|

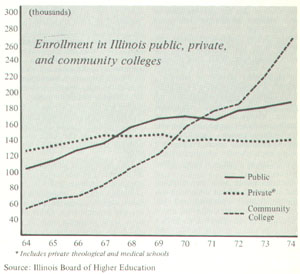

Fall |

Total |

Public |

Private* |

Community Colleges |

|

1965 |

313,324 |

114,594 |

134,782 |

63,948 |

|

1966 |

333,855 |

125,521 |

139,300 |

68,034 |

|

1967 |

363,061 |

137,561 |

142,254 |

83,246 |

|

1968 |

398,061 |

154,448 |

141,199 |

102,414 |

|

1969 |

431,980 |

167,653 |

141,482 |

121,845 |

|

1970 |

464,533 |

168,443 |

138,906 |

157,184 |

|

1971 |

482,413 |

167,076 |

139,478 |

175,859 |

|

1972 |

502,138 |

178,703 |

137,466 |

185,969 |

|

1973 |

542,764 |

180,876 |

136,936 |

224,952 |

|

1974 |

593,631 |

185,363 |

141,112 |

267,156 |

Enrollment figures are for students enrolls degree/credit courses.

* Includes private theological and medicals Source: Illinois Board of Higher Education

138/Illinois Issues/May 1975

An evaluation of Illinois public community colleges, their social and educational roles, and the growth and funding of a system whose enrollment now exceeds the public universities

advised to enroll in technical or vocational courses. In many cases this is the only option open to them if they cannot qualify for entry into college transfer programs. A majority of young high school graduates entering community colleges declare their intention to pursue studies qualifying them for transfer into senior institutions which grant advanced liberal arts or professional degrees. Only a small minority realize this goal.

What the community colleges do for many young students is to extend into higher education the lower school function of channeling students into occupational slots corresponding, in the majority of cases, to their economic and social class origins. This practice enables other colleges and universities in the state to maintain a selective function in preserving an intellectual and professional elite. The community colleges therefore do not truly represent an extension of educational opportunity but rather a more efficient way of screening out people from low income groups and perpetuating them in low paying and low status jobs.

These critics argue that the colleges shoul be concerned with the preservation of democratic ideals rather than concentrating so heavily upon job training. They contend that if we believe that public policy is or ought to be an exision of the popular will, then what better place can we find than the comnity colleges to develop leaders who provide political direction in interpreting the popular will and translating it into goals, policies and laws? What better institution could we find to educate the citizens who will determine policies administered by our future of state?

One top leader in the community college field believes the emphasis of the community colleges should be changed to serve as brokers in meeting all identified postsecondary educational needs through their own services or by referral to other appropriate institutions. Edmund J. Gleazer, Jr., president of the American Association of Junior and Community Colleges, is quoted in the November 25, 1974 issue of the Chronicle of Higher Education as saying that community colleges must have a new awareness of the educational market for developmental education, occupational education and other services. Gleazer does mention offering college-transfer courses as a function of the colleges, but he emphasizes career education and other community services for a clientele different from that of four-year colleges and universities. By implication the colleges are part of a specialized

hierarchy of higher educational institutions and not a competitive alternative to the existing system of elite schools that reinforce a process of selection which provides (or denies) credentials for entry into the managerial and professional classes.

It is popular at the moment for educators in universities, textbook publishers and other intellectual leaders to decry the loss of quality in U.S. higher education. In a recent issue of the journal Daedalus devoted to this subject. President Martin Meyerson of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia wrote that using colleges as "equalizing instruments" in society has produced a "leveling influence that has largely endangered quality."

May 1975/Illinois Issues/139

'Although Illinois' community colleges enroll more than half the students in public higher education in the state, they receive only 13% of the higher education budget. Similar slights are common across the country'

Equality, he goes on to say, "is a shibboleth in our country, and in questioning its universal applicability, one runs risks .... It seems clear that general equalization of budgets and salaries as well as admissions will lead to mediocrity."

Is it really so clear that equalizing budgets and salaries in higher education must lead to mediocrity? If so, then must the community colleges settle for second-class status from the viewpoint of quality? If the colleges attempt to be super-service stations for the community, providing a brokerage function for any and all kinds of services, there is a chance that the quality of services provided will suffer. And one may question whether tax-supported schools should train workers for local industry. Perhaps there are other forms of social organization that can provide some of these services in cheaper and more effective ways.

