|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

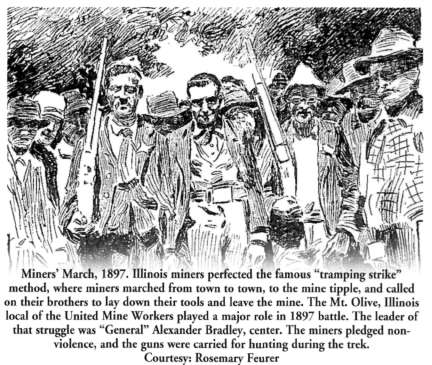

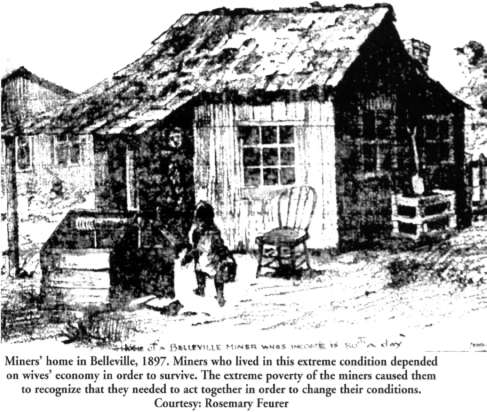

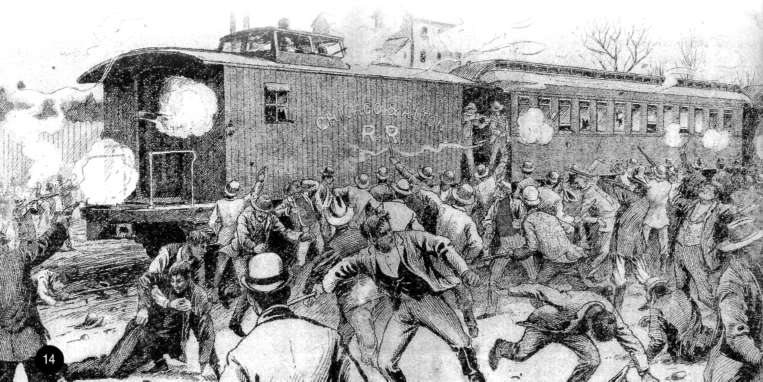

This conflict and the debates that ensued in its aftermath speak to many issues that resonate across time: a workforce made up of multiple ethnic and racial groups and the divisions that are engendered by competing identities, disagreement over who should have the right to define hours and working conditions, the weighing of labor rights versus property rights, and questions of what role government should play in intervening in conflicts between companies and workers. This essay will give some basic background to explore these issues in historical context. The Illinois mine wars of 1898-99 developed in the context of the bitter losses experienced by workers in the 1890s. Two especially notable events show why workers believed that employer power was backed by state and federal government police forces. In 1892 steelworkers in Homestead, Pennsylvania, fought hired mercenaries (Pinkerton agents) in their struggle for an eight-hour day in Andrew Carnegie's steel mills. They lost the strike when the governor sent in the state militia. The consequences of that loss were felt for the next thirty years, as hours increased from eight to twelve and conditions worsened in the steel industry. Two years later, Governor Altgeld of Illinois refused to send in the state militia to crush the famous Pullman strike of 1894. In response, President Cleveland used federal troops to defeat the strikers. But during the 1894 miners strike, Governor Altgeld sent the state militia nine times to Illinois coal towns to protect the mine operators. This showed miners that political forces held the balance of power to determine labor's fortunes. By the mid-1890s, some Illinois miners grounded in world and national politics had become fairly politicized. Miners in Illinois sought to organize unions as the means to overcome the downward spiral of lower wages, the constant chiseling on tonnage rates, and to survive in the face of the long 1890s depression. Responding to another national call for a strike in 1897, Illinois miners became increasingly unified. They perfected the famous "tramping strike" method, where miners marched from town to town, to the mine tipple, and called on their brothers to lay down their tools and leave the mine. The Mt. Olive local of the United Mine Workers played a major role in 1897, becoming the strongest in the state and preparing them for their contributions to the 1898 Virden battle. The leader of that struggle was "General" Alexander Bradley, who had participated in Coxey's Army, the band of unemployed that was a part of the waves of Populist activism in the 1890s. In 1894 they marched into Washington, D.C., demanding public works for the jobless. Bradley had started to work in a Collinsville mine at that age of nine, and, with his fellow miners, lived for the day that miners would gain enough power to bring justice for them and their impoverished families. As the example of the tramping strikers demonstrates, the social upheavals of the 1890s had a profound but dynamic effect 10 on the miners. Most importantly, they were able to surmount the multiple ethnic identities of the coalfields. Years later a union miner told a convention that "If it were not for those so called Austrians, Hunks and Bohemians" who sacrificed so much in 1897 "you would not have what you have today. Those were the men who went out and ate grasshopper soup to help win the strike." Finally, an event little noticed at the timethe refusal of Governor Tanner to send troops to Coffeen after miners used mass action to shut the mine downindicated that labor's political power in the state was growing and becoming more influential. The "tramping strikers" always sought to build community support for their struggle. Many of the small mining town's citizens realized that the poverty of the miners could reach no lower point and that the union was the last hope for a decent town and community. After months of struggle, the mine owners of the bituminous fields from Pennsylvania to Illinois agreed to a contract with the United Mine Workers Union. Almost as soon as the 1897 agreement was made, operators from three Illinois coal towns balked. The Chicago-Virden Coal Company, operating the single largest coal company in the state in Virden, Illinois, joined operators in Pana and Carterville in refusing to pay miners the amount to which they were bound by the 1897 agreement. In the spring and summer of 1898, those