By JOYCE E. KUSTRA

Illinois Issues' special assignments

writer in the Chicago area, she

holds a master's degree in journalism.

Clickety click, clackety clack, clickety

click, clickety click, clackety clack

The RTA chugs on

|

SPARKS fly almost every time the four

suburban board members of the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA)

clash with the five Chicago members.

The nine members of the RTA's board

do not often agree on policy matters

relating to mass transportation in its

jurisdiction: the six northeastern counties of Cook, Lake, McHenry, DuPage,

Kane and Will. The suburbanites cry

foul every time the Chicago members

call for a vote, but are saved from being

defeated on every vote by the majority

Chicago members since a two-thirds

vote is required for budget approval,

taxation and certain other major items

such as condemnation of public property.

At a recent board meeting, threats

from the suburban minority were heard

after the Chicago contingent chose a

city-based firm to perform a routine

audit. "How many firms outside the city

of Chicago have been retained by the

RTA to do audits?" one suburban

member asked.

The question went unanswered, but

the message was clear: the suburbs do

not feel that they are well served by the

RTA, either in the administration or,

more importantly, in the actual services

provided by the system. They argue that

the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) is

the only company benefiting from the

formation of regional transportation

service. Chicago members counter that

considering the number of people served

and the amount of money each area

pumps into the RTA, that is not true.

The battle goes all the way back to the

days when city dwellers first discovered

the greener fields of suburbia, only to

find that they needed to get back into the

city to work. Years have passed and

many industries have moved out of

Chicago; now central city commuters

are finding it just as difficult to get to

their jobs in the suburbs. While RTA officials plan toward a comprehensive,

complete transportation system, the day

when it will become a reality for the

entire region is not close at hand. In the

meantime, the arguments are hashed

over and over again.

|

One argument not heard as loudly

these days is whether a regional system

of transportation is even necessary for

northeastern Illinois. Except for a few

die-hards in the outlying areas of the

region, there is general agreement that a

regional approach is necessary if mass

transportation is to operate successfully

in the area. At a recent meeting of

McHenry County Republicans, Gov.

James R. Thompson hinted that he

might support a move for McHenry

County to pull out of the RTA, much to

the delight of his partisan audience.

When angry responses began to pour in,

the governor backed down from the

statement.

There is also general agreement that

mass transportation can no longer

operate without government subsidies.

The cost of operating expensive equipment in an era of mushrooming fuel

prices makes it impossible for any mass

transit carrier to break even on the fares

it charges its riders. In fact, the CTA,

which carries about 2 million of the 2.5

million daily riders in the region, gets

one-third of its operating revenue from

the RTA. A final argument favoring

regional mass transit comes from the

energy shortage and the deteriorating

environmental condition. It has become

essential for a metropolitan area such as

northeastern Illinois not only to provide

sufficient mass transportation as an

alternative to automobile transportation, but also to attract as many riders as

possible for the system.

The division between RTA factions

has been there ever since the debate over

the enabling legislation took place in

Springfield back in 1973: how to divide

16 / November 1977 / Illinois Issues

ii771117.html

revenues and subsidies equitably among

the CTA, suburban bus lines and

commuter rail lines. At that time, all

three were in varying stages of financial

strife. Individually, the fragmented

transportation lines of the pre-RTAera

were in no position to secure the kind of

financial aid necessary to keep the

transit systems going. Collectively, the

transportation companies were able to

secure additional funding because of the

RTA's jurisdictional umbrella.

