|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Daley's victory — a prelude to the big brawl

Sen. Richard M. Daley narrowly defeated incumbent Bernard Carey in the race for Cook County state's attorney. Carey ran on his record but was shunted aside when Mayor Jane Byrne became the issue, and the race became a brawl. An extraordinary contest even by Cook County standards, it was just one more episode in the larger struggle to decide, amid shifting alliances, the fate of the Chicago machine. THE RAZOR SHARP race for Cook County state's attorney between the Republican incumbent Bernard Carey and his Democratic challenger state Sen. Richard M. Daley is but the latest example of how Chicago Mayor Jane "Byrne and "her press agent "husband, Jay McMullen, have reshaped and restructured Chicago and Cook County politics. The pair's political activities, press statements and media pronouncements changed the entire rhythm of the campaign, and by their actions, they and not the candidates became the central issue. Following Daley's landslide March primary victory over 14th Ward Alderman Edward Burke, Mayor Byrne's candidate, most of Cook County expected a traditional party battle for the state's attorney office. In 1976 Carey had won a narrow victory over Judge Edward Egan by piecing together a coalition of Republican suburbanites and independent-minded city voters. His 1980 Democratic challenger was heir to the grandest name in Chicago politics and thus, the race had the earmarks of a classic city v. suburban struggle. At first, campaign events followed customary and familiar political pat-terns. In June, Carey received the overwhelming endorsement of the Independent Voters of Illinois-Independent Precinct Organization — a liberal organization which had backed him in his two previous successful state's attorney races. Daley countered with a string of endorsements from independent black and white state legislators and city aldermen. And though some eyebrows were raised at Daley's efforts to attract liberals and independents like 43rd Ward Alderman Martin Oberman and 13th District state Sen. Dawn Clark Netsch, nothing extraordinary had yet occurred in the state's attorney race. Presidential politics and the national political conventions made the summer a time for both candidates to organize their fall campaigns. To manage his campaign, Carey picked Don Rose, a long-time foe of the Democratic machine and Byrne's chief strategist in her February 1979 primary upset of former Mayor Michael Bilandic. Rose devised a strong media campaign whereby Carey would run on his record and his qualifications and against the Chicago Democractic organization. On the other hand, Daley's brother William headed a campaign organization which was a combination of family members, old friends of the /ate mayor and a surprising number of independent Democrats. To further attract independent voters, Daley unveiled an impressive blue ribbon panel of advisers who he claimed "would establish guidelines, standards and programs for his office if he was elected Cook County state's attorney." Unlike Carey, Daley's campaign would stress traditional ward and township organization politics, and in many ways it would be a throwback to the rally and meeting type campaigns of his father. 4/January 1981/Illinois Issues