mine owners resolved to use African-Americans from southern states as strike breakers, a strategy that had been successfully deployed since 1877 in the Illinois coalfields. They did this in part because of the strong community support for the miners. In Pana, citizen support was so effective that mine owners admitted they could never recruit miners willing to break the strike from the Christian County area. In Virden, mine manager Fred Lukins had to build the stockade to protect the strikebreakers because he could not find a local carpenter willing to do it. At Carterville, where support for the union was weakest, operators replaced strikers in May with black miners from Tennessee, and the strikebreakers seemed impervious to the pleas of the miners to leave. In the summer, Pana and Virden operators sent recruiters to Birmingham Alabama, using deception (telling them the miners had gone to war, not that there was a strike). Some of the recruits had worked in mines, and all sought to escape their enforced poverty in the South, where black workers faced multiple obstacles to a decent life, and where the use of prison labor in the mines was widespread and kept wages constantly below poverty. By mid-September the Pana operators had returned the mines to operation with the strikebreakers, but, in the community, clashes between the strikebreakers and Illinois miners occurred regularly. Union miners gathered daily in plots to drive out the recruits, but the union leadership continually advocated peaceful persuasion as the method. Governor Tanner ordered troops to Pana after some skirmishes, but notably asked that the troops lend no assistance to strikebreaking. The three hundred Virden miners in newly organized United Mine Workers Local 693 were determined that the Pana situation would not be repeated at the Chicago-Virden Coal Company. Hundreds of their union comrades from mining communities in the central region of the state came to Virden to prevent the rogue coal operator from succeeding. Though Virden took on the appearance of an armed camp, only a segment of the miners came armed. Those from Mt. Olive and led by General Bradley, and the miners continually argued that they only sought to use peaceful persuasion to convince the strikebreakers to leave town. Among those who lined the tracks at Virden waiting for the trainloads of strike breakers were African-American union miners from Illinois, including seven from the Virden UMWA local. The UMWA's official policy on racial inclusion marked it as the most progressive affiliate of the American Federation of Labor and among the most advanced organization on the issue of race in the country. However, racial division remained a factor. In September, black organizer Richard Davis of the UMWA expressed dismay at the growing racial hostility expressed by white unionists, arguing that "no good results" would accrue  11 from seeing this as a black-white issue. "I have watched it in the past and have never known it to fail. I would advise that we organize against corporate greed." Mine manager Lukins felt confident that a fracas among the miners would prompt Governor Tanner to call in the National Guard. But, when a trainload of strikebreakers came in late September, the UMWA stopped the train and informed them that they were entering a strike. The train departed to Springfield and was met by Illinois UMWA president John Hunter. Claiming they were deceived, the recruits vowed they wanted nothing to do "with labor trouble." They marched to the governor's mansion and then to the union hall where one declared, "These miners here are all right and I wish I belonged to the union." Lukins determined that Virden miners would never again be able to commandeer a train, setting the stage for a violent confrontation. When the next trainload of strikebreakers from Birmingham pulled into East St. Louis on October 12, dozens of Thiel Detective agents boarded the train, which had three coaches of recruits and their families. The agents, armed with new Winchesters, clustered on the engines and at the entrance to every coach. When the train reached Virden, it passed the miners at the depot at forty miles an hour and headed toward the stockade. As it pulled to a stop, hundreds of miners swarmed around it. Then the carnage began. As the terrified Alabamans lay on the floors inside the car, the battle advantage was with the Thiel agents, who fired at miners from behind the stockade and from inside the trains and whose Winchesters overwhelmed the shotguns, pistols, and hunting rifles that a small portion of the miners carried.

