By JOHN REHFUSS and DAVID TOBIAS is a professor and David Tobias a graduate student of political science at Northern Illinois University, DeKalb. Both are associated with the Center for Governmental Studies.

Special districts: The little governments providing specialized services

SPECIAL districts mirror very closely the essential character of the American people. They have most of our strengths and weaknesses and represent most of our values, both good and bad. Our national lack of long-range planning and our preference for "ad hoc" arrangements are dramatically illustrated in Illinois by a look at special districts that exist outside the more general governments of municipalities, counties and townships.

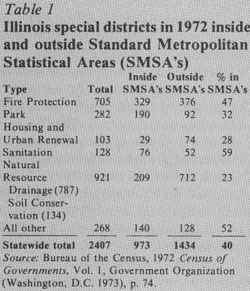

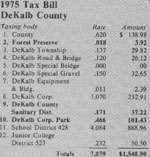

Special districts are created to provide specialized services at the grass roots level and, with the exception of some "giants" such as the Chicago Metropolitan Sanitary District, are usually very small and limited in size and scope of their operations. They differ in methods of obtaining revenue, how their governing board members are selected and to which state entity a petition would be filed to form a district. Table 1 shows the number and distribution of the six major types of special districts in Illinois, and table 2 shows their basic characteristics.

| Districts are considered "municipal corporations." They can sue and be sued; enter into binding agreements; have their own seal; have perpetual succession; buy, rent or lease land or equipment; hire employees; and usually condemn land for legitimate district purposes. They are, in every respect, little governments. Districts also have limits on their tax rates; these generally can be raised by public referendum (with the exception of conservation districts, which cannot make binding levies or assessments). In most cases, bonded indebtedness can be incurred by referendums, with a maximum set by law. |  |

In very general terms, most Illinois special districts have basic similarities. First, residents who do not wish to be included in a proposed district usually are able to challenge their inclusion either through litigation or petitions to disconnect. This right is usually based on an alleged failure of the district to prove that services are benefiting a resident who usually must prove he is a property taxpayer or is somehow charged for services. Sometimes these challenges prevent the formation of a district. Complaints about inclusion, of course, are strongly related to the amount of taxes levied upon district residents.

Members of district governing bodies rarely receive much remuneration for their services and usually serve for the reward of believing they have made a contribution to a valued end. They are either unpaid or receive a small stipend, with reimbursement for district business expenses.

The relationship between benefits and costs varies greatly. At one extreme, fire protection services are a "pure public good," available to everyone at a uniform levy. At the other extreme, drainage and conservation districts levy charges or benefit assessments directly calculated on the expected benefits. In the case of drainage districts, these benefit assessments are very similar to property taxes and constitute a lien on property in the event of nonpayment.

Most districts represent specialized interests. They have responsibility for a specific function and carry it out with intense dedication. They make good "watchdogs" over general purpose units when their own function is at stake and can be trusted to make a loud public outcry when there is a conflict. Public conflict is infrequent, however, for districts are relatively shielded from public view. Only park districts and drainage districts have elected commissioners — the rest are appointed, usually by county boards, who often follow the advice of existing district board members or reappoint the incumbent. District elections tend to receive little attention, particularly for drainage districts when only benefited property owners vote and often five votes or less settle an election. Districts prefer anonymity because it gives them more flexibility to operate outside the scrutiny that municipalities undergo, and it preserves their preferred financial position.

The DeKalb example

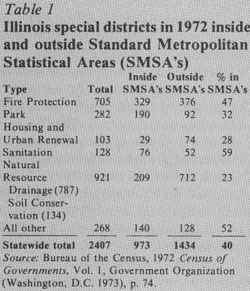

To understand the special districts individually, the DeKalb County example is one place to begin. A typical tax bill received in DeKalb County is shown below. The taxing bodies on the bill include (1) the county, (3-7) the township, (8) the city, (11) the school district, (12) the junior college district,

22 / September 1977 / Illinois Issues

The DeKalb forest preserve is one of nine in the state (in 1973); all but two (Piatt and DeKalb) of Illinois' forest preserve districts are in metropolitan areas. They are governed by the county board members and usually are coterminous with county boundaries, although they can be smaller. They serve primarily to preserve open space and provide recreational space.

Park and sanitary districts are much more common and more important than other special districts in Illinois. There are about 150 or more sanitary districts in the state, and they have an extraordinary impact on their communities because of the way that they affect land development. Several districts have, over various periods of time, declared moratoriums on sewer connections, which has frustrated the plans of municipalities and/or counties.

