|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Lincoln's Bloomington Outside of Springfield, no community had a greater influence on the life of the prairie lawyer By Guy Fraker

One can argue that no part of the Lincoln story has been as neglected as that of the Eighth Judicial Circuit and its role in the development of the sixteenth president's intertwined legal and political careers. The Circuit at its largest consisted of fourteen counties encompassing an area of 10,000 square miles, twice the size of Connecticut. It extended from the Indiana line to the Illinois River, from Metamora to Shelbyville. It was 400 to 500 miles around on rough, badly defined roads. It took approximately eleven weeks to complete the full circle. Lincoln spent almost as much time out on the Circuit as he did in Springfield. Each county seat has its own unique Lincoln chapter, and each had men who played important roles in Lincoln's advance to the White House: Samuel Park of Lincoln; Clifton Moore and Lawrence Weldon of Clinton; Henry C. Whitney and Joseph O. Cunningham ol "the Urbana's;" William Fithian of Danville; Anthony Thornton and Samuel Moulton of Shelbyville; and Richard J. Oglesby and William Usery of Decatur, to name but a few. However, of all the towns outside of Springfield, Bloomington was arguably the most important in Lincoln's rise. He spent more time in Bloomington than any city other than the capital. Several important cases of his legal career, and important events of his political career, took place there. The voters of McLean County, of which Bloomington was the seat, carried Lincoln every time they had an opportunity. And by 1860, Bloomington was the second largest county on the Circuit. Lincoln and the railroads The Eighth Judicial Circuit informed in 1839, two years after Lincoln's admission to the bar and one year after his first court appearance in Bloomington. McLean was the only county to remain in the Circuit throughout Lincoln's career. With the exception of his two-year term in Congress, he attended almost every biannual (spring and fall) court session. Over those years, he was a fixture in Bloomington, coming to know its citizens and becoming a part of its fabric and an agent of its growth. The arrival of the railroads, the Illinois Central from the north in May of 1853 and what would become the Chicago and Alton from the south later that year, was for Bloomington, like many cities in Illinois, the most significant event in its early growth and development. Lincoln, for one, had long been involved in the promotion of the Chicago and Alton, and was an attorney for the Illinois Central. The Federal Government gave the State of Illinois substantial acreage for the purpose of constructing railroads. The state in turn conveyed this land to the Illinois Central with the provision that a percentage of the proceeds be paid to the state. Otherwise, the land itself was exempt from taxation. In 1853, McLean County attempted to levy real estate taxes against railroad lands. This was a crucial test case since other counties would have followed suit. One can speculate that this may have threatened to tax the fledgling railroads out of existence, thus substantially retarding the growth and development of the state. It was one of the most important cases in the history of the young state. Lincoln, rejecting an offer by Champaign County to represent it in a similar suit against the Illinois Central, instead argued on behalf of the railroad. McLean County was represented by Asahel Gridley of Bloomington. Eighth Circuit Judge David Davis, another Bloomington resident, ruled in favor of the county, and the case was appealed to the Supreme Court, where Lincoln was successful. He charged the railroad $5,000, astronomical when compared to Lincoln's typical fee of $10 to $100 for most other cases. The railroad refused to pay the fee, and Lincoln sued to collect in the Circuit Court of McLean County. Judge Davis entered judgment for the entire fee. Riding the circuit Lincoln's legal work in McLean County was the same as everywhere else, overwhelmingly civil as opposed to criminal. However, he did handle some significant criminal cases. For instance, Ward Hill Illinois Heritage 5

Lamon engaged him to prosecute the case of People v. Andrew Wyant, a murder case where Lincoln's opponent, the talented Bloomington lawyer Leonard Swett, successfully raised the defense of not guilty by reason of insanity. Lamon, a close friend of Lincoln's, was the State's Attorney for the entire Circuit. Originally from Danville, he had substantially aided Lincoln's career in a loose association sometimes characterized as a partnership. Lamon then moved to Bloomington in 1856 and lived there until he went to Washington with Lincoln. Lincoln was the first attorney for the Bloomington School District, forcing the city to levy taxes mandated by law to establish the public school system. The city had refused until Lincoln's intervention. When Bloomington's Jesse Fell was attempting to lure the State Normal University, now Illinois State University, to Bloomington, he sought Lincoln's legal assistance. In order to induce the state to place its first public university in McLean County, the County pledged $70,000 through a bond drafted by Lincoln. The three most important citizens in the early history of Bloomington are also three of the most important figures in the Lincoln story. The city was founded in 1830, and these three men, Asahel Cridley, Jesse Fell, and David Davis, arrived in 1831, 1832, and 1836 respectively. They had little in common except their support of, and commitment to, Abraham Lincoln. Without Davis and Fell, Lincoln probably would not have been elected president. Gridley's important role is not as well known.

