By JAMES H. KLEIN

An assistant professor of political

science at Loyola University of Chicago,

he is also an attorney specializing in

election law.

The author wishes to acknowledge the

assistance of Lee Norrgard, executive

director of Cowman Cause of Illinois, in

retrieving the data from reports filed with

the State Board of Elections.

WATERGATE produced more than the downfall of a president and the jailing of an attorney general. It also sparked widespread attempts to curb abuses at federal, state and local levels, abuses like those which occurred in the national election of 1972. More and more attention has been given to the connection between money and politics in the conduct of campaigns for public office. Between 1972 and 1976, new campaign finance laws were enacted by Congress and 49 states. These ranged from rules requiring disclosure of political finances to some modest experiments with public funding for political campaigns combined with limits on campaign expenditures.

In September of 1974, the Illinois General Assembly passed the Campaign Financing Act (Public Act 78-1183). It requires candidates and certain political committees, who receive or spend over $ 1,000 a year, to report contributions to the State Board of Elections. Several reports are required. Candidates must file annual reports, 30-day reports and 60-day reports. The annual report is filed in July and covers contributions and expenditures for the preceding 12-month period. The 30-day report is filed a few weeks before an election and covers contributions, but not all expenditures, for the period since the last report. The 60-day report is filed three months after an election and covers contributions for the period from 30 days before to 60 days after the election. Special reports must be filed for large contributions made during the month before an election.

The usual rationale for this complex reporting system is to discourage illegality or other abuses in the spending and raising of political money. The threat of public exposure is thought to be an effective deterrent. The reports also provide valuable information about the costs of democratic elections and the role that money plays (in conjunction with other variables) in getting and staying elected. Finally, the reports reveal the network of financially based obligations and pressures that politicians work under, given the dependence of our electoral system on private wealth.

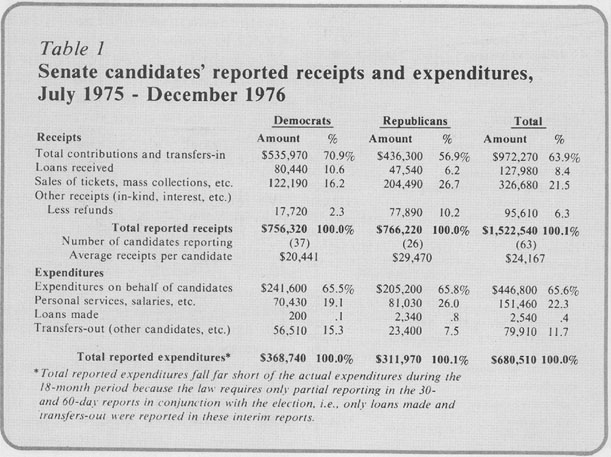

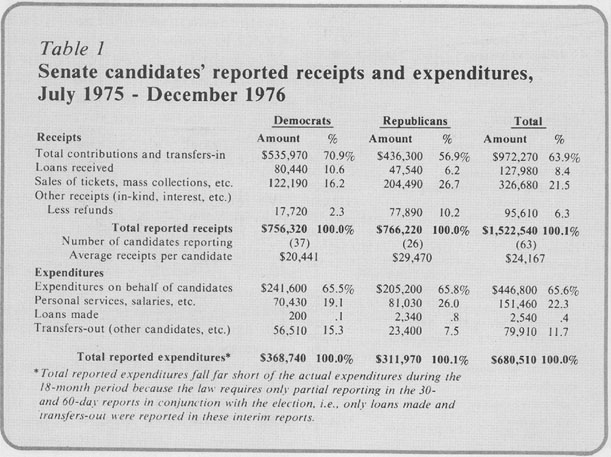

Running for the Senate is not a poor person's game: 63 candidates raised over $1.5 million, or about $24,000 each, competing for a job that pays a $20,000 annual salary

While reform has slowed as the fallout from Watergate has settled, it has by no means ceased. Congress appears ready to enact some form of public financing for congressional general election campaigns, and advocates are pushing for its extension to primaries. In Illinois, Common Cause seeks revision of the disclosure law to produce fuller and more detailed disclosure of the sources of campaign finances. Legislation has been introduced into the General Assembly that would implement public financing of statewide campaigns.

