By CHARLES N. WHEELER III Legislative redistricting will determine the political shape of Illinois in the 1980's

Reapportionment begins now!

THE "typical voter" for an opinion on legislative reapportionment, and chances are you'll get a blank stare in return. Those who have heard of the subject likely consider it to be the proper domain only of demographers and cartographers, something over which political leaders smack their lips and editorial writers wring their hands. But it's more than just "slicing the salami," as one old-time politician put it. All those squiggly lines running hither and yon on the state map translate into considerable impact on Mr. Voter's everyday life. Past reapportionments in Illinois, for example, usually have determined whether Mr. Voter will be represented by Democrats or by Republicans in the Illinois General Assembly. A basic rule of thumb for the mapmakers has been to fashion the vast majority of the districts so they would be "safe" for one major party or the other, leaving only a handful of "swing" districts to move with the shifting political winds. "That way, in any given election, control of the legislature can change with the will of the people," explained one expert in the field. Balanced map The current map was drawn for balance; its architects proclaimed that 28 districts would elect Democrats, 28 would elect Republicans, and the remaining three would be uncertain, in most years. Another cardinal rule has been to attempt to protect incumbents by designing districts to meet their needs. One basic consideration, of course, is to avoid putting more incumbents into a district than there are seats to be filled. The effort sometimes results in strange configurations. In 1965, the new Senate map worked out by party leaders and the courts included one district on Chicago's Southwest Side from which hung a scrawny appendix two blocks wide and 10 blocks long, called the Whitey Cronin corridor. The strip was designed to link the new district to the home of Sen. A. L. "Whitey" Cronin, a popular Democrat whose old district was carved away in the reapportionment. The well-intentioned efforts to provide Cronin a district from which to run went for naught, however. A Republican living at a more central location in the district upset the 12-year Senate veteran by 1,330 votes. These common reapportionment guidelines — making politically safe districts and protecting incumbents — have come under fire from reform groups who argue they dilute the value of citizens' participation in politics, make legislators less responsive to their constituents and permit parties to field weak candidates. To remedy these perceived evils, one such group, Common Cause, has proposed establishment of an independent, nonpartisan commission to draw district lines to remove the inherent conflict of interest present when legislators draw the lines. Others have turned to the courts. In one case, after a three-judge federal panel agreed that Illinois congressional districts were malapportioned, the plaintiff Sherman Skolnick, a self-styled legal researcher from Chicago, declared his suit was "a way to get the political hacks out of office without firing a shot. We're not going to stand for any hanky-panky wherein they can have safe districts that look like cigars, or a snake, or fishhooks," he asserted. Despite the reformers' efforts, reapportionment in Illinois is first of all a legislative duty, according to the 1970 Constitution. Only if the legislature fails does the task pass on to another body, and that is a redistricting commission named by legislative leaders. But, the effects of reapportionment are not felt just at election day. They permeate many of the crucial issues facing the General Assembly — any topic on which the major parties or the competing areas of the state strongly identify with opposing views. November election The subject of reapportionment is particularly relevant now, with the November general election close at hand. The two-thirds of the Senate to be elected this year will form the nucleus of the upper chamber for the state's next redistricting three years hence following the 1980 census. The process in 1981 may present the Republican party a golden opportunity to map itself into a position of legislative dominance for the next decade, thanks to a combination of political fortune and changing demographics

CHARLES N. WHEELER III August 1978/Illinois Issues/7 which appear to favor the GOP. Republican strategists — and most impartial pundits — expect Republican Gov. James R. Thompson to defeat handily his Democratic challenger, Illinois Comptroller Michael J. Bakalis. The GOP scenario calls for dozens of Republican legislative candidates to sweep to victory on Thompson's coat-tails, perhaps enough to overcome the Democrats' 34-to-25 Senate advantage and 94-to-83 House margin. The timetable then calls for Republicans either to maintain control or to achieve it in 1980, so that the General Assembly drawing the new map, and the governor signing the measure, will be Republican. Whetting GOP appetites for the mapmaking process are projections of massive population shifts away from Chicago and into the suburban areas. Under the U.S. Supreme Court's "one man, one vote" rulings, legislative seats should follow the fleeing city dwellers to Republican suburbia. Suburban gains Thus the key issue in the 1981 remap fight is likely to be: Will the balance of power shift from Chicago to the suburbs if the 1980 census reveals the huge city emigration everyone predicts? It's not a new issue. Reapportionment in Illinois has not been an easy task at any time in this century, and the biggest stumbling block has always been what to do with Chicago and Cook County. The 1870 Constitution mandated the legislature to apportion the state by population after every decennial federal census. Districts were to be "formed of contiguous and compact territory, bounded by county lines, and [should] contain as nearly as practicable an equal number of inhabitants." In the first reapportionment after adoption of that charter. Cook County, with 13.8 per cent of the state's population, was alloted 7 of the 51 districts. For the rest of the 19th century, the legislature faithfully discharged its duty, each decade increasing Cook County's share of the districts as that area's population burgeoned to 1.8 million by the 1900 census: • Act of 1882, Cook County with 19.7 per cent of the state's population, 10 districts. • Act of 1893, Cook County with 31.2 percent of population, 15 districts. • Act of 1901, Cook County with 38.1 percent of population, 19 districts. But after the 1910 census, which showed some 43 per cent of the state's citizens living in Cook County, the legislature failed to allot to the county the extra three districts to which it was entitled.

