|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

| Ticket splitting: an ominous sign of party weakness |

|

By David H. Everson and Joan A. Parker |

| More and more voters are rejecting the straight-party lever. While this increase in "independents" may mark a new sophistication in the electorate, it may also threaten the legitimacy of the political system. |

THERE CAN be no argument that more and more Illinois voters are splitting their votes between Republican and Democratic candidates. All the evidence suggests that fewer Illinoisans pull the straight party lever in the voting booth; more voters call themselves independents, ignore traditional party organizations and pay more attention to candidates' stands on single issues than to broad-based party platforms.

Some see this rejection of party ties as a hopeful sign. They assume that this new voter independence indicates a new rationality and sophistication on the part of the electorate. They assume that voters who ignore party labels are more enlightened and better informed than straight-ticket voters.

To the degree that ticket splitting marks decline of party power, however, the trend may be ominous and a serious threat to the effectiveness and legitimacy of the political system. Weaker parties, first of all, cause lower voter turnouts. They also pave the way for political fragmentation and undue influence by special interest groups. An absence of strong political parties, in short, may lead to an absence of clear responsibility for public policy and to political chaos for the nation and the state.

One general sign of ticket splitting is the divided control between parties of the major state executive offices, according

August 1979 / Illinois Issues / 9

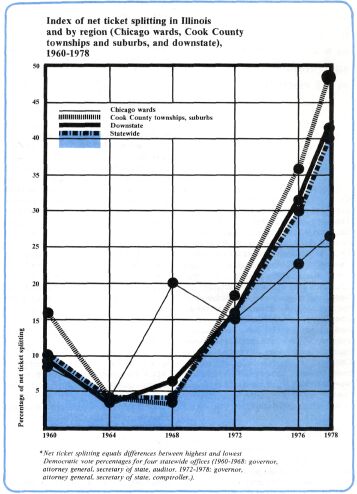

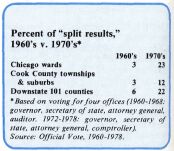

to W. DeVries and V. L. Tarrance in The Ticket-Splitter. And in Illinois, the major parties have divided control of the top four state offices since 1960. Moreover, there is an increasing pattern of "split results" in the various constituencies throughout the state that vote for these offices. For example, a ward in Chicago might vote Democratic for secretary of state and comptroller, and then vote Republican for governor and attorney general. The decade averages show major increases in "split results" in each area of the state -- the Chicago wards, the Cook County townships and suburbs and in the 101 downstate counties. Most astounding is the seven-fold increase in "split results" in the wards of Chicago.

The last sweeps

The increase in "split results" demonstrates that voting patterns in the state have changed since the days when a full slate of one party's candidates was elected. The last time the Republicans won all the statewide executive offices in one election was in 1956 when William G. Stratton won his second term as governor, along with John Wm. Chapman as lieutenant governor, Latham Castle as attorney general, Charles F. Carpentier as secretary of state (all reelected from the previous term) and Elbert Sidney Smith as auditor of public accounts. The Democrats' last sweep of these offices was in 1948 when Adlai E. Stevenson II was elected governor along with Sherwood Dixon as lieutenant governor, Ivan Elliott as attorney general, Edward J. Barrett as secretary of state and Benjamin O. Cooper as auditor of public accounts. But from the 1960 election on, results have been split between parties for the four state offices analyzed here.

No data exist that can exactly measure the degree of individual ticket splitting, but estimates can be made based on votes cast. A frequently used technique known as the "Burnham measure" can be adapted to come up with an index of ticket splitting. For example, if results showed the Democratic candidate for governor received 75 percent of the vote statewide while the Democratic candidate for secretary of state received 25 percent of the vote, the inference is that 50 percent of those who voted for both offices split their tickets. More individual ticket splitting undoubtedly occurred, so the 50 percent is a "net" index of ticket splitting. A specific application of the Burnham measure to the 1978 general election shows that the percentage of Democratic votes cast for each office were: Michael J. Bakalis for governor, 40 percent; Alan J. Dixon, secretary of state, 74 percent; Richard J. Troy, attorney general, 35 percent; and Roland W. Burris, comptroller, 53 percent. By subtracting the lowest value (Troy's) from the highest value (Dixon's), the ticket splitting net index is obtained: 39.

The graph traces the increases in "net ticket splitting" in Illinois from 1960 to 1978. The statewide data reveal a fourfold increase from 1960-1978, with the sharpest rise occurring after 1968. The graph reveals a similar pattern in each of the areas of Cook County. It is equally important to note that ticket splitting is up substantially in the wards of Chicago, the former bastion of the Democratic party.

This upsurge in Illinois seems to reflect a national decline in the power and importance of political parties. Rampant ticket splitting means that the parties are unable to inspire loyalty in their traditional followers, and that more and more "independents" are voting in every election. The causes for this weakening of party influence are many, and the erosion of party power has been a long and steady process.

|

Around the turn of the century, a wave of antiparty reform spirit swept the U.S. and resulted in legislation which significantly weakened party organizations. The direct primary, an effort to take political nominations out of the hands of the "bosses," for example, had the effect of eroding the capacity of party organizations to control their own affairs. The potential for a party boss to abuse power was thereby limited, but the party's base of power was also weakened.

