|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

26 Illinois Parks & Recreation www.ILipra.org by LeeAnn Fisk and Sydney L. Sklar, Ph.D., CTRS Where have all the children gone? Indoors What do you remember about your favorite place to play as a child? Take a moment to go there in your memory and replay those childhood images. What did you like about that special play space? Do you remember how it looked? What did it smell like? Maybe your favorite place to play was outdoors. Perhaps it was "dirty," away from grownups, and even a little bit dangerous. If so, how did you play there? Were there mud pies and fort-building projects or games of tag and hide-and-seek? Perhaps you spent time there on your own digging for bugs or simply gazing up at the clouds. On the other hand, you may not fit the above description. Maybe your favorite place to hang out was in the relative safety of the TV room clutching the controller of your favorite video game or in the bedroom e-mailing your friends. If so, did the adults in your life encourage you to go outside to play?

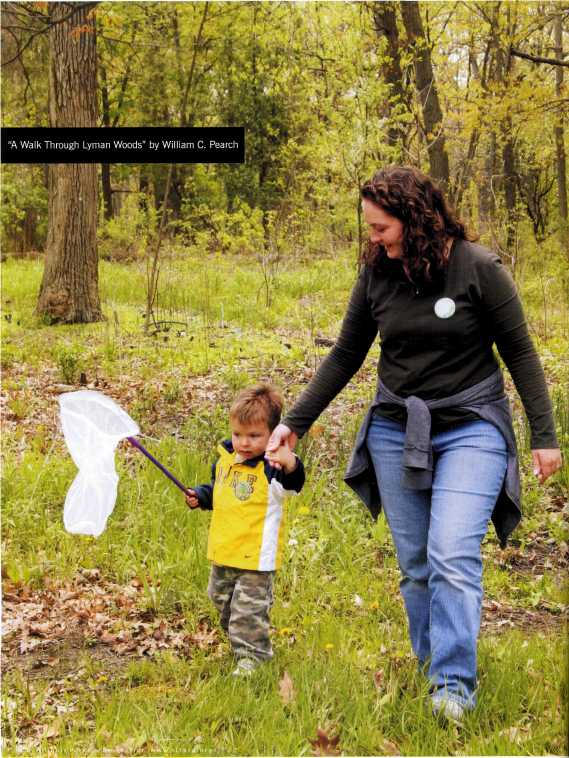

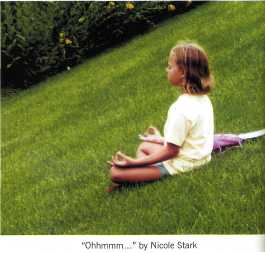

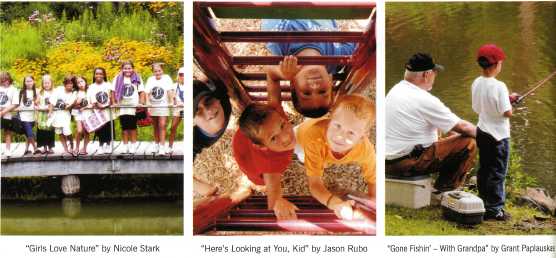

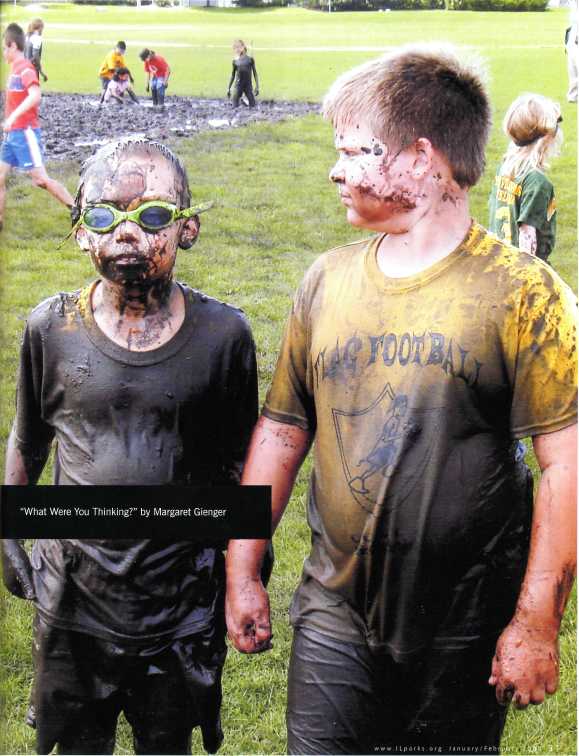

Editors Note: As part of Illinois Parks and Recreation magazine's annual Give Us your Best Shot photo contest, photographers from across Illinois contributed these images of children taking advantage of the outdoor recreation opportunities provided for them at their local park, recreation, conservation and special recreation agencies.