Genesis of the RTA

The RTA was established for several

reasons. The most important was a

consensus among RTA supporters, as

stated by Chicago board member Pas-

tora San Juan Cafferty, "Northeastern

Illinois is a tightly knit area and the

whole area stands or falls together." But

several other factors also convinced the

RTA proponents that a regional government was the only practical way to

reverse the trend of diminishing funds

and services. Each year, the General

Assembly found itself in the position of

considering deficit appropriations to

bail out private carriers to keep the

trains and buses running. This expensive and time-consuming task was one

most of the lawmakers were happy to

relinquish. Also, federal funding was

contingent on a regional approach to

mass transportation, and the federal

government required that all six northeastern Illinois counties be included to

qualify as an acceptable urbanized

region. In northeastern Illinois, the

RTA is the only designated recipient of

grants from the Urban Mass Transit

Administration (UMTA) which disburses federal monies to mass transit agencies.

The division between RTA

factions has been there

ever since the debate over

the enabling legislation

took place in Springfield

back in 1973: how to divide revenues

and subsidies equitably

In 1971 the state's new Constitution

became effective and recognized the

need to subsidize transportation; Article

XIII states that public transportation "is

an essential public purpose for which

public funds may be expended." That

same year, the CTA was experiencing its

first deficit year, so Cook County and

the city of Chicago each diverted motor

fuel tax funds to keep it going. In early

1971, Republican Gov. Richard B.

Ogilvie delivered a "Special Message on

Transportation" to the General Assembly in which he urged the lawmakers to

approve the Transportation Bond Act

allowing the use of bonds for capital

improvements for public transportation

carriers throughout the state. At the

same time, he proposed a regional

agency to deal with the huge mass

transportation network in northeastern

Illinois. After the legislature passed the

Transportation Bond Act, Ogilvie in

1972 appointed a task force which

considered the regional transportation

concept and set forth an outline of what

alternate forms the RTA might take.

Although various organizational

forms were considered for the RTA —

from total control over the lines to merely coordinating the transit systems —

the final form chosen was that of an

umbrella organization. The most important effect of this decision was that

the large CTA organization remained

intact to operate in much the same way

as before. The RTA act does include a

provision, however, which would allow

the RTA to become the actual operating

agency of the CTA. While Chicago

board members drag their feet on this

issue, their suburban colleagues keep

urging action.

Gov. Dan Walker succeeded Ogilvie

in 1973, the year the legislature tackled

the job of drawing up the Regional

Transportation Act. The session came

and went with a thorough airing of the

proposed RTA but with no action. It

was not until Walker, legislative leaders

and representatives of Chicago Mayor

Richard J. Daley caucused in November

of 1973 that differences were ironed out:

the Regional Transportation Act was

passed by the ensuing Third Special

Session of the legislature and would

become effective in December 1973.

Meanwhile, short-term stopgap relief

had to be provided to keep the wheels

rolling in northeastern Illinois. Some

observers feel that theseveral financial

crises in transportation were deliberately caused by legislative leaders who

held down funding levels in order to

bring the RTA to fruition.

Referendum

The RTA enabling legislation called

for the controversial act to be put before

the voters, even though there were some

proponents who felt the referendum was

unnecessary and unwise. They felt the

highly spirited campaign and election

would only polarize opinion on the

subject rather than appease dissidents;

other RTA backers felt the referendum

would help solidify support. The RTA

Citizens Committee was formed to sell

the idea to the voters, but the committee's efforts were countered by suburban

legislators who campaigned against the

RTA, The final vote count, listed in

table 1, showed overwhelming suburban

Table 1

Unofficial vote count

on RTA referendum

|

County

|

Support % Oppose %

|

|

McHenry

|

: 2,777 9 27,533 91

|

|

Kane

|

5,865 11 46,187 89

|

|

Will

|

5,995 11 45,298 89

|

|

Lake

|

16,981 25 48,621 75

|

|

DuPage

|

27,224 25 79,821 75

|

|

Cook

|

|

|

(outside Chicago)

|

168,949 41 234,788 59

|

|

Cook

|

|

|

(inside Chicago)

|

456,475 71 189,039 29

|

|

Totals

|

684,266 50.5 671,287 49.5

|

|

|

|

rejection, but Chicago — the only place

where the referendum carried — had

such a heavy turnout that its votes

pushed the RTA over the top by a mere

13,000-vote margin, and the proposition

became law. Court challenges followed,

but in the end the vote stood, and

regional transportation became a reality

for northeastern Illinois.

