By NORMAN WALZER and DAVID WARD

Walzer is associate professor of economics,

Western Illinois University, Macomb, and

Ward is a budget analyst with the state

Bureau of the Budget, Springfield. The

article is based partially on a study financed

by the Illinois Cities and Villages Municipal

Problems Commission and was prepared

while Ward was a research associate at W.I.U.

A big question looms for budget makers: Will Congress renew revenue sharing?

Launched in 1972, this new kind of federal aid

is due to expire this year. It provides a tenth

or more of local government funds in Illinois,

and over $100 million to the state. If it is cut off, some governments will feel the pinch

THIS IS the year of decision for General

Revenue Sharing (GRS). Begun in 1972,

this program will have provided $30.2

billion to state and local governments

when it expires December 31, 1976 —

unless Congress extends it. The revenue

sharing monies are allocated to state

and local governments to spend for

broad classes of general purposes in

contrast with the traditional practice of

grants-in-aid for particular programs.

But because of uncertainty as to what

Congress will do, no one can count on

this money in planning a budget after

1976. And if this relatively unfettered

form of federal aid is cut off, the fiscal

crisis facing many state and local

governments in the nation will be

significantly worsened. In the case of

Illinois, local budgets could lose 10 per

cent or more, and the state government

could lose $100 million. The loss of such

an amount today would wipe out the

general fund available balance in the

state treasury — this is a measure of

what GRS has come to mean in dollar

terms.

Because GRS represented a major

change in the method of allocating

federal funds to local governments, it

has attracted a substantial number of

critics. Some have favored more guidance from the federal government in the

use of these funds, while others favor

completely eliminating the program and

returning to the more traditional approach of providing grants-in-aid for

designated activities. In addition, there are those who question why we should

collect taxes and send the money to

Washington — and then turn around

and send it back to the states and local

units. Finally, with the White House

turning on the pressure for federal

budget cutting, some members of

Congress would like to respond by

axing the revenue sharing program.

How is this going to affect Illinois?

How have this state and its local units

shared in the distribution of the $30.2

billion appropriated for GRS over a

five-year period? What uses have they

made of the new money? What activities, by implication, will suffer or be discontinued if GRS is not renewed? And what are the prospects for Congress to

extend it or change it?

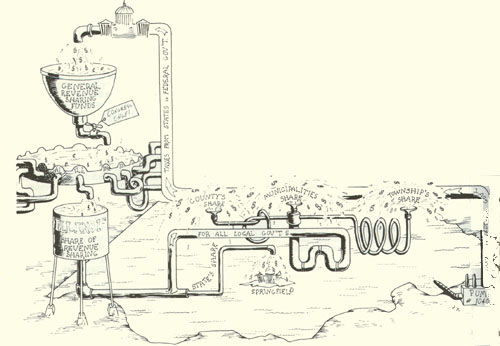

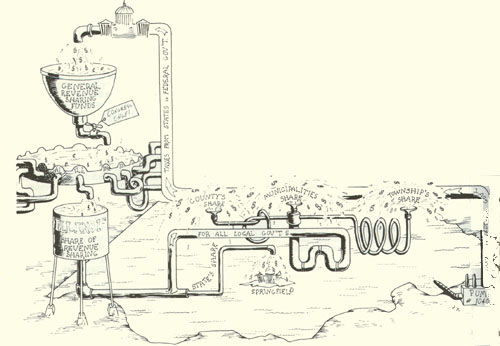

How GRS is distributed

Local Fiscal Assistance

Act of 1972 (Public Law 92-512), which

established GRS, was the product of

many compromises in Congress. One of

the most important compromises concerned the formula for distribution of

the money ($5.3 billion for the first year)

among state areas. The U.S. House of

Representatives formula favored the

highly populated and industrialized

states, such as Illinois. The Senate

formula favored low-income states with

heavily rural populations. The final

compromise retains both formulas (see

sidebar), and the Illinois share is based

on the House formula because it favors

Illinois more than the Senate formula.

Through June 30, 1975, as shown in table 1, the formula has entitled this

state and its counties, townships, and

municipalities to more than a billion dollars.

One-third of the amount allocated to

Illinois must go to the state government.