Post-primary prelude Byrne and McMullen were spectators during the early Carey-Daley maneuvering. Following the primary, the mayor had endorsed the entire county Democratic ticket, including Daley. She also took a vow of political abstinence, and despite a brief and somewhat clumsy political appearance at the Democratic National Convention to aid Sen. Edward Kennedy's last ditch nomination efforts against Carter, she remained true to her word — until mid-September. The attacks against Richie Daley started over a Daley fund-raising dinner featuring Rosalyn Carter. The mayor was angered that she and some other Democratic ward committeemen like John D'Arco (1st), Edward Vrdolyak (10th) and Edward Quigley (27th) had not been invited. Moreover, she claimed Daley was running a campaign of "hate" against her and her political allies because he believed that McMullen had leaked to the news media stories about Daley's involvement with the controversial estate of the late Fire Commissioner Robert Quinn. She also chastised Daley for his association with Earl Bush, Mayor Daley's former press secretary who was convicted in federal court for influence peddling, and she said 23rd Ward Alderman William Lipinski was helping Daley only because Lipinski was angry at her because she torpedoed his candidacy for county recorder of deeds. In typical Jane Byrne fashion, she scattergunned her accusations and opinions, and yet she maintained she still supported Daley because she was a good Democrat — though she wished Daley would come to his senses. Richard Ciccone, Chicago Tribune political editor, believed Daley's fund raiser snubbing of Byrne and her associates was a calculated political move. "It reflects," wrote Ciccone, "the thinking in the Daley camp that the best way to win independent and liberal votes he needs to beat Carey is to identify himself as an enemy of the mayor." Whether planned or not, Daley baited the mayor and she swallowed the entire hook. William Daley phrased his comment on Byrne's outburst in Uncle Remus fashion: "Mayor Byrne had stated that she is going to stay out of the state's attorney race . . . apparently she has changed her mind." Following the September outburst, the Byrne-Daley feud simmered for several weeks. In early October, however, the entire drama erupted into front-page political headlines pushing the presidential election aside. Daley charged that Byrne was telling key Democratic ward committeemen to minimize their efforts on behalf of his candidacy. Words like "trim," "knife" and "shave" were reintroduced into Chicago's political vocabulary as pundits talked about the methods that pro-Byrne committeemen could use to slice Daley's vote in their wards. If Daley wanted this latest salvo to engender a response from City Hall, he was not disappointed, but even he must have been a little surprised at the intensity of the retaliation. Immediately, McMullen denied the accusations calling Daley "sick and paranoid" and suggested he ought to see a psychiatrist. "I don't know what's going on in his mind," said McMullen, "but there is a nest of wooly caterpillars in there somewhere." The gloves were now off and with the local media playing the role of messenger, the state was set for a political brawl, Cook County style.

The press reported that three pro-Byrne black Democratic ward committeemen were considering endorsing Carey. One committeeman, Alderman Tyrone McFolling (17th), claimed that he was furious at Daley for opening up a campaign office in his ward without permission or consultation. Near south side white Alderman Aloysius Majerczyk (12th) charged that he had been slighted by Daley following the primary, and he too was leaning towards Carey. The bizarre appeared commonplace, and even the Chicago Tribune in an editorial entitled "On Campaigns and Caterpillars" fell prey to the enfolding melodrama. According to the Tribune, "When a political leader sees a fellow party member as a threat, that leader is not bound by law to help him become a stronger one." Issues in the actual campaign for state's attorney received short shrift. No one appeared to listen as Carey stressed his qualifications, record and integrity, and even Rose's clever political commercials created few political waves. Daley talked about toughening laws against rape and drug selling, but few heeded or even concentrated on his message. Most were waiting for the next bombshell in the Byrne-Daley war — and the mayor did not let them down. First Bismarck rally In late October, Byrne skipped the first of two traditional Democratic precinct captain rallies at the Bismarck Hotel. Daley did attend, but his speech was marred by the open defiance of several Democratic ward committeemen who admitted with surprising candor their coolness to his candidacy. The next day Byrne ended any charade of Democratic unity by withdrawing her endorsement of Daley. At a hastily called news conference, the mayor claimed that a local television station had discovered and was about to divulge a pattern of racial discrimination in Daley's llth Ward Bridgeport area. According to Byrne, she "could not in good conscience support Daley because ... he condoned the use of city inspection powers to discourage racial minorities from living in his llth Ward." The next few days were strange even for this extraordinary campaign. Byrne, showing full faith in the veracity of the TV station's investigation, produced three present and past building department employees who gave examples of the power of the llth Ward in building and zoning matters. January 1981/Illinois Issues/5 However, none of the witnesses gave any specific instance of discrimination against minority group members or in any way implicated Daley in the matter. Byrne and McMullen kept promising more evidence but none came. Finally, on October 29th, the Chicago Sun-Times summed up the episode by arguing that Byrne was unable to furnish any "smoking gun" to back her accusations and that the charges made against Daley lacked any real evidence. Byrne's racism charges against Daley, whether true or false, had the political potential to scuttle his campaign. Daley needed a large black vote from the city to hold off the expected Carey landslide in the suburbs. In the past two state's attorney races, Chicago blacks had played prominent roles in stopping Democrat Edward Hanrahan's 1972 reelection bid and in almost electing Democratic challenger Edward Egan four years later. In 1972, black voters, especially in the heavy voting, middle-class south side wards, split their tickets in such numbers against Hanrahan that not one normally heavy Democratic black ward placed in his top 10 plurality wards. In 1976, these same black voters reversed themselves by giving Egan strong support, and seven black wards placed in his best 10 list. Whether planned or unplanned, Byrne had hit Daley where it could hurt the most — the black vote.