Provisions of the act

The act stipulates that the RTA

coordinate transportation planning in

the six-county region and have authority to control public transportation service in the area. The act also

specifies RTA as the governmental unit

entitled to receive state and federal

grants and loans and sets its jurisdiction

over 250 communities as well as the city

of Chicago. While the RTA does not

actually control Chicago's CTA operations (the CTA operates under its own

board), it does control CTA's purse

November I977 / Illinois Issues / 17

ii771118.html

strings to a large extent, providing

about one-third of its operating budget.

The RTA Board of Directors has

often been more controversial than the

actual delivery of mass transit services.

The act calls for a nine-member board: four appointed by the mayor of Chicago

and approved by the City Council; two

appointed by the six suburban members

of the Cook County Board; two appointed by the chairmen of the five

collar county boards; and one, the

chairman, chosen by the other eight

members. Originally, the chairman also

served as chief administrative officer.

However, in 1976 Chairman Milton

Pikarsky became the chief target of

complaints made by suburban directors,

who charged he was a poor administrator and that he acted unfairly toward

suburban transit lines. They demanded

his resignation. The resulting compromise, in which the suburban members

won several concessions, also called for

the hiring of a chief operating officer,

thus diminishing the chairman's power.

|

|

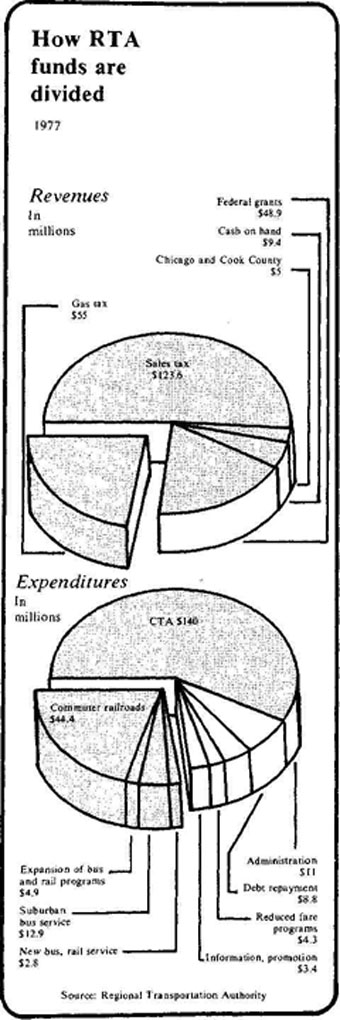

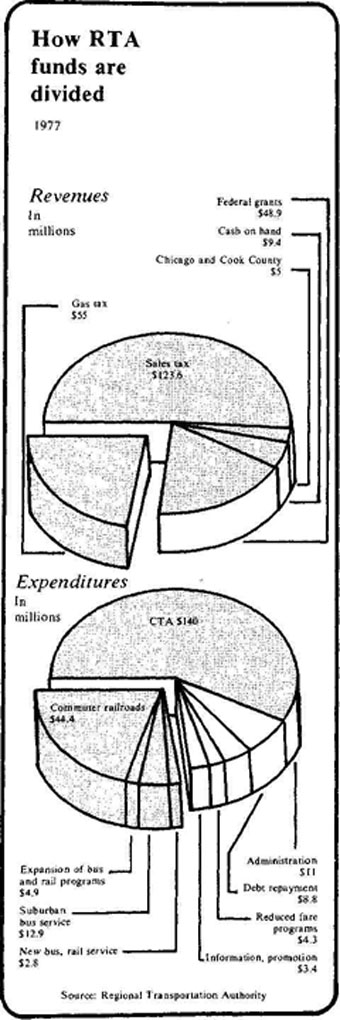

Financing the RTA

RTA proponents like to point out

that no new taxes were levied to create

the RTA; funds were simply diverted

from existing revenue sources. But that

changed this year. The act originally

allowed for revenues to flow into the

RTA from the state's Public Transportation Fund. The fund collected its

monies from four sources: (1) 3/32 of

the state sales tax collected in the six-

county region; (2) $14 of each motor

vehicle license fee collected in the city of

Chicago; (3) a $5 million annual contribution from Chicago and Cook County; (4) federal UMTA funds for both capital

improvements and operating purposes.