Why Kids Don't Play Outside Anymore Many of today's children are spending more free time indoors than in nature. School testing pressures increasingly keep kids in the classroom and off the playground. Parents are too afraid to let children out of sight for fear of abduction or injury. Busy families are overscheduled, and downtimes default to two-dimensional, electronic forms of entertainment. Children outdoors are akin to an endangered species, and a culture of fear, busyness and entertainment has contributed to the decline of outdoor play. However, it seems that, when given opportunities, encouragement, and just enough freedom, children will take to the out of doors and make it their own world to explore. Should we be concerned when they do not? Why Parents Don't Get the Kids Out the Door In his seminal book, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder, author Richard Louv brings the issue of the indoor generation to light. Louv reports the growing concern among parents, educators and physicians that children are not playing outside much anymore - not on the block, in the backyard garden or in the neighborhood park. According to Louv, children today are spending less time in direct contact with nature then they did in previous generations, and "this change in our relationship with nature has profound implications for the mental, physical and spiritual health of future generations." Numerous studies have been conducted to substantiate this concern and the impacts on child development. How can one be sure the problem is real? Time spent outdoors may be an indicator. Researcher Rhonda Clements surveyed 830 mothers between the ages of 24 and 44 years, asking them how much time their children, ages 3 to 12, spent outside compared to their own childhoods. Eighty five percent of the mothers surveyed stated that their children played less outside today then when they (the mothers) were children. One is hard pressed to identify any single culprit to the origin of the problem. Like most social problems, there are multiple factors at play. However, one issue stands out: a culture of fear. Ubiquitous news  28 Illinois Parks & Recreation www.ILipra.org outlets and public information campaigns inundate us with reasons to fear sending our children outdoors. For example, "Stranger Danger" and "Have You Seen This Child" campaigns instill fear in parents concerning child abductions. According to Louv, the number of abductions by strangers has stayed the same for two decades (roughly 100 per year), and the rate of violent crimes against young people has fallen well below the 1975 level. Another contributor is the rise in lawsuits. Litigation has taken the playground and developed it into a failsafe area - structured and safe. Yet according to Louv, "Many kids will gravitate to areas of the park that are untidy and un-manicured so that they can play on the rocks and trees or in a stream." Communities commonly place restrictions on natural areas, thus prohibiting children from free, imaginative and creative play. Louv notes, "The restrictions that prevent kids from building skateboard ramps or climbing trees is virtually criminalizing natural play." Even if they are "allowed" to play outdoors, do they have the time? In his book The Hurried Child, David Elkind cautions that we may be robbing our kids of their childhoods by expecting them to grow up too fast and become miniature adults. Children are under the pressure of "achievement overload," he warns, and "many of these young people have to keep date books because their time is so tightly scheduled." Between tutoring, soccer practice, music lessons, volunteer commitments, and homework, they just don't have any free time to play outside while the sun is still shining. The Public Health Risk of 'Nature-Deficit Disorder' So why should we be concerned that kids are spending less time playing outdoors? From a public health perspective, child development may be impaired when children lack opportunities for nature-based play. Researcher Ingunn Fjortoft conducted a nine-month study on two groups of kindergarten students in Norway. Fjortoft concluded that children allowed to play in a nature-based setting, compared to those in a traditional playground setting, showed a significant increase in their motor development. Using the European Test on Physical Fitness as a pre- and post-evaluation instrument, Fjortoft found that the children who played in a nature-based setting made significant gains in balance and coordination abilities over the control group. It may be that our embrace of modern playgrounds, in the absence of nature-based play opportunities, poses a risk to child development. As Danish landscape architect, Helle Nebelong was quoted in Ecologist: "I am convinced that standardized play equipment is dangerous. When the distance between all the rungs on the climbing net or the ladder is exactly the same, the child has no need to concentrate on where he puts his feet. This lesson cannot be carried over into all the knobbly and asymmetrical forms with which one is confronted throughout life." In his new book, Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection, Stephen Kellert reviews multiple research studies to conclude, "Play in nature, particularly during the critical period of middle childhood, appears to be an especially important time for developing the capacities for creativity, problem-solving, and