|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

B • E • T • W • E • E • N

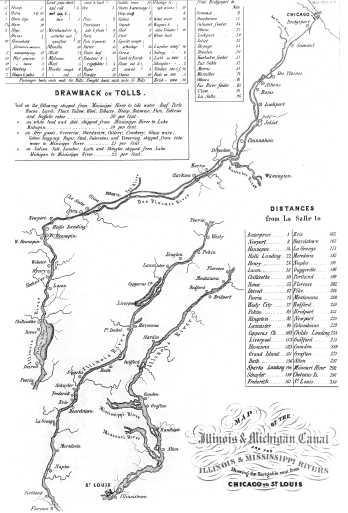

The Illinois and Michigan Canal: The Long Route Between the Waters Perry R. Duis The Buffalo Whig & Journal of June 11, 1835, was almost tired of describing the "ever-flooding and apparently boundless emigration" passing through town: For the last two months, it has been well-known to the publick [sic], that, nearly a million acres of fertile public lands were to be sold at auction in Chicago, during the present month; and these lands lie on the route of the great canal from Chicago to the Illinois river, and are supposed to possess uncommon advantages for investments. Accordingly, for weeks we have had numerous daily arrivals so from all quarters of the Union, and all are driving to the great point of attraction, 'the land sale at Chicago!' Our hotels have been crowded out of all manner of convenience; our streets have been a continual fair; our bookstores have been ransacked until not a map of Chicago, or a sketch of the great west could be found. . . The fact that a land sale six hundred miles away could generate so much interest is also an indication of an important characteristic of the history of the Illinois and Michigan Canal: its central role in creating a far-flung transportation corridor. A corridor is a linear concentration of activities, usually distinct from the areas outside of it. Every form of ground transportation—roads, canals, railroads, and highways—creates ribbons of development. Corridors such as the I and M inhabit our imagination on two levels. First, there was the grander continental vision, the 11

that river would become a giant island. This had been inherent in Father Marquette's initial suggestion that a short ditch across the Chicago Portage would help to unite the northern and southern French possession in North America. The vision was later repeated in the 1816 establishment of an "Indian Boundary Line" that protected access to the route of the future canal. Many Easterners thought that their investment in the Erie Canal, which was completed in 1825, would not generate its maximum profit until the I and M completed the route between the Atlantic and the Mississippi. Only then would New York manufacturers be able to obtain both raw materials and markets in which they could sell their finished products. Once the western canal did open, it facilitated a vast exchange of nature. The baggage of the settlers on their way to new farms contained the seeds from the East and from Europe that would sprout on the frontier; and northwoods lumber ended up in new houses on the tree-barren prairie. Those boats passed ones containing Illinois grain that quickly found its way to New York tables, as well as vast quantities of western grass seed that would be sown in New York State. The canal also made it possible for farm families to visit Chicago and for frontier general stores to obtain Eastern fancy goods at wholesale stores in the city. But there was also a more localized level of significance in the history of the I and M as a corridor. When it ran through your town, "the ditch" had a different set of meanings that were not only more parochial in geographic scope, but also more directly affected the lives of the people living in the string of towns that grew up along its banks. For instance, from the beginning, the construction process created a corridor of technology. Although seemingly crude by today's standards, the methods used to survey a route, plat towns, and then cut through seventy-five miles—much of it limestone—at a precise grade, represented a perfection of the excavation and building techniques that had been employed for decades in the East. And the engineering talent that directed the diggers and designed the locks and aqueducts were veterans who brought with them the experience of working on earlier canals. Many would later use the same earth-moving techniques to build railway right-of-ways. The construction process also helped to excite an interest in technology among Chicagoans. Ira Miltimore and the Mechanics Institute, an early group interested in promoting engineering, reported on the advantages and problems of shallow-and deep-cut proposals and water pumps. The need to lift grain into storage facilities introduced the technology of elevators and encouraged the adoption of steam power in the communities along the way. The coal that had been discovered in the La Salle region in late 1840s not only provided a new fuel source for those engines, but because it was of the sulfurous bituminous variety, it could also be baked to yield the "lighting gas" that was introduced in Chicago in 1850.

