FINAL ARTICLE IN A SERIES OF FOUR BY STEPHANIE COLE

A research associate at the Institute of Government and Public Affairs, University of Illinois, she is project director of the Illinois Home Rule Clearinghouse and Policy Analysis Project and editor of the Home Rule Newsletter published as part of the project.

Home rule in Illinois: No. 4. Local actions

The three previous articles in this series have described the innovative home rule provisions contained in Article VII, section 6, of the 1970 Illinois Constitution, the Illinois Supreme Court decisions affecting home rule, and the General Assembly actions. In this final article in the series, the implementation of home rule at the local level is considered

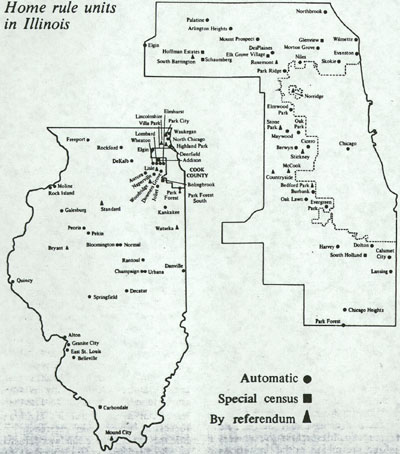

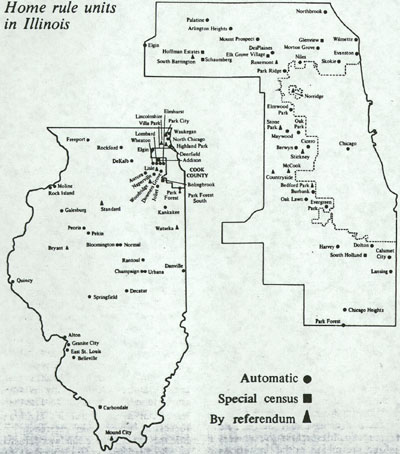

FROM THE EFFECTIVE date of the Illinois Constitution in July 1971 to the present, 18 Illinois municipalities under 25,000 population have voted by referendum to adopt home rule, and seven other municipalities have rejected this basic change in their governments. Why? And why was the home rule question defeated so overwhelmingly in the nine counties where the proposition has been on the ballot? How much of an impact has home rule had in the 87 Illinois local governments where it is in effect? To what extent has the functioning of local government been enhanced by the adoption of home rule? Although no final answers to these questions are possible yet, it does seem clear that home rule has permitted many local governments to handle—in their own way—a variety of local problems.

87 home rule units

Sixty-eight of Illinois' 86 home rule municipalities—cities, villages, and incorporated towns—acquired home rule status automatically because their populations exceeded 25,000. Cook County also acquired home rule status automatically because it had an elected chief executive officer. The 87 home rule units are shown on the next page.

Until a home rule unit enacts an ordinance which differs from a state law or which deals with a subject not covered in the statutes, it has the same relation to the state as a non-home rule unit. That is, state laws continue in force in home rule units until a home rule city or county takes an independent local action by its own ordinance. As expressed by Chicago attorneys Louis Ancel and Stewart Diamond:

"The majority of municipal attorneys believe that home rule municipalities retain the powers and are subject to the limitations of existing Illinois statutory law. To exercise its new powers a municipality must take some affirmative action. Thus, while a home rule municipality now, for the first time, may license general contractors, that power will only spring to life when a local ordinance so providing is passed. On the other hand, even if a home rule municipality took no new action, its licensing of restaurants, for example, would still be valid."

Discussing this point, the Local Government Committee of the Illinois Constitutional Convention stated in its report:

"Some may question why a local government should be forced to receive home-rule powers if they do not desire to do so. In response it should be noted that although all of the specified counties and municipalities will be empowered to undertake a wide range of activities under the ... section, no local government will be compelled to exercise these powers. The decision to act or not act will rest in every case with local officials, subject to the supervision of the citizenry at local elections."

