BY DOUGLAS KANE

Kane holds the Ph.D. degree in public

finance from the University of Illinois-

After serving on the staffs of both the

legislature and the governor, he was elected

to the House of Representatives from

Montgomery and Sangamon counties

last fall.

Effect of inflation on state finances; a variety of elements are involved

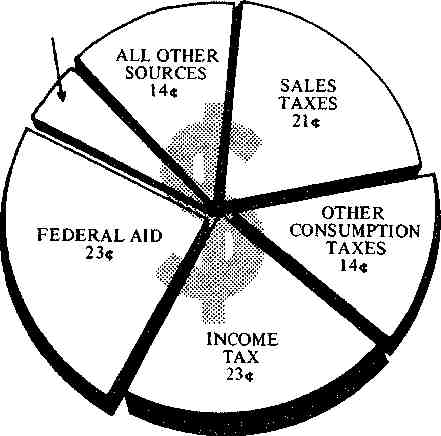

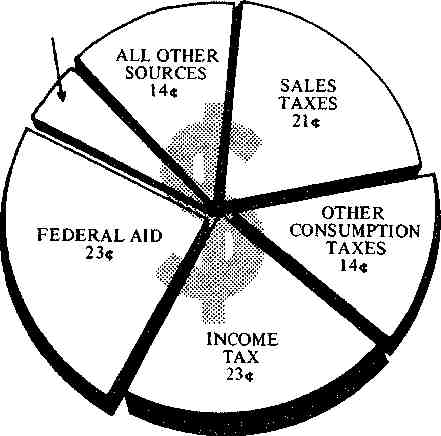

THE STA TE'S DOLLAR.

Where It Comes From

Based on budget for FY 1975

BOND PROCEEDS 5¢

|

GOVERNMENTS like people have to

cope with inflation.

School districts that heat their

buildings with fuel oil and run their

buses on gasoline have had to pay the

doubled and tripled costs just like

everyone else. Township road programs

have been scuttled as the price of road

oil has jumped from 17 cents a gallon to

46 cents a gallon in a year's time.

Mental health institutions and prisons have

had to pay the increased costs for food

just like the housewife in the

supermarket. Teachers, administrators,

firemen, policemen, professors, prison

guards, game wardens, ward workers in

institutions, tax collectors, highway

maintenance men, secretaries, clerks

and the myriad others paid with public

money also face higher prices and, like

everyone else who works for a living,

exert pressure, sometimes subtle,

sometimes blatant, for larger pay

checks.

What does inflation do to state and

local government finances? Do the

pressures of increased costs make tax

increases inevitable? Or do revenues

keep pace leaving government budgets

relatively unaffected? Do some kinds of

governments gain by inflation, just like

some businesses gain, and others lose?

Where in the Illinois public sector does

inflation hurt the most? Where is the

stress most likely to appear?

Before looking at state finances and

then moving to the local scene, it may

be well to take a brief look at the

dimensions of the inflation that has

rocked the economy. The recent steep

rise in prices came near the beginning

of 1973 following two years of price

increases at a 3 to 5 per cent annual rate.

In 1973 inflation ran between 8 and 10

per cent, rising in 1974 to the 12 to 14

per cent level. The commodities on

which prices rose the fastest were foods

and petroleum products.

Economic theory would indicate that

inflation by itself will not directly hurt

general state finances. Revenues,

particularly from the sales and income

taxes, should keep pace with increased

costs. Highway finances are another

matter, however, and theory would

indicate that severe problems could

develop. But the state does not stand

alone. It is not fiscally independent. It

receives substantial money from the

federal government and, in turn,

contributes even more money to local

governments around the state. If

inflation results in federal cutbacks in grants

or pressure at the local level for

increased state aid or a combination of

the two, then the state could be caught

in a squeeze between decreased

revenues and increased demands.

Sales, income tax yields rise

The revenue side of the picture comes

first. Do revenues keep pace with inflation?

The state's general, fund is supported

primarily by the sales tax and the individual and corporate income taxes. In

fiscal 1974 these three taxes accounted

for 78 per cent of all genera! revenue.

The sales and income taxes have kept

pace with inflation. The sales tax is

levied on price, and as prices rise,

revenues rise along with them. In an inflationary spiral, wages and profits rise

along with prices and income tax

revenues.