The remaining two-thirds goes to local

governments within the state — counties, townships and municipalities (cities

and villages). This two-thirds is allocated into shares for each of Illinois' 102

counties, using population, relative

income, and tax effort (see sidebar). The

allocation for each county is then

distributed among the county, township

and municipal governments in the

county. The county government's portion is based on its share of tax collections within that county, and so is the

share that goes to townships. (In the 17

counties that do not have townships, no

allocation is made to townships, of

course, so the GRS funds for these

counties are shared only by the county

and municipal governments.) After

removing the share for the county and

townships, the remainder is allocated

among municipalities, using the factors

of population, relative income, and tax

effort. Municipalities, as shown in table

1, receive the largest portion of the

revenue sharing monies going to Illinois

local governments.

School districts and other special

district governments (sanitary districts,

fire protection districts, etc.) are not

included in the federal law's definition

of local governments for GRS and do

not share in the distribution, nor are their tax collections counted in the tax effort formulas.

March 1976 / Illinois Issues / 3

'Many bills have been introduced in Congress containing some rather drastic changes in the revenue sharing program'

The allocation formulas are complex, but the federal Office of Revenue Sharing, a part of the Treasury Department, publishes the amount to which each governmental unit is entitled as well as the factors on which the amount is based. A recipient government can challenge the accuracy of the figures if it wishes.

The minimum payment which can be made to a governmental unit is $200; a unit whose entitlement is less than this amount receives nothing. No unit of government can receive more than 50 per cent of the sum of (1) its adjusted local taxes and (2) intergovernment revenue. The payment to a local government is also affected by a per capita test which limits the range of payments by eliminating the extremes. The standard here is the statewide average per capita of total payments to all local governmental units. A local unit is guaranteed a payment which, when computed on a per capita basis (payment divided by population) equals at least 20 per cent of the statewide average per capita but does not exceed 145 per cent of the statewide average.

How significant in Illinois?

GRS payments represent a substantial proportion of the income of local governments, as shown in table 2. For townships as a class, this source on the average accounted for almost 23 per cent of their income during the period July 1, 1973, through June 30, 1974; for the smaller cities (below 5,000 population) it represented 12 per cent on the average. Other classes of local governments fell between these extremes.

The table also shows average per capita amount of GRS by class of government. The largest average per capita amount, $9.32, went to municipalities of 5,000 and above. Municipalities under 5,000 were allocated the smallest average per capita amount, $6.59.

The table shows how the 145 per cent and 20 per cent limitations mentioned above affect these governments. Of 2,808 units of government in Illinois receiving GRS, approximately 680 were affected by one of the limits. A Ford administration proposal for renewing GRS, introduced early last year, would increase the upper limit of 145 per cent to 175 per cent. Table 2 indicates this would affect 42 Illinois units — that is, they would receive more. But note that no municipality of 5,000 or above would be affected by raising the 145 per cent limit. However, the bottom limit of 20 per cent did benefit 21 of the larger cities. Although much of the pressure nationally to increase the upper limit has come from large urban areas, Chicago was not constrained by the 145 per cent ceiling according to this data. A much more substantial impact would occur in Illinois if the floor of 20 per cent were altered.

But a problem for Chicago has been with the federal nondiscrimination provision which has been the basis for federal court action withholding GRS funds from the city. Alleged discriminatory hiring and promotion practices in the Chicago police department are involved. The amount withheld from Chicago is included in table 1, however.

How the money is used

Units of local government are permitted to spend revenue sharing funds according to "priority expenditures" as set forth in the federal act and in accord with state laws and regulations governing the use of state funds; a major exclusion from permitted spending is education.

To determine that funds are being used lawfully, recipient governments are required to file "Actual Use Reports" at the end of each payment period. For all intents and purposes these reports are the most comprehensive data available on the use of GRS funds. But Actual Use Reports have been criticized because they are ambiguous. The categories listed are broad, and local officials in two

4 / March 1976 / Illinois Issues

|

Table 1. Revenue sharing allocations to Illinois

governments, January 1, 1972-June 30, 1975

|

|

| |

Level of govt. Dollar amount Per cent |

|

State $347,441,827 33.3 |

|

Local governments

694,983,589

66.7 |

|

counties

(155,568,698) (14.9) |

|

municipalities¹

(448,312,636) (43.0) |

|

townships ( 91,102,255) ( 8.7) |

|

Total state & local $1,042,425,416 100.0 |

¹Includes payment (approximately $57 million) withheld from Chicago

because of the discrimination claim described in the text.