The DeKalb Sanitary District has a tax rate (.171) lower than most districts in the state, which ranged from no levy up to .960 in 1973. The low rate is helped by having day-to-day operations financed through a charge included on the city water bill, then remitted to the district for a small handling charge. This revenue permits the use of property tax revenues to retire bonds, with the balance of operating revenues coming from an acreage charge for annexations as well as miscellaneous revenues including charges for using or connecting to sewers.

DeKalb is a medium sized sanitary district, originally larger than the city, but now roughly coterminous. About half its sewer mileage is owned and maintained by the City of DeKalb, which will presumably turn it over when it is upgraded with community development funds. Complex cooperative arrangements like these are relatively common between sanitary districts and municipalities.

Land development is a constant factor in the calculations and activities of the district. One large shopping center north of DeKalb built its own treatment plant instead of hooking onto the district and created a situation which has been controversial ever since. Another dispute was with Northern

Illinois University in 1965, when university growth led the district to declare a moratorium on sewer connections. The stalemate was resolved only when the university agreed to help cover the costs of new facilities. Most disputes have been with developers rather than with other government bodies.

| District board members were selected by the circuit court judge until 1973, when legislation implementing the new Constitution gave appointive power to the county board of supervisors. Generally, very influential members of the community have been selected as sanitary district board members. In DeKalb, members include the president of one of the major banks in the city (who has been on the board for 15 years), a downtown merchant and a welding contractor. |  |

Virtually coterminous with the city, DeKalb Park District is by far the largest of the six park districts in the county, although it is not large in comparison to districts across the state, particularly in the Chicago area. It enjoys an excellent relationship with the school district. As is common, school

facilities are used for park district activities in both winter and summer. The district has paid for installation of lights on school tennis courts and built a $100,000 heating plant for one gym where joint programs are carried on. The major park district programs, including swimming, are conducted in the summer. A recent park district bond referendum paid to upgrade the existing pool to Olympic size and to make other improvements.

Park commissioners in DeKalb are chosen in April about the time of the school board elections. There is substantial competition for the posts, although candidates generally do not represent the "elite" of the community. Rather, they are people who have been active in recreational or park activities.

Illinois has about 40 per cent of all the park districts in the United States. The approximate 300 Illinois park districts are distributed among 70 of the state's 102 counties. They were originally created to avoid municipal tax limits and to provide more generously for park and recreation services, although this advantage is no longer a factor in home rule cities since the 1970 Constitution.

Park districts have very complex boundaries often covering many other jurisdictions. Many are "defensive" governmental units which were created to protect the original residents, especially in rural areas, from being subject to larger districts with higher service levels and taxes.

| Park districts and municipalities often have disputes over policies. A common disagreement is over police patrol of parks. Although districts may hire rangers, many smaller districts prefer to ask the municipality to patrol. Aside from out-of-pocket costs, municipal police patrol of parks is a problem |  |

September 1977 / Illinois Issues / 23

|

|

when only part of the park is in the city, and the police regard the extra patrol as a benefit to nonresidents of the city. Another potentially controversial area involves municipal zoning and building controls. Some districts insist that as sovereign units they have the power to adopt their own construction codes for pools or maintenance buildings and that municipal zoning does not apply to park and playground sites. This is rather an explosive issue, since few municipalities are about to give up their building/zoning prerogatives. |

A subtler issue that often pits park districts against municipal councils involves priorities. Governed by advocates for sports or open space, the districts tend to resent any subordination of park or recreation functions to a set of municipal priorities.

Besides park and sanitary districts, the four other most common types of special districts are housing, fire protection, drainage and soil and water conservation. Some levy taxes directly; others are funded from general county, state or federal revenues.

Fire protection districts

The 1927 act (Illinois Revised Statutes, 1975, Chapter 127I1/2 sections 21 et al) enabling special fire districts to be created in the state allows areas outside a city to contract as a district with a municipality for fire protection services. The fire protection district can also buy its own equipment (on the installment plan or by issuing bonds) and provide services directly to the district's residents.

Smaller districts may maintain limited facilities and a volunteer force but depend upon mutual aid agreements in the event of an excessive demand upon their resources because of large fires or many fires at once. District trustees are usually long-tenured and may also be members of other local special district boards. Presently, all the land in DeKalb County is contained within one of 19 fire districts, a number of which cross county lines. In the state, there are over 700 fire protection districts. These have proliferated in recent years as areas attempt to avoid annexation by municipalities which provide fire protection. DeKalb's fire protection district was created in 1967 as a response to the tactics of surrounding communities trying to expand their tax bases. (The attempt by Sycamore's fire district to expand southward in 1963 was thwarted because the district tried to include property owned by the president of the DeKalb community fire association, an influential figure in local politics.)

