|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

| No fault tug-of-war: trial lawyers pull hard for status quo |

|

By Martha Collins |

| No-fault auto insurance has been shown in some states to be cheaper, more efficient of courtroom time and less demanding of claimants. But pure no-fault auto insurance eliminates the need for suit, and law firms which rely on such suits don't like that. |

THE IDEA of no-fault automobile insurance is simple. Policy holders involved in automobile accidents are reimbursed by their own insurance companies for medical expenses, income loss and other economic losses specified in the policy contract regardless of who was at fault for the accident. All 50 states have at least considered the issue since 1967; but only 16 have so far I approved no-fault laws, and Illinois is not among them.

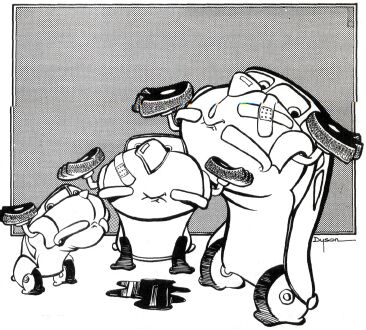

While the idea of no-fault is simple, the politics of no-fault are not, and therein lies the rub for its advocates. In Illinois, the issue has become a perennial I and expensive tug-of-war. On one side are the insurance industry, the Department of Insurance and many consumers; on the other side are the trial lawyers and a small but weighty group of legislators. The latter group, which seeks to maintain the current system of liability insurance, has so far held its own despite numerous concerted efforts by the no-fault forces.

Given the provisions of most no-fault plans, it is easy to understand the opposition by the Illinois Trial Lawyers Association (ITLA) and the Illinois State Bar Association (ISBA). "Pure" no-fault insurance, for example, provides for reimbursement for medical expenses, salary loss, property damage, death benefits and other expenses to the insured involved in the accident. And since there is no need to establish who was at fault in order to be reimbursed, the right to sue for damages is eliminated. Legal firms which rely heavily on such suits would obviously deplore such a plan, since it would sharply reduce their potential pool of clients.

Limited no-fault

"Threshold" no-fault insurance, another variation, allows limited rights to sue as specified in a given law. Most commonly, threshold plans restrict the right to sue for noneconomic damages or "pain and suffering" and are limited to accidents resulting in death or permanent disfigurement or injury.

The Oregon plan (which some call "phony" no-fault) provides the benefits of the pure version, but it places no limits on the right to sue. It derives its name from the state in which it was first enacted in 1971, and it is clearly most palatable to lawyers' groups because it preserves their opportunities for legal action as a result of automobile accidents.

The tumultuous history of no-fault efforts in Illinois also goes back to 1971, when the General Assembly actually passed a bill to institute the plan. That bill (S.B. 976) was later declared unconstitutional by the Illinois Supreme Court on four specific counts:

1. The provision for compulsory arbitration between insurance companies for claim disputes involving $3,000 or less was said to deny certain individuals the right to a jury trial.

2. The provision for payment of arbitration fees by a losing party was held to violate the constitutional ban on fee officers in the judicial system.

3. The provision which permitted new evidence in the review of a prior decision reached through arbitration was held invalid.

4. The provision imposing specific restrictions on recovering damages for pain and suffering as a result of an accident were found to be discriminatory against the poor.

August 1979 / Illinois Issues / 13

The ITLA initiated the suit against the 1971 act, and it had reportedly spent $100,000 in an unsuccessful attempt to defeat the no-fault bill while it was going through the legislative process. That same year, the ITLA also set up an office in Springfield, presumably to be closer to the lawmaking arena.

Legislative setbacks

Despite that setback, no-fault proponents have remained persistent and have introduced legislation in nearly every subsequent year. Several such proposals were considered in the 1972 legislative session, but none was approved by both chambers until 1973, when Sen. Harris W. Fawell (R., Naperville) introduced S.B. 187 which was backed and virtually drafted by the ISBA. But Gov. Daniel Walker vetoed the bill because it had no threshold limitations on the right to sue.

The ISBA's active support of the "phony" no-fault "Fawell bill" in 1973 contradicted the argument of its parent organization, the American Bar Association, which at the time contended that any no-fault system would lead to a 20 percent increase in premiums. Without restrictions of any kind for suing, the Fawell bill would have confirmed the American Bar's argument.