12

But in Pana and Carterville, the struggle continued, and the racial division deepened and became even more deeply entangled with the union cause. After a major clash in November 1898, martial law was declared and the state militia called in, but the governor refused to permit union miners' homes to be searched for weapons. Some miners argued that the union should make an effort to unionize the strikebreakers, but the suggestion was left unheeded. For months, the situation was a stalemate. Pana citizens requested the removal of troops in March, and Governor Tanner agreed. A few weeks later, April 10, became known as the day of the "big trouble," when a minor skirmish escalated into armed conflict between the strikebreakers and the mine guards and the Pana unionists and their sympathizers. The militia was ordered back after more than seven were killed and twenty-eight wounded. Still, the municipal election that followed made it clear that the sympathies of the town were with the miners. The new government pledged no violence, and Tanner agreed to once again remove the troops in late June 1899. With civil authority so clearly in the hands of union sympathizers, the mine owners agreed to a settlement, which included employing only union men. Already a number of the strikebreakers had left Pana after the April 10 events, with the union paying transportation out of town. Others were given transportation to another strike in Kansas. Yet another group's transportation out of Pana was paid for by the state of Illinois, with Governor Tanner arguing that this was a cost-effective measure compared to the high cost of troops in Pana. It had cost the state $100,000 for the troops in Pana. Upon hearing that the strikebreakers would be evicted from Pana, Samuel Brush, owner of the largest mines in Carterville, proposed to bring them to Carterville, where he had operated his non-union coal mine for a year. However, the UMWA had recruited Carterville African-Americans to the UMWA, and had even set up a new town, Union City, to house those who became members and consequently were driven out of their company-owned houses. On June 30, the union recruits and strikers confronted Samuel Brush as he was traveling on a train with two carloads of Pana strikebreakers attached. One of the men confronted the train as it stopped in a town near Carterville, and ordered Brush to turn around. When Brush refused, a volley of rifle shots was fired from a wheat field. One of the wives of the African-American men died, and twenty others were wounded, as Brush and other guards on the train returned fire. They moved on to the mines to unload the strike-  13 breakers, but three hundred armed men surrounded the mines and company houses. Shooting began, but no deaths occurred in this volley. In retaliation, the African-American strikebreakers burned down Union City and scoured woods where African-American unionists had taken refuge. Finally, on July 1 troops were sent in and kept order until September 11, when Governor Tanner yielded to requests that the troops be removed. But on September 17, the unionists and strikebreakers clashed again and troops were recalled after five deaths occurred. Though non-union African-Americans continued to be the basis for keeping the union out of Samuel Brush's mines, the power of the union elsewhere in the state continued to whittle the distribution of his coal. Brush admitted defeat when in 1906 he sold out to Madison Coal Company, which pledged to employ only union miners. Through these battles, the United Mine Workers became established as an economic and political force in Illinois. With the establishment of the union, miners won an increase in their wages, an eight-hour day for most workers, the ability to challenge the chronic underpayment for coal by limiting the amount that the operator could reject, and the establishment of a union check weighman who could, as the name implies, check to be sure they were not cheated on the amount of coal they had mined. The political struggles of this era also politicized the miners in the area, and many of them became attracted to the newly organized Socialist Party. Politically, the question of what authority the state had to affirm or deny workers rights became a touchstone of political discourse in the state. The Democratic Party, which continued to hold the allegiance of many despite Governor Tanner's advocacy of workers' rights, was continually troubled by the tendency of the miners to be attracted to the socialist visions of a cooperative commonwealth based on worker and human rights. Illinois miners became known as among the most militant and radical workers in the country. Generations of union miners sought to honor the significance of Virden in securing Illinois' place in labor history. The question of racial inclusion in the UMWA was also a field of battle. Despite the radicalism of the miners, black miners continued to be excluded with the complicity of the miners union. But the "Victory at Virden," as the miners termed it, was marred by the vicious racial conflict that was also a legacy of these events. Soon after 1898, Virden and Pana became "sundown" towns, and African-American unionized miners were threatened despite the UMWA's official integrated status. Further, the racialized memory of the events was conflated with the class conflict story. In fact, in popular memory, the key efforts of African-American unionized miners in bringing about the victory were forgotten, and eventually their role was completed erased, replaced by conceptualizations of the events as a solely racial conflict. Did the racialized retelling of this story limit the radicalism that flourished in the area, or did it strengthen white workers' determination to use the power of the state to build their unions and white workers' power? While the numbers of African-American unionized miners climbed steadily in the first decade of the century, we need to know more about how those African-American unionized miners sought to open up the union to their full inclusion.  14