Almost 50 per cent of the Illinois

sales tax comes from the sale of food,

automobiles and automotive products

including gasoline. As these are the

areas that led the inflation, one would

expect sales tax revenue increases to

have exceeded the rate of inflation, at

least until the end of 1974 when car

sales slumped badly. This is approximately what happened. Fiscal

1973 sales tax revenues exceeded fiscal

|

March 1975/Illinois Issues/67

|

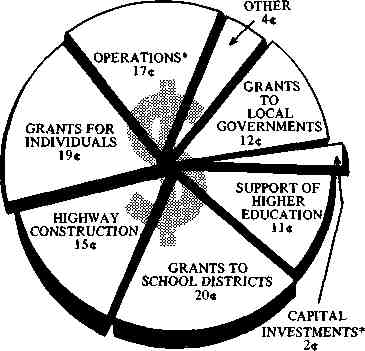

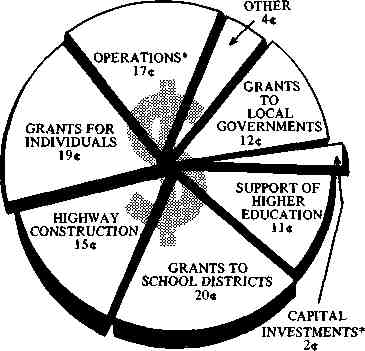

THE STATE'S DOLLAR:

Where It Goes

Based on budget for FY 1975

*Excluding higher education

|

1972 revenues by 8.2 per cent. Fiscal

1974 revenues climbed another 15.4 per

cent, while revenues for the first several

months of fiscal 1975 were up better

than 12 per cent.

Income tax revenues were up 10.6 per

cent in fiscal 1973 over 1972, increased

another 13.8 per cent in fiscal 1974, and

rose again by more than 12 per cent in

the first few months of fiscal 1975.

Revenues from taxes based on

quantities rather than prices, like the

cigarette and liquor taxes, have not kept

pace with inflation, and collections in

fiscal 1975 are barely higher than

collections in fiscal 1972. Inflation, in

fact, may have a negative effect on

yields from such taxes, because as

prices go up, theory says that the

quantities purchased should go down,

bringing tax revenues down with them.

In total, the general revenue funds of

the state have kept pace with inflation.

Salaries big part of state spending

What about the demands for state

expenditures? How have they responded

to inflation? About 35 per cent of

general revenue goes to operating state

government and about 60 per cent is

distributed in grants — primarily to

schools, other units of local

government, and public aid recipients. Of the

share that goes to running state government,

the largest portion, about 75 per

cent, goes to pay salaries and fringe

benefits. As salaries go, so go state expenditures.

Historically, salaries, salary increases

and cost of living adjustments have been

handled by the executive within the

Department of Personnel. A pay plan

has been worked out and money

included in each department's annual

appropriation bill. Legislative action has

been limited to approving the total

money for the department. In fiscal

1973, the cost of living increase granted

was 3.7 per cent. In fiscal 1974, the

legislature for the first time attempted

to legislate a pay increase for state

employees, responding to pressures

created when the new governor omitted

any pay increase in his proposed

budget. The General Assembly

proposed a 5 per cent increase but went

along with a counter proposal by the

governor which provided an increase of

$300 per year or 3.9 per cent, whichever

was greater, for each employee.

In fiscal 1975 the governor proposed

in his budget a similar sliding scale cost

of living increase which ranged from

$300 a year (approximately 7.5 per cent) for the lowest salaried employee

to $600 a year (approximately 2 percent) for the highest paid employee

with no increases given to those earning

more than $30,000 a year. For the

average employee the increase was 4.5

per cent. The legislature, however, passed

a bill requiring a $100 a month cost

of living increase for every employee.

The governor reduced the amount

$50, but the legislature overrode the

reduction and restored the increase to

the original $100 per month. To the

average state employee this represented

a cost of living increase of about 14 per cent.

Salaries keeping pace with inflation

Although there may be some lag, it

appears that state employee salaries a

keeping pace with inflation. The late

pay raise may be attributed, at least

part, to the increasing power al

militancy of public employee unions. I

those unions continue to grow and

collective bargaining becomes a reality,

upward pressure on salaries can be

expected to increase. Continued inflation

will be reflected more quickly in salary

adjustments. Lags will be shorter.

The other 60 per cent of the general

revenue budget is distributed in grants

with the largest sums going to schools

and public aid recipients. Prior to

legislative action in late 1974, public aid

recipients had not received a cost of living

adjustment in several years and had

to absorb all of the recent steep price

increases. (However, in switching to a flat

grant system in late 1973, the Department

ment of Public Aid said that the average

public aid grant increased 9 per cent.

For fiscal 1975, the legislature mandated

a 10 per cent cost of living

crease in public aid grants. The governor

reduced the increase to 5 per cent,

but again was overridden by the

legislature. This pattern can be expected

to be repeated. Public aid grants will

most likely lag behind any inflation

creating no pressure on the state. The

current situation is somewhat different

because inflation is combined with

recession. The squeeze on public

dollars is intensified by the recession

which has reduced revenues and swollen

public aid rolls. It is the swollen public

aid rolls and not the inflation causing

the problem.

