|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Illinois pension funds: A fictional crisis?

By A. James Heins and William R. Bryan |

Alarmists say the state must fully fund its employee pension plans or it will default in meeting payouts at some future date. But using personal income as a yardstick, the pension debt is well within safe limits. And as a percentage of personal income, the unfunded pension liability has been declining. |

AS INFLATION rates rise and as larger proportions of the American population join the ranks of the retired, there is growing concern over the ability of pension funds to meet their obligations as they come due. In Illinois, as in several other states, there has been a vigorous effort by teacher organizations to move the state towards "full funding" of retirement funds to insure continued incomes for retirees (see Illinois Issues, July 1977, pp. 10-12). Nationally, sharp increases in Social Security taxes have been implemented in recent years in anticipation of prospective deficits in the sytem's ability to meet its obligations in the future.

Some of the concern over potential defaults in pension systems is, of course, justified. But a close examination of the pension situation suggests that panic is unwarranted and that alarmist views on the matter are based on a fictional crisis that is not likely to occur.

Like all employers, the State of Illinois makes contracts with its employees, exchanging wages and fringe benefits for employee services. The largest of these benefits is the pension plan, under which employees make contributions to a fund administered by the state, while the state in turn agrees to pay employees certain lifetime benefits at their retirement.

Given assumptions about mortality and interest rates, the state can project the present value of its promises to retirees in the future. Currently there is a gap of $3,317 million in Illinois between that value and the assets of the pension funds now on hand. That "unfunded accrued liability" of the pension system may be considered an "implicit" debt of the state, in contrast with the "explicit" debt of the state represented by its bonded indebtedness. Seen in this way, any increase in the scale of retirement benefits for Illinois employees can be viewed as an implicit increase in state debt -- a consummation not devoutly wished by tax reformers or taxpayers.

The apparent dilemma, then, seems clear. Does the state increase its appropriations to insure "full funding" of the pension obligations to retired employees? Or does it simply default on those obligations if the demand on the fund exceeds its resources at some time in the future? Yet while those seem to be the choices, neither extreme is inevitable, and neither seems likely, given the facts of current and projected elements of the system.

Currently, first of all, the state contributes to its pension funds on a "pay-as-you-go" basis. This means annual contributions by the state are approximately equal to the pension benefits paid annually. And while the payout for the State Universities Retirement system in 1976, for example, was $31 million and the appropriations were only about $29 million, that year was unusual. In other years, state appropriations have actually exceeded the pension payout, which suggests the viability of the current system.

But proponents of full funding point out that the unfunded accrued liability of Illinois pension funds can change from year to year. Salaries, benefit scales, employee contributions, mortality rates and the number of state employees are all subject to changes which may affect the value of the unfunded accrued liability. Some employees naturally fear the variability of these factors, and they view an escalating liability as a threat to the state's will or ability to make good its promises. They argue that it is one thing for the state to cover a $2 million deficit in 1976 (which it could do from pension system reserves), but quite another to meet an estimated $420 million appropriation for pension payouts in the year 2000.

That $420 million estimate, however, is highly suspect, dependent as it is on current assumptions about inflation, public employment, benefit levels and wages. Those projected factors also affect taxpayers' capacities to meet pension payouts, and they do not reflect such developments as the current taxpayer revolt and its likely impact on public employment.

|

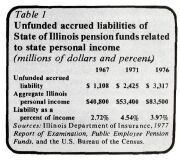

It is treacherous, in other words, to base pension policies on speculations about such uncertain variables. An evaluation of current state policy in the-light of recent trends in Illinois pension liabilities and taxpayers' capacities as measured by income should yield more reliable projections, especially if these factors are examined in connection with all state debt. Such an evaluation reveals the fictional nature of the current "crisis" and suggests that the Illinois pension system is currently viable and should remain so in the foreseeable future. The data in table 1 reveal one of the hopeful signs. The figures show that while the percentage of liability for the pension fund grew from 2.72 in 1967 to 4.54 in 1971, the trend was reversed by 1976, when the percentage dropped to 3.97. This recent trend, which shows signs of continuing for a long term, suggests that the implicit debt of the pension fund is actually declining rather than escalating as a percentage of the |