A starting point for assessment of this reform activity should be a more; complete understanding of campaign finance under the status quo. In 1976 and early 1977, several political committees filed disclosure statements on behalf of candidates running for the Illinois Senate in November 1976. A good picture of the role money plays in the election of state legislators can be drawn by looking at these three sets of reports: the annual report covering the period July 1, 1975, through June 30, 1976; the 30-day report covering the period from July 1, 1976, through the thirtieth day before the November 2 election, and the 60-day report for the period from the thirtieth day before through the sixtieth day after the election. Unfortunately, expenditure: data for the period is incomplete because full reporting of expenditures is required only in the annual report and not the interim reports. The expenditures summarized in this article occurred for the most part during the period ending June 30, 1976. Consequently, they pertain mostly to the primary rather than the general election campaigns.

Seventy-seven candidates ran for 40 seats in the Senate in the November election. Reports were filed on behalf of 63. Presumably, the 14 candidates who did not file neither accepted contributions nor made expenditures over $1,000 duringany 12-month period and, therefore, were exempted from the filing requirement. The reports clearly show that running for the Senate is not a poor person's game. Sixty-three candidates raised over $1.5 million, or about $24,000 each, competing for a job that pays $20,000 a year in salary. While Republicans raised a total only slightly higher than Democrats, the average Republican candidate raised one-and-a-

4 / November 1977 / Illinois Issues

half times as much as the average Democrat ($29,470 v. $20.441).

Table1 indicates that while most money came in the form of direct contributions from individuals and groups or transfers-in from other candidates and politscal committees. over a fifth was generated by such traditional methods as testimonial dinners, cocktail parties, ticket sales and mass collections. A surprising amount. nearly a tenth, came in the form of loans, much of it from banks. Democrats relied more heavily on direct contributions, and Republicans were more successful with ticket sales, etc.

While expenditure data for the 18-month period is incomplete, it is likely that all of the reported receipts, if not more, were spent in the course of the campaigns. Almost half of it appears to have been spent in the March primaries or during the period ending four months before the general election was held. It appears, then. that reported receipts provide a good idea of the cost of running for the Illinois Senate in 1976.

Campaign sources

Who pays these costs? Table 2 provides a summary answer to that ques¦ tion, and several striking tacts emerge.

First, while the chief purpose of the

reporting system is to deter abuse

through public disclosure, the actual

result of the law's operation is nondisclosure of the sources of almost half the

funds contributed. Over 45 percent

came trorn sources which were not

itemized by candidates in their reports.

The law requires that contributors be

identified only if their total contributions to the reporting committee, during

the previous twelve months, exceeded

$150. The exception permits widespread.

nondisclosure of the contributors.

This legal nondisclosure appears to be more extensive among Republicans than Democrats. The difference is open to various interpretations. Republican candidates may have been more dependent on small givers than the Democrats and, consequently, a larger proportion of their receipts fell within the legal exception. This interpretation is somewhat strengthened by the data on individual contributors who are identified. Democrats received a larger share frorn individuals who gave over $500 than Republicans, who, in turn, were more dependent on individuals giving in the $150-499 range. It is also possible that Democratic contributors were less adept at taking advantage of loopholes that may result from the law. For example. by carefully timing contributions over a four-year period, one might contribute nearly $600 to a campaign and still remain unidentified. This amount could be even greater if contributions were made to different campaign committees organized on behalf of a single candidate,

A second striking fact is the relatively heavy dependence of candidates on contributions from organizations and interest groups. Interest group money accounts for over a quarter of the overall total, about a fifth of the Republican total and over a third of the Democratic receipts. Illinois legislators appear to be more dependent on interest group money than members of Congress since only about 17 percent of the campaign funds for the 1974 congressional elections came from interest groups. The difference may be largely due to the fact that in 1974, corporate contributions to federal candidates were illegal.

The two most important sources of interest group money are, as might be expected, business and labor. Business interests outspent labor by almost 2 to 1 in the Illinois Senate campaigns. Most of the business money went to Republicans and almost all the labor money to Democrats. The extent of candidate dependence on these traditional sources of campaign funds is better indicated by averages. Democrats on the average received $2,051 from business interests, while the Republicans were twice as dependent on business, receiving average contributions of $4,208. On the other hand, the average labor contribution to Democrats was $2,593 which dwarfed the Republican average of $61. In fact, less than a quarter of the Republicans reported receiving any labor money, while nearly all Democrats were backed by labor.

A third pattern which emerges from the reports is the relatively unimportant role which party organizations play in campaign finance. Only a ninth of the funds raised came from party coffers, although Republicans and Democrats differed considerably here. The former were three times more dependent on party organizations, receiving an average of $3,415 from Republican groups. Democrats received $1,131, on the average, from party organizations. These partisan differences may be somewhat overstated, however, since Democratic reports do no reflect the indirect but invaluable campaign assistance provided by Chicago ward organizations.

