|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

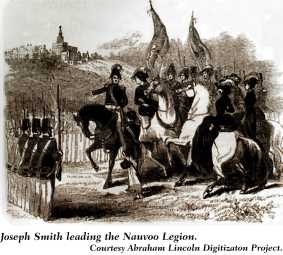

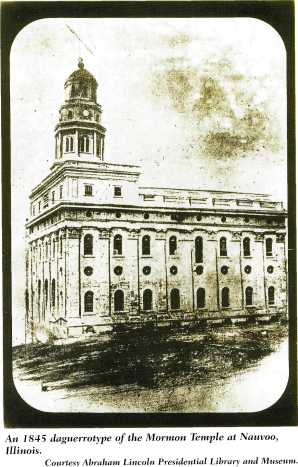

Conflict in the countryside By Susan Sessions Rugh Sometime in the spring of 1839, Ute Perkins was baptized in the chilly waters of Crooked Creek. His baptism was a harbinger of the immigration of Mormons, who numbered nearly 600 in Fountain Green Township before they were expelled in 1846. The presence of Mormons brought the rural farming community into the maelstrom of the Mormon conflict in Hancock County, which only ended after vigilante attacks removed the Mormons. What happened in Fountain Green is important because it better helps us understand the larger Mormon conflict, and how the rural farm communities were central to the escalation of hostilities. Most of what has been written about the conflict has centered on the city of Nauvoo, but places such as Fountain Green and Green Plains were the scenes of clashes between the Mormons and the old settlers.  The Mormons move in Fountain Green's involvement in the Mormon conflict began with the baptism of the township's first settler, Ute Perkins, by Joel Hills Johnson. Johnson was typical of Mormonism's early converts, most of whom were farmers or artisans from New England or New York, where the church had its beginnings. When the main body of the church moved from Kirtland, Ohio, to Missouri, Johnson spent the winter of 1838-39 in Springfield, Illinois, presiding over a detachment of the sick. As he recalled in his memoirs, in early January 1840, "the Lord showed me by revelation that I must immediately go to Carthage in Hancock County." Johnson commenced preaching in the area, and among those he convinced were the Perkins family. Ute and his wife Sarah were in their seventies when they joined the church, along with their sons Absalom and William G. Perkins, their daughters Elizabeth Welch and Nancy Vance, and grandsons Ute, Jr. and Andrew. Johnson organized the embryonic group of Mormons into the Crooked Creek Branch on April 17, 1839. By the spring of 1840, his preaching brought the size of the Crooked Creek Branch of the church to 50 persons. In late June, Joseph Smith visited the Perkins home, and the next day he spoke "with considerable liberty to a large congregation." In July 1840, Ute Perkins, two of his sons, and a local farmer sold 285 acres of land to the church to establish the town of Ramus (Latin for branch). Johnson promoted the expanding town in a letter to the Nauvoo Times and Seasons in November 1840, declaring that it was "in the midst of a beautiful and fertile country" and that the soil was "rich and productive." Lots in town could be purchased on "very reasonable terms." Johnson noted that already "quite a number of buildings, mechanical shops &c, have been erected, and many more in progress." Saw and grist mills were situated nearby, and more sites were available on the many streams. The location was also handy for Mormons migrating to Illinois from the east, because it was just 50 miles west of Beardstown on ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 6 the road from Springfield to Nauvoo. The old citizens must have been astounded at the sudden influx of Mormons into Fountain Green Township. By the summer of 1840, 52 Mormon households, or about 300 persons roughly, doubled the population of Fountain Green Township. By the spring of 1842, between 500 and 600 Mormons, about 80 families, had settled just a few miles from Fountain Green. The inhabitants of the little town of Fountain Green, who numbered about 50, were vastly outnumbered by the large number of new residents in the township. In March 1843 the state issued a charter renaming Bamus to Macedonia. A seven-member Board of Trustees assumed responsibility for keeping the streets clean, licensing taverns, and keeping the peace. The town was large enough to be divided into four wards, and the Trustees appointed officers such as constable, assessor, collector, and treasurer. Plans were made to build a grandiose Macedonian Beligious and Literary Seminary. It was to have been a two-story brick edifice located on the south side of the public square, and paid for with $1,000 of church funds. In many ways the two towns, Fountain Green and Macedonia, were more alike than different. Both were agricultural communities with town businesses servicing the local farm economy. Many of the Mormons practiced trades, and Macedonia had its share of millers, blacksmiths, tailors, and shopkeepers. Presumably, many Mormons settled