emotional and intellectual development." As Fjortoft reports, "The children used shrubs for building dens and shelters and role playing like house and home, pirate's fantasy and functional] play....Free play [in nature] fostered creative play." Kellert argues that designers, developers, educators, political leaders and citizens should make changes in our modern built environments to increase children's positive contact with nature. Concerns over child obesity have also permeated our professional discourse, and the park and recreation community needs little convincing that spontaneous, active, outdoor free play can help curtail the obesity epidemic. Going beyond the issue of obesity, a 2005 article in the Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine builds a strong case for changing the discourse on getting kids outdoors. Authors Hilary Burdette and Robert Whitiker argue that efforts to get kids more physically active would be more successful if adult caregivers, parents and guardians would emphasize the concept of outdoor play as more compelling and inviting than exercise. They cite cognitive, social and emotional benefits from play in nature,  www.ILparks.org January/February 2008 29 suggesting that children will be smarter, more able to get along with others, physically healthier and emotionally happier with regular opportunities for free play out of doors. Louv states that "nature-deficit disorder" is not a true medical problem; it is the term he uses to describe alienation from nature. "By moving children indoors," he argues, "children are deprived of a full connection with the natural world." And, we may also be losing the millennium's first generation of naturalists, conservationists, preservationists and environmentalists. In his 2007 testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Interior and Environmental Subcommittee, Louv questioned, "If experiences in nature are radically reduced for future generations, where will the stewards of the earth come from?" According to Cornell researchers, children who fish, camp and spend time in the wild before the age of 11 are much more likely to grow up to be environmentally minded and committed as adults. Furthermore, research at Utah State University suggests a decrease in physical involvement of children in nature has been a primary reason undergraduate enrollments in traditional conservation and natural resource programs have fallen by nearly half since 1970. David Sobel, author of Beyond Ecophobia; Reclaiming the Heart in Nature Education suggests that teaching children about complicated and distant problems like the depletion of rainforests or the widening ozone hole produces "ecophobia," leaving students with a sense of doom and gloom about the future of the environment. Instead, Sobel argues, adults should support opportunities for children to connect with the natural world, so they may establish bonds that support later activism. The work of researcher Robert Bixler and his colleagues bolsters Sobel's argument. From a survey of 1,787 middle school and high school students, Bixler concluded that "childhood play influenced later interests in wild lands, environmental preferences, outdoor recreation activities, and occupations in outdoor environments." Taking Action A groundswell of attention to this issue has taken hold nationwide. Louv's Children and Nature Network has spearheaded the "Leave No Child Inside" campaign, a public advocacy effort to build nationwide community awareness and action. The movement has grown to gain the attention of state and federal policymakers. In March 2006, Connecticut launched a statewide No Child Left Inside initiative with a scavenger hunt in multiple state parks that attracted hundreds of families. In July 2007, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger issued a proclamation recognizing the Children's Outdoor Bill of Rights. Recently, Congressman John P. Sarbanes of Maryland and Senator Jack Reed of Rhode Island announced the introduction of a No Child Left Inside bill. This bill would provide new funding for states to develop, improve and advance environmental education standards and to train qualified teachers to teach environmental education courses and programs. How can park, recreation, conservation and special recreation professionals and board members help to leave no child inside? Start by assessing your programs and determining how to incorporate natural play within those programs. Consider your classes for preschoolers, teens, seniors and adults. Offer nature programs with structure, yet encourage free play within natural settings. Programming for this campaign cannot weigh totally on the naturalists. The move to connect children to nature can be an agency-wide effort. If you are fortunate to have a nature center and a naturalist, there is more you can do for this campaign. Look into collaborating with your school districts to bring this concept into the classrooms - or just outside the classrooms - as an ongoing experience on the school grounds, not just a once-a-year class field trip. When planning a new park or facility, consider incorporating a natural play space. Include physical environments that invite play. Features might include natural landscapes with trees, flowers and natural growth; and places and features to sit in, on, under or lean  30 Illinois Parks & Recreation www.ILipra.org