Reform argument

What does this brief look at the

campaign finances of the 1976 state

senatorial candidates suggest about

further changes in the way Illinois

November 1977 / Illinois Issues / 5

The law fails to disclose the sources of almost half the reported receipts, due primarily to the relatively high threshold for disclosing contributor identity

regulates elections? On the face of it, it would seem that reforms promoting fuller disclosure should be considered. The aim of the 1974 act is disclosure of the sources of campaign funds to deter abuse and provide voters with some idea of the interests to which candidates are beholden. Yet the law fails to disclose the sources of almost half the reported receipts. This is due primarily to the relatively high threshold for disclosing contributor identity. The federal threshold is $100 and this is for campaigns where receipts greatly exceed those of state legislative races. Nondisclosure may also result from the loophole arising from the twelve-month cumulating period of the Illinois law.

An argument against lowering the threshold and extending the time period during which contributions from one source must be cumulated is the additional bookkeeping burdens which would be imposed on harried, nonprofessional campaign staffs. Recording and reporting large numbers of small contributions would be burdensome, but the law already requires that campaign treasurers maintain separate records showing the identity of and amount given by contributors giving over $20. Since this record keeping burden has already been imposed, disclosure of the records should be only marginally burdensome. If the threshold were lowered sufficiently, shortening or abolishing altogether the cumulation period could actually lighten the bookkeeping tasks considerably. Contributions could simply be reported as they occurred.

A related argument against fuller disclosure points to the impracticality of reporting the sources of receipts from ticket sales, mass collections and other fundraisers of this type. But most of the undisclosed money came from direct contributors; less than half, or about one fifth of the total receipts, arose from unitemized sales and collections. More- over, nondisclosure of most of these funds resulted from applying the $150 reporting threshold to sales in spite of more stringent recordkeeping require- ments that the law already imposes.

Finally, one might argue that little would be gained by requiring fuller reporting. Yet if contributions running to several hundred dollars can be made from one source which remains uniden- tified and this type of contribution comprises a significant portion of some candidates' total receipts, are the deterrent and informational purposes of the law really being fully served?

Public financing

Another alternative is public financ-

ing of state elections in Illinois. The

demand for public funding usually rests

on two assumptions. First, if electoral

politics depends upon private wealth,

persons of modest means are practically

excluded from full participation, unless

they can attract wealthy supporters.

Second, by depending on outside

sources of wealth, candidates may feel

more responsible to these private

interests than to the broader interests of

their constituents. In theory, public

funding makes running for office closer

to the grasp of the common man or

woman while reducing entanglements

with "special interest" money.

While the data from the campaign reports shows the heavy dependence of Senate candidates on interest group money, this alone probably fails to justify using taxpayers' money to support political campaigns. The reports do reveal the economic inequalities among candidates, and how these inequalities limit the choices of voters. Specifically, if the money available to candidates affects their chances of success at the polls, then fundraising ability, rather than the voice of an informed electorate, determines the outcome of elections.

Common sense indicates that campaign effectiveness is partly a result of the resources available to the organization. Money buys many of those resources, particularly in an age increasingly dominated by media efforts to

Table 2

Sources of receipts reported by Senate candidates,

July 1975 - December 1976

|

|

|||||||

| Democrats | Republicans | Total | |||||

| Amount | % | Amount | % | Amount | % | ||

| Partisan groups: | |||||||

| Democratic | $ 45,250 | 6.0% | $ 0 | 0.0% | $45,250 | 3.0% | |

| Republican | 0 | 0.0 | 126,350 | 16.5 | 126,350 | 11.3 | |

| Total partisan | 45,250 | 6.0 | 126,350 | 16.5 | 171,600 | 11.3 | |

| Ideological groups | 2,780 | .4 | 4,970 | .6 | 7,750 | .5 | |

| Professional groups: | |||||||

| Education interests | 40,910 | 5.4 | 6,250 | .8 | 47,160 | 3.1 | |

| Medical interests | 18,650 | 2.5 | 19,580 | 2.6 | 38,230 | 2.5 | |

| Other professional | 6,180 | .8 | 1,950 | .3 | 8,130 | .5 | |

| Total professional | 65,740 | 8.7 | 27,780 | 3.7 | 93,520 | 6.1 | |

| Business groups: | |||||||

| Insurance interests | 1,200 | .2 | 2,450 | .3 | 3,650 | .2 | |

| Construction interests | 4,050 | .5 | 2,850 | .4 | 6,900 | .5 | |

| Real estate interests | 6,100 | .8 | 8,960 | 1.2 | 15,060 | 1.0 | |

| Transportation interests | 5,290 | .7 | 4,880 | .6 | 10,170 | .7 | |

| Banking interests (including loans) | 35,820 | 4.7 | 31,290 | 4.1 | 67,110 | 4.4 | |

