|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

www.ilparks.org May/June 2005 24-25 Where the Field Has Been Environmental education and interpretation have both experienced the inevitable rise and fall of trends. In the early days of environmental education, many efforts focused mainly or only on "awareness." These programs often included activities that helped participants get in touch and relate with the natural world and relied heavily on such sensory awareness activities as "hug a tree" and "blindfolded walks." Although awareness is a critical part of both environmental education and interpretation, most professionals in the environmental education field agree that a cohesive educational program is built around five components:

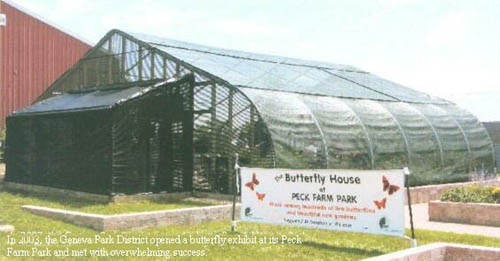

• Knowledge • Attitudes • Skills, and • Participation. After the "awareness" phase of the 1970s, environmental education moved to a focus on global environmental issues. We've all heard the saying "Think Globally, Act Locally," a popular catch phrase from the 1980's, and may have read the popular 50 Simple Things You Can Do to Save the Earth. During this time, environmental education efforts were concerned with large-scale issues. Interestingly, ecological concepts, such as acid rain, ozone depletion, loss of biodiversity, pollution, overpopulation and global warming — once thought preposterous, or, at the least, "sensitive" topics to bring up in formal education settings — are now standard learning components of many curriculums. Another trend of the 1980s was to provide fun "games" and activities for children that helped illustrate ecological concepts. In the classroom and on the nature trail, educators came to prize these sometimes imaginative, at times purely ridiculous, activities. But as we've known all along, awareness activities, global issues and games, in and of themselves, do not make an effective program. These activities are effective hands-on learning strategies only when they are part of a larger, well-structured and organized program. Today, the shift in environmental education is increasingly focused more towards the learning process itself, as opposed to making sure certain knowledge is gained. In interpretation, the trend is toward fostering meaningful connections between the resource (e.g., the site or park) and the visitor. But no matter the educational or interpretive trend, the goal remains the same - to produce ecologically literate citizens capable of making informed decisions. Two of today's trends — the rise of the butterfly house and green architecture — illustrate how planning exhibits or buildings that are specifically designed to connect with park patrons have helped accomplish that goal. Interpreting Lepidoptera - The Reasons Behind the Growing Popularity of Butterfly Houses One current interpretive trend is the growth and popularity of "Butterfly Houses" or enclosed butterfly gardens. In just over 10 years, these exhibits have opened in nearly every major metropolitan area. El Paso, Texas Zoo opened one of the earliest butterfly exhibits in May 1998. The purpose was to provide visitors with an opportunity to view concentrations of live native butterflies up-close and in person, give them basic information about butterflies and hopefully stimulate their awareness and understanding of invertebrates. It was also hoped the exhibit would boost visitor attendance at the zoo. The Natural Museum of Los Angeles County opened its first live butterfly exhibit in April 1999. The exhibit quickly became a popular extension of the museum's Insect Zoo, drawing more than 13,000 visitors in just over 4 months. 