www.ILparks.org January / February 2008 31 against. The landscape can provide different levels, nooks and crannies where kids can make dens and "escape" from adults. Perhaps your agency manages natural open spaces for the community. Examine what is offered to encourage the community to visit and use that space. Offer demonstrations on maple tree sap collection. Provide seminars on wild flower and plant identification, or offer special events such as art in the park. Create a hiking club and encourage the use of nature journals to accompany the hikes. Take groups to the woods and explore the differences in trees, bark, leaves and how the branches grow. Help kids create a masterpiece with things found in nature by gluing them to canvas. Offer opportunities to dig for bugs and provide all the necessary equipment, including shovels and jars. The challenge of reconnecting children to nature can be readily addressed by the park and recreation profession. Summer camp and after-school providers have abundant opportunities to connect children with the outdoors through nature play experiences. Likewise, park and recreation professionals can creatively provide opportunities for families to explore the outdoors together. Ultimately, the profession should be concerned with providing rich outdoor recreation experiences that enable children to become their own leaders in seeking and protecting nature. Children need to learn how to enjoy nature in their leisure time so they will be independent of recreation professionals in the future. The recreation profession is positioned to have a tremendous institutional impact on the younger generation and its connection with nature. Don't miss this opportunity. Get kids outdoors. LeeAnn Fisk is a recreation supervisor at the Homewood-Flossmoor Park District and is a student at the University of St. Francis. Sydney L. Sklar, Ph.D., CTRS is an assistant professor of Recreation Administration at the University of St. Francis. What You Can Do • Organize a congressional letter writing campaign at your agency to support the Leave No Child Inside House and Senate bills. To find the contact info of your representative, go to www.house.gov/writerep. For an example of a letter to Congress and more information, go to www.naaee.org/ee-advocacy and www.naaee.org/ee-advocacy/ee-and-the-no-child-left-behind-act. • Plan natural play experiences for your preschool and after-school programs. Don't know where to start? Go to www.takeachildoutside.org for activities and ideas. • Plan activities for - and participate in - Take a Child Outside Week. Go to www.takeachildoutside.org. • Plan family-oriented outdoor activities to get adults involved and tuned in. Parents and caregivers are the key to success. • Use local natural resources for outings and nature-based activities. Visit www.chicagowilderness.org to locate natural areas near you. • Join the Children and Nature Network (www.cnaturenet.org), the founding organization of the Leave No Child Inside campaign. More Resources to Connect Children with Nature American Recreation Coalition - Read the reports of the regional and national recreation forums convened to document the importance of outdoor recreation activity: http://www.funoutdoors.com/recreationforums. Chicago Wilderness - An alliance of more than 200 public and private organizations working together to protect, restore, study and manage the natural ecosystems of the Chicago region, contribute to the conservation of global biodiversity and enrich local residents' quality of life. The organization is currently running a Leave No Child Inside campaign.- www.chicagowilderness.org. Green Hour - Proposes giving children a "green hour" every day, a time for unstructured play and the interaction with the natural world: www.greenhour.org. Earth Force -Earth Force programs offer educators innovative materials, support and training that help youth connect to their communities and address environmental issues: www.earthforce.org. Take a Child Outside Week - An international program designed to help break down obstacles that keep children from discovering the natural world: www.takeachildoutside.org. More Kids in the Woods - The U.S. Forest Service is launching a pilot program that will fund local efforts to get children outdoors: http://www.fs.fed.us/recreation/programs/woods/index.shtml. Life's Better Outside - A Texas public awareness push to promote outdoor recreation and exploration: http://lifesbetteroutside.tpwd.state.tx.us/. No Child Left Inside - Connecticut's statewide campaign to bring children, families and visitors to the state's parks, forests and waterways: http://www.nochildleftinside.org/. 32 Illinois Parks & Recreation www.ILipra.org |Home|

|Search|

|Back to Periodicals Available|

|Table of Contents|

|Back to Illinois Parks & Recreation 2008|

|