Before the RTA Board of Directors

could pass the fiscal year 1978 budget

last spring, they approved a fifth source

of revenue, a 5 per cent gasoline tax for

the six-county region. The flat 5 per cent

tax proposed by Chicago members was

chosen over a suburban proposal calling

for a differential tax, which would have

ranged from possibly no levy at all in

outlying McHenry County to the maximum allowed of 5 per cent in Chicago.

But, several RTA officials argued that a

differential tax would be declared

unconstitutional, and the time lapse

involved in a court struggle would mean

the loss of badly needed funds and

possibly create a critical deficit. The Chicago measure prevailed.

Estimated to generate $70 to $80

million a year, the gas tax was seen by

Chicago board members as the only

solution to the problem of a $55 million

deficit in the $237 million budget for

fiscal 1978, especially since the General

Assembly had rejected an RTA request

for authorization to levy a one-cent sales

tax. With the exception of one suburban

board member, the gas tax measure

failed to receive support from suburban

members who argued that the new

revenues would simply reinforce already existing inequities. Although the gas tax

plan calls for the revenue to be returned

to the area from which it comes,

suburban members are unimpressed

and still fear that suburban revenues will

end up subsidizing CTA operations.

The lone suburban supporter of the

gas tax, Daniel Baldino of Evanston,

went along reluctantly after extracting

some concessions from the majority,

including an extra $5 million for

suburban lines and changes in the

formula which distributes bond and

federal grant money to make distribution more favorable to the suburbs.

Baldino also demanded an expiration

date for the gas tax of October 1979 so

the new tax could be evaluated to see if

the RTA commitment to expand suburban service is genuine. A two-thirds

majority will be required to extend the

tax.

New and expanded services will not

be an easy promise to keep. Even with

the gas tax, some observers estimate

that the agency will face another

multimillion dollar deficit by 1980. The

five-year plan prepared by the RTA

indicates that any deficit might be met

by fare increases of about 20 percent, or

10 cents on bus and rapid transit lines.

The plan indicates that fare increases

would be "in keeping with a philosophy

of sharing the costs of public transportation between the direct user and the

general public," but it is a solution

which would run counter to the RTA's

goal of stabilizing fare levels. The other

alternative to avoid a deficit would

mean another trip to Springfield to ask

for new taxing authorization, perhaps

another try for a one-cent sales tax.

The RTA five-year plan is necessarily

sketchy and subject to change, but it

does show that the RTA's financial woes

are far from over. It also raises the

question of how new transit lines will

ever reach the suburbs in the proportions that are being demanded by

commuters and their representatives on

the board. Figures indicate that the

financial crunch will continue and that

new programs will probably be shelved

so that existing lines can continue to

run. Of the existing lines, studies show

that the CTA actually performs much

more efficiently than other services in

the region. The amount of subsidy per

passenger for the CTA is far below that

of both commuter railroads and suburban bus lines. However, basing subsidy

levels on current ridership naturally

|

18 / November 1977 / Illinois Issues

II771119.HTML

favors established systems at the expense of new systems,

Current budget

Of the $237 million operating budget

for fiscal 1978, $198 million goes to

subsidize transit lines. New services,

mostly in the suburbs, are budgeted for

nearly $17 million. The rest is for

administration, advertising and debt

repayment. About 71 per cent of the

subsidies, or $141 million, will go to the

CTA, which serves Chicago plus 22

suburban communities and carries over

80 per cent of the region's commuters.