CURRICULUM MATERIALSby Michael K. Daugherty and Jenny L. Daugherty OverviewMain Ideas These curriculum materials for "Remember Virden!: The Coal Mine Wars of 1898-1900," include a wide-range of learning activities that will assist the student in developing a greater understanding of United States labor history. Additionally, the guide contains learning experiences that further the students' ability to analyze the validity, accuracy, and balance of historical scholarship. Through the learning activities, students will analyze the various stakeholders and points of view associated with the battle of Virden and conduct independent research on this historical event in United States history. Finally, the curriculum will assist the students in strengthening their critical and analytical skills by repeatedly asking and answering probing questions about scholarship and by offering alternative explanations through their independent research.

15

16 Developing the Lesson DeChenne provides an outline of how schema theory could be applied to labor history. The construct he provides is the pattern of union success in a historical event. The generalizations are the role of the government, the state of the industry, and the nature of public opinion. He offers those three generalizations as indicators of union success. The government's actions can greatly impact the success of unions, as it did in Virden. A fact or example from the Virden event is Governor Tanner's refusal to send in National Guard troops until after the battle and his support of the unionists' cause of not allowing strikebreakers. This greatly added to the "success" of the unionists in Virden. The state of the industry includes its economic health and competitiveness. These factors can contribute to or inhibit union success. An example from the Virden event is the Chicago-Virden Coal Company's decision to stay competitive by limiting the pay to their workers. Unable to find strikebreakers, the company decided to bring them in from the South, which in the end helped the unionists garner more community support. The third generalization DeChenne outlines is the nature of public opinion and its impact on union success. The unionists in Virden, for example, were able to rally support from the public during and after the event. Those unionists who died were labeled "martyrs." By identifying the construct, the material can be focused in a way that makes sure the construct is being taught through the facts and examples. The construct essentially drives the lesson and the activities. Although the given source, in this case the narrative section of this article, is important to the lesson, it is the construct that is central. The information explored can reach far beyond the given source. Through independent research and activities, the material is expanded on and tied together through the construct. Multiple constructs can be identified from the narrative section of this article to base and guide the lesson. More than one construct can be explored at a time or simultaneously. One construct, central to understanding history in general, could be the critical analysis of historical scholarship through questions. Another construct could be demonstrating the importance of learning/understanding labor history. From these two constructs, Feurer's article could be used in multiple ways. The text that follows will identify and explain some of the generalizations, concepts, facts, and examples and also provide activities that will narrow the constructs to a teachable format. Concluding the Lesson In equal groups, students should conduct research on one of the following topics and prepare a 10-15 minute presentation. Students should focus on the major events describing their subject and relate them to the Virden event. Describe presentation grading criteria to the students prior to assigning the activity (for example, message, clarity, accuracy, audience appeal, etc.). 1. Describe the economic and social context of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century and how this related to the events at Virden. 2. Describe the development of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) and the role of Alexander Bradley. 3. Describe industrial monopolistic capitalism and the role it played in the Virden event. 4. Describe some of the early demands of unions (8-hour day, wage increase, health and safety, etc.) and how these have carried forward into modern society. 5. Describe the nature of the technology and techniques used for coal mining in the late-nineteenth century and compare those to modern techniques. 6. Describe the role of race in the early development of unions and the role of race in coal mining at this time. 7. Describe other significant strikes that occurred at about this same time period (i.e., the Great strike of 1897, the Pullman strike, the Homestead strike, others). 