By CATHERINE G. CAHAN

Yes, Virginia, there is a Mass transit in Champaign-Urbana

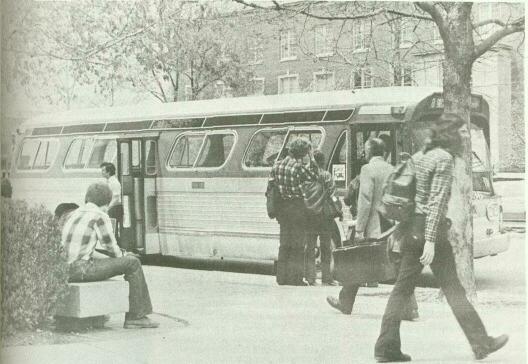

RIDERSHIP — that index of success in the transportation field — nearly doubled on Champaign-Urbana Mass Transit District (MTD) buses last year. The 42.5 per cent increase was the largest percentage growth in ridership recorded for any public transportation system in the United States or Canada from 1976 to 1977, according to the American Public Transit Association. The increase in number of riders has been due mainly to an expansion the MTD undertook in August 1977, adding routes to the system and doubling the number of buses to the present 40, says MTD director William Volk. With the new 10-route network, the MTD had carried 2.1 million passengers by the end of 1977, three times the 708,000 bused in 1974, which was Volk's first year as director. In those four years, and especially since the expansion, Volk says he has learned the truth of an informal law that circulates among those who run mass transportation systems. It is called the chicken-and-egg law, or sometimes the merry-go-round law. It means roughly: if you can get riders on your buses, then you can command federal, state and local tax dollars, which will allow you to improve and expand your service so you can get riders.... State and federal transportation departments were not yet funding public transportation in early 1974, so Volk

CATHERINE G. CAHAN

October 1978/ Illinois Issues/21 saw only one way to hop on the merry-go-round: get more riders on MTD buses. He says he knew that would be more difficult than it sounded. Like bus companies throughout the country, the line in Champaign-Urbana was privately owned until the early 1970's. Ridership, on the decline since the public transportation boom of World War II years, had sunk to levels that no longer financed the services. One after another, nearly bankrupt companies had been curtailing service and hiking fares since the 1950's. When Danville's system went out of business in the early 1970's, other downstate communities got a glimpse of what was ahead. Champaign-Urbana, like systems in Decatur and Bloomington, was taken over by local government. Local taxes and fares had to cover expenses.

In spite of the community's willingness to tax itself to maintain bus service, Champaign-Urbana's MTD was not much better off than its privately owned predecessor. Inconsistent management and constant money woes allowed no improvements, and some routes ran at as much as 90-minute intervals. More people rode, but the number hovered around 558,000. "I don't know if I would do it again," Volk says with a smile. "I was only two years out of college and my enthusiasm overshadowed my good judgment." Even though a check of his budget showed "the money wouldn't last through the year," Volk says his most serious problem was that residents viewed the MTD as poorly run, undependable and inconvenient. He could not afford new buses or routes, so the 25-year-old manager decided that dependability and service would be the MTD's way to woo passengers and try to qualify for federal and state grants he thought would be coming. His drivers were urged to be courteous and were instructed in the importance of keeping buses running on time. A telephone company check of MTD phone lines showed 300 busy signals in a two-week period, so lines were added. The MTD began answering all complaints by letter. Competing with cars "Just the existence of buses won't sustain riders," Volk says. "When you are competing with the automobile, the ultimate freedom machine, you have to respond to people's needs, not have them fit transit's schedules." By the summer of 1974, the MTD had begun a marketing program, planned by Thomas Costello, now assistant managing director of the district. "The first newspaper ad said, 'We have made some mistakes in the past, but we will improve service, we will get better,'" Volk says. "It wasn't anything fancy. A lot of systems make the mistake of marketing things they cannot produce." Along with sprucing up the MTD image, the Volk-Costello team set out to take advantage of a principle strength in the MTD communities. The centralized hub of the University of Illinois, with 36,000 students, created an hourly potential for riders that was not being exploited by the routes he inherited, Volk says. With an annual turnover of 20 to 25 per cent of Champaign-Urbana residents, the MTD also has a greater potential for attracting new passengers each year than a more static community, a fact its managers recognize by allocating about $50,000 of the $2.1 million budget to marketing and promotion. When the Downstate Public Transit Act was passed by the Illinois General Assembly in the summer of 1974, assuring state aid to the 12 downstate (outside the Chicago area) systems, Costello says the MTD scheduled public hearings to learn what improvements Champaign-Urbana riders wanted. Because of the new state assistance, the MTD was able in January of 1975 to decrease the time between buses during the day and add buses to campus routes. Ridership went up 56 per cent. A study of the system in the summer of 1976 by an Evanston planning firm showed that residents would take advantage of evening and Sunday service if the MTD could afford to offer it. In December, the five-member MTD board decided to support a referendum to raise the tax rate from 5 cents to 20 cents per $100 assessed valuation to finance such an expansion.