| (Bank loans) | (29,000) | (25,150) | (54,150) | ||||

| Various businesses | 23.440 | 3.1 | 58,980 | 7.7 | 82,420 | 5.4 | |

| Total businesses | 75,900 | 10.0 | 109,410 | 14.3 | 185,310 | 12.2 | |

| Labor groups | 103,720 | 13.7 | 2,250 | .3 | 105,970 | 6.9 | |

| Law firms | 11,500 | 1,5 | 1,810 | .2 | 13,310 | .9 | |

| Individuals: | |||||||

| Registered lobbyists | 200 | * | 950 | .1 | 1,150 | * | |

| Individuals.giving $500 or more | 40,310 | 5.3 | 25,520 | 3.3 | 65,830 | 4.3 | |

| Individuals giving $150 - S499 | 47,860 | 6.3 | 62,860 | 8.2 | 110,720 | 7.3 | |

| Candidate to self (including loans) | 50,090 | 6.6 | 28,160 | 3.7 | 78,250 | 5.1 | |

| (Self loans) | (44,480) | (20,890) | 65,370 | ||||

| Total individuals | 138,460 | 18.2 | 117,490 | 15.3 | 255,950 | 16.7 | |

| Miscellaneous sources | 840 | .1 | 2,290 | .3 | 3,130 | .2 | |

| Unidentified sources | 312,130 | 41.3 | 373,870 | 48.8 | 686,000 | 45.1 | |

| Total receipts | $756,320 | 99.9% | $766,220 | 100.0% | $1,522,540 | 99.9% | |

| *Less than .1% |

|

|

influence voters. The reports filed by candidates for the Senate support common sense. Winners reported average contributions of $27,428 while the average loser reported having only $19,527 to spend. This 3 to 2 advantage of winners is probably closer to 2 to 1 when those candidates not filing reports are taken into account, if one assumes that nonfilers raised under $1,000. Only three winners were nonfilers in contrast to eleven losers, which significantly increases the spread between the contributions of winners and losers.

Incumbent advantage |

A factor that is frequently singled out as crucial in deciding elections is incumbency. Incumbent state senators who ran in 1976 were reelected at the rate of 93 per cent. Because of their electoral advantages, incumbents are prime beneficiaries of smart money betting on winners. The drawing power of incumbents is well demonstrated in the reports. Incumbents with challengers raised an average of $37,511 in contrast with their challengers' average of $20,012. Not only are challengers faced with a disability in terms of raising money, but they face another handicap. In order to overcome the electoral advantage of an incumbent opponent, a challenger must raise considerably more money to win than the incumbent. Victorious incumbents in contested elections raised an average of $26,926, while victorious challengers raised $45,735 on the average. Challengers who beat incumbents engaged in intense scrambles for funds which were necessary not only to counteract the "natural" advantages of incumbency, such as greater visibility and established staff, but to counteract the incredible fundraising power of incumbents threatened by defeat. Defeated incumbents raised an average of $54,880 in their attempts to stave off their opposition. The one consoling fact that emerges from this pattern of escalation is that these successful challengers, although out-spent by powerful opponents, prevailed at the polls. But these are exceptions to the general rule that incumbents usually are reelected. The relationship between money and victory is further born out in contests pitting two nonincumbents for an open seat. Winners outraise losers at better than 3 to 2.

|

There are, however, other patterns in the data which suggest that it is an oversimplification to stress the advantages of incumbents over challengers as a starting point for thinking about ways of reforming the system of financing elections. A more complex yet more revealing explanation may depend on the political experience of a candidate rather than simply on incumbency. This approach is suggested by the fact that one group of nonincumbents actually reported raising considerably more than incumbents. When nonincumbents are broken down into two groups — those holding no public office immediately prior to the election and those holding some elective or appointive office other than a Senate seat — officeholders report raising an average of $32,097, or nearly $4,000 more than incumbents on the average. By the same token, average contributions to nonofficeholders drop dramatically to $12,586. In other words, while challengers lacking much political experience are severely handicapped in their ability to raise the cash necessary to mount an effective campaign, politically seasoned challengers appear to possess that capability. Not only is a candidate's experience directly relevant to fundraising ability, but so is the political experience of the opposition. Figure 1 illustrates what appears to be a two-fold effect on |