The CTA subsidy plus the $57 million

subsidy for suburban bus lines and

commuter railroads represent a 23 per

cent increase over last year's budget. A

$304 million capital program is anticipated with most of the funds coming in

the form of federal grants. About one-

third of this amount will go toward the

replacement of 300 CTA rapid transit

cars, most of which have long outlasted

their expected use. New buses and

railroad cars plus maintenance are also

included in this capital expenditure.

This high cost of maintaining and

replacing existing equipment and facilities allows little extra for expansion in

the capital program.

Conclusion

In its March 1977 Report (majority)

to the General Assembly, the Legislative

Advisory Committee to the Regional

Transportation Authority listed six

areas of progress since the RTA's

implementation. The first was area

involvement, and the committee reported that the RTA now serves 120 of

the 251 municipalities in the region and

that includes 83 per cent of the population in the six-county area. The implementation of a standardized fare structure in the region was also noted in the

report: whereas fares previously varied

widely from one carrier to another, a

standard 50-cent fare is now charged for

all bus and rapid transit trains in

Chicago and most Cook County suburbs while 30 cents has become standard

for many smaller local bus systems. A

universal transfer system is also being

implemented to simplify changing from

one system to another. The process of

standardizing the more expensive commuter train fares is in progress, with a

new zone system to determine a passenger's fare which would result in all lines

charging the same fare for the same

distance traveled.

The committee also pointed to four

more accomplishments of the RTA's

formative years: (1) reduced fares for the

elderly and handicapped; (2) an around-

the-clock Travel Information Center in

several languages which was a CTA

service taken over by the RTA; (3)

service agreements with all seven railroad lines serving the region which

assures coordinated transportation

delivery; and (4) a major program to replace antiquated equipment.

Chicago's expressways have helped to

create the burgeoning suburbs which

surround the central city. While the

expressway system has provided the

mobility necessary for the central city

resident to move to suburbia, that

development in itself has caused its own

set of problems: those same suburbanites must get back to their jobs. In

northeastern Illinois, the automobile

and the expressways on which the

automobile is dependent threaten to

(Please turn page)

November 1977 / Illinois Issues / 19

But mass transportation

must succeed in the Chicago

area, as it must in every

other metropolitan area.

It must be made available

suffocate the area with polluted air and

to strangle it with massive traffic jams.

Urban planners and transportation

experts agree that the only way to relieve

traffic congestion and insure the economic vitality of the city is to move

the automobiles off the expressways

and the commuters onto the trains and

buses of the RTA.

There are a number of political and

economic obstacles, however, that lie in

the path of an effective public transportation system for the Chicago area.

Disgruntled counties want to pull out, a

move that some feel would cripple the

whole system. The handicapped cry for

facilities which would allow them easier

access to mass transit, a laudable goal

but one with a high price tag. Commuters can't be convinced to leave their cars

at home and take the bus, in spite of a

flashy media campaign by the RTA. The

nine RTA board members seem to agree

on little (one recent argument concerned

whether six-year-olds were old enough

to travel alone). And worst of all, there's

never enough money; mass transit just

cannot pay for itself.

But mass transportation must succeed in the Chicago area, as it must in

every other metropolitan area. It must

be made available to as many people as

possible and people must be persuaded

to ride. To cut air pollution and save

energy, there must be less dependence

on the automobile. Mass transit offers

the only reasonable alternative.

The RTA has come through its

formative years with a few scars but no

mortal wounds. But there has been no

dramatic increase in ridership since 1974

when the agency began operations, and

attracting new commuters remains the

number one goal. As the suburbs

continue to- grow around the political

and economic hub of Chicago, a regional transportation plan will become more

and more important. The Regional

Transportation Authority, created by

state law and endorsed by the federal

government, is and will continue to be

the agency designated to provide that

plan. ž

20 / November 1977 / Illinois Issues