|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By BEVERLY ANN FLEMING and JOHN N. COLLINS The American housing dream: a report Despite huge initial costs, the difficulty of obtaining a mortgage and the strain on family income, more and more Americans are buying their dream house. How? When will first home buyers have to settle for less? What are the alternatives? [This article is the first in a series on Illinois housing problems. The series is supported by a generous grant from the Ford Foundation made to Illinois Issues and the Center for Policy Studies and Program Evaluation, Sangamon State University. Future articles will cover the major aspects of Illinois housing and will be collected into a booklet. — Editor.] BUY A HOUSE. One with a big yard if possible. Fix it up, improve the real estate. Plant some trees and a garden; raise a family. Call it home. This is the American Dream, or a central part of it anyway. Of late, this dream has become more remote for many young couples. According to a 1978 survey of Illinois households conducted by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, one of the most serious issues in Illinois is the lack of single-family houses people can afford to buy. The skyrocketing costs of homeownership have produced a spate of books, commission studies and media reports on the steadily worsening situation, the potential default of the American housing dream. In the past, a majority of our population were able to realize the dream of homeownership. For example, approximately 60 percent of all residential units in Illinois are owner-occupied. But in the future, housing experts question whether homeownership will continue to dominate the housing market. Both for reasons of affordability and changes in household need and demand, Americans may be forced to give up the dream of owning a single-family house and settle for something less — or something different. The postwar baby boom generation is coming of age, and by 1985 there will be 30 percent more Illinois residents in the prime home-buying age group of 25 to 44 than there were in 1975. As first-time home buyers, this group will be hit the hardest by the rising costs of homeownership. Without equity from previous ownership, they will be hard pressed to come up with the down payment needed to buy into the housing market. Most of this group has been raised with the middle-class expectation that they should and will own homes by the time they are ready to start a family. The tradition Homeownership has a long tradition. Many of our ancestors came to America specifically to gain economic independence through land ownership, In Europe, land was characteristically held by a small ruling class, a circumstance that rankled the burgeoning and ambitious middle class. In the new country the family would live off the land which would guarantee economic independence. By the end of the 19th century, however, land ownership was becoming less and less essential to earning a livelihood. Nonetheless, 16/January 1980/Illinois Issues homeownership still provided economic security as well as shelter. It still does. A 1977 U. S. League of Savings Associations' survey of mortgage borrowers determined that homes account for over 50 percent of the total assets of all homebuyers. Lengthy foreclosure procedures that benefit the property owner insure that in times of unemployment or sickness the family that owns its home will still retain its shelter. Homeownership is a form of mandatory savings, an investment which offers what has proven to be the most reliable hedge against inflation. Appreciation of home prices have consistently out-performed all stock and bond averages over the last 10 years. Although Americans readily acknowledge the economic benefits of homeownership, they are almost reverent in their attitude toward the social benefits of homeonwership. In a 1975 nationwide Roper poll, 85 percent of those interviewed considered homeownership to be an integral part of the good life. Where we live is an indication of our social status. A single-family detached house is regarded by the American public as the proper place to raise a family. Tenancy is considered a suitable temporary housing solution for certain types of households — singles, elderly, newly-weds, but it is not considered to be the environment children need. Homeownership is thought to generate values such as dignity, pride, responsibility and stability in the property owner. Political participation at the local level, is higher among homeowners than among renters. In contrast, tenancy connotes mobility, instability, dependence and lack of responsibility. The homeowner is believed to be a superior citizen — one who cares about community and civic affairs. The future value of a home investment is dependent upon the community and neighborhood remaining a "good place to live." Homeownership is also believed to be conducive to the general improvement of a community's housing stock. It is argued that homeowners are more careful in upkeep and maintenance than the joint effort of landlords and tenants. America believes that homeownership is good for the family and for the country; it has been strongly supported by government housing policy.