Historians give a cogent reason why there was not to be another redistricting for more than half a century: Downstate rural-oriented legislators realized that faithful adherence to the Constitution's reapportionment mandate inevitably would transfer control of the state's legislative branch to the urban interests of Cook County. By the 1930 census, Downstate fears were a reality; Cook County had 52 per cent of the state's residents, though they were represented in the legislature by only 37 per cent of the lawmakers from the 19 districts of 1901. Stratton's determination The imbalance persisted until 1953, when the newly inaugurated governor, Republican William G. Stratton, was determined that the Assembly should be apportioned on a more equitable basis. Stratton was motivated by more than a sense of justice and fair play; he realized much of Cook County's growth was in the Republican controlled suburban areas. The 1950 census showed Cook County with some 52 per cent of the population, so its residents were entitled mathematically to a majority in the legislature. But there was strong opposition to giving Cook County its fair share. "I know members of the House of Representatives who, if you reinstituted the rack, would not vote for reapportionment that would permit the County of Cook to dominate the Legislature, either at the Senate or at the House level," declared House Speaker Warren Wood, a Plainfield Republican, in 1953. Despite the opposition of Wood and of House Democratic Leader Paul Powell of Vienna, a constitutional amendment to reapportion the legislature threaded through both Senate and House and was approved by voters at the 1954 election. In an effort to allay Downstate fears, the amendment departed from the 83-year-old idea that legislative districts in both chambers were to bear some relationship to population. Instead, it adopted the same kind of area-population amalgam that exists at the federal level. There were to be 58 Senate districts, an increase of seven, arranged as follows: 34 Downstate, 18 in Chicago and 6 in suburban Cook County. The amendment clearly spelled out that for the formation of Senate districts, "area shall be the prime consideration." Its terms guaranteed that Downstate, though having less than half the state's population, would control the Senate by a 10-district edge; the margin was to be eternal, for the amendment contemplated no further change in Senate boundaries once the 1955 lines were drawn. Politically, the division seemed to assure Republicans the same perpetual control of the Senate, which they had enjoyed for all but 12 of the previous 60 years. For devising House districts, of which there were to be 59, population was the key determinant and the legislature was to reapportion after every federal census. Districts were to be apportioned among the city of Chicago, the Cook County suburbs and the other 101 counties according to each political subdivision's proportionate share of the state population, with individual districts then drawn within the subdivision boundaries. For the 1955 reapportionment, Chicago was allotted 23 districts, the Cook County suburbs 7 and Downstate the remaining 29. To insure the legislature would not ignore the constitutional order to reapportion — as it had the old mandate — the new procedure called for a commission to do the job should lawmakers fail and for an at-large election of all House members if the panel did not produce a map. In 1955, such draconian penalties were not needed; the General Assembly drew new districts according to the amendment's guidelines and Stratton signed the bill 8/August 1978/Illinois Issues

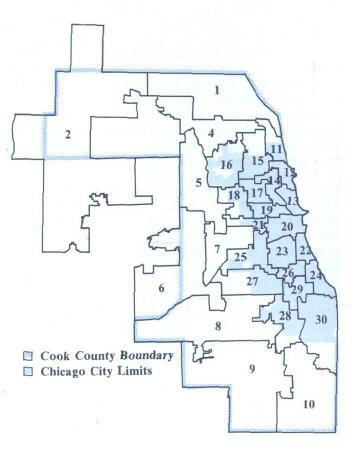

into law. Not surprisingly, the districts were designed as much as possible to protect incumbents and to strengthen each party in its dominant areas. Kernels veto When it came time to redistrict the House eight years later, the Republicans controlled both chambers, but a Democrat, Otto Kerner, was governor. The GOP sent the governor a House reapportionment bill, but Kerner vetoed it because of population inequities (the largest district had more than twice as many residents as the smallest). A key point of contention was how many districts Chicago should have. Population shifts from the city to the suburbs registered by the 1960 census indicated that two of Chicago's 23 districts should go to suburban Cook County. Democrats instead wanted to overlap districts on the city's edges just far enough into suburban territory to pick up the additional population needed to justify keeping all 23. Republicans contended such an arrangement would violate the state Constitution's "Chinese Wall" separation of Chicago, suburban Cook County and Downstate. When the redistricting commission also failed to resolve the dispute, all 177 House members were elected at large in the 1964 election. When the 74th General Assembly convened the following January, a new element had been added to the reapportionment snarl — the Illinois Senate. In a landmark 1964 ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court held that both chambers of a state legislature had to conform to the one-man, one-vote principle. "Legislators represent people, not trees or acres," wrote Chief