26 Illinois Parks and Recreation www.ILipra.org Were these exhibits considered successful? Arthur Evans, the Los Angeles Zoo director says that the exhibit broke down the physical barriers between visitors and insects by creating a garden-like atmosphere filled with beautiful and nonthreatening insects. The El Paso Zoo staff declared their exhibit very successful, saying "it stoked the imagination of its guests and produced 'record' zoo attendance." Here in Illinois, the story is no different. Whereas a few years ago you would have been hard pressed to find a live butterfly exhibit, the greater Chicago area now has three such exhibits in operation. These include a year-round exhibit featuring exotic and native butterflies at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum and a summer exhibit at the Brookfield Zoo. Amy Bodwell, curator of the "Butterflies" exhibit at the Brookfield Zoo, says their exhibit has been a complete success. Open since 2001, the exhibit continues to be popular with visitors of all ages. During the 2002 summer season over 118,000 visitors toured the exhibit. This equaled roughly 10 percent of all visitors that visited the zoo that year. The popularity of the exhibit hasn't waned much with age. In 2004, more than 97,000 came to see the butterflies. Bodwell says the exhibit "provides an opportunity for people to have a close encounter with a nonthreatening animal." It is also one of the few places people can closely observe animals exhibiting natural behavior. One of Bodwell's most rewarding visitor comments came from a mother who said that she and her children had visited the exhibit three years in a row. The mother said that the exhibit "changed the way my kids look at nature ... they no longer harm animals." This is most certainly a powerful statement and a significant behavior change all interpreters and educators strive to achieve. In 2003, the Geneva Park District opened a butterfly exhibit at its Peck Farm Park facility that met with overwhelming success. The district serves a population of 24,000. Prior to 2003, Peck Farm Park averaged 10,000 to 15,000 visits per year. In the first three months after the installation of the butterfly exhibit, attendance was at 17,000. However, numbers only tell part of the story. The true story is in the faces and comments of the visitors. The "ooohs and ahhhs" are endless as children closely watch the long, tubular "tongue-like" proboscis of a queen butterfly uncoil and emerge to probe deep into a flower. To learn about feeding techniques of butterflies in the classroom is one thing, but to closely observe them in action is another. "Watching butterfly behavior is perhaps the most interesting learning component of these exhibits," says Bodwell. Visitors can easily observe mating, territory defense, feeding and "puddling" behaviors throughout the exhibits, whereas, in the wild, butterflies may be too far off a path to see clearly, or may fly away when disturbed by approaching trail users, or may simply not be present on any given day. In addition, the Peck Farm Butterfly House was specifically designed to accommodate persons with disabilities or visitors unable to walk long distances. Over 200 wheelchairs rolled through the exhibit in the first summer of operation, providing a unique opportunity for individuals to view these incredible insects. One of the greatest unforeseen benefits of the butterfly house was the opportunity to begin an extensive volunteer program. In its first year of operation, the Geneva Park District was able to recruit, train and use the services of 75 adult volunteers. In fact, volunteers contributed over 1,180 hours and operated