"Everyone should go through a referendum or a political campaign," Volk says ruefully. "It is amazing what targeting goes on, how you seek out supporters and stay away from opponents." Volk says the local business community was one group the referendum committee stayed away from, because we've never had the kind of backing we hoped for from business as a whole." Under the direction of two part-time University of Illinois students, the referendum committee won approval of the tax hike, 4,799 to 3,769. The victory was based primarily on support from university, handicapped and elderly persons. These groups constitute the majority of riders. Following the referendum, the MTD was criticized by residents who said the vote was passed by students, who would not remain in the community and who do not pay property taxes. Volk says such criticism is "unfair" and attributes the referendum's success to the eight promises for improvements the MTD made, six of which were in operation five months after the vote. With additional local money, the MTD said it would expand service into new areas, offer earlier morning service, initiate evening and Sunday routes, provide a $50 pass good for one year ($25 for youth, handicapped and elderly persons), install wheelchair lifts on new 22/October 1978/ Illinois Issues buses, and build shelters at bustops. Except for lifts and shelters, these improvements have been made. The months from March to August last year passed in a "blur," says Volk. The system grew from 17 buses in rush hours to 34; from 16 buses during the day to 27; from 32 to 79 full-time drivers and 10 to 21 part-time; from 25 to 40 buses. Public hearings were held so residents could critique proposed routes, and changes were made when there were major complaints. The ten 17-year-old buses the MTD purchased for $100,000 had to be stripped, painted and equipped with new seats. Ridership was up immediately with the expansion and continued to increase during the winter. Costello says the system is aiming for 3 million riders in 1978.

After the expansion, Volk's salary was raised from $25,000 to $30,000, retroactive to March 1977. He and Costello, who is paid $22,000, and the MTD operations director are given company automobiles for business use. The MTD board said Volk's raise was given in part out of appreciation for good management; under his direction the MTD has attracted a larger number of passengers each year since 1974. Funding increases And true to the ridership-funding cycle, federal dollars have increased each year since the fall of 1974, when the federal Department of Transportation began funding public transit. Federal capital grants are paying for 10 new buses, which should be on the streets in late 1979, and for bus stop shelters, scheduled to be put up this summer. Older buses are being sent to be fitted with wheelchair lifts because Champaign-Urbana is one of two communities in the country to receive an Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA) grant in 1977 for such a project. Volk expects approval of another federal grant to enlarge the MTD headquarters in Urbana which the system has outgrown since it was built in 1975. The MTD also receives the standard federal allocations that cover 50 per cent of the operating deficits and 80 per cent of approved capital programs. Locally, residents have shown their support for the MTD by approving local taxes, first in the referendum that organized the district in 1971 and again in the March 1977 referendum. The 1977 referendum brings $800,000 to the MTD this year, as compared with the $180,000 it received in 1974. At the state level, more riders have not necessarily meant more funding. On the plus side, the MTD and other downstate bus lines have one third of their operating deficits paid by the state under the downstate transit act. That law allows each downstate district, with one exception, to receive an amount of up to 1/32 of the sales tax receipts collected in its district. Systems must provide local tax money to qualify. The money goes into a downstate mass transit fund from which the state's share of each system's operating deficit is drawn. The exception is the Bi-State Transit System in the St. Louis area which is funded at 2/32 and does not contribute local taxes. Volk says the act, which tunneled almost $15 million into downstate during its first three years, was a "savior" for his and other districts. But he and other downstate managers have objected to refusal by the state Department of Transportation (DOT) under Gov. James R. Thompson's administration to approve expansions under the act. As part of Thompson's program to hold down state spending, grants for expansion of mass transit services have been denied by the DOT, leaving millions in the transportation fund. The unused money has then been routed to the general revenue fund. But MTD managers say they hope H.B. 2749, sponsored by Rep. Allen F. Bennett (D., Decatur) and passed during the spring session, will make additional funds available for systems such as the MTD that elect to add routes and run buses more often. H.B. 2749 would prohibit the state from transferring unused funds from the downstate mass transit fund to the general revenue fund. Bennett and other supporters, including Volk, hope the bill will nudge the DOT to approve expansions, rather than let the unused funds — estimated to be $3 to $4 million a year — accumulate. On September 15 the governor signed the bill which became effective immediately.

Before approval of the bill, Volk had said the Champaign-Llrbana MTD expected about $200,000 in state subsidies this year, although $550,000 had been put into the transit fund for the MTD. He said that not applying the formula to deficits incurred because of expanded service has amounted to "penalizing" systems that respond to residents' demand for evening and weekend routes and improved schedules and has made it difficult for Illinois systems to expand. In addition to lobbying for changes in state funding laws, Volk has been to Washington, D.C., to lobby against a mass transit funding formula proposed by the Carter administration. Volk says the proposal, which is designed to lessen the paperwork of federal grant application, would hurt smaller systems by cutting back on capital grants. He says the plan is not expected to make it through Congress. "There is no sitting back," says Volk. "If transit is going to make it, and it is important that it does for economic as well as environmental reasons, then it has to get public support in funding. And it has to get those riders." October 1978/Illinois Issues/23

|

|||||||||||||||||||