Justice Earl Warren in Reynolds v. Sims. "Legislators are elected by voters, not farms or cities or economic interests .... We necessarily hold that the Equal Protection clause required both houses of state legislature to be apportioned on a population basis." Judicial remap Once again, the legislature was not up to the task, as the Republican Senate and the Democratic House were unable to decide what to do with Chicago. So the task of redistricting the Senate fell to the Illinois Supreme Court, with the federal courts looking on, while the House was to be remapped by another redistricting commission. Federal and state judges and party leaders reached a compromise on the Senate by late summer, and the Illinois Supreme Court adopted a map calling for 21 Chicago districts, 9 suburban Cook County districts and 28 Downstate districts. The greatest divergence of district population from the state median was 7 per cent. None of the districts breached the "Chinese Wall" separating the state's three constitutionally ordained divisions — Chicago, suburban Cook County and Downstate. The House commission reached agreement later in the year, thus avoiding another at-large election. The panel accepted the same district lines for the 21 Chicago and 9 suburban Cook County districts as were contained in the Senate map, then drew completely different boundaries for the 29 Downstate districts. 1970 Constitution While the 1970 census was being taken, the Sixth Illinois Constitutional Convention was meeting to fashion a new basic charter for the state. Both events strongly influenced the current apportionment, for the convention laid to rest the notion that districts could not overlap Chicago and the suburbs, or Cook County and adjacent counties. The new Constitution which voters approved late in 1970 says only: "Legislative Districts shall be compact, contiguous and substantially equal in population." Removing the constitutional underpinning from the "Chinese Wall" proved immensely helpful in resolving reapportionment in 1971, when once again the major stumbling block was Chicago's representation. The 1970 census documented another decline in the city's population so that Chicago was entitled to 17 and a fraction districts, instead of the 21 it had, while the Cook County suburbs deserved 11 and a fraction, instead of 9. Chicago legislators were unwilling to lose those seats, pushing instead for overlapping districts that would bring enough suburban voters into city-based districts to meet population standards, but not so many that Democratic control would be threatened. Late in the session, such a map passed the House after leaders of both parties had hammered out a compromise. House Speaker W. Robert Blair, a Park Forest Republican, acceded to Democratic wishes for Chicago. In return, he was given virtual carte blanche to draw Downstate districts as he saw fit to perpetuate Republican control of the legislature. But Republicans in the Senate refused to accept the House proposal, which they labeled a sellout of the suburbs, and the session ended without a map. But the handwriting was on the wall. Under the 1970 Constitution when the legislature fails to reapportion, the task falls upon an eight-member commission whose members are appointed by legislative leaders. Senate President Cecil A. Partee, a Chicago Democrat, House Democratic Leader Clyde L. Choate of Anna, and Blair all named themselves and a top aide to the commission. Senate Republican Leader W, Russell Arrington of Evanston chose former Gov. Stratton and Sen. Terrel E. Clarke, an assistant GOP leader from Western Springs, as his appointees. When the commission, by a 6-to-2 vote, approved a reapportionment plan in late summer, no one was surprised that it proved almost identical to the one Senate Republicans rejected some seven weeks earlier. Both Stratton and Clarke voted against the measure, bitterly denouncing it as "a travesty on the constitution" that made some 400,000 suburbanites "subordinated to the interests and dictates of the city's dominant political organization." Current districts The plan, which set the district lines currently used, places 11 districts entirely within Chicago. Nine others around the city's perimeter overlap into the suburbs just far enough to reach the needed population level, but not so far that Democratic domination would be jeopardized. There are eight districts wholly in suburban Cook County and two others that sprawl into neighboring counties but remain firmly under Cook County control. The remaining 29 are scattered Downstate. The commission's handiwork withstood a series of court challenges, despite the suburbanites' complaints. The Illinois Supreme Court did note, however, that the panel itself was established unconstitutionally because the leaders named themselves to it. Though Blair touted the map as one August 1978/Illinois Issues/9 that assured GOP control of the legislature in normal years, the Democrats won majorities two years later in both houses of the Illinois General Assembly for the first time since 1936. Ironically, one of the "safe" Republican districts that elected two Democrats in the Watergate-tainted election of 1974 was Blair's own Will County base; the speaker, saddled with his role as chief