Davis, a native of Maryland, came to Illinois after his widowed mother moved the family to Massachusetts, where he met his future wife, Sarah Walker. Her family, including brother-in-law Julius Rockwell, provided strong connections in the East that served Lincoln well. After attending Kenyon College, Davis settled in Bloomington where he purchased the law practice of Jesse Fell, Bloomington's first lawyer. Davis became acquainted with Lincoln on the Circuit, appearing both with and against Lincoln. In 1848, Davis was elected Circuit Judge, the only one for the entire Circuit. While on the Circuit, Davis and Lincoln often rode and boarded together, the latter a considerable benefit to Lincoln since the Judge always got the best room. Also, Davis' room was frequently the social center of those long evenings on the Circuit, and it was in that setting that Lincoln's renowned storytelling talent was fully utilized. In 1850, Davis rushed off the Circuit to Bloomington because of the death of his daughter Lucy. Lincoln accompanied the family when Davis resumed the Circuit. Davis took Sarah in his carriage and Lincoln took their only child, George, as the family dealt with their grief. When in Bloomington, Lincoln would frequently stay with David and Sarah Davis at their home, known as "Clover Lawn," located on the city's far east side. In 1872, this home was replaced by a mansion, which is today operated as the David Davis Mansion State Historic Site. Davis frequently appointed Lincoln as a judge pro tern to hear motions and similar matters when Davis was indisposed. None of the other lawyers resented the closeness of the two, a testimonial to the integrity of both. In 1854, Davis threatened to quit as Circuit Judge because Illinois Heritage 6