One of the results of this "defensive" method of creating boundaries has been the somewhat unequal distribution of services. Boundaries are not determined by efficiency criteria, such as the distance from the fire station, although expansion of a district may influence the location of additional stations. Illinois lacks county coordinating offices for fire protection, which may be needed to allocate resources more rationally.

|

Drainage districts Drainage districts are the most numerous in DeKalb County, but of the 33 districts listed in court records, only 14 can be classified as even minimally active. Many were formed around the turn of the century under the original 1879 statutes which provided for drainage districts based on a system of assessments which permitted districts to include only lands benefited. They were formed to deal with inadequacies of the common laws of natural drainage and to give landowners a means of securing proper drainage. The most recent revision of the drainage code, effective in 1956, has not changed the basic assumptions or ways of operation. |

|

DeKalb's typical active district has an annual assessment of about $4,000 for legal fees and minor maintenance operations. The commissioners are long-tenured and are elected with minimal voter participation. Unlike other special districts, drainage districts may

24 / September 1977 / Illinois Issues

and do overlap but may not share boundaries with any other governmental unit. In DeKalb, they range in size from 700 to 7,800 acres.

On occasion, districts have become embroiled in extended litigation over alleged benefits or damages. Heavy legal fees are about the only outcome of such litigation. There has been renewed activity in recent years because of the deterioration of the old tile lines, and new commissioners have been appointed to conduct surveys.

Soil and water conservation

Soil and water conservation districts are usually organized along county lines.They have no taxing powers as such and provide free technical assistance to participating landowners who must, however, pay for any improvements made upon their property. Subdistricts, established for flood control, may levy a property tax and other assessments for construction, operation and maintenance of flood control structures. Operating funds for districts come from the county, the state, the local farm bureau and other miscellaneous sources. DeKalb's soil and water conservation district budget for fiscal year 1975 was only $14,565.

The district relies greatly upon federal technical assistance from the U.S. Soil Conservation Service (SCS) and cooperates with numerous other federal and state agencies. However, the SCS acts only in an advisory capacity; the district board of directors actually sets priorities for the federal technicians. The district attempts to induce landowners to sign up as voluntary "cooperators" in order to establish their eligibility for free technical assistance.

|

District directors are elected at the annual meeting in the winter for two-year terms. They are responsible for establishing policies, priorities and the budget. They appoint associate directors for one-year terms to serve on various committees. The associate directors have served as a source of replacement for directors in the past. Directors in the DeKalb district have included a park ranger, numerous farmers, a landfill owner, a specialist in farm management and a former county planner.

The DeKalb district officially includes all the land within the county except for the municipalities incorporated at the time of its creation in 1946. All petitions for zoning variances in the district must be examined and evaluated at the petitioner's expense before being ruled upon by the particular zoning board. While this has potential for land use control, the soil conservation district must rely upon the appropriate government for enforcement, since the district does not have enforcement powers. Presently, only the City of DeKalb and the county have agreed to cooperate in this matter. |

|

Housing

Housing authorities in Illinois were created by legislation passed in 1934, enabling municipalities, counties or incorporated townships to address the problem of unsafe, unsanitary or insufficient housing. Housing authorities can be created by resolution of the municipal, county or township governing body, petition of 1 per cent of the residents, or by an order from the State Housing Board (SHB). There is a strong statutory connection between the local authorities and the state, because the SHB must approve the creation of such authorities as well as the appointments of commissioners made by the presiding officer of the appropriate governing body (township, municipality or county). The state must also approve any expenditures in excess of $2,500.

As a municipal corporation, a housing authority can issue bonds to finance construction projects. But, it does not

have any taxing powers. The general public pays for housing authorities indirectly through general state and federal revenues. While each authority can legally set its own income eligibility requirements for tenants, other criteria may be required to qualify for funds from the state or federal governments. Operating revenues, including payments to local governments for services (which can be negotiated but cannot exceed normal property taxes) are raised through rent paid by tenants.

DeKalb's County Housing Authority maintains three sites and is building a fourth. The present capacity is 225 units in two locations for the elderly (62 years and over) or disabled residents, and 26 units in a third location for families with children. Two of the present five commissioners are realtors; the third is a bank officer. Data on occupations of the other two was not available.