architect of the Regional Transportation Authority, was the casualty. Will history repeat itself the next time the legislature takes up redistricting in 1981 following the 1980 census? Will disagreement over how Chicago and Cook County should be handled force reapportionment to a commission again? To hazard any guesses as to what might happen three years from now, the basic starting point is the state's population and how it has changed in the decade of the 1970's; the soothsayer must project what the state's population will be in 1980 because these census figures will be what the mapmakers will use. Fortunately, the state itself publishes detailed, county-by-county estimates of future population change. Since 1973, the Illinois Bureau of the Budget (BOB) has released data representing the most probable projections of future population changes based on current information. The projections are used as guidelines by all state agencies, boards and commissions in preparing required plans, programs and budget documents. In the most recent revision, published last September, state population was projected to be 11,349,084 in 1980, an increase of more than 236,000 from the 1970 census count. Based on this figure for state population, mapmakers would have to place 192,357 persons in each of the state's 59 legislative districts to be consistent with the U.S. Supreme Court's one-man, one-vote principle. Chicago's loss The BOB 1980 projection for Cook County is 5,261,031, a decrease of some 233,000 from the 1970 census. Based on the projected figure, the county would be entitled to 27 and a fraction legislative districts. Although the budget bureau planners don't include a specific estimate for Chicago, they and population experts associated with other planning groups agree that in the 1980 census the city's population will probably be pegged at a shade less than three million, perhaps around 2,950,000. Using that figure, which is a loss of more than 400,000 from the 1970 count, Chicago would be entitled to only a fraction more than 15 legislative districts — a loss of five districts.

Currently, the city's Democratic organization dominates 20 districts even though by the 1970 figures Chicago is entitled to only 17 plus. But through the device of overlapping 9 districts on the city's borders into suburban territory, the city enjoys the political edge in a total of 20 districts. Suburban Cook County's projected population of 2,311,031 would entitle it to a fraction less than 12 districts, just about what the 1970 census disclosed. But the suburban area currently controls only ten districts (and two of these extend into neighboring counties) because the city put fractions of suburban population into the nine overlapping districts. If Chicago stands to lose five districts, and suburban Cook County should gain two, where do the other three belong? According to the BOB projections, the fastest growing area in the state is the five-county region surrounding Cook County. Those three Chicago districts should be shifted to this collar county area, whose population is projected to increase by some 347,000 to more than 1.8 million. The projected increases include: Lake, 54,404; McHenry 33,938; Kane, 36,481; DuPage, 121,809, and Will, 100,332. In the other 96 Downstate counties, the total population is projected to grow only slightly, less than 3 per cent, compared to the almost 15 per cent growth in the Chicago suburban areas. The BOB projections for the Downstate counties generally show loss of population along the state's western and eastern borders, and solid growth in the central portions of the state. Thirty-five counties are expected to lose population; the other 61 are projected to grow. Because of the usually large areas associated with Downstate legislative districts and the relatively small overall population change, Downstate districts probably could be made to conform with the new population requirements with only minor adjustments of boundaries. Districts in Western Illinois and Eastern Illinois would have to increase their size to take in more population to make up for losses, while those in Central Illinois could be expected to shrink in size. In Northern and Southern Illinois, losses in some counties are likely to be offset by gains in others, so the overall impact on the size of legislative districts could be slight. Of course, the mapmakers could abandon completely the existing boundaries and fashion a new map from scratch. But even should they do so, the 96 counties' 4.3 million population would entitle them to only 22 and a fraction districts, just about what they have now. Thus, the single most striking problem for the 1981 reapportionment is likely to be the same old dilemma — what to do with Chicago. Overlapping games Could the city somehow save its threatened districts, perhaps by utilizing the same overlap technique that was used in 1971? To meet the court guideline, 20 Chicago districts would require a total population of 3,847,140, based on the projections. That's almost 900,000 more residents than Chicago is likely to have. Those 900,000 people would have to be taken from the suburbs. Adding the extra population to the nine city districts now extending into the suburbs would require