there on farms, but because land titles were held through the church corporation there is scant record of land ownership in county records. The differences between the Mormons and their neighbors probably lay not so much in how they farmed, but in how they organized their society. The Macedonians had set up a typical agrarian economic structure of a village surrounded by farms locked in a network of mutual obligations. Economic ties flourished between the two towns, and the Mormon trade was initially welcomed in Fountain Green. The Mormons of Macedonia made frequent purchases at the general store of Hopkins & Tyler, from whiskey and salt by the men, to yard goods and buttons by the women. Like the people of Fountain Green, they occasionally paid off their accounts with cash, or brought in domestic products such as woven cloth. The extent of these accounts with Mormons shows that many Mormons shopped regularly in Fountain Green, and that the proprietors were willing to trust them with long-term credit. Clearly a measure of cordiality existed that allowed Mormons to mingle with the residents of Fountain Green at the country store. In spring 1839, the same time that Joel Johnson was baptizing the Perkins, Mormons fleeing the persecutions in Missouri established Nauvoo at a landing at the head of the lower rapids of the Mississippi Biver. Under the leadership of church president and prophet Joseph Smith, the Mormons swelled the population of the county (just over 3,200 in 1835) to 9,600 in 1840. By 1845 the population had more than doubled to 22,559 to become the most thickly populated county in the Military Tract. Nauvoo's population alone was said to be close to 11,000 in 1845, dwarfing Warsaw's mere 472. With the Mormons in outlying rural settlements, Mormons made up more than half the population of the county. As the hub of a wheel of settlements that radiated outward into the countryside, Nauvoo was a religious, economic, and legal center for the Mormons in Hancock County. The opposition rises The polygamy scandal intensified anti-Mormon feelings in the county. Confidence man John C. Bennett had been one of Joseph Smith's inner circle, but as he defected from the Mormon camp, he accused Smith of having multiple wives. The leaders in Nauvoo denied the charges, but historical evidence now confirms that church leaders were indeed secretly practicing polygamy. The practice of polygamy was a strong affront to the patriarchal values of the farming community, who subscribed to notions of virtue and fidelity in the domestic sphere. In an attempt to counter the Mormon majority, in 1841 local Democrats and Whigs set aside party differences to form what they called the Anti-Mormon party. Despite their unlikely political coalition, they still lacked the numbers to defeat the Mormon bloc vote. Because Mormons held the majority of the votes, political power eluded the grasp of the original settlers. Although they still possessed the right to vote, as a minority the old settlers were shut out of the county political structure. Frustrated by fruitless attempts to counter the Mormons' ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 7 legitimate political control, the old citizens went outside the law to reclaim what they saw as rightfully theirs.  On June 27, 1844, a mob of men with blackened faces surrounded the county jail in Carthage, where Joseph Smith, and his brother, Hyrum, were being held on charges of riot. The guards quickly gave way to the onrushing crowd of men, who stormed upstairs to the chamber where the Smiths and two companions attempted to defend themselves with a pistol Smith had smuggled into the jail. A warning shot pierced the door, which the mob forced open just as Joseph Smith leaped out the window. Shots from below instantly killed him, and his body fell to the ground where it was propped up against a well. His brother, Hyrum, was also murdered in the attack, but their companions escaped serious injury by hiding under the bed. The murder of the Smiths was to have been the blow that ousted the Mormons, but instead it set off a chain of violent events that shook the countryside. In the end, it was not the murder of Smith, but rural vigilantism that forced the Mormons out. While historians have concluded that the mob of men who murdered Smith represented only the most aggressive of the anti-Mormons, by the time the Mormons agreed to leave in October 1845, the countryside had become a battlefield. The Mormons won the August 1845 elections handily, with nearly 2,000 voters in Nauvoo