Source: Illinois Commission on Intergovernmental Cooperation |

|

different units of

government can report the same type of

project under different categories.

Second, there is a possible "displacement effect" because GRS funds can be

used for a particular purpose and

thereby free up locally raised funds for

other projects.

The inability to trace the use of funds

has been especially criticized by the

federal General Accounting Office, but

the problem is not unique to revenue

sharing. It exists, at least theoretically,

in virtually all intergovernmental fund

transfers (that is, grants-in-aid or shared

revenues).

The information reported by Illinois

governments during the period July I,

1973, through June 30,1974, is shown in

table 3. The use of per capita (per

resident) figures in the table permits

comparisons among governments of

different populations.

|

Because of the differing functions and

services provided by local governments,

one can reasonably expect there would

be substantial differences among the

uses reported. At each level of government, a larger number of governmental

units reported GRS spending for capital

projects than for operating and maintenance activities. This was probably to

be expected since capital expenditures

include buildings, equipment purchases

and other nonrecurring items. Because

of the temporary nature of revenue

sharing, local officials were advised

against initiating programs which could

not be maintained without a tax increase. Given a choice between a capital

project and a possible increase in

personnel, officials were advised to

choose the "one time" projects.

The amounts spent for capital projects also exceeded those for operating

and maintenance, except in the case of

counties. Although more counties (87) reported spending on capital rather than

on operating and maintenance purposes, the per capita amount spent on

the latter was $6.02, which exceeded the

$3.37 spent on capital projects.

The revenue sharing program has

been sharply criticized because it did not

stimulate more "people-oriented" programs. This criticism should be considered in the light of recent economic

trends. There is considerable evidence to

suggest that, at least in the case of

municipalities, the GRS payments

received by local units were not sufficient to offset the impact of inflation.

In this type of economic climate, one is

unlikely to find new and innovative

programs being developed since, in

many cases, it was a struggle to maintain

existing programs.

What will Congress do?

With budget preparations already

begun for the next fiscal year, local

officials are understandably concerned

about the future of GRS. Many bills

have been introduced in Congress

containing some rather drastic changes

in the program. Because the program

was not re-enacted last year, the proposals will probably become entangled

in the new Congressional budget reform

proceedings (see "Can Congress make

fiscal policy? New budget system on trial

this year," Jan. 1976, p. 31). This could

delay re-enactment until after mid-May

of this year.

At the close of 1975, more than 20

bills were pending before the House

Government Operations Subcommittee

on Intergovernmental Relations chaired

by Rep. L. H. Fountain (D., N.C.).

These included the administration

proposals (S. 1625 and H.R. 6558)

which would distribute $39.85 million

from 1977 through September 1982,

representing an annual increase of 2.5

per cent above the current funding level.

Other key factors of the administration

proposals involve: increasing the 145

per cent limit on payments (see above)

to 175 per cent over the renewal period

(six percentage points each year); requiring recipients to give notice to

citizens of intended uses of the funds

and the opportunity to participate in the

decision making; allowing the secretary

of the treasury to waive the publication

requirement for use reports and make

reporting requirements more flexible; and making GRS immune to the Congressional Budget Act's annual appropriation process.

The language of revenue sharing

HERE, excerpted from the federal act,

is the Senate's three factor formula for

determining the amount allocable to a state

area: "the amount which bears the same

ratio to $5,300,000,000 as —

(A) the population of the State, multiplied

by the general tax effort factor of the

State, multiplied by the relative income

factor of that State, bears to

(B) the sum of the products determined

under subparagraph (A) for all States."

The House's factor formula is even

more complex: "the amount to which

that State would be entitled if —

(A) 1/3 of $3,500,000,000 were allocated

among the States on the basis of population.

(B) 1/3 of $3,500,000,000 were allocated

among the States on the basis of urbanized

population.

(C) 1/3 of $3,500,000,000 were allocated

among the States on the basis of population

inversely weighted for per capita income.

(D) 1/2 of $1,800,000,000 were allocated

among the States on the basis of income

tax collections, and

(E) 1/2 of $1,800,000,000 were allocated

among the States on the basis of general

tax effort."

Every state's allocation must be figured

both ways and its allocation is based on the

higher amount. But because this approach

allocates more than the total available —

$5.3 billion in the initial period of GRS —

final allocations to each state are

proportionately reduced.

"General tax effort" is the net amount

of tax collections (State and local, or local,

as the case may be) divided by aggregate

personal income of the state or locality.

