|

By DONA P. GERSON

A member of the Evanston Zoning

Board of Appeals, she is administrative

assistant to Commissioner Joanne Alter,

Chicago Metropolitan Sanitary District.

Inflation of property values

combined with increased tax levies

Tax revolt in Cook County

WHEN 1976 real estate tax bills arrived

in the summer of 1977, howls of protest

rose from the homeowners in the

recently reassessed north quadrant of

Cook County. Hundreds of people

came to hastily arranged protest meetings, exchanged horror stories of whopping tax increases and listened to long

explanations of assessment, equalization and levies. They puzzled over

proposals of elected officials, found

little help from the leaders of the tax

protest group and in the end cursed

government, politicians, rotten luck and

went home and paid their taxes.

Property taxes are and have been the

major source of tax revenue for local

governments. They are raised locally

and spent locally. Over two billion

dollars in property taxes were levied in

Cook County in 1976. Over half this

amount was levied on property in

Chicago by seven major taxing bodies:

City of Chicago, Chicago Board of

Education, City Colleges of Chicago,

Chicago Park District, Cook County

Forest Preserve District, Metropolitan

Sanitary District of Greater Chicago,

and Cook County. Slightly less than one

billion in taxes were levied on property

outside of Chicago by 125 cities and

villages, 149 school districts and 10

junior college districts, 94 park districts,

30 townships, 36 library districts, 11

other taxing districts (fire protection,

public health, mental health and others)

along with Cook County, Forest Preserve District and the Metropolitan

Sanitary District.

Cook County, the state of Illinois,

and the 560 tax levying governmental

units are all involved in the determination of property taxes of the 1.3 million

parcels of property in Cook County

through assessment, equalization and

the levying of taxes.

Property taxes have a bad reputation.

No one likes them and yet they endure.

But in 1977 the combination of inflation

of property values and increased tax

levies stunned the reassessed homeowners of Cook County.

Cook County reassesses one-fourth

of the property each year. Before the

north quadrant was reassessed, Cook

County Assessor Tom Tully proposed

that the Cook County Board reduce the

rate of assessment of single family

residences from 22 to 16 percent of fair

market value.* In support of the lower

assessment rate, Tully cited sharp

inflation of value of single family

residences and noted that assessment

was now keyed to market value.

The proposal met with a mixed

response. Some taxpayers groups supported it, but school and park districts

with tax rate limits strongly opposed it.

Dr. Wesley Gibbs of Niles Township

High School said that by changing

assessment levels the Cook County

assessor would become a third force in

local-state development of school policy. Other administrators described

deficit spending and fears of a reduced

tax base. Tully pledged that no township would receive a decreased assessed

valuation.

With Tully predicting soaring assessment levels unless the rate for single

family residences was reduced, and the

the school and park boards fearing dire

consequences unless the rate was maintained, Cook County Board President

George Dunne said, "The Cook County

Board of Commissioners is placed in a

very uncomfortable position. In the case

of this proposal, we're damned if we do,

and damned if we don't." They opted for

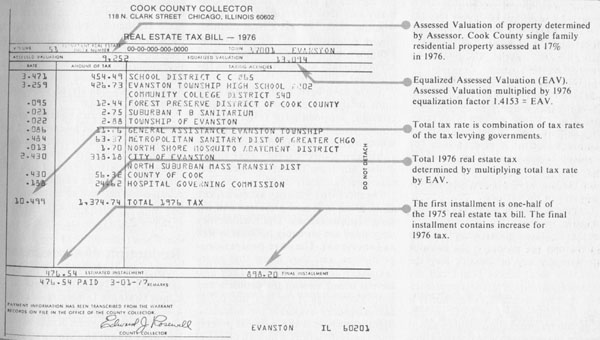

"damned if we do" and voted a compromise 17 per cent rate of assessment for

single family residences. Tully was

pleased, the school districts were nervous and almost all of the taxpayers

were unaware of the drama that was

played out in the County Building.