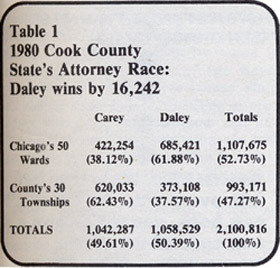

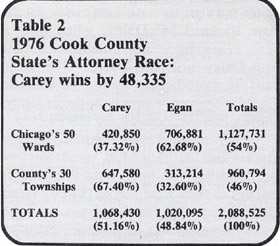

One week prior to election day, Democrat Daley was facing Democrat Byrne in an all-out political offensive directed against him. If his strategy was to make Jane Byrne the central issue in the campaign, he had succeeded, but the potential price was large-scale defections from his candidacy by several key Democratic ward committeemen and possibly the fatal erosion of support in the black community. Daley struck back out of necessity and anger October 28 at the second Bismarck Hotel precinct captain rally. His speech before the party faithful was without precedent in Chicago's political history. Daley tore into the mayor calling her ruthless and malicious and accused her of following a policy of ruling by fear which he said "will not end until it is checked." He charged her of being in collusion with Carey to defeat his candidacy and of engaging "in a hit-and-run campaign full of innuendos, smears and false charges." He compared her to the late Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy and claimed like McCarthy, she was using the technique of the big lie in her racial discrimination charges against him and his llth Ward. Finally, Daley told the stunned audience: "There isn't a precinct captain, a Democratic worker, a businessman, or a professional who does business with the city who does not fear Mayor Byrne . . . [and] everyone in this room knows it." Four generations ago Finley Peter Dunne's fictional bartender, Mr. Dooley, said that "Chicago politics was not bean bag." However, even Mr. Dooley would have beem impressed by the ferocity of the Daley-Byrne battle — it had, in fact, turned into a bare knuckles barroom fight. Daley needed allies and in a campaign filled with twists, double crosses, and strange alliances, it was still mind-boggling when suddenly Sun-Times newspaper columnist Mike Royko, the long-time Daley family critic (whose book Boss the late mayor's wife tried to have removed from her neighborhood supermarket bookshelves), started blasting away at Carey. He belittled the state's attorney's conviction record, he made light of Carey's much trumpeted award as the nation's best prosecutor, and he sniped at Carey for ducking politically sensitive cases. Royko at his sarcastic best ran off the list of political forces working against Daley and called the challenger "the most under of any underdog I've seen run for office in Chicago." Royko's biggest bombshell was dropped on Sunday before the election when he raked Carey's office for not being more aggressive in prosecuting mass murderer John Wayne Gacy. Royko claimed an assistant state's attorney in Carey's office refused to file charges against Gacy a year before Gacy was charged with the murders of 33 young men and boys. Carey now was completely on the defensive. He lashed back at Royko calling his Gacy column an "llth hour smear." Carey labeled Byrne's racism charges against Daley as unfair. Endorsed by almost every newspaper, radio and TV station in Cook County, considered the darling of anti-machine independents for almost a decade, and a man proud of his reputation for running a nonpolitical state's attorney's office, Carey had to spend the last week of the campaign trying to separate himself from Mayor Byrne and her Democratic ward committeemen. Election eve defense Carey, in language similar to that used by Daley's March primary opponent Alderman Edward Burke, told county voters on election eve to forget Byrne in the state's attorney race. He summed up his political predicament by stating: "... Daley has portrayed himself as a martyr or a victim, when in fact, I have been the victim because it has caused the voters to overlook the relative qualifications of both candidates. I have stood outside the battle and got the fallout. It's like standing too close to Mount St. Helens. Everytime it erupts I get covered with ashes." As dawn broke on November 5, the results of the 1980 Cook County state's attorney contest found Daley narrowly defeating Carey in one of the closest races in county history. Daley's winning plurality was slightly over 16,000 votes and his winning percentage was slim 50.39 percent. A comparison of the 1976 and 1980 state's attorney returns reveals that Mayor Byrne was unable to sink Daley's candidacy in Chicago. In fact, for almost every vote she helped trim in one part of the city, another voter switched to Daley elsewhere in Chicago. Thus, Carey gained only 1,404 votes over his 1976 city totals while Daley's Chicago totals were down by 21,460 votes from Egan's 1976 tally — a net percentage gain for the Republican of less than 1 percent. In suburban Cook County, the 1980 percentage shift was far more dramatic than in the city. Daley received almost 60,000 more votes than Egan in the 30 suburban townships while Carey's suburban vote totals dropped by over 27,500 votes. This remarkable shift gave Daley almost a 5 percent net gain over the suburban spread Carey enjoyed over Egan four years earlier. This suburban boost for Daley takes on even more significance when one considers that the suburban percentage of the total vote for state's attorney increased by over 1 percent due to a 32,377 suburban vote gain coupled with a 20,005 city vote decrease. All in all, in comparing this race with 1976, Daley managed a 64,577 vote turnaround with all of his increased margins coming from the suburbs. A detailed analysis of the Chicago vote shows that Carey carried 10 wards — one less than he won in 1976. As in 1976, the north side, lakefront liberal wards were Carey's strongest areas with the 43rd Ward producing by far his largest margin of victory — 8,805 votes. The only south side ward Carey won was the liberal, Hyde Park 5th Ward, but the totals here reveal Daley's inroads with the University of Chicago crowd — Daley lost the ward by only 95 votes.