placing almost 100,000 suburban voters into each overlapping district, giving the suburbs some 52 per cent of the total population — a situation in which the Chicago Democrats could not be sure of control, especially along the city's North and Northwest fringes. Even though the existing nine overlapping districts were drawn to give Chicago at least a 2-to-1 edge in population, those suburban voters have given organization Democrats fits in several districts. While not enough to shift the districts to Republican control, 10/August 1978/Illinois Issues they have been able to replace regular Democrats with mavericks on occasion. "I think when Chicago Democrats extended the districts into the suburbs, they thought they were maintaining the status quo," said one Democratic legislative veteran. "But they made it possible for independent Democrats to be elected from those areas." Chicago Democrats probably would not be assured of controlling legislative races in the 1980's if only the current nine overlapping districts were given more suburban population. If all 20 city districts, however, could somehow receive an equal influx of suburban residents, city dwellers would outnumber the suburbanites in each by better than 3-to-l margins. But it is doubtful whether such creative cartography would survive the constitutional "compact and contiguous" test since such districts of necessity would have to resemble classic bowling alley gerry manders. "Chicago will try to reach into the suburban areas for additional population," predicted House Minority Leader George H. Ryan, a Kankakee Republican. "They've nowhere else to go. But I couldn't be for it. That's good Republican ground they want to go for." What Republican mapmakers should look for, according to Ryan, who well might be handling the task for his party in the House, is a map that would elect GOP

August 1978/Illinois Issues/11 legislative candidates. Should Republicans control both House and Senate in 1981 and choose to play the Chicago Democrats' overlap game, suburban Cook County could easily absorb two Chicago districts by nibbling away at the city's edges. The projected population for the Cook County suburbs is 2,311,031, which would be just 318,967 short of the population required to support 14 districts within the Cook County Republican suburbs. If Republicans overlapped boundaries for nine of these projected 14 districts to include about 43,000 Chicago residents in each of the nine districts, the result would be suburban control of 14 districts. Chicago would be stripped of two more districts, thus reducing Chicago Democratic districts to 13. The current nine districts overlapping city and suburban county territory might serve the purpose, were they shifted outward from the Loop to envelop more suburban area. How likely is it that such a catastrophe would befall the city Democrats? One Democratic leader discounts it happening, explaining that each party is more likely to develop its own priorities for reapportionment, rather than trying to accommodate the other party on less important remap points. While the Democrats might opt to preserve Chicago strength, the Republicans might be more interested in fortifying their Downstate positions, as happened in 1971. Additionally, the Democrat noted, reapportionment doesn't occur in a vacuum — there will be legislation pending in the General Assembly over which bargains can be struck to save Chicago districts. "But the potentiality is there for problems," he conceded. Chicago 'catastrophe' Assuming the worst, from a Chicago point of view, what would be the impact if the city lost seven districts to the Republican suburbs? The most immediate result would be a shift in the partisan balance of the legislature. The Democratic party would be weakened severely, particularly in the Senate. During the decade of the 1970's, only once have Republicans been able to win a Senate race in Chicago, and that was in a district which included a large number of suburban voters and weaker-than-usual city wards. So it seems certain those seats moving to the suburbs would be Democratic seats and there would be virtually no hope Democrats could be elected from most of those newly created suburban Senate districts. On only three occasions in this decade have Democrats won Senate seats from the suburbs, and two of those were in 1974 when the stench of Watergate severely reduced Republican turnout. The Senate currently has 34 Democrats and 25 Republicans. Shift seven seats to the GOP side of the ledger, consider that Democrats are conceding in private that they don't expect to retain several of the seats they now have outside of Chicago, and it's easy to see why such a reapportionment would cement Republicans into Senate leadership at least until 1991. The effect of these potentially drastic changes in Chicago area districts is more difficult to foresee for Democrats in the House. The vagaries of cumulative voting sometimes permit a minority party to elect its two candidates to the House in a given district when the top vote-getter for the majority party greatly outdistances his running mate. No Chicago district has elected two Republicans to the House in the 1970's, but in five instances. Democrats have swept all three