"Adjusted taxes" are taxes collected

for general purposes excluding amounts

allocable to expenses for education, special

assessments, and the like.

"Intergovernmental transfers" are

amounts of revenue received by a

government from other governments as

a share in financing the performance of

governmental functions — for example,

grants-in-aid.

"Relative income" is a fraction. In

the case of a state, the numerator of the

fraction is the per capita income of the

United States and the denominator is the

per capita income of the state. In the case

of a county area, the numerator is the per

capita income of the state, and the

denominator is the per capita income

of the county area. In the case of a unit

of local government, the numerator is the

per capita income of the county area,

and the denominator is the per capita

income of that unit.

Had enough?

March 1976

/ Illinois Issues / 5

Table 2. Revenue sharing allocations to Illinois local governments, July 1, 1973-June 30. 1974

|

|

|

|

No. of governmental units |

|

|

Per |

Per cent |

Total |

Affected by limits |

|

|

capita |

of local |

no. |

20% |

145% |

|

Level of gov't. |

receipts |

income¹ |

|

|

|

|

Counties |

$ 7.34 |

16.4 |

102 |

0 |

5 |

|

Townships |

8.74 |

22.7 |

1,436 |

391 |

24 |

|

Municipalities: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below 5,000 pop. |

6.59 |

14.5 |

1,018 |

233 |

13 |

|

5,000 and above 3 |

10.01 |

12.0 |

252 |

20 |

0 |

¹Approximated by the sum of intergovernmental transfers andadjusted taxes. Since this understates total revenue, the percentage is slightly overstated.

²See text for explanation of these limits.

³Includes Chicago.

Source: Office of Revenue Sharing and Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations

Other bills receiving consideration

during the subcommittee hearings

included H.R. 8329, introduced by Rep.

Robert F. Drinan (D., Mass.), which

would extend GRS but require annual

appropriations and make rather sweeping changes. His bill would require

states and local units receiving at least

$500,000 to spend 10 per cent of their

allocations in each of the following

priority areas: public safety, environmental and consumer protection, public

transportation, health and recreation,

and social services and housing for the

poor and aged. States would have an additional priority area, education. The

bill would give each state government

the option of dividing its total GRS

money among the state and local

governments according to comparative

tax efforts rather than the present

division of one-third to the state, two-thirds to local units. The 20 per cent

minimum would be eliminated, and the

145 per cent ceiling would be raised to a

whopping 300 per cent. These changes

would affect many Illinois governments

as indicated in table 2.

Table 3. Actual use of revenue sharing by Illinois local governments, July 1, 1973-June 30, 1974

Numbers in parenthesis show number of units reporting an expenditure in category

|

…Municipalities…

|

|

Categories |

Counties .... Townships …. |

Below 5,000 |

5,000 and more |

|

|

(100) |

|

(1217) |

|

(819) |

|

(186) |

|

|

Operating and maintenance |

$6.02 |

(76) |

$5.02 |

(638) |

$4.63 |

(375) |

$2.89 |

(105) |

|

Public safety |

3.22 |

(65) |

2.40 |

(51) |

3.89 |

(165) |

2.08 |

(62) |

|

Environmental Protection |

.53 |

(13) |

.87 |

(30) |

3.62 |

(72) |

1.33 |

(28) |

|

Public transportation |

4.02 |

(25) |

7.13 |

(391) |

4.72 |

(94) |

1.48 |

(29) |

|

Health |

.61 |

(22) |

.80 |

(64) |

3.25 |

(54) |

1.21 |

(22) |

|

Recreation |

.19 |

(5) |

.50 |

(37) |

1.17 |

(61) |

.69 |

(25) |

|

Libraries |

.43 |

(3) |

.51 |

(31) |

.75 |

(28) |

.45 |

(12) |

|

Social services |

.33 |

(18) |

.58 |

(66) |

.64 |

(19) |

.48 |

(18) |

|

Financial administration |

2.11 |

(53) |

.40 |

(319) |

.91 |

(121) |

.57 |

(37) |

|

Capital |

$3.37 |

(87) |

$8.52 |

(979) |

$8.01 |

(672) |

$8.07 |

(170) |

|

Public safety |

1.93 |

(52) |

3.97 |

(112) |

4.85 |

(271) |

3.28 |

(108) |

|

Environmental protection |

.29 |

(6) |

1.26 |

(25) |

5.02 |

(104) |

4.04 |

(50) |

|

Public transportation |

1.78 |

(28) |

8.99 |

(689) |

5.31 |

(135) |

3.28 |

(42) |

|

Health |

.95 |

(9) |

1.71 |

(45) |

6.33 |

(124) |

3.19 |

(17) |

|

Recreation |

.10 |

(2) |

2.47 |

(56) |

3.44 |

(138) |

2.08 |

(42) |

|

Libraries |

— |

— |

1.27 |

(62) |

2.38 |

(30) |

1.17 |

(20) |

|

Social services — aged |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and poor |