Daley's strongest areas in the city were the ethnic southwest side white wards and some black middle-class south side wards. However, no ward in the city produced like Daley's home llth Ward. Bridgeport residents, famed for their support of the Daleys and angered over Byrne's attacks, backed their native son with a massive voter turnout. Daley received over 91 percent of the llth Ward's vote; his vote margin in the ward was an astounding 21,960 votes; and as in the March primary, Daley's llth Ward margin was larger than the combined vote margin for all the city wards won by his opponent (over 3,600 votes greater). The black wards Byrne's efforts to knife Daley hurt him in the black community and in a few selected north side white wards. A ward by ward comparative analysis of the 1976 and 1980 state's attorney city vote margins reveals that 28 Chicago wards gave Daley less support than they gave Egan. The "cut" champion was Tyrone McFolling's 17th Ward (down 9,424), while three other south side black wards — 34 (Wilson Frost), 9 (Niles Sherman) and 16 (James Taylor) — were in the top five. The other ward high on the cut list was John D'Arco's 1st Ward where the committeeman shaved almost 8,000 votes from his 1976 Democratic state's attorney column. Interestingly, an examination of the lakefront and independent-minded wards discloses that Daley was cut only a combined 700 votes, and this was accomplished only by strong efforts by Byrne operatives in the 49th and 46th wards.