seats. Republicans have been almost as consistent in the suburbs, though Democrats have captured two of the three seats on occasion in certain suburban districts, particularly the South Suburban 9th and the West Suburban 5th. It's likely, however, that the GOP mapmakers who might strip Chicago of seven districts would also take pains to see that something is done about those existing suburban districts in which Democrats have shown success. Redrawing south suburban lines, for example, to dilute Democratic Cook County strength with solidly Republican precincts from eastern Will County might put an end to Democratic victories there. Similarly, the 5th District could be shifted northward to encompass stronger Republican territory. Democrats in Chicago, of course, could try to offset losses by electing three House members from as many city districts as they could. So far, Democrats have consistently taken three spots in only one district, the South Side 26th. There the third Democrat runs as an "independent," then formally aligns himself with the party after the new legislature has been sworn in. But political observers suspect Democrats could post clean sweeps in many of the predominantly black districts, from which GOP candidates now are elected to the House with only a handful of votes, as well as in some white areas where the regular organization is especially powerful. In the 1976 general election, for example, the total Democratic vote for representatives more than tripled the total Republican vote in seven districts aside from the 26th, where three Democrats were elected. This would indicate that three Democrats could have been elected in each of those seven districts, if each candidate received exactly one-third of the Democratic vote, and all the Republican vote went to one GOP hopeful. Because Democrats only nominated two in each of those districts. Republicans were able to claim the third spot almost by default. If Chicago Democrats were cut down to 13 districts, perhaps Democrats could elect all three representatives in half a dozen or more city districts. But the attempt might trigger GOP retaliation in those areas of the state where Republican strength is overwhelming. Legislative control Since the House now has 94 Democrats and 83 Republicans, the potential for a shift in control is obvious. If Chicago loses seven districts. Republicans could gain some crucial House seats, although not with the same ironclad guarantee of success they might enjoy in the Senate. In any case, the significance of this potential shift cannot be underestimated, given the importance of controlling a legislative chamber even by a single vote. Starting with the election of the Senate president or the House speaker, that vote can have far-reaching impact, especially since the majority party controls the committee system, including the all-important committee that assigns all bills to hearing committees. The majority party traditionally stacks the committees in its favor, so that the minority is unable to move legislation without the majority's support. Committee control is tantamount to setting the agenda for the session; bills the majority does not favor are squelched in committee, while the majority's program is reported favorably to the floor. 12/August 1978/Illinois Issues Control of the chamber also carries with it control of the gavel, and thus almost absolute control over floor action. A skilled person in the chair can adroitly maneuver legislation so that favored bills are called for action at a propitious time, while unpopular bills are called at inopportune times — like late in the afternoon on a day when the legislature is scheduled to adjourn for a weekend. By choosing to recognize one speaker and not another, by imposing strictly the debate time limits on one speaker and not another, even by cutting off a member's microphone, the person in the chair can manage the debate. Finer points of controlling debate include prolonging it to allow a sponsor to seek out the extra votes he needs to pass a bill or curtailing debate before a sponsor can find those additional votes. Procedural and parliamentary rulings from the chair help determine the outcome of legislation. For example, the state would have a far different get-tough-on-crime package had House Speaker William A. Redmond, a Bensenville Democrat, not ruled in June 1977 that the Senate amendment embodying Gov. Thompson's "Class X" proposal was not germane to the House bill chosen to be its vehicle. But the significance of seven fewer districts in Chicago goes beyond merely choosing legislative leaders. In the Senate, the shift would probably mean seven additional suburban Republicans and seven fewer Chicago Democrats. In the House, based on the current breakdown, 14 Chicago Democrats and 7 Chicago Republicans would be replaced by 14 suburban Republicans and 7 suburban Democrats. The impact, however, is greater than the loss of 7 Democratic seats in the House; it means exchanging 21 usually reliable votes for 21 unpredictable, potentially hostile votes on issues important to Chicago. So the forthcoming reapportionment could greatly influence the scores of questions upon which the legislature frequently is split along partisan or sectional lines.