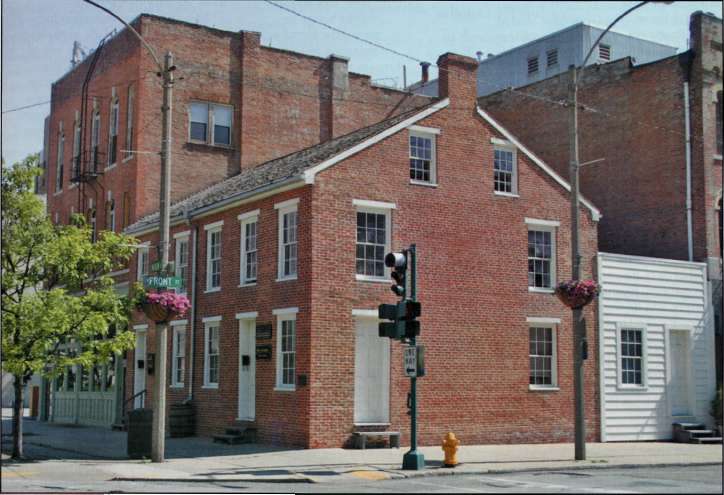

of the unwieldy size of the Circuit and its increasing volume of cases due to population growth. At Davis' request Lincoln drafted the bill reducing the size of the Circuit to eight counties. Davis was a powerful and influential figure, and his friendship with Lincoln was a factor in elevating Lincoln's status around the Circuit. Indispensable allies In May 1860 in Decatur, the young Illinois Republican Party named Lincoln its candidate for President. At Lincoln's request Davis was named an at-large delegate to the National Convention in Chicago, where Lincoln found himself an underdog candidate against the favored William H. Seward of New York. Davis went to Chicago four days before the Convention opened, set up headquarters at the Tremont Hotel, and organized the team and the tactics that stormed the Convention. His strategy was to make Lincoln the second choice of the competing delegations, and he and his team, negotiating skillfully, were victorious on the third ballot. The team he organized was made up almost entirely of Eighth Circuit Illinois lawyers, including several from Bloomington. Lincoln appointed Davis to the U.S. Supreme Court in August 1862, but only after considerable delay and vacillation. The appointment finally came after considerable urging from Davis' many supporters in central Illinois. At the request of Lincoln's son Robert, Davis was the administrator of Lincoln's estate. In 1877, Davis left the Supreme Court for the U.S. Senate. Five years earlier, he had been a presidential candidate at the Liberal Republican Party Convention. The second indispensable Bloomington resident in Lincoln's life was Jesse Fell. As an abolitionist, Fell was more radical than either Davis or Lincoln. A native of Pennsylvania and a Quaker, he came to Bloomington as a lawyer in 1832 on the advice of John Stuart, who would become Lincoln's first law partner. Fell first met Lincoln in Vandalia. It was 1835, and Fell was defending potential encroachment of McLean County's boundaries from adjacent counties. Fell's many business interests included establishing in 1836 Bloomington first newspaper, The Observer. He founded a number of central Illinois towns, including Normal, Clinton, Pontiac, Lexington, Towanda, LeRoy and El Paso.  The three contiguous Dr. Crothers Buildings at 116-118 W. Washington St. and 111-113 N. Center St. (pictured upper right in an 1860 lithograph and above in a contemporary photograph) have strong Lincoln ties. Several of his good friends, including Ward Hill Lamon and Leonard Swett, had law offices in the upper floors of the Washington St. buildings, and Lincoln delivered his "Discoveries and Inventions" lecture on the third floor of the Center St. building. Fell worked longer and harder than most others in promoting Lincoln's political career. In 1854, the year Stephen A. Douglas shepherded passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Fell invited Lincoln to come to Bloomington and hear the Democratic senator from Illinois. As Lincoln and Douglas met, Fell proposed that they have a joint discussion of the issues raised by Douglas' legislation. Douglas declined. From that time on, Fell worked tirelessly for Lincoln. He was one of the key figures of the Republican Party's 1856 organizing convention in Bloomington. He was also chosen as corresponding secretary of the party in 1857, and traveled throughout the state promoting Lincoln. In 1858, his motion endorsing Lincoln for the U.S. Senate was unanimously adopted first at the McLean County Republican Convention and then at the State Convention in Springfield, where Lincoln delivered his "House Divided Speech." During the fall campaign, Fell traveled extensively throughout the East. Some time after the discouraging defeat by Douglas, Fell ran into Illinois Heritage 7 Lincoln on Bloomington's Courthouse Square. The two men climbed the still-existing stairs to the law office of Jesse's brother Kersey. It was there that Fell first suggested Lincoln write an autobiography suitable for dissemination in the Eastern press. After a year had passed, Lincoln assented, and this short biography is one of the significant pieces of Lincoln literature. It was widely distributed, and formed the basis of numerous period sketches of Lincoln. In 1859, Fell continued as corresponding secretary. He visited a large number of the state's counties promoting Lincoln's candidacy. At the National Convention in Chicago, Fell's contact in the Pennsylvania delegation, Joseph Lewis, was influential in getting the Pennsylvanians to switch from favorite son Simon Cameron to Lincoln, a move that helped tip the scales in Lincoln's favor. Fell wrote to Lincoln in January 1861 urging the president to nominate David Davis for the U.S. Supreme Court, though he acknowledged that he and Davis had drifted apart because the Judge thought him too much of a radical. Fell remained active in Bloomington until his death in 1887. The Irascible Mr. Gridley Of the Bloomington triumvirate, the most unfamiliar name is that of Asahel Gridley. Although he is hardly a household name, even among some Lincoln scholars, Gridley played a significant role in both the history of Bloomington, and, perhaps more importantly, Lincoln's political rise. Gridley arrived in Bloomington in 1831, and he remained in the city his entire life. He served in the Blackhawk War, built the first courthouse in Bloomington, and partnered with Fell on the city's first newspaper. Gridley and Fell were very close throughout their lives, though their private and public inclinations were sometimes at odds. The kindly, generous Fell posed an interesting contrast to the oftentimes irascible, vicious, and hateful Gridley. At his funeral eulogy, Bloomington lawyer Major Packard called Gridley the "master of invective." With Lincoln as counsel, Gridley won an important Illinois Supreme Court case, giving him control of the local gas company, one