|

July 1979 / Illinois Issues / 19

|

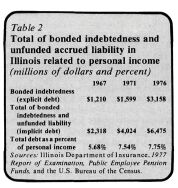

aggregate personal income of Illinois residents -- the most commonly used measure of taxpayer capacity. The challenge, of course, is to ensure that the trend continues. Some proponents of full funding for the pension system argue that the state should make its implicit debts explicit by floating bonds and paying the proceeds over to the pension fund. But those funds would then be used by pension fund administrators to purchase the explicit debt of other entities, mainly private corporations and the United States government. The net effect of such a policy is questionable, however, since it is doubtful that the explicit debt of those entities is "safer" than the implicit debt of the State of Illinois. Moreover, as table 2 suggests, the bonded ("explicit") indebtedness of the state has been growing at a much faster pace than unfunded pension liabilities since 1971, although the total as a percent ot Illinois personal income has changed only slightly. Once again, the data support the continuance of the current "pay-as-you-go" system in Illinois, which has so far kept the implicit debt of the state within narrower bounds than the explicit debt. |

|

|

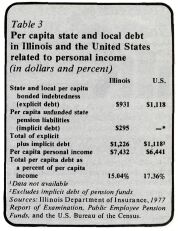

The question remains whether a total state debt amounting to 7.75 percent of the aggregate income of Illinois residents is an undue burden on taxpayers. Table 3 suggests that it is not, when Illinois is compared to the rest of the nation. The data indicate that the total debt of all government units in Illinois, including the implicit debt represented by unfunded state pension liabilities, represents a smaller claim on the income of Illinois residents than the claim of explicit debt alone for all states on total U.S. personal income. Even when local pension fund liabilities are included, Illinois' position looks strong, since even then the per capita total debt of all units of government comes to $1553, which comprises only 20.93 percent of Illinois personal income. All signs and recent trends, in other words, suggest that total public debt in Illinois is not out of hand and that the pension "crisis" is fictional, not real. But complacency could lead to chaos, and the position of the pension funds must |

|

July 1979 / Illinois Issues / 20

be monitored on a continuing basis, especially since it is not yet part of a rational debt management policy which encompasses both explicit and implicit debt.

While the current "pay-as-you-go" system is not tied to an actuarial computation of the present value of future benefits, it has -- coupled with pension contributions of those currently working -- so far had the effect of reducing the amount of unfunded liability (implicit debt) relative to taxpayers' income since 1971. Measures must be taken to continue that trend.

One such measure, of course, would be for the General Assembly to mandate debt limits by requiring either reduction in bond flotation or increased contributions to pension funds to lower implicit debt, if total debt exceeded a specific percent of the most recent years' income. Such schemes are cumbersome, however, and constitutional and statutory limitations on a state's indebtedness frequently lead to costly evasions.

Simpler and saner, we think, would be a system which would require the governor, as chief budget officer of the state, to provide detailed information on the debt position of the state, implicit as well as explicit, as part of the state budget. In addition, the governor should be required to detail the steps being taken to keep that total debt within bounds. Given the taxpayers' sensitivity to government spending, it is sufficient that the public and the legislature be informed about the current debt position of the state at budget time so that that position can be related to recent tends. Wide dissemination of that information should insure fiscal responsibility and the avoidance of fictional crises.

A. James Heins is a professor of economics and William R. Bryan is a professor of finance at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

July 1979 / Illinois Issues / 21

Pension action: No cuts, few increases By John E. Williams

THE LACK of sufficient funds in Illinois' nearly 500 state and local public pension systems makes more and more people wonder if future pension obligations will be met. Most pension experts consider a pension system that is 60-80 percent funded as fiscally sound. None of the state-funded systems top the 50 percent funding level; in fact, some are below the 40 percent mark. Although pension systems at the municipal level tend to be better funded, police and firemen pensions cost some cities as much as 58 percent and 70 percent, respectively, of what is paid out in salaries, according to Larry Frang of the Illinois Municipal League. This is a situation, according to Frang, cities cannot endure.

How the financial picture of public pensions in Illinois can be improved is a politically tough question. Through higher taxes, freezing of benefits or increasing contribution rates? All of these ways are unlikely. Tax limitations that would prevent increases in taxes to pay for more funding are now a real possibility. Unwilling to idly sit by watching their pensions eaten up by inflation, pensioners and soon-to-be pensioners will undoubtedly demand more from legislators. And since the contribution rate by public employees is already high in comparison to other states' public pension systems, substantial contribution hikes for employees are unlikely.