Coupled with such sentiments, however, is an economic argument which further explains government support for homeownership. Continuing population growth and the frontier mentality of replacing the old with the new has necessarily supported the construction of new homes. The construction industry is our second largest industry and its strong lobby has been in the forefront of support for governmental programs which promote homeownership. In the past, this lobby strongly supported the Federal Housing Administration program. It was also the strongest voice against the 1949 Housing Act, which relied on public housing, not homeownership, as the solution to America's housing needs. The landmark Housing and Community Development Act of 1968 stressed homeownership for low-income families as a major goal and mandated the subsidized single-family construction program (section 235). Since the early 1970's, however, government has backed off from its goal of homeownership for all Americans (regardless of income), and has increased its support for low-income rental January 1980/Illinois Issues/17

housing subsidized by public funds. In Illinois, the Illinois Housing Development Authority promotes such housing through its program of below-market-rate mortgages and construction loans to nonprofit and limited dividend developers of low- and moderate-income rental housing. For middle-income families, however, both federal and state policies continue to support homeownership through tax deductions, government insured mortgages, low-interest mortgages through use of public bonds, and property tax relief measures. The costs The cost of homeownership is rising. A study by the Chicago Title Insurance Company has determined that in 1968 the average household spent 29 percent of its disposable income to buy and maintain a new home. In 1978, this figure had increased to 40 percent. To purchase and maintain an existing home, 28 percent of a household's disposable income was required in 1968; in 1978 it was 37 percent. The rise is due to increasing costs for new construction, home finance and maintenance. Two other factors are the number of people demanding homeownership, which drives up prices, and America's high expectations with regard to living standards. Yet, despite these factors, a 1977 U. S, League of Savings Associations' study concludes that the number of homeowners is increasing. This conclusion is confirmed by U. S. Bureau of Census data for 1950 to 1976: homeownership for every type of household has increased or remained the same during this period. In Illinois, the savings and loans institutions, principle suppliers of home financing, made $7 billion in loans in 1978, an increase of 4.3 percent from 1977. More and more Americans are buying into the dream. How? According to the Chicago Title Insurance study, despite increasing costs, the proportion of disposable income spent on housing drops with the length of ownership. For the average household that purchased a new home in 1968, the percent of disposable income spent on housing declined from 29 to 24 percent by 1978. For an existing home purchased in 1968, housing expenses declined 6 percent to 22 percent during the 1968-78 period. Thus, it is the huge initial cost of homeownership, not to mention the difficulty of getting a mortgage loan that is threatening to price the average family out of the market. First buyers, who do not have the equity or appreciation from a previous home to apply towards a down payment, comprise 36 percent of all home buyers. The most common strategy among this group is to purchase an inexpensive home, and then "trade up" to a more expensive one. The media frequently compares the average price of a new home in 1979 ($70,000) to the average price of a new home in 1970 ($23,000) to indicate the financial straits in which young families find themselves. But any average price comparisons must consider differences in the product. The average new house in 1978 was likely to contain more amenities and be larger than the new house of the past. In fact, all of our housing has risen in quality. In 1950, about one third or 34 percent of all households nationwide lived in substandard housing; this proportion has now shrunk to less than 5 percent.

I8/January 1980/Illinois Issues

As Terry Paul, executive director of the Illinois Home Builders' Association pointed out in a recent interview, "The family of today shopping for a new home wants more in a house than they wanted 10, 20 or 30 years ago. A house is a reflection of how well I've done." At the end of World War II the average size of a house was just under 1,000 square feet; in 1978, the average size was 1,700 square feet. Fireplaces, central air conditioning, garbage disposals, and dishwashers are standard features rather than luxuries in new houses. Current new construction is being produced for buyers at the upper end of the homeownership market. Unlike the 50's and 60's, very little low- or moderate-income new housing is being built. Builders say there is no demand for such housing. This is illustrated by the lack of enthusiasm for the "no-frills" house, an effort of the building industry in the early 1970's to offer a basic house with no extras and a moderate price tag. It did not sell. Nor is there much motivation for a builder to construct moderately priced houses, when more profit can be made by building expensive houses. It is misleading to compare new housing prices today with new house prices in 1970 and 1971 when the federal government was heavily involved in the subsidy of single-family construction. The average price of a new house in 1977 was about $55,000, yet 62 percent of all home buyers purchased homes costing $50,000 or less. The average American family may be priced out of the new home, but this does not mean they cannot buy an older one. It is unclear whether all Americans should be able to buy a new home. Of course, the increase in the cost of new construction is reflected in the resale prices of older homes and rental units as well. Housing markets are subject to widely varying local conditions, so average or median home prices can be misleading. The housing market of highly populated urban areas is much different from that of smaller communities. According to the Savings Associations' survey, within Illinois, the 1977 median purchase price of a house in Chicago was $50,900 (median down payment, $11,600), while in the Peoria housing market the median purchase price was $36,000 (median down payment, $4,753). The average American family in Chicago may well have more difficulty buying a house, (but incomes are higher too) than families in the rest of the state. The difference between housing markets can mean a large profit or a large loss to households who move from one market to another. The new home represents the upper end of the homeownership sale today, and the mobile/manufactured home represents the lower end. More than 76 percent of all homes under $30,000 sold in 1978 were mobile/manufactured homes. Although mobile/ manufactured homes are not financed through regular home mortgage channels, they represent a significant proportion of the homeownership market. With the relaxing of zoning regulations, the improvement of mobile home park landlord/tenant laws, easier financing, less unit-depreciation, and the creation of the mobile home subdivision, the mobile/manufactured home has become increasingly attractive. Americans can afford more expensive homes because they have been willing to pay a greater percentage of their income for them. The 25 percent norm is regularly exceeded. This has been a particularly common tactic among low- and middle-class households and first-time buyers. They know that their fixed mortgage payments will become easier to pay as their income increases and so are willing to exceed the 25 Janaury 1980/Illinois Issues/19