Automatic by population

Most members of the Local Government Committee and other convention delegates felt that municipal home rule would be best suited to relatively large cities, villages, and incorporated towns. Consequently, in drafting the Constitution they included the proviso that municipalities under 25,000 may become home rule units only by voter approval in a referendum. To date there have been 18 successful and eight unsuccessful home rule referenda. In Stickney where home rule was defeated on the first try, voters approved the measure several years later. A home

August 1975/Illinois Issues/243

rule referendum may be initiated either by petition of the voters or by resolution of the governing board of the local government unit. Four of the 18 successful referenda were initiated by petition, but in all 18 cases, municipal officials, not the voters, first recognized the possibility for home rule for their communities.

Status gives power

In most of the 18 municipalities which voted to become home rule units there has been some special problem or set of problems which local officials felt could best be dealt with under home rule. In Stickney, for example, village officials wished to impose an admission tax on attendance at Hawthorne Race Course—a tax not permissible under state law for a non-home rule municipality. But after approving home rule status, Stickney was able to pass the tax, which is paid largely by non- residents. Similarly, one of Rosemont's major reasons for becoming a home rule unit was to enable it to impose a privilege tax on the use of the many local motel and hotel rooms. The village of Standard, the smallest (1970 population: 290) and one of the newest home rule municipalities, adopted home rule by the formidable margin of 96 to 4. The action was taken because the village wished to assume, by municipal ordinance, community development authority in order to apply for a grant under the federal Housing and Community Development Act of 1974.

|

Few generalizations can be drawn from the defeat of home rule in seven Illinois municipalities. Only one of these units—Arthur (straddling the line between Douglas and Moultrie counties)—is outside the Chicago metropolitan area. There were uniformly low turnout rates for these eight referenda (the measure was defeated twice in Long Grove), indicating a lack of public awareness and interest in home rule. Most of the successful referenda, however, were also characterized by low turnouts. Increased powers of taxation under home rule appear to have been the major issue in all the referenda. Perhaps the crucial variable is the extent to which local officials can convince voters that they do not intend to abuse this power. Officials in the nine municipalities where referenda were passed in April 1975 were careful to point out to voters that their present local taxation and debt levels were below the levels set by state law.

Counties need elected executive

In regard to county home rule, the "Con Con" Local Government Committee was mindful of the traditional weakness of Illinois county government. The resulting constitutional requirement provides that a county must have an elected chief executive officer in order to assume home rule powers. Cook County was the only county to have such an officer prior to the new Constitution, and thus was the only county qualified for automatic home rule status. The County Executive Act (Illinois Revised Statutes, 1973, chapter 34, section 701ff) provides the mechanism for electing this officer. The powers and duties listed in the act for county executive officers include the coordination and direction of all administrative and managerial functions of county government except those of other elected county officials; preparation of the annual county budget; and the appointment of members of various county commissions and boards, including boards of certain special districts.

Defeated in counties

To date, no county has elected to become a home rule unit, but nine have tried. In March 1972 the counties of DeKalb, DuPage, Fulton, Kane, Lake. Lee, Peoria, St. Clair. and Winnebago held referenda on the home rule-county executive question. In all nine counties the proposition was defeated by wide margins; the worst defeat was 9 to 1 in St. Clair County. A survey of knowledgeable observers of each county referendum was made by staff members at the Center for Governmental Studies, Northern Illinois University The following excerpts from the center's findings indicate some of the

|

244/Illinois Issues/August 1975

Home rule ordinances tend

to be tailored to the demands

of the local situation as

perceived by home rule officials

major reasons for the voters' rejection of home rule.

"STOP (Stop Taxing Our People) was actually a state-wide organization formed specifically to oppose adoption of county home rule. Headquartered in Chicago and directed by Richard Lockhart, an experienced state lobbyist, STOP coordinated state-wide efforts to defeat the proposal .... Lockhart stated that members of many professions, including physicians, dentists, engineers, and real estate brokers, felt that county home rule should be deferred until the state legislature passed House Bill 3636 to establish the state's exclusive right to license professions.* Lockhart also admitted providing background information to local opponents and speaking at meetings devoted to discussion of home rule.

"Lockhart's remarks are both consistent with and serve to reinforce our respondents' assessment of campaign activities. Members of professional occupations potentially subject to the licensing power granted home rule units were identified among the leading opponents of county home rule as individuals . . . and as members of organized groups .... Opponents were also perceived as more actively engaged in the distribution of campaign literature . . . the majority of which originated from local STOP committees.