This technological revolution, in turn, encouraged local industry in the towns that grew up along the route. Know-how in the form of skilled workers traveled the boats, which also carried in raw materials and hauled away finished product. In the decades to come, towns along the canal would process metals, manufacture clocks and telegraphic instruments, and brew beer. The earth would also yield clay for potteries and the "Athens marble" that survives today on the front of countless nineteenth-century Chicago buildings. By the time the Rock Island Railroad was completed in 1854, the canal towns were already receptive to new technologies that formed the basis of an industrial corridor. Like any transportation corridor, the canal also introduced problems along its way. First, there were the thousands of construction 12 workers who might best be described as sojourners, those who become temporary residents who tend not to put down permanent roots and who remain somewhat alienated from their surroundings. Prejudice against the Irish Catholic canal diggers inflated the native-born Americans' fear of the immigrants' occasional disorder. To those outside of it, the construction corridor became a socially isolated swath of fetid constructions camps and grog shops; it was easy to forget that it was also a linear concentration of back-breaking work and construction-related injuries that separated canal workers from the other residents. By contrast, town-building attracted emigrants who were drawn heavily from upstate New York; their influence can be seen in such town names as Utica and Seneca. After the canal opened, it became a corridor of strangers, and the press occasionally reported the transit of criminals whose ease of travel provided the anonymity they needed to carry out burglaries, pass counterfeit bills, and perpetrate other misdeeds. Then there was the matter of disease. How epidemics were spread remained a terrifying mystery before our present "germ theory" became widely accepted in the 1880s. Periodic pestilence came with warm weather, killed quickly with gruesome symptoms, then disappeared when temperatures fell. Ironically, the seeming purity of the virgin frontier contained a series of killers — mosquitoes (malaria), fleas ("prairie itch") and cholera, which the northeast part of the state feared the most. Although each outbreak of the disease had traveled for many months along international trade routes from origin points in Asia, most people comprehended only local outbreaks. It had first appeared in 1832 when it traveled from Detroit to Fort Dearborn with General Winfield Scott, who was on his way to battle Chief Black Hawk. With nearly half of his force dead or dying, Scott's force depopulated the hamlet of Chicago before tramping west. Cholera became associated with "the ditch" in 1838, when what was probably malaria was popularly labeled "canal fever" or "canal cholera" and associated in the public mind with the squalid living conditions of the Irish construction crews. Genuine cholera returned in 1849 on trading ships landing at New York and New Orleans. Although commerce with the East posed some disease threat, the unexpected problem arising from Chicago's new trade connection with the Lower Mississippi forced local officials to make a tough decision. Telegraphic messages, along with information brought by the passengers and crews of ships, indicated that the disease infestations were gradually moving up the Mississippi. By March and early April the disease had made an appearance in towns along the Illinois River as well, creating a corridor of pestilence. Some Chicagoans demanded the immediate closing of the canal at La Salle to keep the city safe. Others argued that diseased persons would make their way by foot anyway and that a canal quarantine would plunge the Chicago economy into a deep economic depression. The optimistic, burgeoning city was faced with a sad inevitability. City officials allowed the I and M to remain open, and the predictions came true. On April 29,1849, the canal boat John Drew docked with a load of immigrants who had entered the country at New Orleans. Captain John Pendleton and several passengers were clearly ill, and when they fanned out into the city, they spread the disease. City officials—who remained divided over whether to blame the filthy sanitary conditions, the victims' personal cleanliness and intemperance, or the arrival of infected outsiders—ordered the streets cleansed and covered with a hundred barrels of lime. Even then, by the time the epidemic had run its course in late October it had killed 678 people, roughly 2.7 per cent of the population. The next season saw cholera return on a lesser scale, and finally in June 1851 the Chicago Board of Health sent an officer to inspect canal boats at La Salle and quarantine any with disease. Smaller outbreaks took place for the next two years, but they came from ship and rail arrivals from New York. The canal corridor had shed its aura of fear.

The regularity of canal boat schedules created a temporal rhythm in the towns that were served, as well as providing employment and payrolls. The canal corridor also became a major conduit for information and opinion of many kinds. Political candidates, teachers, editors, and other opinion-makers had easier access to "the interior," as Chicagoans often called downstate districts. Southern tourists and authors penning travelers' accounts of the West formed impressions of whatever they could see as they floated by at five miles an hour. Postal service also adapted to the corridor. The boats that began carrying the mail arriving from Chicago provided corridor residents easier communication with relatives and business contacts back in the East. The carriers also encountered complaints about mail service. Residents in Summit, for instance, were upset to learn that bulk mail was loaded onto southbound boats at Bridgeport, sorted en route to La Salle, and then placed on northbound boats before being dropped of at individual towns. The arrangement meant that customers closest to Chicago, who had assumed that they would enjoy fast service, became frustrated when they received newspapers and other mail more than a day after it had left the city. 13