1.83 |

(8) |

.70 |

(39) |

1.22 |

(9) |

.82 |

(5) |

|

Financial administration |

1.85 |

(17) |

.30 |

(106) |

.83 |

(43) |

.18 |

(13) |

|

Multipurpose and general |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

government |

1.55 |

(49) |

4.02 |

(278) |

4.74 |

(191) |

3.06 |

(49) |

|

Education |

— |

— |

1.07 |

(10) |

1.23 |

(6) |

.11 |

(2) |

|

Social development |

.76 |

(4) |

.44 |

(7) |

2.57 |

(6) |

.41 |

(4) |

|

Housing and community dev. — — |

2.82 |

(34) |

5.46 |

(52) |

3.45 |

(6) |

|

Economic development |

.76 |

(2) |

1.87 |

(2) |

5.27 |

(32) |

.43 |

(7) |

|

Other |

.95 |

(4) |

3.42 |

(24) |

4.64 |

(15) |

4.73 |

(56) |

|

Source: Office of Revenue Sharing

|

Four bills would eliminate state

governments from receiving GRS: H.R.

8170 and H.R. 9245 by Rep. Robert H.

Mollohan (D., W. Va.), H.R. 9629 by

Rep. Jerry Litton (D., Mo.), and H.R.

10221 by Rep. Wilbur D. Mills (D.,

Ark.). Other bills would double the

allocation of funds (H.R. 4305); prohibit the distribution of funds except

when the federal budget is balanced

(H.R. 1318); require compliance with

the Fair Labor Standards Act (H.R.

9137); provide automatic cost-of-living

adjustments (H.R. 5687); and include

services provided by special districts in

the tax effort computation (H.R. 4607

and H.R. 5454).

Support for re-enactment is reported

to be fairly strong with particular

support from Sen. Edmund S. Muskie

(D., Me.), a long time advocate of the

revenue sharing concept who is now

chairman of the Senate Budget Committee. The administration proposal

attracted 35 senators and 51 representatives as cosponsors.

But opposition is strong, and Chairman Fountain of the House Intergovernmental Operations Subcommittee accurately predicted last year that reenactment would not occur in 1975. He

is said to be determined that his subcommittee will exhaustively examine the

current program before any legislation

is reported to the House floor. Both

Rep. Jack Brooks (D., Texas), chairman of the Government Operations

Committee, and Rep. Brock Adams

(D., Wash.), chairman of the House

Budget Committee, have come out

against continuation of GRS.

The Presidents proposed budget cuts

may also jeopardize re-enactment of

revenue sharing. Rep. Al Ullman (D.,

Ore.), chairman of the powerful House

Ways and Means Committee, is reported to have said, "It is the mood of

Congress to eliminate federal revenue

sharing — probably all of it — if that

body is called on to make severe budget

cuts." Finally, a perceived lack of active

campaigning on behalf of GRS by the

states and local governments is reported

to have had a negative impact on efforts

for re-enactment.

The prospects are for a spirited and

tough struggle over the continuation of

GRS. State and local governments

stand to lose a sizable amount of

revenue if the program is not re-enacted,

and the loss would come during a period

of unprecedented inflation. There is

little question that local taxes will be

increased in many areas if a revenue

sharing program of some kind is not

continued. Since property taxes and

sales taxes (the major sources of funding

for local units) are thought to be more

regressive than the federal income tax

(source of GRS funding), the prospect

of local tax increases is likely. Reverting

to a complex system of federal grants

rigidly earmarked for particular programs would have the effect of transferring local decisionmaking power to

Washington. Whatever the outcome, it

appears likely that local officials will

have to begin budget preparations for

the next fiscal year with considerable

uncertainty as to what they can expect

from federal revenue sharing.

6 / March 1976 / Illinois Issues