Proclaiming devotion to community service does not squarely meet the issues raised here. What kind of community services? It would be a challenging community service to provide a network of colleges offering a real alternative system of higher education to the poor, the black, ethnic minorities, women, displaced rural youth, the elderly, the handicapped and otherwise disadvantaged people ó many of whom may be difficult to teach. Perhaps our society needs liberally educated citizenparticipants as much as it needs skilled workers.

But this would be a very different kind of education from the service station for career coaching and job preparation. And it would require a reallocation of resources that could be a leveling influence, cutting heavily into the budgets of the more selective colleges and universities. This is an issue of great importance and one that merits full public discussion and debate.

Most of these colleges offer a variety of services to the public at the municipal or local district level. As they consolidate their enrollment gains and feel the political muscle that their combined size and budget allocations give them, the community colleges will be under pressure in coming years to define their social and political roles, and to defend their ever increasing demands upon the resources of the state. There is an unmistakable trend in Illinois and in the nation to shift an increasing proportion of the fiscal responsibility for these schools from the local district to the state.

Financing community colleges

And there are solid arguments for more state support. The writer of an article about Triton Community College at River Grove, Illinois, published in Time magazine December 3, 1973, observed that, "many legislators and establishment educators still treat Triton and its ilk like adolescent stepchildren. Although Illinois' community colleges enroll more than half the students in public higher education in the state, they receive only 13% of the higher education budget. Similar slights are common across the country. Yet for many students who aspire to being something between ditchdigger and nuclear physicist, the public community colleges are clearly filling an important void."

Like most states Illinois is assuming an increasing proportion of support for community colleges and will probably continue to do so. Competition for state funds makes college budgets a highly charged political issue. Other demands upon state resources such as welfare and public mass transportation are not likely to abate. The combined consequences of the present economic recession and the energy crisis will create demands for funds at both state and federal levels while the tax revenues will likely diminish if present predictions of employment levels are correct.

As the community college system grows, so will the influence of the . spokesmen who represent its interests in state politics. They will doubtless succeed in gaining a greater proportion of financing from state revenues, but transferring a major part of the cost of the colleges to the state merely shifts the financial problems without resolving them. The burden of taxation thus lifted from the backs of local property owners, must be shouldered by other taxpayersin the form of levies on income, luxury items, increased sales tax and so on. If this happened, the diffusion of tax sources would make it more difficult for taxpayers to combine in opposition to educational expenses since they are not so easily identified and organized as property owners are.

Schools, like other institutions, must reckon with the seemingly uncontrollable forces of inflation. Although the rate of enrollment increase has slowed, the community colleges are still growing at a much faster rate than the total population growth for Illinois higher education. The rate of community college enrollment is also expanding faster than the economic base for public education. As the competition for funds increases among educational institutions, the community colleges should have the political power to get a growing share of state resources. The social and political roles they play can exercise a powerful influence upon the whole of higher education in Illinois.

Control of community colleges

In three areas of college operation there will be a growing struggle for some measure of control over policy: (1) between the faculty and the administration of the college; (2) between the entire professional staff of the college including the administrators and the local political constituency; and (3) between the local governing boards and state agencies.

The struggle between administration and faculty will most likely focus upon conditions of employment ó salary, promotions, tenure, fringe benefits and upon the role of the faculty in governing the college. Many college faculties are embracing collective bargaining as an effective means of representing their professional interests Both the professional associations of teachers and the unions patterned upon

140/Illinois Issues/May 1975

industrial models are pursuing bargaining strategies. The Illinois Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO, the Illinois Education Association affiliated with the National Education Association, and the American Association of University Professors are all committed to collective bargaining as a way of protecting faculty interests and as a means of securing participation in policymaking.

The professional staff of the college will often be united in promoting the interests of the institution through bond referendums and in defending proposed tax increases in the face of growing opposition from community groups with different priorities in allocating public resources. For example, property owners, elderly citizens on fixed pensions and real estate interests have traditionally opposed large increases in property taxes. In the immediate future the community colleges will probably be forced into an aggressive political role in promoting their own interests. The struggle between local governing boards and the state regulatory planning and coordinating boards which implement legislative policy on higher education may be the primary arena of political contention in the near future. It seems clear that statewide planning for higher education is more efficient and less wasteful than the old pattern of individual schools vying for political and financial support. But it is not so clear that statewide master planning and control best serve the educational interests of the state and the educational needs at the community level. Many dimensions of our public life are involved in these questions about control of the community college ó the philosophical and theological realm of values, the basic economic structure of local society and broad questions of social policy. Most of these will be dealt with primarily through the political process. These will be some of the major issues in state politics during the coming decade.

