|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Illinois judges: Too much retention and too little selection

By Paul Lermack |

|

Illinois' retention-election system was designed to protect judges from political reprisals. And it does. But, without a mechanism for assessing candidates before they enter the judicial system, there is no guarantee that the judges initially elected are qualified. And under retention, an incumbent judge is almost unbeatable. |

UNTIL 1962, the Illinois system for choosing judges was a purely political affair. Until that time, most state judges were simply chosen in partisan elections, and success usually had more to do with party backing and effective campaigning than with a candidate's capacities and background in the law. That method was clearly fraught with problems, and in 1962 a new judicial article to the state Constitution was adopted. It included a retention-election system for choosing judges in an effort to make the judicial system less political. But after 16 years of experience with this new method, it is clear that this reform has not improved the quality of the bench and that further changes are in order.

The need to separate judicial from political matters was compelling, especially in the case of circuit judges. Unlike their appellate colleagues, trialjudges sit alone, and are individually responsible to see that justice is done in their courtrooms. Since circuit courts a re unspecialized, their judges must be prepared to deal with a wide variety of cases. Complex questions of tax and corporate law as well as ordinary criminal, liability and divorce cases must routinely be decided in these courtrooms. Since few decisions are appealed, justice ultimately rests on the integrity and knowledge of the trial judges, who should be free of partisan concerns in their administration of the law.

Political pressures

Introducing political pressures into the judiciary process was clearly detrimental to the legal system. Judges, after all, are not typical public servants because they should not be expected to make all of their decisions conform to the will of the people. A judge's values and judicial philosophy could be legitimate campaign issues, of course, and it was legitimate to speak of electing a

June 1979 / Illinois Issues / 8

liberal or a conservative judge. But a judge's decision in any particular case should be based on the law alone, rather than on concerns about reelection. In addition to being instruments of the law, judges are symbols of it, and are, indeed, often the only contact many citizens have with it. Since the law is supposed to be impartial, judges must appear impartial, unaffected by ties of friendship or partisanship; and since the law is supposed to be just, judges should appear learned, wise and temperate. "In the long run," wrote former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo, "there is no guarantee of justice except the personality of the judge."

But few trial judges lived up to this high image. Dissatisfaction with existing judges and hopes of creating better selection procedures were important motives behind the organization of the American Bar Association in 1878. And as recently as 1971, investigative reporter Leonard Downie, who spent two years observing criminal courts, wrote, "there are many judges in many places who depart from the ideal in ways ranging from laughable impropriety to ruthless arrogance."

In Illinois, judgeships were traditionally poor careers. Until recently, salaries were low by professional standards and job security was minimal because terms of office were short. Too often, urban political machines used judgeships as dumping grounds for their less able retainers. Some of these machine judges knew little law. Others treated their jobs as retirement sinecures, holding court for only a few hours each day and creating wearying delays in litigation. Still others made crassly political decisions, contributing to the common image of corruption in local government. In 1962, the Institute of Public Affairs of the University of Illinois said that "the partisan method of electing judges has not worked in major Illinois cities. In some cases, it has brought the courts into disrepute."

Those few well-qualified lawyers dedicated enough to seek judicial careers in such circumstances found that the frequent reelection campaigns were expensive. Often, they were forced to seek machine patronage. Moreover, they found that their opponents often used unpopular or controversial decisions as campaign issues, thereby imposing political pressures on the judicial process. In fear of losing their jobs, even the most idealistic judges were forced to make their decisions conform to the popular will, instead of exercising that independence of judgment which the law requires.

Retention's insulation

The retention-election system, adopted in Illinois by constitutional amendment in 1962, was designed to make judges more independent of machines and the public by exempting them from partisan reelection requirements. Terms of office for circuit judges were lengthened to six years, making campaigns less frequent, and theoretically reducing the dependence of judges on political parties for campaign expenses. Instead of running against an opponent, a judge is permitted to run on his record. The voters are simply asked, on a separate ballot, whether a judge should continue to serve. If a majority (raised in 1970 to the present requirement of a 60 percent plurality) of those voting answer "yes," the sitting judge is retained for another six-year term. Since there is no opponent to focus public attention on those few decisions of a sitting judge which are unpopular or controversial, the voters are expected to base their decision on the judge's total record, and on whether it demonstrates a pattern of independence and fineness of judgment. Thus, retention elections are designed to insulate judges from hasty and ill-considered reprisals.

|

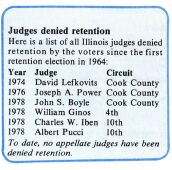

The reform has succeeded, but much too well. Judges have become so insulated that it is almost impossible to remove any of them, even the most incompetent. In 16 years to date, only six sitting judges have been turned out of office. Of 524 judges running for retention, in other words, 518, or 99 percent, have been retained. Many of these had been found unqualified by bar associations, or were opposed by other officeholders or newspaper editorials. For example, the Illinois State Bar Association, which rates downstate judges, recommended against the retention of 10 in 1972. But all were retained. Between 1970 and 1978, the State Bar Association recommended against retaining 33 judges. Thirty-one of these 33 were retained. In 1974, David Lefkovits, a 21-year veteran of the Circuit Court for Cook County, became the first Illinois judge to lose a retention election. Lefkovits, then 74, was one of eight judges labelled "clearly unqualified" by the Chicago Tribune and opposed by the Chicago Bar Association. Although the seven others were retained, the Tribune expressed optimism that the voters were finally learning how to use the new form of ballot, and predicted that they would remove bad judges more readily in the future. |

|

But this has not happened. In 1976, only one judge was removed. Joseph A. Power, chief judge of the Circuit Court for Cook County and a close friend of Mayor Richard J. Daley, had been accused of political favoritism during the special grand jury investigation of the 1969 police raid on the Chicago Black Panthers headquarters during which two persons were killed. He had also been defeated in a recent election bid for the Democratic nomination for a vacant seat on the Supreme Court. The Tribune, now much more pessimistic, noted that three other Chicago judges