of the state's first. In 1840, Gridley went bankrupt from co-signing notes for Fell. At Fell's suggestion Gridley took up the law and was very successful, appearing in more cases in McLean County for and against Lincoln than any other lawyer. He also participated in a number of Lincoln cases outside McLean County. Gridley's business interests forced him out of his practice, much of which he turned over to Lincoln. Gridley founded Bloomington's first bank, which Lincoln represented. With Lincoln as counsel, Gridley won an important Illinois Supreme Court case, giving him control of the local gas company, one of the state's first. Lincoln also represented the cantankerous Bloomington resident in a slander case brought by one of Gridley's former clients. Lincoln's defense was that if Gridley said something nasty, it was hardly a case of slander since Gridley made pejorative statements about everyone. He was Bloomington's first millionaire and built a grand mansion for $40,000 in 1859. It is said that Lincoln went into the house and asked, "Gridley, do you want everyone to hate you?" The Gridley bank and mansion, both of which were visited by Lincoln, still stand in and near downtown Bloomington. Gridley and Lincoln had a long political alliance as well. In 1840 in Springfield, in an incident that Lincoln later lived to regret, he and two other legislators jumped out of a window to avoid a quorum during a session of the state legislature. Gridley was one of the leaping lawyers. As a state senator in the early 1850s, Gridley leveraged his influence to a substantial benefit for himself and the cities that he represented. It was Gridley who persuaded the Illinois Central to move its planned line eastward so it would go through the city of Bloomington. And on occasion, Gridley assisted Lincoln's clients in passing needed legislation. Gridley was elected to the Illinois Republican Central Committee in 1856, and two years later was on the executive committee of the Republican State Convention in Springfield. Not surprisingly, he remained deeply involved with Lincoln's candidacy through the nomination in 1860. One contemporary claimed that Gridley bankrolled the Lincoln campaign to the extent of $100,000, a claim that is not otherwise documented. Gridley's loyal daughter maintained that Lincoln offered her father the ambassadorship to Russia. Gridley lived in Bloomington until his death in 1881, and Jesse Fell served as a pallbearer, as did Lincoln supporter and close friend Clifton Moore of Clinton. Gridley left no papers, business, political, or otherwise, so his role in Lincoln's life and career will never be fully known. In April 1861, Lincoln wrote that "Col. Gridley ... is my intimate political and personal friend whom I would to oblige." Leonard Swett—friend and trusted lieutenant Leonard Swett was equally important in supporting Lincoln, but not as important as the other three in the history of Bloomington. Swett, a native of Maine, came to Bloomington in 1849 after service in the Mexican War. He was immediately befriended by Lincoln and Davis as they rode the Circuit. Henry C. Whitney of Champaign County referred to Lincoln, Davis, and Swett as "the great triumvirate" of the Circuit. Swett was perhaps the finest trial lawyer on the Circuit, and argued cases with and against Lincoln. He was a trusted and loyal political operative for Lincoln, starting with Lincoln's unsuccessful 1854 U.S. Senate bid. Swett was Davis' right hand man during the 1860 Republican Convention, and then 8 IIinois Heritage traveled during the campaign solidifying Republican support throughout the East. Alter the election, he was a roving ambassador for Lincoln, meeting with future cabinet appointees, such as Seward and others. After Lincoln's inauguration, he continued playing the role of troubleshooter, undertaking as messenger several delicate errands, such as the sacking of John C. Fremont in 1862. Swett went to Washington to urge Lincoln to appoint Davis to the Supreme Court. In a touching letter, Swett told Lincoln that such an appointment would also be considered taking care of him as well. After the war Swett moved to Chicago and became one of the state's great criminal lawyers, practicing well into the 1880s. He delivered a moving and eloquent eulogy of David Davis to the Illinois State Bar Association in 1886. The wider circle Other Bloomingtonians known to Lincoln included William Orme, an attorney who partnered with Swett. Lincoln referred to Orme as "one of the most active, competent and best men in the world." Orme rose to the rank of brigadier general only to die of tuberculosis in 1866 at the age of 34. Orme married the beautiful and charming Nannie L. McCullough, whose father William was also a close friend of Lincoln's. Lie was the popular sheriff of McLean County who prevailed on Lincoln to appoint him as a colonel in the Union Army. He was 49, had one arm, and one good eye. On December 5, 1862, he was killed covering a retreat in Coffeeville, Mississippi. Lincoln's letter of condolence to Orme's daughter Fannie is one of the noted pieces of Lincoln correspondence. Another Bloomington attorney close to Lincoln was Harvey Hogg, who came to Bloomington from Tennessee in 1855 after freeing his slaves. He campaigned with Lincoln as early as the 1856 Fremont Campaign. In 1860, Hogg was elected to the state legislature only to enlist soon after in the Union Army. He was killed leading a cavalry charge in his native Tennessee in 1862. The year before, when endorsing him for service in the Union cavalry, Lincoln said that Hogg was "well known to me personally as a most reliable gentleman." Lincoln comes out swinging In addition to his personal and legal ties to Bloomington, Lincoln also made a number of important political appearances in the city. Bloomington was one of the more important locales for Lincoln's emergence as a statewide  Pictured above is the oldest known building in Bloomington. Dating to 1843, the Miller part of the Miller-Davis Buildings served as income property for businessman James T. Miller. The reconstructed white frame building to the right (the Davis part) was first used for the law offices of David Davis and Wells Colton. Illinois Heritage 9 Although Bloomington was not one of the sites for the seven Lincoln-Douglas Debates, the city was the site in July for Douglas' second speech of that campaign. leader in the Anti-Nebraska movement and the subsequent establishment of the Republican Party. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, with its repudiation of the Missouri Compromise line, threatened to introduce slavery into northern territories. This undermined the hope among anti-slavery Whigs, including Lincoln, that halting the spread of slavery would lead to its slow but ultimate demise. The political firestorm surrounding the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act famously caused Lincoln to shake off his six-year hibernation from politics, and he came out swinging. He made a series of speeches around central Illinois critical of Douglas and the principle of "Popular Sovereignty" embodied in the legislation. Although the best known of these was in Peoria on October 16, 1854 he gave a similar speech in Bloomington a month earlier, on September 12, 1854. On May 29, 1856, the disparate anti-Nebraska forces, including Whigs such as Lincoln, anti-slavery Democrats, Know Nothings, and German immigrants, convened in Bloomington at Major's Hall to organize the Republican Party in Illinois. The closing speech was given by Lincoln in what all agreed was the best speech of his career. He urged those gathered to unite in opposition to slavery, and he warned the South that leaving the Union was not an option. The speech was not transcribed, and it later became known as "The Lost Speech." Its power and eloquence placed Lincoln at the head of the Republican Party in Illinois. This speech is generally considered the second in a series of four speeches— the other three being the Peoria speech in 1854, the House Divided Speech in 1858, and the Cooper Union address in 1860—that stand as benchmarks in Lincoln's ascent to the White House. Lincoln returned to Major's Hall on two occasions that year to give similar speeches. Connecting the dots Although Bloomington was not one of the sites for the seven Lincoln-Douglas Debates, the city was the site in July for Douglas' second speech of that campaign. Lincoln was present, as he was frequently during Douglas' campaign appearances, but courteously declined to speak. The Republican candidate for U.S. Senate did return on September 3 for a major campaign appearance in Bloomington. A long procession brought Lincoln from Davis' Clover Lawn to the Courthouse Square, where 7,000 gathered to hear him speak. On April 8, 1860, six weeks after his famed Cooper Union speech in New York and six weeks before he gained the Republican nomination in Chicago, Lincoln spoke before a standing-room only crowd of some 1,200 to 1,500 in Bloomington's Phoenix Hall. This was his last appearance on the Circuit and his last political speech before the Decatur State Republican Convention on May 8. Today, Bloomington has more surviving buildings favored by Lincoln's presence —as many as nine—than any community, with the possible exception of Springfield. In addition to those discussed above, there are two buildings where Swett, Orme, Lamon, and Hogg officed, as well as the building which housed The Pantagraph in the late 1850s. Lincoln also visited the still-standing home of Rueben Benjamin, a young lawyer who later was the first dean of the law school at Illinois Wesleyan. In addition, the Miller-Davis law offices, often used by Lincoln, have been beautifully restored and rebuilt. In addition to Lincoln's frequent political appearances around the Circuit, he composed a rambling lecture entitled "Discoveries and Inventions," which he delivered at Bloomington's Center Hall on April 6, 1858. The building, along with the door through which Lincoln and his audience passed that evening, still stands. He was scheduled to deliver the same talk a year later at Phoenix Hall, another downtown Bloomington venue, but a sparse crowd led to its cancellation. In 1852, Lincoln, though not ordinarily a real estate speculator, purchased two city lots east of downtown Bloomington. He sold the two lots in 1856, though the reason for this purchase remains unknown. Lincoln's farewell Lincoln's last visit to Bloomington was on November 21, 1860 as he passed through the city on his way to Chicago to meet for the first time Hannibal Hamlin, his vice president-elect. Lincoln made a brief statement from the back of the train. News of the assassination hit Bloomington particularly hard, since residents viewed Lincoln as one of their own. The ministers on the Sunday following the assassination, April 16, called for an "Indignation Meeting" on the Courthouse Square. A crowd estimated at 5,000 gathered to mourn Lincoln's death. Fell presided over the meeting, and Gridley and Swett delivered speeches. The Pantagraph's news columns were edged in black. On May 3, 1865, Lincoln's funeral train came through Bloomington on its long deliberate passage from Washington, D.C. to Springfield. Scheduled to arrive at 3 a.m., it was two hours late. The train was met by 8,000 citizens, neighbors who came to pay their last respects to their revered, now martyred friend. Guy Fraker is a Bloomington attorney and author of "The Real Lincoln Highway: The Forgotten Lincoln Circuit Markers," which appeared in the Winter 2004 issue of Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. He has also authored an annual series for The Pantagraph on Lincoln and the central Illinois counties of McLean, Logan, Woodford, and DeWitt. 10 Illinois Heritage |Home|

|Search|

|Back to Periodicals Available|

|Table of Contents|

|Back to Illinois Heritage 2007|

|