The reduction in the rate of assessment did not reduce assessed valuation

because inflation was greater than the

reduction. The median value of one-family owner occupied homes in

Chicago Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area rose 60 per cent from 1970 to

1975 according to the U.S. Bureau of the

Census Annual Housing Survey of

Chicago for 1975. Reassessment of the

north quadrant of Cook County led to

an increase of 14.6 per cent of assessed

valuation.

While taxpayers received reassessment notices, they did not know how

reassessment might affect their tax bills.

An increase in the assessed value of

property does not in itself increase the

tax bill. If the amount of money to be

raised by property taxes (levies) remains

constant, the tax bill will be constant,

regardless of the assessed valuation.

But tax levies in suburban taxing

districts did not remain constant. (The

City of Chicago's levy was essentially

unchanged.) Levies of suburban municipalities increased more than 7 per cent

over the previous year. Financially

strapped school and park districts held

referenda to increase their tax rates, and

suburban elementary school levies rose

almost 14 per cent, high schools 7 per

cent and park districts almost 19 per

cent.

Increased levies by local governments

* The 1970 Constitution allows Cook County to classify

real properly for tax purposes provided that the level of

assessment of the highest class is not more than 2 1/2 times

the lowest class (Article IX, section 4 (b)). With

commercial/ industrial property assessed at 40 per cent of

fair market value, 16 per cent was the lowest possible rate

for single family residential properly or Class II, which

includes houses, condominiums, co-ops and small

apartment buildings with six units or less.

4/ January 1978/ Illinois Issues

and increased rates as the result of

referenda led to higher tax rates. Higher

rates multiplied by the higher assessed

valuation meant much higher tax bills.

When the tax bills were mailed out

and the dust settled, the impact of higher

taxes hit full force. The shock registered

very high on the taxpayers' equivalent of

the Richter scale. Some individual tax

bills in the reassessed portion of Cook

County rose 50 per cent, 100 per cent

and even more. Taxpayers were shocked

because they were unaware of the affects

of changes in assessments, unaware of

increased levies and tax rates, and

because the full increase was contained

in the second tax installment.

Changes in assessments

Because higher tax bills arrived after

the 1976 reassessment of property, the

first shots were fired at the assessor. And

there had been changes in assessment

practices, but all indications are that

these are changes for the better. The Civic Federation, a taxpayer watchdog

group, stated, "We feel that the quality

of assessment of homes for 1976 is the

best that we have had in Cook County

for many years."

Major changes in the Cook County

Assessor's Office came about after a

thorough study of that office by Real

Estate Research Corporation, which in

1971 recommended major modifications in the real property evaluation

process, including use of current information about sales and market prices

and greater uniformity in relation to

actual market values. Tully says significant changes resulted from adoption of

a new "Cost Manual" to replace the

outdated "1932 Cost Manual."

Since the 1971 report, the Assessor's

Office has new procedures, a professional staff, a computerized system, a

Classification Ordinance, and an updated Cost Manual. Current sales prices

of property are used in appraising the

value of property. These changes should

lead to assessments much closer to fair

market value. Market value based on

actual sales is more easily measured and

verified, less subjective, and therefore

more fair than previous bases for

assessment.

Back in colonial days, when the assessor went to George Washington's home

in Mt. Vernon, he simply counted the

number of fireplaces. Assessment of

value is much more complicated today.

The history of assessment in Chicago

and other cities indicates that the target

of assessment uniformity is not reached,

it is only approached. This is, in part,

because houses are not sold every year,

and estimates of value are therefore an

approximation, although an increasingly sophisticated approximation. A

statistical measure of the uniformity of

assessment is called the coefficient of

dispersion. The lower the coefficient of

dispersion, the greater the uniformity of

assessments. Cook County Assessor

Tully claims that with the new assessments, he is attaining a 7 per cent coefficient of dispersion on assessment of

single family homes. This would compare very favorably with the 20 per cent

coefficient of dispersion which is considered acceptable.

Owners of older homes, which were

generally underassessed under the

previous depreciation formula, have

done much of the complaining. In

contrast, a resident of a 1960's ranch

house in Evanston whose tax bill has

exceeded $2,000 for the last four years

received a slight decrease this year.

"We've been carrying the load for those

underassessed properties for years," the

Evanston homeowner said. "What are

they complaining about now? They've

had a free ride."