It is difficult to determine

precisely what is happening in school

finances as a result of inflation. Costs

are going up, particularly for fuel

transportation. There is a limit on

|

68/Illinois Issues/March 1975

Governments must meet rising costs of goods and services. Sales and income tax revenues keep pace, but motor fuel and property taxes lage Among local governments, schools are feeling the squeeze most strongly

revenue. Without tax rate increases, it is clear that property tax revenues cannot keep pace with inflation, particularly in the short run. Existing property is scheduled for revaluation only every four years. In periods of rapid inflation there is natural resistance to "catching up" all at once. There has been some growth in the overall state property tax base, but this seems merely to have kept pace with the increase in population and the expanded economy, leaving nothing to offset inflation. (It is difficult to be more precise as property tax statistics are at least two years old, and it was in the 1972-73 period that personal property was removed from the tax base.)

With the lid on at the local level, with commodity prices rising, and increasingly militant teacher organizations bargaining for higher pay and increased expenditures, the inflationary pressure on schools has been passed on to the state. In the past two years state grants to schools have increased more than 35 per cent, and the pressure on the state for more does not seem to be abating.

Counties and municipalities have not been particularly hurt by this inflation. The property tax is playing an increasingly smaller role in county and municipal finance, while the sales, income and utility taxes which are all responsive to inflation are becoming more important. In addition, during the past two years federal revenue sharing has pumped new additional dollars into local government.

Highway financing seriously affected

Highway financing is the one area that has been seriously affected by inflation. The index on highway bid prices in Illinois has risen faster than the consumer price index. All levels of government have been affected. But highwayrevenues are not keeping pace.

There are four major sources of highway funds in Illinois: federal aid, the gasoline tax, motor vehicle taxes, and the property tax. As already noted the property tax does not keep pace. Federal aid has fluctuated, but receipts to the state in 1973 and 1974 were below receipts in 1972 and not much higher than receipts in 1971. If present trends continue revenue from the gasoline tax in fiscal 1975 will be little more than that collected in fiscal 1972. The higher prices, rationing, and lower speed limits have all contributed to fewer gallons purchased and therefore lower tax receipts. In a period of double-digit innation in construction costs, gasoline tax revenues rose only 4.5 per cent in 1973, 1.3 per cent in 1974, and in the first few months of fiscal 1975 have fallen 3.7 per cent.

Motor vehicle license revenues have also fallen behind the inflation rate. Fiscal 1973 revenues were up 8.4 per cent, but fiscal 1974 revenues were up only 0.4 per cent, and fiscal 1975 revenues are expected to rise only 0.7 per cent.

Crisis in highway funding

Highway financing in Illinois is facing serious problems. Adding to the crisis at the state level is recent legislation which has diverted highway funds. In 1973 a new law took the first $14 of each vehicle registration fee collected from Chicago residents and earmarked it for the support of a regional mass transit system. In 1975 this will mean $18 million less for state highways.

In 1974, over the governor's veto, the legislature changed the formula for distribution of gasoline tax revenues — reducing the state's share by about $15 million in 1975 and increasing the share going to counties, municipalities and road districts by the same amount. This will alleviate to some extent the highway problems which local governments are facing, but at the same time will increase the state's problems.

In the last quarter of 1974 there was increasing pressure on the President and the federal government to "do something" about inflation. One of the responses of the President was to propose cuts in federal spending which, if carried out, will affect state finances considerably.

Many of the original proposals changed federal matching grant requirements or reduced the scope of federal participation in welfare and social service programs. For example, the federal government has raised the percentage of income a family must spend on food before becoming eligible for food stamps, tightened the definition of incapacity for parents of dependent children, reduced the federal share of aid to dependent children grants, and required co-insurance charges for medicare and medicaid programs.

If all the proposals are carried out. the impact on state finances could be considerable. In fiscal 1975 it could mean a reduction of $100 million in federal aid accompanied by an increase of $80 million in required state general revenue spending. In fiscal 1976 the figures could balloon to a $230 million cut in federal aid with required increases in state spending of $170 million or a net increased burden on the state of some $400 million.

Recession plus inflation: disaster

Inflation, particularly inflation that has been fueled in part by large increases in the price of petroleum products, does have great impact on highway finances at all levels of government. A secondary problem area is education where inflation-fueled demands have caused and will continue to cause budget strains at the state level.

The foregoing discussion has dealt mainly with the effects of the inflation that ran from early 1973 to mid 1974 when the economy began to turn down and inflation became coupled with recession. The effects of this combination could be disastrous for state and local finance. Expenditures pushed by increased commodity prices, higher wage demands, and heavier public aid case loads will continue to escalate as revenues begin to turn down, leaving a gap that will be difficult to bridge.

March 1975/Illinois Issues/69