By VITO C. BIANCO:

Associate superintendent of public instruction for Illinois, 1971-1975, he was responsible for that agency's collective bargaining policies as they pertained to school districts. He has negotiated collective bargaining contracts from both sides of the table and has served as a labor mediator for the past four years. Bianco is currently associate director of the Lilly-Northwestern Alternative Education Project at Northwestern University.

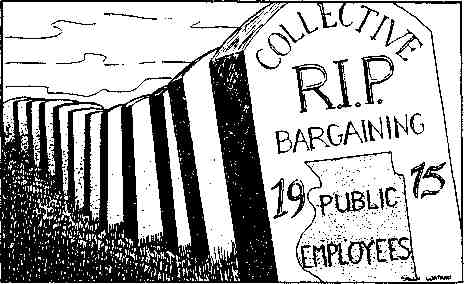

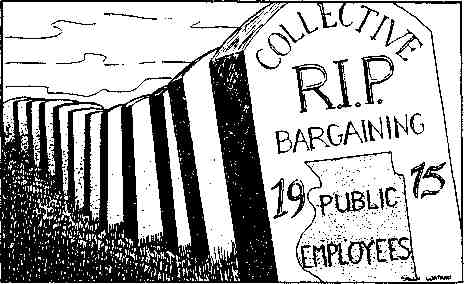

Again this year, the General Assembly did not pass a collective bargaining law for public employees. Establishing such a legal framework, the evidence suggests, might be in the best interests of state government

FOR MORE than 30 years, public employee unions and other organizations have sought the passage of legislation establishing a legal framework for the conduct of collective bargaining between public employers and their organized employees. This effort was again stalled by the Illinois Senate following its pattern.

When the General Assembly adjourned in June 1975, nine bills dealing with public sector collective bargaining were firmly sequestered in Senator Frank Savickas' (D., Chicago) Labor and Industry Committee most likely to be relegated to subcommittee status. Meanwhile, Illinois remains among the dwindling number of states—and the only large industrial state—which has not dealt with this question. At present, only 12 states have not enacted legislation dealing with this matter.

Past efforts

In 1945, the 64th General Assembly successfully passed a bill which would have given public employees the right to organize and bargain collectively, but the legislation was vetoed. It was sponsored by a Chicago Democrat, Sen. Roland Libonati, and had bipartisan support in both houses. The bill was assisted through the Illinois Senate by Richard J. Daley, then minority leader. Mayor Daley's connection with this effort is of some interest because during the spring session of the current General Assembly the so-called Daley Democrats in the Senate possessed enough votes to send any one of the nine bills to the governor, but did not choose to do so

The Senate Democrats from Chicago and a majority of Senate Republicans thought the issue needed further deliberation and that holding the bills in committee would be the best way to deal with the situation. Supporters felt that the time had come for the state to enact the legislation. Since 1945, when Gov. Dwight Green vetoed the public employee collective bargaining bill, legislation has been introduced in every session of the General Assembly. The legislation has generally been successful in the House of Representatives, but has always died in the Senate.

In 1967, the Governor's Advisory Commission on Labor-Management Policy for Public Employees unanimously concluded "that legislation defining State policy with regard to the rights and responsibilities of public employers and employees is imperative and in the public interest." In 1971, the Illinois Labor Laws Commission under the chairmanship of Sen. William Harris (R., Pontiac) recommended such a bill which was introduced but failed to pass. In 1973 and 1974, a like measure of the superintendent of public instruction for educational personnel was passed by the House and narrowly defeated in the Senate. Numerous proposals have been advanced on behalf of fire and police personnel which have met a similar fate.

Organizations such as the Council of State Governments, the Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, the National Governors Conference and the U.S. Department of Labor have all recommended that individual states develop legislative policies in this area.

While collective bargaining is a common occurrence in many Illinois school districts and in local and state government agencies, it is not as extensive as in states which have collective bargaining statues such as Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania. Sophisticated agreements and long standing bargaining arrangements exist in some areas of our state, but the aggregate level of activity in the bargaining arena lags behind those states with a statute. This is particularly true in the non-urban areas of Illinois where organizing may be more difficult and local public officials are not as likely to allow employee organizations to participate in determining wages, hours, and other conditions of employment. Therefore, employee unions have concentrated their efforts in the more populous areas where attitudes toward labor organizations are more favorable.