8. Identify and describe the role of Mary Harris "Mother" Jones in coal mining. Potential Sources: School library, Internet; (search terms: "United States labor history," "coal mining," "unions"), University of Illinois labor studies site; www.ilir.uiuc.edu/liil. Macoupin County Web page;  17 www.rootsweb.com/ilmacoup/macoupin.htm, Illinois Labor History Society; www.kentlaw.edu/ilhs, United Mine Workers of America; www.umwa.org. Video: "Stories from the Mines," PBS Extending the Lesson To summarize this study of the Virden event, ask students to conduct an analysis of coal-mining culture and compare that culture to modern working-class culture. For example, students can be asked to compare nineteenth-century songs or poems about coal mining with contemporary songs highlighting an event or an aspect of working-class culture. For example, a song by Bruce Springsteen or Toby Keith could be compared to the themes drawn from a coal-mining song. Students should be asked to respond to questions like: 1. What was the song (or poem, or story) about? 2. What are some similar themes? 3. Why is working-class culture often expressed through music? 4. In what other ways are working-class culture expressed? Activity Resources/activity: Students can explore coal-mining culture through a variety of materials, including poems written by miners and songs about coal mining. Students could also be asked to locate two historical songs (or poems, or stories) and conduct a comparative analysis. Possible Source for songs: www.fortunecity.com/tinpan/parton/2/mines.html and www.aflcio.org/aboutaflcio/history If homework is desired, students could be asked to analyze a fictional coal-miner in a movie (perhaps, the father figure portrayed in the movie entitled, "October Sky"), on a television program, or in a book. The student could be asked to discuss how the character is represented, the history of the profession, their working-class identity, etc. Another potential homework activity could include students developing a set of questions and then conducting an interview with a local coal-miner, coal-mining union representative, or persons from related industries. Assessing the Lesson Students should develop a research or term paper. Students should be directed to analyze the Virden event across three broad categories. The instructor can ask the students to independently examine the text to find facts and examples that explain or relate to the three categories. Each of these categories can be used to explain the events of the day. Describe assignment assessment criteria to the students prior to assigning the activity (e.g., historic accuracy, research, writing style, grammar and punctuation, etc.). I.The Role of the Government Governor Tanner sent in the National Guard after the riot, and the next day Governor Tanner had the second train turned back. 2. The State of the Industry The Chicago-Virden Coal Company's inability to find strikebreakers leads to them bringing in strikebreakers from the South. Requires further research to understand why the strikers picked this issue at this time to strike and why the company was not willing to concede and bring in strikebreakers. 3. The Nature of Public Opinion The opinion of those not involved in the event or of the workers and the company. Requires further research to better gage the public's opinion.  18 Activity 1

19 Activity 1 - Continued5. What, if anything, is missing from this material? Instructor Prompt: This question allows students to explore the material beyond the text. It is important to note that most historical scholarship is non-inclusive. Writers often pick and choose the material they include, from the main actors they highlight to the examples they use to support their conclusions. Students should provide examples of other possible strikes, people, events that may be missing that might alter the way the event is understood. 6. Whose voice is missing? Instructor Prompt: This is a great chance to introduce students to the concept of historical scholarship trying to give voice to people in history. Historical voice is particularly relevant to those people in history who have been voice-less, who are not included in historical scholarship. Usually, the voice-less (women, blacks, ethnic groups) have been excluded from the primary sources. Does this article include all of the voices necessary for understanding this event? How would other voices be included? 7. What does the typical reader need to know about this time period that is missing to better understand the battle of Virden? Instructor Prompt: Students should be prompted to situate this event in the larger landscape of American history. The narrative author provides some historical context for the strike itself, but what about the political, social, and cultural landscape of the United States during this time? Prompt the students to determine what else was going on in the United States at this time. 7. How do we situate this event in the larger landscape of American history? Instructor Prompt: Students will have the opportunity to conduct research to answer this question, and it is a great way to introduce the relative importance of this one event.