Fragmentation of authority

A property owner may remember last

year's tax bill and have an idea of the

proportion of tax going to the different

local governments. But no government

January 1978/ Illinois Issues/ 5

is responsible for next year's total tax

burden. There is no single official who

has the authority or the information to

say, "Next year your taxes will be so

many dollars."

In most cases, one authority doesn't

know what the next one is doing. The

village and the school district may have

different fiscal calendars. It's doubtful

that the village trustee and the school

board member discuss their proposed

levies, and it is most unlikely that either

of them know when the General Assembly, which has the authority in this case,

increases the tax rate limit for the

Metropolitan Sanitary District. Each

government makes decisions independently and hopes to get by for another

year. It's not surprising that the taxpayer doesn't know what's coming. No

one else does either.

The local official's task is made more

uncertain because the amount of revenue that can potentially be raised is

unknown, particularly in the year the

quadrant is reassessed. While the budget

and the levy are debated, officials know

neither the assessed valuation nor what

equalization factor the Illinois Department of Local Government Affairs will

assign so that Cook County's aggregate

assessed valuation, like that of other

counties in Illinois, will be 33 1/3 per

cent of fair market value as required by

law. Equalized assessed valuation is

unknown until the equalization factor is

assigned, and this takes place months

after

the levies are passed. Therefore,

the levies of those units of government

with tax rate limits are based on

educated guesses.

Often a small percentage of the

eligible electorate served by a local

taxing body votes at referendum elections to determine increases in tax rates.

For example, only 14 per cent of those

eligible voted at a referendum for

Evanston Township High School which

increased the maximum Education

Fund tax rate by 40 per cent for all of the

taxpayers in the district.

Fragmentation of authority is comfortable, in a way, for officeholders.

Local officials can honestly say that they

don't assess the property; the assessor

can honestly say he doesn't levy the

taxes; the local school board can say

that the equalization factor is unpredictable. And fragmentation of authority is

built into our system of local government. But fragmentation is not comfortable

for the taxpayer who doesn't know

what's coming and then can't find

anyone to blame. Of course, tax rates

are increased by direct vote of the

taxpayer/ voter in referenda, or by

elected representatives who vote to

increase tax rates, often in response to

demands for services. Under our theory

of democratic government, the voters

are responsible for increasing taxes. In a

sense taxpayers should say, along with

Pogo, "We have met the enemy and they

are us." But no one says that.

The double wallop

Cook County collects taxes in two

installments. Because the first tax bill is

sent out before tax rates are computed,

it does not reflect new rates or increased

levies. It is simply 50 per cent of the

previous year's tax bill. The total

increase in the 1976 tax bill is added to

the second installment, thus delivering a

double wallop. For example, in Evanston Township there was an average 20

per cent increment in the 1976 tax bill,

but since this was all contained in the

second tax installment, that bill was, on

average, 40 per cent higher than the first.

The letterhead of the tax-protesting

National Taxpayers' Union of Illinois

shows a coiled snake next to the slogan,

"Don't Tread on Me." At a North Shore

tax protest meeting sponsored by the

group, one of the protesters compared

the increasing tax bills to fascist Germany and drew cheers from the crowd

when he said, "This is a Nazi method,

not an American one." He was wrong.

Fragmented local government and

property taxes are as American as the

Electoral College.

There have been many official reactions to the tax protests. Interestingly

enough, proposals for relief did not

come from the local school boards

whose budgets take 60-75 percent of the

suburban Cook County real estate

dollar, nor from the city councils that

take approximately 20-25 per cent, but

from the Cook County assessor, the

Cook County Board president and the

state representatives. The reasons they

responded are probably political as well

as functional. They are professional

politicians, and they know that angry

taxpayers are angry voters. They also

have a broad view of the problem and

more knowledge of the legal and political machinery available for solutions.

Significantly, it is the political process

and the politicians who can channel

information, define the issues, develop

consensus and resolve conflicts. These

are the vital functions, sometimes

forgotten, that politicians perform

society.