November 1975/Illinois Issues/335

Court decisions regarding collective bargaining for public employees lend some structure, but they leave large legal gaps

Collective bargaining agreements in Illinois contain provisions granting the majority organization exclusive bargaining rights, grievance procedures that end with binding arbitration, transfer policies, sick leave provisions, agency shop arrangements, and a host of other benefits found in the private sector. These agreements have been made in the absence of legislative authorization and are therefore continually under some legal question. In the absence of statute, the Illinois courts have been in a position to establish judicial guidelines under which (he collective bargaining process now functions. These court decisions lend some structure to the process, but they leave large legal gaps. A public employer or employee organization is therefore in a position of operating in a context where there is little in the way of ground rules. Consequently, confusion abounds and practical precedent rather than the rule of law often prevails.

Obviously the lack of a coherent policy often thwarts public employees from attaining benefits now enjoyed in the private sector. In some instances, local public bodies have refused to enter into contract negotiation, claiming the concept of sovereign authority while distrusting the political, economic, and social objectives of the labor organization. In other situations, the employer has entered into agreements that have eroded the authority of the public agency far beyond what may be considered prudent. With no legal framework under which to operate in Illinois, public employers and employee groups, within the confines of constitutional and case law (which must be interpreted anew over separate issues), are free to do as they please.

The courts have given some guidance in several areas. On the most thorny issue of public employee strikes, the Illinois Supreme Court held in Board of Education v. Redoing (32 Illinois 2nd 567 (1965]) that a strike by school custodians was illegal, stating "that a strike of municipal employees for any purpose is illegal." This language seems clear enough, but in a more recent decision in County of Peoria v. Benedict (47 Ill. 2nd 166 [1970]), and the case of Peters v. South Chicago Community Hospital (44 Ill. 2nd 22 [1969]), the court held that the state's Anti-Injunction Act was appropriate for all public employees except those employed by public schools. As a result of these decisions, the Illinois courts may not issue injunctions against strikes except when those strikes are by public school employees.

Public employers may enter into a collective bargaining agreement with a sole and exclusive agent. This was the ruling in the Chicago Division of the Illinois Education Association v. Board of Education (76 Ill. App. 2nd 456 [1966]).

As the legislature has failed to act, the judiciary of necessity has stepped into an area which is the proper province of the General Assembly. Moreover, judicial decisions generally apply to very specific situations and consequently each and every dispute that arises has the very real possibility of being litigated.

As the public employee unions continue to accelerate their efforts, the status of public sector labor relations becomes vastly more complex and increasingly more in need of the steadying influence that only a comprehensive law can provide.

At the present time, public sector labor unions are the fastest growing segment of organized labor. The American Federation of Stale, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) reports approximately 28,000 Illinois members. The Illinois Federation of Teachers has in excess of 40,000 members, including over 20,000 in the City of Chicago. The Illinois Education Association claims over 60,000 members—most of whom are in school districts outside of Chicago. The Illinois State Employees Association claims in excess of 15,000 members. There are also the police and fire organizations and a number of private sector unions such as the Teamsters, the Building Trades, and the Service Employees Union, which have markedly increased their public sector organizing efforts during the past few years. As the membership of these organizations grows, not only will public employees be able to exert more influence in the political arena, but they will also begin to have a much greater influence within the labor movement as a whole.

The most recent figures from the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1972) place the number of local governments in Illinois at 6,385. This includes counties, cities, townships, and school districts. These local governments employ approximately 350,000 workers; state government employs an additional 108,000. These figures show that the potential membership of the various organizations is great. The figures also convey the potential for confused collective bargaining activity.

336/Illinois issues/November 1975

The only statewide policy currently in effect is the executive order signed by Gov. Dan Walker on September 6, 1972. In that order, the governor granted the right to bargain to approximately 65,000 state employees under his immediate jurisdiction. The executive order established the Office of Collective Bargaining which in turn is responsible for establishing rules for the selection of an exclusive bargaining agent for the various categories of state employees. The executive order has had three noticeable effects. First, it has legitimized the process of collective bargaining for state employees. Second, the order has granted state employees those rights that other public employees may not have without action by the General Assembly. Currently, employees working for state agencies outside the governor's span of control do not enjoy the same rights as those covered by the executive order. Third, the public employee unions representing state workers under the executive order have been granted benefits that for years they have attempted to extract from the General Assembly. The Department of Personnel is now mandated to bargain collectively with a sole and exclusive agent. Union membership, while previously growing steadily, has been given an added boost by Executive Order No. 6, and this is by far the most significant effect of the governor's action (see March 1975, pp. 72-76 for further comment on Executive Order No. 6).

Current legislative proposals for public sector collective bargaining all possess provisions that deal with the several key or critical issues. These issues are:

(1) Coverage. The basic issues concerning coverage include whether a law should pertain to all public employees or exclude some workers because of the nature of their public employment. There are certain areas of public employment which may be more vital to the health or safety of the public than others; therefore, in some instances a comprehensive statute may treat certain workers with some variation.