" . . . . Visible opposition . . . was widespread among potentially influential individuals and organized groups. Opponents of county home rule communicated their arguments more effectively and in greater number than supporters. Supporters' arguments based on the need for professional administration, local control, and increased provision of needed services, were effectively countered by emotional warnings of new and increased taxes, licenses for professions and businesses, and excessive centralization of power in the county executive.

"It appears, as suggested by a respondent from Lee County, that 'the average citizen voted his fears of home rule' "—1972 County Home Rule Referenda, edited by David Beam, forthcoming 1975.

*Although House Bill 3636 (Public Act 77- 1818) was passed and signed into law, it was later declared unconstitutional for technical reasons unrelated to preemption by the Illinois Supreme Court (Fuehrmeyer v City of Chicago, 57 111. 2d 193 [1974}). A series of preemptive bills passed by the 78th General Assembly which are intended to correct these technical flaws was discussed in the third of this series of articles (July 1975, pp. 205- 207).

Local response to home rule

Four years have passed since the new Illinois Constitution went into effect on July 1, 1971. A variety of actions have been taken by home rule units since that time. Most of these actions could probably not have been taken under existing state statutes. A review of these actions shows that home rule officials have been able to respond to many different kinds of local conditions and needs, as anticipated by the Local Government Committee. A broad home rule grant "should stimulate initiative and vigor of local self-government to meet new and expanding responsibilities," according to the U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations analysis cited in the committee's report.

It should be noted that even when a number of home rule units pass similar ordinances dealing with a particular issue, the ordinances are not necessarily identical. They tend to be tailored to the demands of the local situation as perceived by home rule officials. Few "model" ordinances have been developed. The impetus for passing a particular kind of ordinance, however, often stems either from a favorable judicial ruling or from discussion at meetings of the Home Rule Attorneys Committee which is sponsored by the Illinois Municipal League.

Although there have been relatively few local home rule actions aimed at such pressing social problems as poverty and unemployment, some creative use has been made of new home rule powers. Stickney's racetrack admission tax and Rosemont's hotel-motel tax are two good examples. At least eight other home rule municipalities, including Chicago, have also imposed a hotel- motel tax. Chicago has been the first to institute several home rule taxes: a cigarette tax, an employers' expense tax ("head tax"), a parking tax, a transaction tax on real and personal property, and a wheel tax (also imposed by Cook County). All but the transaction tax have been upheld by the Supreme Court. This tax is now the subject of a suit filed recently in the Illinois Appellate Court, First District (Williams v. City of Chicago, Docket No. 61547).

Amusement taxes are in effect in Cicero and Villa Park; Oak Park has instituted a utility tax separate from the utility tax permitted municipalities under state law, and Evanston and Stone Park have imposed gasoline taxes. Although it may be argued that some of these measures are regressive and tend to fall upon those people least able to afford them, the taxes nevertheless have served to supplement static local budgets in a time of high inflation and increased demand for governmental services.

New ways to incur debt

Home rule units have also exercised great imagination in devising new ways to incur debt. The most widely used procedure is the issuance of general obligation bonds without prior approval by the local electorate. At least 16 home rule units have issued such bonds, and at least three other units have passed ordinances which authorize this procedure. (The significance of the

August 1975/Illinois Issues/245

Home rule is like sex—'when

it is good, it is very, very

good, and when it's bad, it's

still pretty good'

court case which upheld the right of home rule units to issue general obligation bonds without referendum approval was discussed in the second article in this series. May 1975, pp. 142- 144.) A number of home rule municipalities have used the Industrial Project Revenue Bond Act (Ill. Rev. Stat., 1973, ch. 24, sec. 11-74-Iff) in ways not conforming with state law. The intent of the act is to encourage industrial development by a liberal system of financing. Home rule municipalities have departed from the act by omitting the statutory seven per cent interest rate limit on bonds and by financing projects unauthorized under the state law.

Stretching the point?