percent guideline in order to get into a house. There is a limit, of course, to how much sacrifice a family can make to increase the number of dollars available for housing. The widespread use of consumer credit in the past decade has bridged the gap between inflation, the family's rising expenditures, and income levels that have not kept pace. But consumer credit has also reached a point of limited further expansion. The American family has been using two incomes, rather than one to pat-chase a home. Half of all married women are working, creating a sharp split in the housing market between families with two incomes and those with only one. The Savings Association survey found that 45 percent of all buying families have more than one wage earner. Thirty percent of all secondary earners contribute between 30 to 50 percent of the total household income. Without two paychecks, homeownership would not be possible for many families. Warren Purcell, executive director of the Illinois Savings and Loan League, believes that the demand for homeownership has stayed high because of inflation. The consumer does not believe that either housing or interest rates will go down and so concludes it is better to buy now, regardless of price. This rush to buy sooner than later has placed further pressure on the market already heated by baby boom demand. Individuals and childless couples are also getting into the single-family housing market much earlier in their lives than they would have in the past, often purchasing housing space far beyond their physical needs. Of all 1977 home buyers in the U. S., 17 percent were single, drawn to homeownership not by space needs, but by the investment advantage. With no children, singles and childless couples have more dollars to spend on housing. They can afford homeownership, especially if they are part of the increasingly affluent young professional class.