A short-lived resuscitation of no-fault insurance took place in the Senate in 1974. And in 1975, S.B. 1500, with a threshold provision of a $1,000 minimum for expenses before any suit for pain and suffering could be filed, was again amended into an "Oregon plan" in the House.

Rep. Charles Fleck(R., Chicago), who sponsored the Oregon amendment, claimed the original bill's provisions denied "equal protection for Illinois drivers", especially the poor who "could not remain in the hospital long enough to reach the medical expense limit" that had to be reached before legal action could be taken. It should be noted that in addition to being a legislator, Fleck is also a trial lawyer.

More recently, three no-fault bills have been introduced in the 81st General Assembly. One was tabled and two were placed on interim study, meaning they could be revived next year, although neither the ITLA or the ISBA gives them much chance for surviving, according to their spokesmen. But the sponsors of the bills now on interim study appear optimistic about the future of their proposals, and both said they plan to hold public hearings to drum up support for no-fault insurance.

One of the proposals, H.B. 1631, sponsored by Rep. Gerald A. Bradley (D., Bloomington), is a threshold no-fault plan. It provides for medical expense reimbursements up to $25,000 and for salary loss reimbursements and loss of service payments up to $20 each day to a maximum of three years from the date of the accident. Bradley's bill also includes a $1,500 death payment and the right to sue for noneconomic damages limited to cases involving death or serious and permanent disfigurement and injury.

Sen. John J. Nimrod (R., Park Ridge) is sponsor of S.B. 1385, with similar benefit provisions, except for a $300,000 maximum for reimbursement for medical expenses. Nimrod's bill also sets unusual conditions for legal recovery of accident-related expenses. One insurance company may recover payments made to its policyholder in excess of $25,000 from the other insurance company which holds the policy of the person at fault for the accident. Recovery can either be accomplished in court or through an arbitration procedure approved by the director of insurance.

Precarious fate

The fate of both bills is precarious, according to one insurance company lobbyist who has closely followed the fortunes of no-fault in recent years. The cause lost one of its biggest boosters in the Senate in Robert T. Lane(D., South Holland). Lane, who sponsored a no-fault bill in the 80th General Assembly and was also chairman of the Senate Insurance and Licensed Activities Committee, was defeated in his bid for reelection last November.

Lane left behind S.B. 1017 which passed in the Senate in 1977 with 39 votes and was defeated by one vote in the House. The bill in its original form was very similar to Bradley's bill.

According to Lane, the bill's defeat in the House was a blessing in disguise because an amendment added by that Chamber had turned it into an Oregon plan. The House amendment, Lane said last fall, "would have removed all restrictive conditions for which an insured could file suit for damages for personal pain and suffering."

Lane claimed the amendment was added to satisfy the trial lawyers' objections. Trial lawyers or attorneys play a considerable part in claim settlements, unless the law restricts the right to sue, he explained. He contends that the amended bill would have eliminated the major benefits of no-fault insurance -- a reduction in court cases and costly attorney fees.

The insurance industry was also relieved that the bill with the Oregon amendment did not become law. According to one spokesman, insurance companies are generally opposed to no-fault insurance without tort restrictions. For insurance organizations, an arrangement that would require them to reimburse all auto injury claims regardless of fault and to make additional payments of damages awarded by court action would lead to astronomical costs. The consumers would ultimately pay for that cost in higher premiums, he said.

According to Lane, the trial lawyers stand against any kind of threshold restrictions on the right to sue has been uncompromising. As the insurance industry spokesman pointed out, approximately 40 percent of the legislators in each Chamber have private trial practices. If these 40 percent were to vote in favor of a pure or threshold no-fault law, they would be voting against their personal interests. Their law practices depend on a liability insurance system.

Advocates of no-fault in Illinois have another strong supporter in Jeffrey O'Connell, a University of Illinois law professor who is known as the father of

August 1979 / Illinois Issues / 14

the concept. O'Connell points to a number of benefits which would accrue both to individuals and to the court system if a no-fault plan were enacted:

- every person injured in an auto accident would be assured of some reimbursement without the need to prove someone's fault;

- minor injury claims would no longer be overcompensated and serious injuries would receive greater compensation;

- claims would be settled promptly because the time-consuming task of establishing contested fault would be eliminated;

- a smaller proportion of each premium dollar would go toward legal fees and insurance overhead costs;

- the number of lawsuits related to auto accidents would decline, relieving the congestion of court schedules;

- the cost of auto insurance would be contained, if not reduced.