The fiscal impact

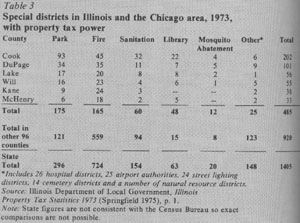

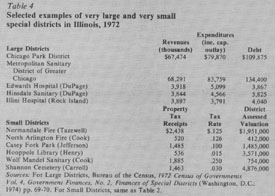

Illinois special districts have a substantial impact on the local government sector. In 1973, 10.5 per cent of all property taxes levied were by special districts, and nearly half of that was by park districts. The share of total local spending is even greater (11.5 per cent) when one counts other revenues. Table 2 indicates that district spending tends to be concentrated in specific functional areas, such as parks and sewerage, and is a very substantial portion of the total spending. Nearly 80 per cent of local

September 1977 / Illinois Issues / 25

spending for housing and parks is made by special districts. Most of these totals come from the very large districts. There were 44 districts in Illinois in 1971-72 with revenues or expenditures over $1.5 million or debt over $10 million. These "giant" districts made up about 80 per cent of total district revenue and indebtedness. Table 3 contrasts finances of very large and very small districts. Illinois, with the most special districts in the nation, ranks fifth in the number of large districts and second in total revenue among the 50 states. Only five other states, Nebraska, Washington, Georgia, Pennsylvania and Arizona, spend a higher percentage than the Illinois total of 11.5 per cent as a share of total local spending. Once one leaves the "giant" districts, the fiscal impact begins to fall off rather quickly.

If one is to believe their detractors, special districts in Illinois are increasing at a never-ending pace. In the 10 years prior to 1972, a total of 281 districts were created. However, this is only a 13 per cent growth compared to the national figure of 29 per cent during the same period. Furthermore, although Illinois districts spend a good deal of local money, the total share of local expeditures dropped from 15 to 11.5 per cent during the same 10 years. Park and sanitary districts, which primarily serve fringe or urban areas, are on the increase, while rural districts such as drainage or soil and water conservation are decreasing in number.

Why districts exist

Why do special districts survive and multiply? A major reason is that they have more flexibility to meet geographic problems. A drainage or sewage district has to meet natural topographic features, and political boundaries are highly irrelevant to service needs. To provide this service, these special districts must be created to overlap boundaries of municipalities and counties since the county or municipality cannot vary its tax rate to meet geographic needs. Although the 1970 Illinois Constitution permits varying tax rates for special service regions in counties, this has had little affect on existing districts since counties have not done much with their new authority.

Historically, state limitations on local property tax levies have resulted in attempts by local interests or local governments to "spin off a function such as parks from the general purpose unit. The resulting special district has its own tax level which is not charged to the preexisting unit. "Spinning off is also a way for municipalities to avoid the onus of tax increases.

Citizens or special interests not in a municipality may need a special kind of service but do not want the full range of municipal services they would receive by annexation to a nearby city. Sometimes those served by a special district do not want to see the specific function of the district swallowed up by a larger unit, where it might not get the "loving care" that is possible from a separately selected board for a special district.

Although it is often charged that small districts are too small to be

|

efficient, some empirical studies have shown that citizen satisfaction is higher with smaller units and that the smaller units have lower per unit costs than nearby cities. This is because the units tend to hire lower paid employees, primarily because a lower level of service is required. The efficiency argument also overlooks the wide range of cooperative arrangements that exist. Many, if not most, park districts have joint purchasing agreements with municipalities or other districts and often share equipment. Fire protection districts have mutual aid arrangements and often exist only as separate taxing units staffed by volunteers. |

Another charge is that special districts are particularly vulnerable to domination by a single interest group or even a single family. Sometimes the chief beneficiaries of small districts are lawyers, engineers and suppliers of materials. Yet the opportunity for citizens to become more active and stop such abuses is open. They can take the trouble to vote in special district elec tions, or — if the special district officers is appointed by the county board can make their power felt by the board on election day. (Before the 1970 constitution, officers of special districts were appointed by the judiciary; this was prohibited by Article VII, section 8 .) More people have an opportunity to participate in a system with many small districts than would be possible in a more centralized system.

Improving special districts

There should be better financial reporting and public information on the activities of districts. This criticism is

not limited to special districts; many small municipalities have virtually nonexistent records — financial or otherwise. The county treasurer could serve as district treasurer and chief

financial officer for most districts, investing monies through a pool. This is already required for drainage districts. The treasurer or someone else could assure that each district publishes a financial report.

Local boundary agencies are needed, ¦ particularly in urban and fringe counties, to allocate responsibilities and boundaries among local units. Patterned after models in California, Oregon and Minnesota, these agencies should be made up of local officials within the county — either elected or appointed ex officio. Their power — subject, of course, to a vote by the citizens — would include approving or denying incorporations of new units; approving annexations to any unit and ordering the creation of county taxing areas in lieu of district formation. By keeping the agency locally selected, the tendency for local units to run to Springfield for guidance might be reduced.

One should not necessarily expect high levels of voter participation in special districts, but better publicity and required open reports might encourage more citizens to be active. Districts should be required to appoint formal citizens advisory committees to publish and disseminate annual reports and audits. Citizens should not be allowed to serve on more than one board. Greater citizen involvement in special districts would solve many of the problems emphasize the strengths of this peculiarly American system.

26 / September 1977 / Illinois Issues