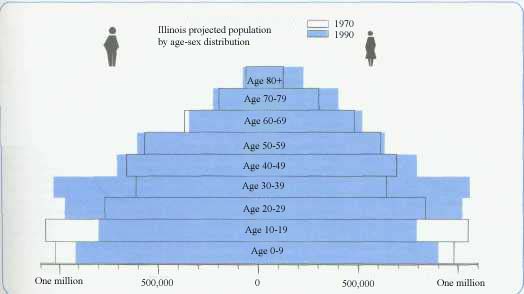

The Illinois Bureau of the Budget has identified several state demographic and social economic trends, (most of which are paralleled nationwide) that are likely to continue through the next decade. These trends suggest that future housing demand within the state may differ from the housing demand of today. If so, the price of a single-family home may be irrelevant for a significant number of Illinoisans. It is possible that the traditional American deam of homeownership may not suit households of the future. Household demand The number of households in Illinois is projected to increase by 30 percent from 1970 to 1990. However, the size and composition of these new households will be different. Past demand for the single-family home was based on an average household size of four (father, mother and two children). Average household size in the U. S. is; projected to drop from 3.14 persons in 1970 to 2.55 by 1990. In Illinois, average household size is projected to drop from 2.96 persons in 1970 to 2.47 persons by 1990. For all age groups, Illinois has a larger percent of single persons and of individual households than does the total U. S. population, thus lowering Illinois' average household size in comparison to the U. S. as a whole. In 1970, husband/wife households accounted for 68.7 percent of Illinois total households; the remainder of Illinois' households were divided between other male head families (2.3%), female head families (8.5%), primary male households (7.8%), and primary female households (12.8%). If present trends continue in Illinois, husband/wife households are projected, to grow only 26.8 percent between 1970 and 1990, while other male head families are projected to grow 44.7 percent, and female head families are projected to grow 64.8 percent 20/January 1980/Illinois Issues during the same time period. Males living alone are projected to increase 129.8 percent between 1970 and 1990 while females living alone are projected to increase 81.9 percent. The growth of households other than the husband/ wife family is the result of several trends of the 60's and 70's: the postponement of marriage in pursuit of careers and advanced education; the decision of couples to live together rather than marry; a rise in the number of illegitimate births; high rates of divorce; the disappearance of the extended family; and the increase in the proportion of our elderly population. These households will create a different housing demand than in the past. In 1975, the number of people in Illinois age 65 or over was 1.15 million, or approximately 10.3 percent of the state's population. As advances in medicine continue to lengthen life expectancy rates, Illinois' elderly population is projected to rise to 1.4 million by 1990, or 11.6 percent of the state's projected population. Due to a variety of physical ailments and limited incomes, the elderly often need housing designed and located for their safety and comfort. For example: no stairs, grab bars in the bathroom, easy maintenance, convenient access to community facilities, recreation and supportive services. The traditional single-family home is often ill-suited to meet the financial and physical needs of the elderly, unless provision is made for support services (i.e., special transportation, meals-on-wheels and tax relief). In addition, approximately 8 percent of the state's present population is disabled, a group which also has special housing needs. It has been estimated that 40 percent of the children born in the 1970's will spend part of their childhood in a single-parent household, the majority of which will be families headed by females. As the income level of a female-headed family is generally half that of a husband-wife family, this household type needs low- or moderate-priced housing that is suitable for children. Homeownership of a single-family house may be highly desirable for this group of households but it is financially impractical under present market conditions. The single or childless household will create a demand for housing located near adult pursuits: work, entertainment, recreation, and cultural activities with less emphasis on access to good schools and other child-centered activities. These two types of households are likely candidates for inner-city living. Ownership opportunities other than the single-family, detached house; for example, the townhouse, condominium or cooperative, could better satisfy their physical and social housing needs and still provide an investment advantage over tenancy. Geographical demand Due to the local nature of housing markets, determining Illinois' future housing need is not simply a matter of projecting the number and type of Illinois' future households. Often a housing shortage is not due to a lack of actual dwelling units, but results from the fact that dwelling units are not geographically located where the state's population wants to live. Three possible migration trends within the next decade may affect the geographical demand for Illinois' housing units. Nationally, the exodus following WWII from the rural south to the northern industrialized cities has virtually ceased. At present, the nation's population, especially the elderly population, is moving to the sunbelt states. Illinois' population can be expected to continue to increase in the future, as it is now, at a slower growth rate than the nation as a whole. It is unlikely that Illinois will suffer the housing shortages that may occur in the rapidly expanding West and South. Within the state, Illinois' rural population has stabilized, suggesting a potential revival of rural housing. Stabilizing factors are the return to small towns of urban families seeking a quieter life and the (possible) re-vitalization of the coal industry in southern Illinois. Some demographic experts believe that it is not possible for the farm population, regardless of further mechanization, to decline further and still maintain the present numbers of acres in agricultural production. Since the 1950's, America's love affair with homeownership has centered upon the new house on a large lot in suburbia. This has led to the deterioration of our cities. If the energy crisis deepens, geographical location will become critical when households make housing choices. Central city revitalization may occur and suburban living may lose its present popularity. The homeownership dream is a central tenet of American life — a dream heavily supported by government housing policy. The rising cost of homeownership has led some observers of the housing market to argue that the average American family will be priced out of homeownership in the next decade. It is more likely, however, that one or both of two things will happen: either middle-class dissatisfaction with the high costs of homeownership will force government to increase homeownership opportunities; or, Americans will voluntarily modify their homeownership dreams. The dream does not belong merely to a small, impoverished minority; it is the dream of middle America, a large voting bloc whose demands will be difficult to ignore. How federal, state or local government should act to increase homeownership opportunities is open to question. In light of housing's close and critical relationship with the national economy, the answers will be difficult. Three courses of action that have been proposed are: the elimination of excessive government regulation of the construction industry, new mortgage instruments, and the development of a residential rehabilitation industry. (These and other alternatives will be discussed in future articles). The present homeownership dream is based on the "good life" in suburbia. It is not certain that this will remain the definition in the future. The demand for the single-family detached house has been based on the traditional husband/wife household, and while this type of household will continue to exist, new types of households may not need nor want a single-family detached house. Instead, they may be interested in ownership opportunities such as the condominium, cooperative or town house. It is quite possible that Americans will dream a new version of the American housing dream. Beverly Ann Fleming holds a master's degree in urban planning from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is a research associate at SSU's Center for Policy Studies and Program Evaluation, which is directed by her co-author, John N. Collins. January 1980/Illinois Issues/21 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|