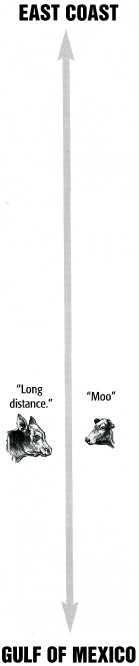

As time passed, however, the canal came to be considered a corridor of useful obsolescence. Still functioning as a mover of products, it lost its passenger-carrying function to the Rock Island railroad after only six years, and by 1860 shipping interests and politicians were advocating plans to widen and deepen it to accommodate larger lake and river vessels. For a time during the Civil War, advocates argued that the free movement of naval ships from the Mississippi to the lakes would provide military protection in the event that Great Britain sided with the Confederacy. But even after the canal itself was replaced by more modern waterways, the corridor of development that it created remained intact. Finally, the canal also reminds us that history is the story of change over time, and history is all about time and the way that things evolve at different paces. Like highways and railroads, the Illinois and Michigan Canal remains fixed in place, a corridor of historic artifacts that instruct us that there was another age. And we are also reminded of the interplay of time and permanence: that the creation of such a permanent artifact so many years ago required the labor of thousands of sojourners who stayed around awhile. Finally, as a transportation corridor, the canal was built to serve mobile people and things that just passed through. CURRICULUM MATERIALS Overview Main Ideas Today the Illinois and Michigan Canal is recognized for its historic importance as the waterway that connected Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River. This 96-mile-long national park, contained within the Illinois counties of Cook, DuPage, Will, Grundy and La Salle, encompasses a geographic area of about 322,000 acres. In 1984, the region was designated as the nation's first National Heritage Corridor. Due to ongoing, cooperative partnerships between federal, state and local governments, private industry and interest groups, the canal area has been preserved and is available for public use and industrial activity. The Illinois and Michigan Canal was the final all-water route linking the East Coast and the Gulf of Mexico. The Illinois and Michigan Canal was built between 1836 and 1848. When construction began, northeastern Illinois was a sparsely settled wilderness which, in the span of a few years, grew to become prosperous and populated. As a transportation corridor, the I & M Canal brought manufactured goods and materials to the area, as well as people. This in turn created more industry, which encouraged more people to settle along its banks. Connection with the Curriculum Teaching Level Materials for Each Student

Objectives for Each Student

14

Opening the Lesson Read aloud the first paragraph of the narrative, which includes the quote from the Buffalo Whig & Journal of June 11,1835 Give students the "What's My Line?" handout and ask them to answer the following questions: What do you think caused this "boundless emigration? Give students time to answer the questions. After a few minutes, discuss what the students think. Draw on the board or use an overhead of the "What's My Line?" handout to write down their ideas. Inform the students that they will be reading the rest of the article, "A Corridor of Time", which tells about the construction of the Illinois & Michigan Canal and the effect this corridor of transportation had not only on the Midwest but on the nation. Give students class time to read the article, or assign it to be read prior to Activity 1.

Developing the Lesson Activity 1 Discuss with students the information in the "Main Ideas" section concerning the Illinois and Michigan Canal area today. Distribute the Activity 1 worksheet, "A Corridor of Time," to each student. Have students read the definition of corridor. Tell them that they are to reread the article and see if they can find two or three connections to the corridors within the article. To help students with reading difficulties, they may do this activity in pairs. Each student should complete his or her own Activity 1 worksheet to turn in. Ask students to think about the historical significance of each of their connections. Post five pieces of large chart paper in various locations in the room. On each chart write one of the corridors listed on the Activity 1 worksheet. After students have been given time to complete the worksheet, arrange the class into five small groups. Assign one of the charts to 15

each group. Within their group, students will discuss the connections they have made on their worksheets to their assigned corridor. As a group they will pick three connections to write on the chart paper. Reconvene the class as a whole. Have one person from each small group act as a speaker to relate the group's connections to their particular corridor. Discuss the historical significance of each connection. Activity 2 Distribute the Activity 2 worksheet, "The Illinois & Michigan Canal: + or -," to each student. Read aloud the directions and the question that the students are expected to answer in a persuasive essay. Through the use of an LCD projector/computer and Internet connection, discuss the contents of each Web site (which should be previewed prior to the activity). If there is the availability of a computer lab, students could browse the Web sites as each is discussed. Students should be given enough time to complete their Internet search and to write notes to develop their persuasive essay ideas. Encourage students to also use information from the article to support their essays. When essays are completed, take a show of hands tally of whether students wrote a persuasive essay about the positive or the negative aspects of building the Illinois & Michigan Canal. Have students read their essays aloud. Through an open debate format, discuss each student's essay after it is read. List the points discussed on the board. When all student essays have been shared, retake the show of hands tally and see if anyone has a changed opinion. Activity 3 Distribute the Activity 3 worksheet, "Are We There Yet?" Discuss with students the fact that the area along the Illinois and Michigan Canal has become a recreation area today. A 60-mile biking and hiking trail has been developed by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. In addition, there are many volunteer opportunities and Adopt-A-Trail organizations that work to maintain the canal area. There is even an I and M Canal license plate. Tell students that they are going to make a brochure advertising the I and M Canal. Students may use information from the Web sites they reviewed in Activity 2 to include the history of the I and M Canal in their brochure. Distribute the "Are We There Yet?" rubric. Discuss with students the contents of each section of the rubric and what should be included in the brochure to get a rate of 4. Students should be given time in class to work on their brochures. Concluding the Lesson The Illinois and Michigan Canal was 160 years old on August 24, 2008. Its historical significance is evident in the fact that people and communities continue to benefit from its existence. Students should be encouraged to visit this state and national landmark to further connect the past to the present and ensure its survival for the future.