June 1979 / Illinois Issues / 9

had been retained despite a "consensus of informed opinion against them" and editorialized that Power was defeated only because his political bias had become unmistakably visible. Since no partisan opponents exist in retention elections to publicize the records of the incumbents, the Tribune concluded that there is no way for the voters to rationally assess them: the voters will tend to retain any sitting judge unless political notoriety makes his bad record inescapable. In this "parody of normal elections," as the Tribune described it, a judge who is incompetent but quiet is unbeatable.

Boyle's defeat

The defeat in 1978 of John S. Boyle, Power's successor, tends to corroborate this view. Boyle was politically notorious. The Chicago Council of Lawyers, which recommended against his retention, accused him of using the chief judge's assignment power to place politically sensitive cases in the hands of judges who were responsive to the influence of the Cook County democratic machine.

But while these cases seemed to mark extremes in which clear abuses of power had awakened a normally apathetic electorate to "recall" the perpetrators, the defeat in 1978 of two 10th Circuit judges is less easy to explain. Although each had provoked opposition, neither was as controversial or political a figure as Boyle or Power. Albert Pucci of rural Putnam County was 68 years old and had been ill. And Charles W. Iben of Peoria was accused of "arrogance" and lack of judicial temperament.

The case against Iben was given focus by the Peoria Journal Star, which published four editorials on the subject. These editorials provoked comment, exchanges of letters and the interest of other mass media. Iben was accused of insensitivity, of inattention on the bench, of holding sloppily informal court sessions, of holding negotiating sessions with attorneys in his chambers out of hearing of the litigants in the case (a possible violation of judicial ethics), and of keeping short hours.

The Journal Star acted as an old-fashioned crusading newspaper. But it was not wholly disinterested. Iben had the reputation of being a liberal judge and of setting low bail amounts in criminal cases. In this, his values were somewhat out of line with the relatively conservative circuit in which he worked, and with the Journal Star itself. The newspaper opposed him out of philosophic conviction. In a sense, by publicizing the worst aspects of Iben's record, it performed the function usually performed in elections by the opponent. Without this focusing of opinion by the media, it is doubtful that any sitting judge can be defeated. Bar associations try to draw public attention to poor judges by making public recommendations on retention. But their influence is limited. Of 16 downstate judges opposed by the Illinois State Bar Association in 1978, for example, 14 were retained. One of them, Charles M. Wilson of rural Toulon, best summarized the influence of the organized bar: "The laymen don't care what the lawyers think."

One suggestion for improving the performance of the retention-election system is to encourage other public officials to publicize judicial incompetence. Sheriffs, public defenders and especially state's attorneys are ideally located to compare judges and to recognize poor performance. Moreover, since they regularly work with judges, they are likely to judge performance on the basis of the total record and not by a single controversial incident. But public officials are reluctant to speak out against bad judges, in part because legal ethics forbid speaking derisively about a sitting judge, and in part because state's attorneys fear reprisals from judges who are retained over their opposition. Perhaps most important, when such opposition occurs, the public seems to perceive it as "political" and to discount it. For example, McLean County State's Atty. Ronald Dozier actively opposed the retention of llth Circuit Judgt Keith Campbell in 1978, accusing him of "irrational and bizarre behavior" on the bench. But Campbell was retained.

Other states have had similar experiences. For example, in 1972 the Chicago-based American Judicature Society, which favors the retention-election system, surveyed the 11 states then using it and found that only four judges had been defeated that year. The society commented that retention elections do not "assure life tenure," but acknowledged that the present system makes it difficult to unseat incumbent judges, regardless of the inadequacies in their performances.

The purpose of the retention-election system is, of course, to protect judges from capricious and arbitrary attacks based on political grounds. The irony is, however, that this insulation from politics has apparently not improved the quality of the bench, if recent elections are indicative. Of the judges retained in 1978, for example, Sam Harrod III of the 11th Circuit had been disciplined by the Courts Commission for arrogant conduct on the bench (although the punishment was later set aside by the Illinois Supreme Court on a technicality). Also suggestive is the fact that 12 of the 23 judges retained in the Chicago area in the last election had been found unqualified by the Chicago Council of Lawyers. The Judicial Inquiry Board, created by the 1970 Constitution to deal with complaints against sitting judges, has heard charges ranging from fixing traffic tickets to collusion with organized crime.

When a circuit or appellate judge is defeated, a temporary replacement is appointed by the Illinois Supreme Court. At the next general election, a permanent replacement is elected on a partisan ballot -- that is, on the basis of party support or public appeal, rather than legal credentials. The retention system, which makes it difficult to remove a sitting judge, has not been coupled with some mechanism for assessing the qualifications of candidates before they are chosen. In partisan elections, there is no way for candidates to demonstrate anything resembling judicial temperament; since merit does not descend on new judges like Elijah's

June 1979 / Illinois Issus / 10

*REMAINING PAGES MISSING*

|

|