alone. The Anti-Mormons did not even try to oppose the Mormon slate. Shut out of political power and economically threatened by the overwhelming numbers of Mormons, in 1845 anti-Mormon forces again employed illegal strategies to reclaim the county. Nauvoo, with its size and well-trained militia, was clearly impregnable. So the anti-Mormons turned on the small isolated Mormon villages that were half a day's ride from Nauvoo. The final assault Frightened by the burning of Morley's Settlement, inhabitants of Macedonia in Fountain Green Township prepared to defend themselves. British immigrant Thomas Callister remembered that first the men met "to consult what was best to be done for the mob was burning houses in the other branches turning sick women and child out to doors in a most shameful manner." They decided to post a guard at night and on September 20 Callister infiltrated a gathering at Fountain Green. "I whent and fount about 50 men Arnold ... Maclery ... swerying he would drive the Mormons out with some difficulty I got home unhurt." Two days later Mormon Bishop William G. Perkins reported to Brigham Young that there was "some little stir about our borders and the mob are training today at Fountain Green ... and we are informed that this night is set apart and appointed for the burning of this place." Perkins hastily penned a request to Young for 50 to 100 troops to arrive by evening. By midnight the next night the posse arrived from Nauvoo, fewer than half the amount requested. It was not until Ford appointed Illinois militia General John ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 8 J. Hardin, an inhabitant of Jacksonville, to take military control of the area that the violence ended. Despite some anxious moments and some saber-rattling, no one had attacked Macedonia. But the attack on rural Morley's Settlement, where 150 to 200 cabins had been burned and several men had been killed, made it obvious that decisive action was required. Citizens from several nearby counties converged in Carthage on 1 October to demand Mormon removal. Brigham Young, warned by Congressman Stephen A. Douglas and General John J. Hardin that the Mormons could no longer be protected because of the popular feeling against them, pledged to leave. At the same time, state leaders warned the vigilantes that further aggression would mean "the sympathy of the public may be forfeited" and condemned the house-burnings as "criminal" and "disgraceful." Committees were appointed in the outlying settlements to prepare for removal for an unspecified Western location; among their members was Andrew H. Perkins, formerly of Macedonia. Before the year was out much of the Mormon property in the outlying areas of the county had been sold, including land in Fountain Green Township. The main body of the Mormon church began crossing the Mississippi River in early February 1846 on their way to the Rocky Mountains. During the spring most of the Mormons packed up and moved out of the county. A few days later Macedonia was described in the Hancock Eagle as "The Deserted Village". Although just a few miles from Fountain Green, the small town of Macedonia formed its own culture which was never interleaved with the Fountain Green community. Ties of kin and commerce did not prevent animosity, but they may have forestalled violence. The inhabitants of the two communities in Fountain Green Township fought their battles on political turf, at the ballot box and in countywide organizations. When the citizens of Fountain Green began to feel that Mormon political control threatened their ideals and their property, they agitated for removal of the Mormons from the county. Erasing the Mormons In early 1846, Macedonians moved en masse with the general Mormon exodus across Iowa. They retained their branch organization while in Winter Quarters, Nebraska; then migrations to Utah dispersed the Macedonian camp. In an ironic sequel, George Washington Johnson, who had left Macedonia when a young man of 23, was called by Brigham Young in the summer of 1859 to pioneer on Uintah Springs in Sanpete County, Utah. Perhaps in hopes of recreating the verdant Illinois town of distant memory, he named his new settlement Fountain Green. Susan Sessions Rugh is an Associate Professor of history at Brigham Young University. Her article is excerpted from Chapter Two of her book, Our Common Country: Family Farming, Culture, and Community in the Nineteenth-Century Midwest (Indiana University Press, 2001). Reprinted by permission of Indiana University Press.