(2) Unit determination. When bargaining takes place, it is important that the agent bargaining for employees represent a well defined organizational classification of employees. The question as to how appropriate classifications are to be arrived at may be left to the state agency administering the law, or may be subject to local determination.

(3) Supervisory employees. Determining who is a supervisor is much more complicated in the public sector especially in education where department chairmen and others have historically been in the bargaining unit. In nursing, the head nurse is in the same position. The problem of defining a supervisor is one of continual controversy since it can have a considerable effect on the membership of an employee organization.

(4) Scope. What is subject to negotiation? There are those who hold the position that any item of concern to either party is a proper subject for collective bargaining including such things as agencies' policy, budgets, transfers and layoffs. Of all the public employees, teachers generally view collective bargaining as a potential means of changing policy, and consequently, they have vigorously resisted attempts to limit the scope of bargaining. There are those on the management side of the table who would favor legislative directives eliminating certain "management rights" from consideration at the bargaining table in order to reduce the risk of a public employer negotiating away something that should have been retained.

(5) Union security. There are a variety of union security provisions that may be addressed, but the usual device in the public sector is the agency shop. The agency shop provision allows an exclusive bargaining agent (union) to collect a service fee for those who are in the bargaining unit but are not dues-paying members of the union. A law may be silent on this issue, prohibit such arrangements, mandate the agency shop, or cause it to be a topic subject to negotiation.

(6) Strikes. Public employees' right to strike is the most emotional issue of all. Even when this right is not questioned, the conditions under which it can be exercised have been debated furiously. At present only two states have, by statute, granted public employees the limited right to strike. Other states prohibit strikes by statute. Those states which permit strikes (Pennsylvania and Hawaii) do so only after the impasse provisions of the law are strictly adhered to. Even where strikes are prohibited and heavy fines are imposed on those who violate the law, strikes still occur. There are several ways in which legislation can deal with the strike issue. The General Assembly can (a) prohibit strikes and assess individual penalties; (b) prohibit with penalties on the striking organization; (c) prohibit with no penalty; (d) impose limited prohibition—making strikes legal only after impasse procedures are rigorously followed; (e) prohibit only for certain classes of employees such as police or fire workers; or (f) remain silent.

There have been several experiments with alternatives to the strike. The most common is the use of arbitration. This adjudicatory process involves a neutral

Bills on collective bargaining

|

Bill and sponsor |

Administrative agency |

Coverage |

Scope of negotiation |

Strikes |

Agency shop |

|

|

HB 1 |

Labor Relations Board |

All public employees |

Wages, hours, and other conditions of employment |

Permitted |

Permitted |

|

|

HB 489 |

None |

Educational employees |

Wages, hours, and other conditions of employment |

No provision |

No provision |

|

|

HB 1584 |

Law Enforcement Personnel |

Law enforcement officers |

Wages, hours, and other conditions of employment |

Prohibited |

Permits closed shop |

|

|

HB 2074 |

Employment Bd. Educational |

Educational employees |

Wages, hours, and other |

Permitted |

Permitted |

|

|

SB 730 |

Employment Bd. |

All public employees |

Excludes matters of inherent managerial policy |

Prohibited |

Maintenance of membership provision |

|

|

SB 752 |

Board of Arbitration |

Law enforcement officers |

Wages, hours, and other conditions of employment |

Prohibited |

No provision |

|

|

SB 817 |

Public Employment Board and Impasse Resolution Panel |

All public employees |

Wages, hours, and other conditions of employment |

No specific prohibition, but binding arbitration is mandatory |

Permitted |

|

|

SB 842 |

Public Employment Board |

All public employees |

Inherent management rights excluded |

Prohibited |

Maintenance of membership provided |

|

|

SB 1169 |

Public Employment Board |

All public employees |

Wages, hours, and other conditions of employment |

Permitted |

Permitted |

|

November 1975/Illinois Issues/337

At present, Senate Democrats from Cook County are not enthusiastic supporters of public employee collective bargaining legislation

third party who hears both sides of the controversy and makes a decision that may be binding on both parties.

The bills currently in the Senate Labor and Industry Committee all attempt to deal with the issues outlined above. For convenience, the bills are divided into three areas:

(1) Comprehensive, covering all public employees. H.B. 1 (Hanahan-D., McHenry). S.B. 730 (H. Mohr-R., Forest Park). S.B. 817 (Savickas), S.B. 842 (Glass-R., Northbrook), and S.B. 1169 (Bruce-D., Oiney).

(2) Public school employees, H.B. 2074 (Hill-D., Aurora) and H.B. 489 (Kelly-D., Hazel Crest, and Hanahan).