The diminishing hold |

|

In Illinois, the weakening of the hold of party on the electorate began in the late 1960's; however, the evidence is that

August 1979 / Illinois Issues / 10

the 1972-1976 period was critical. Previously, the races for statewide office (especially governor and secretary of state) had been close, partisan contests. In 1972, the maverick Democrat, Dan Walker, won the nomination for governor, beating the organization-endorsed candidate, Paul Simon. This upset triggered a series of other events resulting in the unusual 1976 and 1978 elections. Walker's tenure as governor was marked by sharp conflict with the Chicago organization and confrontation with the Democratic legislature. An organization-backed candidate, incumbent Secretary of State Michael J. Hewlett (a very popular statewide votegetter in all his previous elections) defeated Walker in a bitter Democratic primary in 1976. But Howlett's reputation was tarnished as a result of that very divisive primary, and he lost the general election by a record vote to another antagonist of the Chicago organization, former U.S. prosecuter James R. Thompson. In 1978, Thompson was reelected by the biggest landslide in Illinois history.

It should here be noted that a popular downstate Democrat, Alan J. Dixon, has emerged as a counterpart to Thompson on the Democratic side. In 1976 when he first won the office of secretary of state, Dixon polled only 93,000 fewer votes than Thompson; in 1978 Dixon actually received more votes and a greater winning percentage.

Partyless politics

One could argue that the splits in the Democratic party and the personal popularity of candidates such as Thompson, Dixon and Republican Attorney General William J. Scott, explain the increase in ticket splitting in Illinois. But these results seem consistent with a national trend which signals a sharp decline in party power. The specific events in Illinois politics may have increased the severity of the trend here; but the causes for the national decline are also found in Illinois. Candidates such as Walker and Thompson have used the mass media and effective manipulation of political symbols to broaden their appeal beyond party and to "presidentialize" Illinois electoral politics. And Illinois' own political scandals have, of course, added to the distrust of parties. In addition, the political climate of the 1970's is such that in Illinois, as in the nation, the ballot splitter is regarded as more discriminating and sophisticated than the straight-party voter.

It is impossible to completely disentangle the various political and psychological explanations for the weakening influence of parties on the vote for major statewide offices in Illinois. The question is whether the decline is temporary, a product of the unique confluence of events of the early and mid-1970's in the state, or whether it represents a trend toward partyless politics in the future. There is no certain way to decide this question now. The findings, however, are consistent with national trends. Illinois is extreme in its tendency to split tickets, but the state is not alone.

The enlightened voter

Many people believe that strong political parties, and especially strong partisan loyalties, are unhealthy for a representative democracy, and irrational for the individual. To these observers, the decline of party suggested by increases in ballot splitting is a sign of a new maturity and rationality in the electorate. It is a real benefit to Illinois politics, they believe. For example, the authors of a major work on ticket splitting conclude that "these are the most discriminating voters in our democratic system and offer the best hope for the revitalization of our unique American democracy"(DeVries and Tarrance).

From another perspective, however, this new voter independence suggests that substantial increases in ticket splitting are detrimental to effective political democracy in the nation and Illinois, and that weak parties may in fact jeopardize the effective ness and legitimacy of our political system. It seems clear, first of all, that once party weakens its hold on voters, other factors must increase in influence on voter choice. The ideal is, of course, the "issue-oriented" voter who takes the trouble to read about and listen to the candidates before making enlightened choices.

Unfortunately the ideal is all too rare, and "issue-oriented" often translates into "single-issue" to describe the voter who makes choices on the basis of a single, intense preference on such issues as birth control, laetrile or one of the myriad causes which vie for public attention. Such voters disregard the full record of candidates or parties and focus instead on a single plank from a broad platform. And when narrow concerns combine with the "new politics" of mass media and image hype for candidates, party ties and policies become even less important to more and more voters.

The total effect of these changes is to make the outcome of Illinois elections more erratic and to make landslides much more common. In the 1960's, Illinois experienced only one statewide landslide election (the unusual presidential election of 1964), while there have been 10 such elections in the 1970's. Statewide elections are less competitive and those trends are associated with declining turnout in Illinois elections (Illinois Issues, June 1979, pp.4-7). Lowered voter turnout increases the potential influence of intense, single-issue voters, and also weakens the capacity of those elected to claim a majority mandate. At some point, the very legitimacy of the political system may be in doubt because of lack of participation.

At the level of legislative elections, the decay of party competition means that incumbency reigns supreme. Consider

August 1979 / Illinois Issues / 11

the Illinois Senate elections in 1978 when the success rates of incumbents seeking reelection was 97 percent. This compares favorably with the success rates of U.S. House incumbents and is significantly higher than the rates for U.S. senators. Only four of 40 Senate races in Illinois in 1978 were competitive enough for the challenger to receive at least 45 percent of the vote.

The atomization of politics

The effect of volatile statewide elections and the safety of legislative incumbents is to create a high potential for divided government. As we have seen, a divided executive branch is now the rule in Illinois. However, we also may anticipate that landslide elections of governors will not automatically create supportive legislative majorities. Divided government creates the potential for policy stalemate especially if the party leaders in the legislature are not able to develop and maintain legislative compromises with the governor. Just as party has been a major cue for voter, so too has it served as an organizing device for the legislature. The dramatic weakening of the party in the electorate of Illinois is bound to have an effect on the bonds of party in the General Assembly. For example, one may anticipate some weakening of the strong cohesion of the Chicago Democrats.

Without parties supplying the strength of compromise, the influences of interest groups on the legislative process is likely to be magnified. If the above analysis of "single interest" voting is correct, then the influence of interest groups on the General Assembly will be enhanced.

In short, the decline of party threatens the cohesion necessary for effective legislative decision making by weakening (or removing) the basis for leadership and compromise without providing any effective substitute. The result is the atomization of politics in Illinois. The price of rational individualism may be ineffective and ultimately illegitimate government in Illinois.

David H. Everson is associate professor of political studies and director of the Illinois Legislative Studies Center at Sangamon State University. He is the author of a forthcoming book on American political parties.

Joan A. Parker is associated with the Center.

August 1979 / Illinois Issues / 12

|

|