says he saw rocks strike my son; and he, Hogsett, threw back to them. But as I requested William, my son, not to, he threw none at them. Poor boy! He came home very angry and much excited. When he retired there was a crimson flush on one cheek. Next morning he was unable to sit up, and he soon became unconscious of anything. A physician was immediately called—all was done that could be done, but he was corpse at half past 1 o'clock that night - being less than 34 hours after his brutal treatment. Thus I am bereft of a noble, kind, generous son. And for what? Because his father is a Democrat. Oh God! What is our country coming to? Must our children be thus brutally murdered, torn from the bosoms of their parents and leave them broken hearted and sorrowing-and for what? Differences in political opinion. Oh! my friends, neighbors, fellow countrymen of all parties, I call on you all, in the name of humanity, if such conduct must not be stopped. Oh! fathers consider. A darling son, in the bloom of youth, almost seventeen years old, in the best of health and hope, and the pride of his parents—their eldest son and pet—their main dependence for comfort and support. Will you not drop a tear of sympathy for his broken-hearted parents? Reuben Calbert

22 |

|

|