There is some doubt whether the construction of pollution control facilities is permitted under the Revenue Bond Act, and at least eight home rule municipalities have enacted ordinances which specifically include such a facility as a permissible development. In addition, six of these municipalities (Addison, Alton, Danville, Decatur, Granite City, and Joliet) allow "any economic development project" which "will create or retain employment opportunities in [or near] the municipality." In Alton and Rockford, the procedures of the Revenue Bond Act have been adapted for hospital revenue bonds. Another widely used borrowing technique is the use of ordinary bank loans, not authorized by state statute, but often a convenient way to finance relatively small municipal expenditures. Such loans have been negotiated by at least seven home rule municipalities—Bloomington, Burbank, DeKalb, Highland Park, Mound City, Park Forest, and Stone Park.

Using their new powers, a number of home rule units have made changes in the structure of their governments. Cook County was sustained by the Illinois Supreme Court in its attempt to transfer the county clerk's function as ex officio comptroller to a newly created officer, a comptroller. Also upheld by the Supreme Court was the referendum procedure used by Arlington Heights to gain voter approval to appoint rather than elect municipal clerks and to increase the number of members of municipal governing bodies. State law contains no provisions for either measure. Bloomington, Normal, Park Forest, and Wilmette also now appoint their municipal clerks, while Highland Park has increased the size of its city council. A number of home rule municipalities have passed ordinances creating new boards, commissions, and departments.

Various changes in duties of local officers and employees have also been accomplished. These include increasing the power of city managers and redefining the personnel codes of firemen, policemen, and the duties of boards of fire and police commissioners. Other procedural changes have been instituted in the areas of assessment, budgeting, and the sale, purchase and leasing of municipal property.

Perhaps the greatest number of home rule ordinances have been enacted in the area of licensing and regulation. In June 1974 the General Assembly passed a number of preemptive bills, which took away the power of home rule units to license and regulate some 26 professions. Home rule units are free to continue to license and regulate in many other areas, however. For example, at least eight home rule municipalities have revised their review procedures regarding land use. Several environmental control ordinances have also been enacted; Cook County and Stone Park now license mobile homes and mobile home parks; and licenses for apartments, with the fee paid by the owner, are required by Arlington Heights and Oak Park.

Liquor, business regulations

Liquor control is another regulatory area in which a number of home rule municipalities have acted, especially in reaction to a state statute which allows 19 and 20-year olds to purchase and consume beer and wine. Seven home rule municipalities, all in the Chicago metropolitan area, have enacted ordinances which fix the drinking age at 21 for all alcoholic beverages, including beer and wine. These actions have been sustained at the appellate court level. In DeKalb, on the other hand, 19 and 20-year olds may consume all types of alcoholic beverages—a probable response to the large student population in the city. These different kinds of actions illustrate the ways in which home rule officials are able to take local conditions and preferences into account.

Home rule units have acted to regulate many kinds of businesses and commercial activities, although there is no clear statutory authorization for these kinds of regulations. These include collection of garbage, return of rent deposit, prevention of fraud, licensing and regulation of cats, inspection of automobiles, and bingo. Among the businesses and occupations regulated are massage parlors, motor vehicle towing services, private security guards, and installers of burglar alarm systems. At least nine municipalities have enacted comprehensive provisions which cover all businesses not specifically listed in other ordinances. Any of the 26 occupations covered by the recent series of state preemption statutes would, of course, be exempt from these ordinances, unless the state laws should be overturned in court.

Impact of home rule

As is evident from this discussion and from the previous articles in this series, home rule has brought about a fundamental change in Illinois government. No longer does the General Assembly exercise almost unlimited power over each and every aspect of local government. Through the constitutional provisions for preemption the legislature can, by positive action, take away many local powers and functions. The General Assembly has, however, acted with restraint. The courts, by their generally liberal series of decisions upholding local actions, have served to strengthen home rule.

Home rule has brought about a new, more open, relationship between state and local governments in Illinois. Whether this favorable climate for home rule will continue in the future remains to be seen. In the words of Local Government Committee member John Woods when he introduced home rule at "Con Con": "Home rule, many of you might know, is like sex—when it is good, it is very, very good, and when it's bad, it's still pretty good."

246/Illinois Issues/August 1975