Disputable premiums

The case of Massachusetts, which enacted its bill in 1971, illustrates the potential which no-fault may hold for reducing premiums on auto insurance. The first two years of no-fault in that state led to a series of premium cuts totaling 70.2 percent. And during the first year, the total amount paid for reimbursement of bodily injury claims was $45 million, or half the amount paid out the year before under the liability system.

The long-range effect of no-fault insurance on premium rates would not, however, be a continuous nose dive. But an overall comparison of no-fault rates with liability rates shows the former to be lower or to rise more slowly. According to O'Connell, State Farm Mutual Company's automobile insurance rates have increased less in most states with a no-fault law than in most states still under a liability system.

Clyve Topol of ISBA disagrees with that finding, saying there is no conclusive evidence that no-fault states actually have lower premium rates. And Snyder Herrin, executive director of ITLA pointed out that premium rates in Massachusetts have apparently been rising since their dramatic decline and are now again in the same range as before the no-fault period. But given the current rate of inflation, the rise back to 1971 figures may mark an actual reduction in relative premium rates.

Unknown risks

Most insurance companies prefer the no-fault system because it provides more information on their risks, since they would be reimbursing their own insurance holders. Under the liability system, insurance companiesend up paying to virtually unknown risks who are eligible for reimbursement simply because of the outcome of a lawsuit. In the case of wage loss benefits under no-fault, an insurance company can adjust its premium rates to the known income of its policyholders. A person with moderate earnings would thus pay an appropriately moderate premium rate for wage loss coverage, the insurance spokesman pointed out.

As to no-fault's effect on reducing court congestion, Herrin argued that it was not an issue at all since the vast majority of suits filed in court are criminal rather than civil, and contested insurance settlements are not the cause of court congestion. Herrin also said the reduction of large settlements by jury verdicts as a result of no-fault has a negative effect on reinforcing traffic safety. "Under no-fault, your company is going to pay for you even though you were to blame" for an accident, he said, in comparison to the supposedly accident deterring influence of liability insurance.

A 1973 publication by the Pennsylvania Department of Insurance points out that liability insurance was originally conceived as a deterrent to careles: driving. However, according to a number of polls, the public did not agree this was the case, the publication says. The same publication also indicates the stake lawyers have in the liability system: "In 220,000 lawsuits studied bj the U.S. Department of Transportation, accident victims collected $1.4 billion in compensation for their accident loss. Of this amount, attorneys collected $600 million in fees and $100 million in expenses, leaving $700 million -- or exactly 50 percent -- as direct benefit to the victims." And O'Connell has pointed out that in 1971 in Chicago, 75 percent of all automobile accidents were settled with the assistance of attorneys.

An awareness of the potential abuses in the liability system has apparently touched the consciousness of the public in recent years, according to a national survey of drivers conducted by the Kemper Insurance Company in 1977. Despite the efforts of the lawyers' groups and their concern for the cherished right of citizens to have access to legal resolutions, 79.8 percent of those surveyed in the Kemper study indicated that liability insurance was not the most desirable option.

Prevailing forces

But nationwide, as in Illinois, the anti-no-fault forces still prevail, and only 16 states have adopted pure or even threshold versions of the law. (Massachusetts in 1971; Florida in 1972; Connecticut, Michigan and New Jersey in 1973; Colorado, Hawaii, Kansas, New York, Nevada and Utah in 1974; Georgia, Kentucky, Minnesota and Pennsylvania in 1975; and North Dakota in 1976.) Eight other states, among them Oregon, have phony no-fault insurance provisions, allowing accident victims unlimited rights to sue.

And at the federal level, as in Illinois, the tug-of-war continues. Eleven years after the no-fault notion was first debated in Congressional hearings, no-fault bills have come and gone and returned. Even the added weight of Jimmy Carter on the no-fault side has so far failed to budge the powerful forces arrayed on the side of the status quo.

Martha Collins is a graduate of the Public Affairs Reporting Program at Sangamon State University. She interned with the Alton Telegraph at the Stalehouse.

August 1979 / Illinois Issues / 15

|

|