In the House, for example, Chicago Republicans traditionally support their Democratic brethren on issues vital to the city. So far, no viable suburban bloc has emerged in the legislature. Under the scenario being considered, however, Suburbia would control 24 districts — 14 in Cook County and 10 in the collar counties — and perhaps would have the numbers to forge an effective coalition on issues important to suburban residents. Shift seven districts from Chicago to the collar counties and suburban Cook, then consider: • How long would labor's current advantage over business continue in the General Assembly? • How successful would Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) backers be in repulsing the recurring assaults, usually led by suburban legislators, on the transit agency's financing and powers? • How likely would the Chicago schools be to receive the same disproportionate share of state school aid they enjoyed last year? • How much would chances for passage improve for so-called "good government" or "reform" legislation which Chicago Democrats usually oppose? • How unified would the Democratic party remain with Chicago's influence diluted? Business and labor A study made by the Illinois State Chamber of Commerce, a leading business spokesman on legislative matters, showed that the Senate and the House voted on the side of the Illinois AFL-CIO (and thus labor) at least 60 per cent of the time. In contrast, the business position in the 1977 session had minority support of only 23 senators and 86 representatives on as many issues. In 1975, the legislature passed sweeping revisions of the state's workmen's compensation and unemployment insurance programs, giving labor a victory beyond its wildest dreams. For the last three years, the business community has been fighting in Springfield to roll back some of the benefits labor won, but with little success. The 1975 changes would not have been possible without top-heavy Democratic majorities in the House and the Senate. Rolling them back won't be possible, in all likelihood, while the Democrats are in control. This spring, for example, all the business-backed revisionary bills died in committee, gunned down by the Democrats' guaranteed vote margin. Had Republicans been in control, one GOP leader claims, not only would the measures have made it to the floor, but they probably would have gone to the governor for his signature. Nor would business' gain be limited to Republican votes were the seven districts shifted from Chicago to the suburbs. According to the state chamber study of voting records, suburban Republicans voted with business more often than their party colleagues from Chicago. Most Chicago Republicans voted the "right" way more often than not according to the AFL-CIO standards. A fifth of the Democratic House members from the suburbs voted with the business position at least 40 per cent of the time. But only two of Chicago's 41 Democratic representatives and two of its 20 senators scored that well by the chamber's tally. So suburban representatives as a group, regardless of party, tend to be more amenable to business goals and more willing to buck the union position than their Chicago colleagues. The RTA Legislative leaders agreed that the RTA could be in trouble if the balance of power shifts to the suburbs. Suburban legislators from both parties are almost unanimous in their belief that the four-year-old transit agency should be revamped to provide better treatment for their constituents. While it would probably take more than reapportionment to set the stage for dismantling the RTA, as some Suburbanites wish, additional political clout for the suburbs could be translated into such immediate, nitty-gritty items as a differential gasoline tax among RTA service regions and a greater suburban say in day-today operations. During this legislative session, of course, no significant RTA measure has August 1978/Illinois Issues/13 reached Thompson's desk, thanks in part to Chicago Democrats' stranglehold on the transportation committees. But, would a future legislature, in which Suburbanites and Downstaters far outnumber Chicagoans, strike some bargain under which a portion of the motor vehicle-derived revenues now going to the RTA would be tunneled instead into Downstate road repairs? Efforts to forge such a coalition have occurred, but the numbers weren't there. With 7 more suburban senators and 21 more suburban representatives, they might be. School aid The school aid formula is a complex mechanism by which the state parcels out almost $2 billion to more than 1,000 local school districts. Legislators have tinkered with its provisions every session since its adoption in 1973, and the goal has always been the same: get a larger piece of the pie for the school children (translation: teachers' salaries) back home. Chicago has always done quite well, thanks in part to a special weighting factor for poor children that lets city school administrators count each poor kid as a kid and three-quarters, as well as other factors. During the last school year, for example, Chicago received about 41 per cent of the new state dollars pumped into the distributive fund, although the Chicago schools