20 Activity 2This activity is designed to cause students to analyze generalizations made by authors of historical texts. Ask students to answer each of the following questions by conducting additional research on the Virden event. After students have completed their research and provided responses to each of the questions, lead a class discussion using the instructor prompts outlined below. Describe activity assessment criteria to the students prior to beginning the activity (e.g., historic accuracy, research, written responses, etq.). 1. After reading the Virden text and conducting additional research on your own, would you characterize the event at Virden as a "battle" or a "riot?" Instructor Prompt: Scholarship on the event at Virden varies in what it is called. Students should first understand the importance of word choice. Then they should explore how these two words vary and what they imply. They should then choose one they believe best characterizes the event and use facts and examples to support their choice. 2. After reading the Virden text and conducting additional research on your own, do you agree that the Virden event, as a part of the struggle to organize miners, "shaped the views of a generation of workers in Illinois and across the nation," as the author stated? Instructor Prompt: One of the central arguments of the text should be examined by students. This will require further research of Illinois union history to answer completely. However, students should first determine if the text itself supports this conclusion. Then, they could list what else they would need to know to determine the accuracy of this statement. 3. After reading the Virden text and conducting additional research on your own, would you characterize the workers that died during the event as "Virden martyrs" as they were referred to by the author? Instructor Prompt: Again, students should explore the words chosen and understand that it is more than a matter of semantics. The words chosen help cast an event in a certain light. 4. Do you agree with the narrative section of the article that the "key efforts of African-American unionized miners in bringing about the victory" have been forgotten and completely erased? Use your research to support your answer. Instructor Prompt:This provides an opportunity for students to explore other sources discussing the Virden event and compare them to this article. Also, students can further explore the racial aspect of this event. 5. Do you agree with one stakeholder's assessment of the event as a "success," or would you use different terminology to describe the outcome of the event? Instructor Prompt: Students should first explore who believed the strike was a success-the author, the unionists, the company, the governor, etc. Students should also explore the ramifications of labeling the strike a success. They should then determine from later events if this event greatly influenced the company, unionism, laws, etc. This will require further research. 21 Activity 3The following activity will allow the students to conduct a fictional grand jury investigation into the Virden incident. You should assign students to groups as outlined in the following paragraphs. Students should be assigned to portray one of the teams outlined below. Describe activity assessment criteria to the students prior to assigning the activity (for example, portrayal message, historic accuracy, audience appeal, etc.). 1. Governor and his staff 2. The coal miners and their attorneys 3. The owners of the coal company and their attorneys 4. The strikebreakers 5. The grand jury 6. The judge (may be portrayed by the instructor) Present the students with the scenario (outlined below) and then convene the grand jury. After each team has presented its case, the grand jury (in collaboration with the judge) should issue a finding. This finding may include: Holding some groups over for trial, excusing some groups of guilt, issuing a pardon, paying restitution to a group, pressing charges against a particular group or groups, or other actions. Scenario: The public is demanding answers. Following the event at Virden, various local and state newspapers have printed differing accounts of the event, and the public is in an uproar. A grand jury has been convened to get to facts of the event. At the conclusion of the grand jury hearings, the grant jury/judge has the power to press charges or hold over groups for trial. As a representative of your team (above), it is your responsibility to describe what part your group played in the event and then explain why: they chose to act the way they did; explain whether they believe they were successful or not; how the event could have been averted; and whether the outcome of the event was worth the cost. Instructor Summary: Following the grand jury hearings, you may wish to summarize the event. Students will hopefully take ownership of their roles and discover the difficulty of assessing blame on a historical event. All parties have reasons and motivations for their behavior, some more or less desirable. However, it is our job as critical reviewers of historical events to understand those reasons and not necessarily to ascribe blame.

22 |

|

|