More than a hundred years ago Lord Brougham said in a speech to the House Commons that education makes a people easy to lead but difficult to drive; easy to govern but impossible to enslave. If this is so, the politics of higher education in Illinois may have great portent for a constitutional republic preparing to celebrate the 200th anniversary of its founding. ź

Selected state reports

THE CRUCIAL CLASH between the individual's right to privacy and society's need to keep informational records has recently been the focal point for exhaustive study by a branch of the Illinois Department of Finance and two national information organizations. The resultant reports, one making legislative recommendations, the other offering administrative technical guidelines, are among the documents listed below in bibliographical form.

This annotated list has been compiled for readers of Illinois Issues by the staff of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois, Urbana.

State Documents

"Records, Privacy and the Law: A Need for Legislative Action," a paper jointly produced by National Association for State Information Systems (NASIS), the Government Management Information Sciences users group (G-MIS), and Project SAFE (The Secure Automated Facility Environment Project of the International Business Machines Corporation), [1974] 37pp.

"The Elements and Economics of Information Privacy and Security," a report of Project SAFE, [1974] 123pp. plus appendices."Recommended Security Practices:

Policies, Procedures, Guidelines, Responsibilities," [1974], a manual of Project SAFE. (Copies of these three reports are available from any district IBM office.)

These first two publications concern the conflict over the need of various parts of society to keep information and records and the individual's right to privacy. The first report traces the development of present law and proposes a model privacy law. The second is a study conducted in the Management Information Division of the Illinois Department of Finance. It is intended to acquaint departmental administrators with the issue of records and privacy and to provide guidelines for implementation of safeguards on records in their control. The third document is intended as a manual.

"Illinois Revenue Estimation: Fiscal 1974 Perspective and a Sales Tax Estimating Proposal," a report of the Illinois Office of the Comptroller (September 1974), 16pp. plus appendices.

Study No. 1 in the series Issues in Public Finance, this report develops an equation for more accurate prediction of Illinois sales tax yields.

"Patient Deaths at Elgin State Hospital," a Report to the General Assembly by the Illinois Legislative Investigating Commission (June 1974), 244pp.

A report into the deaths, under unusual circumstances, of several patients at a state facility for the mentally ill. Findings, conclusions, and recommendations of the commission are included.

"Report and Recommendations," of the Illinois Commission on the Status of Women to the Governor and the General Assembly (June 1974), 56pp. plus appendix.

A compendium of the reports of the commission's study committees on the inequities women face in such areas as education, pension rights, establishment of credit, and particularly employment.

"Today and Tomorrow in Illinois Adult Education," Final Report of the Task Force on Adult and Continuing Education, Illinois Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (February 1974), 48pp.

The 1970 Illinois Constitution mandates that adults as well as children be given free education through ihe secondary level. The task force was formed to study and report on current practices and to suggest legislation that would carry out the constitutional mandate.

Other Reports

Energy Conservation Policy Options for Illinois: Proceedings of the Second Annual Illinois Energy Conference, June 24-25, 1974, 222pp.

Available from Energy Resources Center, University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, Box 4348, 261 Roosevelt Road Bldg., Chicago, 111. 60680.

A collection of speeches and papers from sessions on (1) energy management in utilities; (2) energy conservation policy: and energy conservation in (3) the residential-commercial sector, (4) industry and agriculture, and (5) transportation.

"Rural Community and Regional Development: Perspectives and Prospects," a seminar series, spring 1973, conducted by the Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (June 1974), 108pp.

A collection of papers on the problems of rural areas and how these areas can be more fully utilized and the lives of their residents improved.

Items listed under State Documents have been received by the Documents Unit, Illinois State Library, Springfield, and are usually available from public libraries in the state through interlibrary loan. Requests for copies should be sent to the issuing agency.

State agencies are encouraged to send significant studies to the Institute of Government and Public Affairs for inclusion in the bibliography. Address items to the Institute, 1201 W. Nevada St., Urbana, Illinois.61801. ź

May 1975/lllinos Issues/141