|

November 197 7 / Illinois Issues / 7

In close races, extremely large sums were raised —

twice as much as by big

winners, who didn't need the money, and five times as much as by big losers, who couldn't raise it

fundraising potential resulting from the nature of the opposition. For politically inexperienced candidates, the stiffer the opposition, the harder it is to raise money. The effect of seasoned opposition on experienced candidates is precisely the reverse. The tougher the fight, the more money a professional pol can and does raise. A nonincumbent candidate holding some public office is much more like an incumbent in this regard than a candidate holding no public office.

Experience factor

The explanation for this pattern

probably arises from the fact that

seasoned politicians simply are more

credible candidates than political newcomers. Having won any election, they

would appear more likely to mount an

efficient campaign, more likely to win

and more likely to be an effective

legislator. The first two of these three

perceptions are borne out by the experience of the 1976 elections. Table 3

illustrates how experienced nonincumbents were much more likely to win than

political newcomers and more likely to

win by wide margins. While incumbents

demonstrated their overall superiority,

experienced nonincumbents were more

like incumbents than neophytes in terms

of electoral effectiveness.

Furthermore, while the table also shows that the chances of winning fell as the experience of one's opponent rose, professional politicians pitted against incumbents still had a one-in-three chance of winning while newcomers had little hope. As the stiffness of the opposition increases, so does the need for money to finance an effective challenge. Seasoned politicians are able to raise the extra money because they offer reasonable odds to their backers that they are betting on a winner. Newcomers cannot match those odds.

|

Table 4 illustrates clearly the dramatic impact which the intensity of the competition and the candidates' apparent effectiveness have on fundraising potential. In closely contested races in which candidates polled 45 to 55 per cent of the votes, extremely large sums were raised — twice as much as by big winners, who didn't need the money, and five times as much as by big losers, who couldn't raise it. Seasoned challengers, in tight races, raised more than incumbents. Even newcomers raised well above the average in these close races, although they were seriously disadvantaged in comparison with the pros. That disadvantage disappears, however, in races where candidates were victorious by wide margins. Apparently, their effectiveness as candidates was perceived by contributors apart from their political inexperience, and newcomers outraised incumbents in this category. What do these patterns suggest about the need for public funding of campaigns in Illinois? If you stop after analyzing the fundraising abilities of incumbents and challengers, then public funding of legislative elections is an appealing way to give voters more meaningful choices through evenly matched contests. However, on closer examination, the situation is not so simple. Private campaign financing is widely available to nonincumbent professional politicians and relatively unavailable to amateurs. Giving public money to these nonincumbent professionals would only make them stronger. The key to political money is experience and all that it brings — exposure, know- how and credibility as a campaigner. Perhaps experience is a more defensible criterion than incumbency for determining whose campaigns are fully funded. Would it be an intelligent use of resources --- private or public — to spend $20,000 on the campaign of a politically unknown Republican in Chicago's 23rd Legislative District, trying to even up the odds in a contest with Sen. Richard M. Daley, whose failure to file any reports suggests he raised and spent less than $1,000? |

|

New approach

Without suggesting that political

experience should be the sole criterion

for financial support (obviously, no

public subsidy could depend on such a

standard) or that public financing of

campaigns is without merit, more study

of the consequences of public campaign

financing should be made where it is

already used in other states and at the

federal level. Have subsidies really

opened up the electoral process to wider

participation? Have subsidies made it

possible for nonexperienced challengers

to win or have they made it even easier

for incumbents to retain office?

If subsidies are to be seriously considered, would they be better spent in primaries rather than general elections? Since most legislative districts are dominated by one party, primaries are where the real competition takes place. Or should a completely novel approach be taken? Rather than subsidizing the most expensive campaigns for higher office, presidential, congressional, gubernatorial, legislative, etc., perhaps the real need is on the local level — the entry point for most politicians. The higher one's aspirations and the greater one's experience, the easier it is to raise money. Perhaps, then, the next item on the agenda for electoral reform should be to make it easier for people to obtain the political experience necessary for campaign fundraising and election to higher office. The scope of such reform would not only involve public subsidies to local electoral campaigns but would encompass efforts to remove a variety of barriers to fuller participation by citizens in their government. ž

8 / November 1977 / Illinois Issues