How did Illinois get itself into such a mess? Sen. Karl Berning (R., Deerfield), member of the Senate Pensions, Personnel and Veterans Affairs Committee, contends the "state has been derelict" because of "inadequate funding by administrations" and the "ill-advised . . . generosity of the General Assembly" that resulted in the liberalization of pension benefits. Frang echoes Berning's explanation in accounting for the poor shape of the local pension systems by saying "cities haven't put in what they should have" and have approved "new benefits . . . [which] increased the unfunded accrued liability."

The problem created by inadequate government contributions, usually an amount that only covers going pension costs, is that increasingly bigger amounts of money must be doled out to pay future going costs as more people retire. The extension of benefits adds to this spiraling cost. In a sense, government is only buying time before it must eventually pay its bill -- if it is able.

However, hard-liners on minimizing pension costs contend pensions were never intended to cover all living expenses during retirement years. Sen. Berning believes pensions are only an "auxiliary" form of benefits to heJp retired persons take care of themselves, not a form of "welfare," an attitude he says more and more people are taking. In times of high inflation, pensioners and taxpayers need to be "educated," according to Ed McCreight, director of research at the Taxpayers' Federation of Illinois. McCreight believes people must learn that pensions should be supplemented with other plans, e.g., tax annuity tax funds, which would provide another source of income during retirement. And besides, McCreight says most public employees enjoy "liberal" benefits compared to the pension of the average working man.

Despite the gloomy status and seeming lack of recourse, the fiscal soundness of the pension systems has been improving in the last few years. Funding levels have been edging upward in the state-funded systems, and municipalities have been meeting funding requirements set by the Department of Insurance. The change, according to Betty Rae, executive director of the Illinois Pension Laws Commission, is due to legislators who are becoming "more responsive" to cost concerns. Most would agree with Rae's assessment. Aside from political considerations, cost is the overriding determinant of the success or failure of proposed pension legislation.

Greatly influencing legislators' decisions is the Illinois Pension Laws Commission. If a bill doesn't "bring a system in line with other systems" or "if the funding is not there, we're against it," Rae said, explaining the basis on which the commission makes its recommendations of approval or disapproval to the pension committees. Unfavorable positions on bills by the commission have undoubtedly helped legislators resist lobbying pressures for more benefits by employee organizations.

Cost consciousness on the part of the legislature and the passing of the buck to the commission account for the paucity of benefits passed in recent sessions. The limited legislation likely to become law this session includes amending present statutes to put the state in line with federal laws by allowing persons on maternity leave to continue to participate in the pension system and raising the compulsory retirement age from 67 to 70 years of age. Other bills that would raise the floor for survivor's benefits and make administrative changes peculiar to specific systems could also very well pass. One measure which is still alive could be interpreted as an exception to the anti-benefit mood: Senate Bill 375, sponsored by Sen. Jack Schaffer(R., Crystal Lake), would allow teachers to retire early without penalty by making a one-time contribution to the system. As of May 25 the bill was in the House on first reading.

The unofficial moratorium on increasing pension benefits is obviously viewed negatively by employee organizations. Their emphasis on benefits is understandable since they are probably less concerned about the solvency of the government's pension reserve in the long run than immediate benefits to pensioners and anticipated pensioners.

On the other side of the fence are the hard liners seeking legislation that would freeze or reduce benefits. Their legislative efforts have been unsuccessful to date. For example, S.B. 1360 sponsored by Sens. Berning and David J. Regner (R., Mount Prospect), would, among other provisions, tighten up benefits by increasing the age and length of service requirements for police and firemen hired in the future. However, this provision was deleted, leaving the funding provision that would require the amortization of the unfunded accrued liabilities over a 40-year period. The bill is in the House on first reading.

Despite claims by fiscal conservatives that one can't have both extended benefits and increased funding, Rep. Larry Stuffle (D., Charleston) said what is needed is a "reasonable" approach between "needed benefits" and "what must be put in." Stuffle and representatives of employee organizations maintain that the present level of benefits are not "unreasonable" and some new benefits are warranted.

Stuffle's middle-of-the-road approach appears to be that of the General Assembly. Whether this approach is sufficient to offset inflation to the satisfaction of pensioners and, at the same time, keep the systems solvent is an open question. But, at least, Sen. Berning says he's "encouraged" about the pension situation because of the position of the commission, the cost-conscious attitude of more members of the General Assembly and passage by the Senate of S.B. 250 which would increase the rate of the state's contribution by 5 percent of payroll every fiscal year.

Interestingly enough, McCreight thinks 50 percent funding is adequate for pension plans and that a higher level of funding would only serve as an incentive for members to seek a "basketful of benefits."

July 1979 / illinois Issues / 19-20

|

|