Extending the Lesson Prairie Tides: The Building of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, funded by the Canal Corridor Association, is an excellent video resource. The historical review to the video guide states that "Prairie Tides is the story of the building of the Illinois and Michigan Canal and embraces all the great themes of American History. It is a video that tells the story of the lives and dreams of hard-working people who built that canal and in turn, the country. Students will recognize names familiar to American history like Louis Jolliet and Abraham Lincoln. It is all here, the story of an immigrant odyssey that grew a region and replaced the Native American culture on the prairie." A copy of the video guide can be found at http://www.lewisu.edu/neh/Lesson_h2.doc. Assessing the Lesson All the activities may be assessed as the teacher wishes. The "Corridor in Time" worksheet should include general connections within the article under each subheading. The "Illinois and Michigan Canal: + or -"essay could be assessed using the Illinois State Achievement Test rubric for a persuasive essay. Use of the "Are We There Yet?" rubric to assess the "Are We There Yet?" brochure is highly encouraged. 16 Handout – What's My Line? Read the following excerpt. Then answer the questions with your ideas as to what historical event is referred to. The Buffalo Whig & Journal of June 11,1835 was almost tired of describing the "ever-flooding and apparently boundless emigration" passing through town: For the last two months, it has been well-known to the publick [sic], that, nearly a million acres of fertile public lands were to be sold at auction in Chicago, during the present month; and these lands lie on the route of the great canal from Chicago to the Illinois river, and are supposed to possess uncommon advantages for investments. Accordingly, for weeks we have had numerous daily arrivals so from all quarters of the Union, and all are driving to the great point of attraction, 'the land sale at Chicago!' Our hotels have been crowded out of all manner of convenience; our streets have been a continual fair; our bookstores have been ransacked until not a map of Chicago, or a sketch of the great west could be found. . .

What was this "boundless emigration"? What "great canal" is referenced? What sort of "investments" would be possible? 17 Activity 1 – A Corridor of Time The Illinois and Michigan Canal area is currently known as a National Heritage Corridor. From our reading of the narrative we learned that "a corridor is a linear concentration of activities, usually distinct from the areas outside of it." Use information from the narrative to give two to three connections associated with the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Be prepared to discuss the historical significance of each of your connections.

A corridor of transportation: A corridor of strangers: A corridor of technology: A corridor of information and opinion: A corridor of historical artifacts: 18 Activity 2 – The Illinois and Michigan Canal: + or - Write a persuasive essay to answer this question: Was the Illinois and Michigan Canal an overall gain or loss for Illinois? Include information from the previous article, the Web sites below, and your own ideas. Websites: Department of Natural Resources: I and M Canal National Heritage Corridor http://dnr.state.il.us/lands/landmgt/parks/i&m/main.htm Illinois State Archives: Historical Background section http://www.sos.state.il.us/departments/archives/i&mpack/i&mintro.html

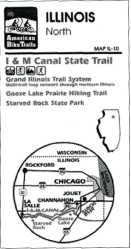

Chicago Public Library: Be sure to click on the map. http://www.chipublib.org/digital/sewers/canal.html Lewis University Canal and Regional History Special Collection http://www.lewisu.edu/imcanal/index-imcanal.htm Canal Corridor Association http://www.canalcor.org/ Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illinois_and_Michigan_Canal 19 Activity 3 – Where Do We Go From Here? The I and M Canal area is used as a recreation area today. Your assignment is to make a brochure advertising the history of the I and M Canal and encouraging people to visit the area today. Your brochure will be graded using the attached rubric. Here are two examples of brochures and the websites where they can be found: This brochure is published by American Bike Trails.

Where to bike throughout the I and M Corridor http://www.trailresources.com/b032.html

This brochure is also published by American Bike Trails Illinois Trail Map: I and M Canal State Trail http://www.trailresources.com/il10.html 20

Activity 3 – Where Do We Go From Here? Making A Brochure : Are We There Yet? Student Name:_______________________________________

21 |

|

|