www.ilparks.org May/June 2005 27 the entire exhibit throughout the season. A one-dollar per person recommended donation was suggested at the door and first-year donations covered all operating expenses (mainly butterflies) and volunteer supplies (shirts, name tags, etc.). This trend is more than just butterflies though. Insect and spider displays are sweeping the country and have proven to be big hits, both with the public and interpreters. Prior to the early 1990s, few institutions were operating these exhibits, notable exceptions being the Smithsonian Museum and Cincinnati Zoo. Since then, arthropod exhibits have been winning people over around the world. Both the Brookfield Zoo and Geneva Park District hired Spineless Wonders, a private company specializing in arthropod exhibit design and construction, to make their dreams a reality. Created by Kraig Anderson in 1992 while he was working on his first butterfly house for the Minnesota Zoo, Spineless Wonders has built over 15 butterfly houses and worked with over 50 institutions from across the country on various arthropod exhibits in the past 12 years. "Arthropod exhibits are growing more and more every year," says Anderson. Still, he wonders, "Where is the trend going, and when will it end?"

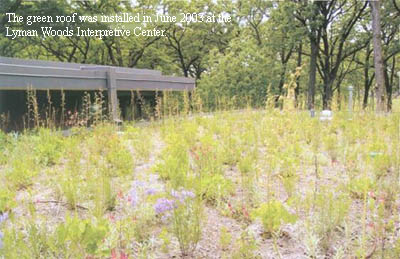

The opportunity to get up close and personal with butterflies certainly gets people interested and caring about the delicate winged creatures. More folks want to see the butterflies and agencies want to let them. After all, "if you build it, they will come," right? So it is with green buildings. Sometimes, in order to get more folks out into the natural world, you have to start in a building. The Downers Grove Park District chose to make their interpretive building a model of green thinking in Downers' last grove: Lyman Woods. The Downers Grove Park District reiterated its strong commitment to preserving open space and the natural world in 1986 by purchasing an 82-acre parcel in the middle of a highly developed suburban area. After this initial land purchase and some subsequent land easements, the district completed a master plan in 1994. The plan called for the construction of an interpretive center, but, at the time, there was not an appropriate place to site the building. Green thinking dictates you must take into consideration things such as where to build, not just how to build. To the north of the original purchase was an additional 40 acres that had been a small subdivision; the last of the houses was torn down in the late 1980s. The park district and the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County jointly purchased the degraded woodland that eventually became the ideal location for the interpretive center. Most importantly, placing the building in the "north addition" allowed the district to minimize the impact on the area's signature oak trees. The park district was also able to complete this project without disturbing traffic on a busy road as contractors agreed to auger under the street to tap into sewer and water lines during construction. From concrete floors to a green roof, the 2,800-square-foot interpretive center was designed with green thinking in mind. Included in the low-slung design are a number of environmentally sensitive materials and elements such as recycled steel supports and joists, large south-facing windows to gather winter sun, windows that open to allow fresh air to circulate, adjustable heating and cooling systems, sealed concrete floors that require less maintenance and fewer materials, porches that double as programming space, exterior and bathroom lights on timers, recycled Hardie panel siding, a compost area, rain barrels and the "green" roof. Although most people don't notice the compost or the steel supports, nearly everyone asks about the plants growing on the roof. Green roofs have gained popularity lately as Chicago's Mayor Richard Daley has retrofitted a number of city buildings with rooftop gardens. Lyman Woods Interpretive Center's green roof is not a place where you can go to eat your lunch, however. It is strictly functional. Planted with native short grass prairie plants, the roof's purpose is to reduce water runoff, cut the amount of energy used to heat and cool the building and to absorb air pollution. Special fabric layers made from recycled tires and milk jugs have been installed on the roof to allow water to drain and to stop roots from poking

28 Illinois Parks and Recreation www.ILipra.org

through. A lightweight soil mixture provides nutrients and allows plant growth. Columbine, Prairie Dropseed and Rough Blazing Star plants taking up residence on the roof may be accessible only to the squirrels and birds, but earthbound humans are still be able to enjoy the plants' benefits. A raised plantel near the center's front door replicates the roof's plantings at ground level so visitors can enjoy the beauty as well. In all the excitement to create the center, the park district never lost sight of its purpose: to educate people about the wonders of the natural world around them. Visitors will find three main themes to the exhibits:

1. Interrelationships,

The interpretive center serves as a springboard. Visitors are encouraged to spend a few minutes inside, then get acquainted with what is outside. Whatever form a nature center takes — a farmhouse, a Civilian Conservation Corps-type shelter or an environmentally innovative design — well-planned placement of concrete and steel can go a long way to open the public's eyes to the benefits of natural areas. With some well-placed education, the environmentally sensitive building trend is also taking flight. Trend Analysis If you are considering an interpretive building or exhibit, it pays (both financially and programmatically) to know "where" the field of interpretation "is" and "where is it going." Take time to become familiar with the latest research and cutting-edge efforts by park agencies across the country. Visit nature centers throughout the region to gain new ideas and, even more importantly, to learn from the mistakes of others. Take lots of pictures. Ask lots of questions. Compare construction and operational costs. Compare demographics. Compare tax bases. And most importantly, keep an eye open for the latest trend and try to incorporate it into your planning. The results will be nothing short of amazing.

Michael Kirscrimon, CPRP, is the manager of natural areas and interpretation for the Geneva Park District. He can be reached at (630) 262-8244.

Alice Eastman, CPRP, is the manager of natural resources and interpretive services for fhe Downers Grove Park District. She can be reached of (630) 963-1304.

Both serve on the IPRA Environmental Education Committee. www.ilparks.org May/June 2005 29 |

|

|