Massive property tax relief is not

likely, but some adjustments may be

possible. And confidence in the equity

of the system is necessary. Proposal

under consideration, and some changes

have already taken place.

Short-range proposals attempt to

reduce the impact of sudden tax increases by giving relief to senior citizens,

increasing information about assessments, reducing assessment levels,

reassessing annually, challenging windfall

taxes and limiting dates for referenda.

Relief to senior citizens

The impact of increased taxes is

greatest on persons on fixed incomes

and special laws already exist for

persons over 65, specifically the circuit

breaker and the homestead exemption.

The circuit breaker offers a cash rebate

from the state to low income senior citizen homeowners and renters for

a portion of property taxes. Legislation

passed in 1977 increases the maximum

rebate to $650.

Where the circuit breaker distributes

state funds to low income seniors,

homestead exemption removes $1,500

equalized assessed valuation for each

home owned by senior citizens from the

tax base, thereby redistributing the tax

burden to the other local taxpayers.

Assessor Tully, speaking before a

subcommittee of the House Revenue

Committee, proposed that the General

Assembly act quickly to increase this

exemption to $3,000.

New legislation requires that the

mailed notice of an assessment change

should also contain information about the current and previous year's full

market valuation, percentage of assessed valuation, an explanation

of the relationship between assessment

and the tax bill, equalization and the appeal procedures.

Reduction of assessment

After the angry response to the 1976 bills, Tully again proposed that Class II

single family residences be assessed at 16 per cent, and the

Cook County Board agreed. Reassessment of

the next quadrant, northwest Cook

6/ January 1978/ Illinois Issues

County, will be 16 per cent of fair market value for single family residences, and 1977 assessments on homes in the north quadrant will be reduced to 16 per cent. However, reduction of tax bills will not materialize if tax rates increase as anticipated.

Modifying the impact

Annual rather than quadrennial reassessment of Cook County property would distribute inflationary increases each year rather than once every four years. Real Estate Research Corporation reported that 39 states had annual reassessments in 1971. Assessor Tully appointed a blue ribbon committee to consider assessments and tax relief and asked the committee to consider the practicality and feasibility of annual assessments as well as the manpower and resources necessary for administration. Tully says it might be possible to institute annual assessments by 1980.

There are also proposals to reduce the impact of the second tax installment by increasing the number of installments or redistributing the anticipated increase.

Windfall is a term applied to taxes raised as a result of increased equalized assessed valuation. That is, if a taxing body is limited to a rate of $2.00 per $100, and reassessment results in an increase from $100,000 to $150,000 equalized assessed valuation, the taxing body can levy and collect $3,000 rather than $2,000 without changing the tax rate. The additional $1,000 is a "wind-fall." Many people feel that the purpose of limited tax rates is undone when assessment values change rapidly. A class action suit has been filed to return unexpected revenue to the taxpayers.

State Rep. Woods Bowman*(D., 11 th District) intends to introduce a number of legislative proposals dealing with the whole range of adjustments to the impact of sudden tax increases. He is also proposing an intracounty equalization system to distribute the tax burden more equitably throughout the county each year. State Reps. James McCourt (R., 11th District) and John Porter (R., 1st District) have also announced their intentions to seek

legislative remedies. Limitation of referendum elections to designated election days is part of a new election calendar passed by the General Assembly. Although an amendment to that bill allows for emergency referenda to be held, with the

circuit courts deciding whether a request for a referendum by a local governmental unit qualifies as an emergency.

It will take effect December 1, 1978.

School aid formula

The taxpayers are not the only ones suffering. Many school districts are balancing between increased property tax revenues and decreased state funds. State support of the schools is keyed to the complex resource equalizer formula. But, generally, when equalized assessed valuation rises for a school district, state support is reduced; when school enrollment drops, state support is reduced. Both are happening at the same time. Take the case of Arlington Heights School District #25. They passed a referendum and increased their tax rate $.52. Their equalized assessed valuation also rose significantly. Increased tax rate multiplied by increased equalized assessed valuation means a lot of money. But the increased revenue will pay off a deficit and District #25 will lose about $1.8 million in state funds this year. Costs are going up, state support going down, and another referendum is unthinkable. This problem is not limited to Cook County but affects school districts throughout the State, according to State Supt. Joseph M. Cronin.