enrolled only about 22 per cent of the state's pupils. Suburban legislators have complained they are shortchanged by the formula. A legislature with strengthened suburban representation and a weakened Chicago representation might decide to slice the pie in a fashion more appetizing for suburbia. Government reform Swapping Democrats for Republicans and city dwellers for suburbanites would have a bearing on such politicized issues as election law, ethics and judicial selection. Republican efforts to extend polling hours until 7 p.m., the better to accommodate returning commuters in heavily GOP suburban areas, have consistently been blocked by Chicago Democrats. So has the open primary notion, in which voters would not have to disclose a party preference to cast a primary ballot. Last spring, Democratic leaders refused to permit any election law reform measure to reach the House floor, effectively forestalling GOP efforts to adopt both extended polling hours and the open primary. Chicago Democrats also have opposed efforts to prohibit double-dipping, the practice of one person holding two public jobs, as a substantial percentage of the Chicago delegation does. Republicans and suburban Democrats, including those lawyers whose double-dipping as attorneys for local governments and school districts would not be barred, generally want to outlaw the practice. Last spring when Gov. Thompson offered in the House a warmed-over version of the ethics package Senate Republicans had helped kill in 1977, Democrats on the House Rules Committee wouldn't even let it be considered. Despite their feelings about the package's merits, Republicans presumably would have at least permitted committee consideration of the governor's plan. The proposed constitutional amendment to have judges appointed by the governor rather than elected by the people fell short in the House last spring, despite a well-orchestrated publicity campaign and a barrage of editorial endorsements. Only a handful of Republicans opposed the suggested change, which was sponsored by a Chicago Republican and a DuPage County Republican. Fewer Chicago Democrats voted for it. The Democratic party Reapportionment would have an influence on party structure, under the dramatic shifts projected here. Electing 7 more suburban Democrats and 14 fewer city ones in the House not only represents a net loss of 7 votes for the Democrats. In all likelihood, it also means a loss of anywhere from 10 to 14 disciplined organization votes upon which the Chicago leader can depend. Suburban Democrats tend to be more their own people, less willing to support a party position for strategic reasons or to participate in the legislative logrolling often needed to form the fleeting coalitions essential to pass any controversial measure. Many suburbanites also make no secret of their dislike for the Chicago organization. Such high principles, lamented one suburban Democat, sometimes carry with them a high price: less scrupulous Downstaters break bread with the Chicagoans and the suburbs are left with only the crumbs. And some believe that increasing suburban representation in the Democratic conferences might exacerbate party fragmentation. But even in the worst case, the Chicago Democratic bloc probably will continue to represent the largest group of easily manageable votes in the legislature. How successful Chicago would be in such a case would depend to a large extent on its leaders' ability to put together the votes needed from elsewhere to achieve its goals. The shift would make the task more difficult for the Chicago Democratic leaders, but not impossible. "Population shifts are going to present a problem for our leadership," acknowledged House Majority Leader Michael J. Madigan (D., Chicago). "But the inherent Democratic vote in Chicago and Cook County will always provide a strong base for the Cook County leader in the legislature." Of course, a clever mapmaker could make life miserable for the city organization itself by skillful tinkering with the boundaries of city districts. The Lakeshore independent redoubts could be extended westward into the Spanish-speaking areas of the Near North and Near South sides, instead of remaining stacked up along the lakefront. Such a shift would raise the possibility that one independent and one Latino, and perhaps no regular, might be elected from these districts. Lines could be drawn to maximize representation for the city's black population. Or a particularly mischievous cartographer could put the fabled 11th Ward, bailiwick of the late Mayor Richard J. Daley, into a legislative district dominated by the black wards east and south of it. If Republicans do control the General Assembly and the governor's office during the 1981 reapportionment, the possibilities are endless. Old power bases to be wiped out, new ones to be created; some issues to be promoted, others to be doomed. The course of state politics to be determined for a decade, perhaps longer. And reapportionment is the key. In the words of one politician who's more than dabbled in the art of creative cartography: "You tell me the results you want, and I'll draw you the map to do it." 14/August 1978/Illinois Issues

|

||||||||||||||||||||