(3) Law enforcement personnel, H.B. 1584 (Telcser-R., Chicago) and S.B. 752 (Vadalabene-D., Edwardsville).

Bills in the first category covering all public employees deal with the major issues but treat them in vastly different ways. Each bill would create a state board (Stale Labor Relations Board in H-B. I and State Public Employment Relations Board in S.B. 730, 817, 842, and 1169). These boards would be vested with similar powers involving supervision and rulemaking authority over the conduct of elections to certify a sole and exclusive bargaining agent. The boards would also be responsible for determining the appropriate categories or units for collective bargaining purposes; providing mediation and/or fact-finding as well as determining unfair labor practices as defined in the bills, and would have broad supervisory powers, including subpoena, over public sector collective bargaining.

These bills all define unfair labor practices for employees as well as for employers. Under S.B. 730 and S.B. 842, strikes by public employees as well as picketing a public employer in a labor-management dispute are defined as unfair practices and would be prohibited. Both bills would empower the board to seek injunctive relief in strike situations and in other unfair labor practices. S.B. 1169 is silent on the issue of strikes, but does provide for binding arbitration when impasse results with units of police, fire fighters, prison guards, and security personnel. Binding arbitration would only be imposed after mediation, fact-finding, and advisory arbitrations have been unsuccessful in resolving the issue. Binding arbitration is provided in S.B. 817 after lengthy mediation and fact-finding. This bill is silent on the right to strike, but would empower a new Employee Relations Board to enforce the decisions of the arbitrator. H.B. I would permit a strike 30 days after mediation had been requested from a new State Labor Board by the public employees organization.

Limits on the areas subject to the negotiation process are contained in S.B. 730 and 842. In these bills, public employers would not be required to bargain over matters of "inherent managerial policy," which is defined as areas of discretion such as the functions and programs of the public employer, standards of services, its overall budget, the utilization of technology, the organizational structure, and the direction of personnel. H.B. 1, S.B. 1169, and S.B. 817 contain no limits on the scope of bargaining but instead would allow the negotiators the opportunity to determine what is negotiable.

The educational employee bills are interesting since they were introduced at the urging of the Illinois Federation of Teachers (H.B. 489) and the Illinois Education Association (H.B. 2074) to avoid the political problems of a comprehensive collective bargaining bill. Comprehensive bills have another problem because of the implications for the large number of county and municipal workers in Cook County and for their employers. Because of this, Senate Democrats, although traditional supporters of most labor legislation, have not been enthusiastic supporters of public employee collective bargaining legislation in the recent past. Teacher organizations (particularly the Illinois Education Association) felt that by introducing a specific educational employee bill, they would avoid any conflict with the public employers within Cook County and thereby draw the support of the Chicago Democratic senators. They even went so far as to exempt the City of Chicago from the provisions of H.B- 2074, but that effort failed in getting the bill out of committee.

H.B. 2074 covers educational employees and would create a separate State Educational Employment Board. This board would function in a manner similar to the boards previously mentioned in the comprehensive bills. Unfair labor practices are defined and strikes would be permitted after certain mediation procedures had been followed. As the bill is currently worded, ail school districts except Chicago would be subject to its provisions.

The most concise bill presented on the topic of public employee collective bargaining is H.B. 489 offered by Rep. Richard Kelly. This bill simply would grant teachers and other public educational employees the right to join unions for the purpose of bargaining collectively with their employers on salaries, other economic benefits, hours, working conditions and other mutually agreed upon items. It would also provide for binding arbitration of impasse should both parties agree, and specifically would include educational employees under the Anti-Injunction Act. The bill would not establish any new administrative agency nor provide for mediation or fact-finding.

The two bills dealing with law enforcement personnel are H.B. 1584 and S.B. 752. These bills are similar to the comprehensive public employee bills because they would establish administrative agencies to enforce their provisions. H.B. 1584 is very comprehensive since it would set up a Law Enforcement Personnel Employment Board which would supervise elections for the selection of a bargaining agent and would perform many of the functions outlined in the comprehensive bills. Both H.B. 1584 and S.B. 752 would prohibit strikes.

The major factor in the passage of any collective bargaining legislation will be the Chicago Democrats who hold enough votes to send a bill to the governor's desk. Before they will make that commitment they will have to be convinced that city and county governments will not have to give up certain powers they now enjoy. Perhaps the most accurate statement concerning the future public employee bargaining legislation is that it will become a reality when the mayor of Chicago decides its time has come.

The chart on page 337 summarizes the various provisions contained in the nine collective bargaining bills.ť

338/Illinois Issues/November 1975