In addition to proposals for legislative changes, several groups are focusing on the equity of tax assessments. Confidence in the basic equity of a tax system is necessary. Local studies allege that some assessments are too low and that certain types or classes of property (land, high priced houses, commercial and industrial property) are underassessed, but evaluation of these studies will take time. (Is the sample sufficient? The data accurate? The assumptions valid?) While a complaint form for underassessed property filed at the assessor's office will be investigated, Tully says only 20 such complaints were received in 1976. If allegations of underassessment continue, that number may increase.

Long-range changes

John Castle, director of Illinois Department of Local Government Affairs, gets complaints about property taxes from all over the state. "Ifs not a Cook County problem," says Castle. In addition to administrative reform of the

property tax, castle warns to consider total reform of the tax system. "The people applauding an increase in the Homestead Exemption at the taxpayer protest meeting don't realize who will pay the portion of the taxes from which senior citizens are exempted — the rest of the taxpayers will pay it. What we need is total reform," says Castle. One specific reform Castle would like to see is the separation of property taxes from the state school aid formula.

Shifting some of the tax burden to state, county, or school district income taxes has also been suggested. Cook County Board President Dunne suggested an increase in state income tax might give relief to property taxes. Norman Beatty, executive director of the Civic Federation, suggested a county income tax. School district income taxes have also been proposed. The prospect of hundreds of different local income tax systems makes the administration of property taxes look simple.

Why don't governments spend less, or at least less of the property taxpayers' money? Actually, the seven major governments in Chicago have become less dependent on property tax in the last 10 years, according to Lavern Kron, director of research of the Civic Federation: "In 1966 these seven governments received 41.3 per cent of their revenue from property tax. In 1976 they received 31.2 per cent of their revenue from property tax."

Dunne says, "We reached the saturation point on property taxes five years ago. Cook County has not increased its corporate levy in five years." The county has turned to other sources of revenue such as the liquor tax, but these are not available to school districts, park districts and special purpose governments.

Everyone dislikes the property tax — until the alternatives are considered. But there are still advantages to this tax. It is enforceable and collectible, even when the taxpayers are upset; it yields a substantial amount of money, and it is an institution. "After 100 years of intense criticism from economists, public administrators, and the general public, it remains the single most important tax source of local government revenue," states Diane B. Paul (The Politics of the Property Tax, D.C. Heath & Co., 1975).

Continued on page 29

January 19781 Illinois Issues / 7

Property tax revolt in Cook County

Continued from page 7.

Yet, real estate does not represent wealth in the same way it did many years ago. Appreciation in the value of real estate does not mean an increase in current income especially for those whose incomes are fixed. The possibility of people selling their homes because they can't afford to pay taxes hovers in the background of any discussion of rapidly rising property taxes. "To tax and to please, no more than to love and to be wise, is not given to men," said Edmund Burke more than 150 years ago.

But men, and women, are still trying to tax and to please. Assessor Tully's committee is to report by January 15, 1978. Cook County Board President Dunne also appointed a committee to study the equity of assessment practices, and Gov. James R. Thompson has asked the Department of Local Government Affairs to hold hearings on property taxes.

Tom Tully's announcement that he will not be a candidate for reelection was the first surprise in the 1978 race for Cook County Assessor. The second surprise, perhaps, was President of the Senate, Thomas C. Hynes' announcement to run for that office. (See "Politics" on page 33 of this issue.) That race is worth watching, for while political campaigns do not usually lend themselves to discussion of the "issues," they can register shifting voter attitudes.

Meanwhile, like Old Man River, the administration of the property tax system just keeps rolling along. Property in the northwest quadrant of Cook County was reassessed at the end of 1977, and the southwest quadrant will be reassessed in 1978. School districts, park districts, cities and villages and other taxing bodies are deciding their 1978 tax levies now. And Cook County, the second largest county in the U.S., will send out property tax bills to the 1.3 million taxpayers again this spring.

January 1978/ Illinois Issues/ 29

Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the

Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator

|

|