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 9 Sculpting Lincoln, Part 4 Lincoln At Twenty-One Bronze Statue By Fred M. Torrey (1884-1967) Story and photos by Carl Volkmann

Because of Lincoln's close association with Decatur and Macon County, Illinois Governor Dwight Green appointed a commission of prominent Decatur people to plan for an appropriate Lincoln statue. Dr. J. Walter Malone, president of Millikin University, suggested that the statue be erected on the Millikin campus. He argued that thousands of young students in their formative years would see this inspirational Lincoln statue every day. State Architect Charles Herrick Hammond chose Fred M. Torrey of Chicago to submit models. Torrey was born in Fairmont, West Virginia, on July 29, 1884. After graduating from high school, he worked as a window decorator until 1909 when he enrolled in the Art Institute of Chicago. For many years he worked as an associate of Lorado Taft. Torrey presented two models, one showing Lincoln standing and the other seated. The Decatur Public Library conducted a preference poll of Decatur citizens, and the seated figure was chosen. Torrey depicts Lincoln choosing between his axe and a book. Seated on a tree stump, his right arm rests on his right leg. He looks forward with a serious expression. His collar is open and his sleeves are rolled up. The statue was dedicated on October 24, 1948, and more than 1,500 guests witnessed the unveiling ceremony. Dr. George Stoddard, president of the University of Illinois, gave the dedicatory address and stated: "Although self-educated, Lincoln supported education, and it is therefore good to see this statue on a college campus.'' Celia Lincoln Sawyer, Lincoln's fourth cousin, unveiled the statue. Lt. Governor Hugh Cross represented the State of Illinois and reviewed Lincoln's Decatur associations. Fred Torrey and his wife were introduced during the ceremony.

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 10 Lincoln Entering Illinois Bronze Statue By Nellie Verne Walker (1874-1973)

In the early 1930s, Mrs. Julian Goodhue, state Regent of the Illinois Daughters of the American Revolution, recommended that the organization sponsor a memorial at the place where Abraham Lincoln first entered the state of Illinois. The group chose Nellie Verne Walker, a sculptor from Chicago, to design an appropriate memorial. Nellie Walker was born on December 8, 1874, in Red Oak, Iowa. Her father was a stone carver and monument maker, and he gave Nellie permission to use his tools. While still in her teens, she sculpted a bust of Abraham Lincoln, and it was exhibited at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Walker moved to Chicago in 1900 to study at the Art Institute of Chicago. She became an apprentice and studio assistant to Lorado Taft. Walker created a full-length standing bronze figure of Lincoln set against a sculptured limestone wall panel. Garbed in the heavy clothing of a young pioneer, Lincoln is holding a coonskin cap in one hand and a stick in the other hand. A scarf encircles his neck, and he is wearing boots and a jacket. The bas-relief wall includes several rectangular blocks and depicts the profiles of three adults and two children walking with an ox-driven covered wagon. A guardian angel flies above the group. The memorial stands in a thirty-two acre state park, purchased by the State of Illinois as an appropriate setting. The memorial was dedicated and presented to the state on June 14, 1938. Dr. Louis Warren, Director of the Lincoln National Life Foundation, gave the main dedicatory address. Reading from an original letter, he quoted Abraham Lincoln: "I was just a little more than twenty-one years of age when we crossed the Wabash River at Vincennes." State Historian Paul Angle accepted the memorial in the name of the State of Illinois. The memorial was rededicated on Octobers, 1988.

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 11 |Home|

|Search|

|Back to Periodicals Available|

|Table of Contents|

|Back to Illinois Heritage 2007|

|