Daley increased his margins over Egan's totals in 22 wards. Though these wards were scattered throughout the city, the heaviest increases occurred in the southwest side ethnic wards. Lipinski's 23rd Ward led the way with a 7,980 vote increase. The four other of the top five wards to increase the vote were Michael Madigan's (13th), Theodore Swinarski's (12th), Tom Hynes' (19th) and Daley's own llth. In sum, the city returns reveal that vote margin decreases for Daley in most black wards were nearly offset by increases for Daley in mainly southwest side white wards. Outside the city, Daley made a remarkable showing compared to Egan's 1976 performance. Daley won two small south suburban townships, Calumet and Stickney; came close to carrying another one, Lemont; and he bettered Egan's vote margin differential against Carey in every township except Harrington. As Egan in 1976, Daley ran poorest in the heavily populated north suburban townships. For example, his worst plurality township was Wheeling where Carey defeated Daley by over 25,000 votes (which was still 3,000 votes less than 1976). Daley's most impressive suburban gains were in those southwestern and western townships bordering the city wards. These townships voted like extensions of their city neighbors in cutting down Carey's vote margins. Worth Township just south of the city was the scene of Daley's most electrifying suburban vote margin jump. In 1976, Carey beat Egan in Worth Township by over 18,000 votes; Egan received less than 37 percent of the township vote, and plurality-wise, Worth was listed as Egan's 5th worst defeat in suburban Cook County. In 1980, Daley lost Worth by less than 5,000 votes; his percentage of the vote increased almost 10 percent, and percentage-wise, Worth ranked as Daley's 4th best township. To a lesser degree the Worth example was replayed in every other township except Harrington. Proviso Township west of the city increased Daley's vote over Egan by 7 percent while trimming Carey's victory margin by 10,000 votes. Leyden and Cicero townships also west of the city reduced Carey's winning 1976 margins by over 6,000 votes. Generally, in the suburbs, it appears Daley did better than Egan did in townships having large ethnic, blue collar, Catholic populations and Daley did only a little better than Egan in those townships which have heavier Protestant and Jewish white collar voters. January 1981/Illinois Issues/7 Following the election several Carey supporters gave their opinions on why their candidate lost. Cook County Republican party chairman J. Robert Barr laid the blame on Carey's failure to pay attention to the Republican party structure. "I can't imagine," said Barr, "a Democratic county official seldom talking to the county chairman of the party or staying away from official slatemaking meetings." Gov. James R. Thompson disagreed with Barr's analysis that Carey lost touch with party leaders. The governor said, "He lost because it's tough to beat Royko, Bryne and Daley all at once. . . ." Don Rose, Carey's campaign manager, also disputed Barr's analysis. Rose said that "Carey didn't do as well in the suburbs as he did in 1976 because the percentage of Democratic voters is rising in the suburbs." It is Gov. Thompson who has hit the bull's-eye in explaining Carey's defeat, even though Thompson leaves the mayor's press secretary out of his analysis. It appears that Jane Byrne and Jay McMullen beat Bernard Carey. Barr is off base in chastising Carey for not being a party man; being nonpoliti-cal was Carey's great appeal to the county's ever-growing number of independent voters. Rose's assertion that Democrats are increasing percentagewise in the suburbs is correct, but in itself it does not explain Carey's 5 percent suburban drop-off. Suburban Democrats are not a homogeneous bloc of voters. They do not have the same political philosophy, nor do they place much reliance on party loyalty. A good chunk of the new suburban Democratic vote is made up of independent-minded voters who have traditionally supported Carey.

Jane Byrne gave Daley an issue — herself. The mayor's full involvement in the campaign foreclosed any real discussion of the state's attorney's office. Instead, the campaign became a referendum on her popularity, the direction of the city of Chicago, and the future political fortunes of Richard M. Daley. Without Byrne, Carey's overwhelming number of endorsements, his scandal-free two terms in office, and his lack of any political enemies would have insured another victory for him. However, the mayor's injection of controversial personal and racial issues into the campaign so flip-flopped traditional voting patterns that after the smoke had cleared Carey was simply outcounted. In an Illinois Issues article, "The Irish Game: Watch Byrne Watch Daley Watching Byrne" (September 1980), my colleague Peter W. Colby and I said of the upcoming Carey-Daley contest, "Byrne's opposition to Daley . . . [has] made Daley more acceptable to Carey's bedrock support — peripheral ward Chicagoans and the suburbanites. It is ironic that anti-machine votes may go to state's attorney candidate Richard M. Daley, when only a few years ago, anti-machine meant anti-Daley not anti-Byrne." In large part, our prediction came true because Daley received enough support from these voters to squeak by Carey. What about the future? Mayor Byrne and her husband must already be planning for upcoming party skirmishes as they gaze across the city from their Chestnut Street high-rise. And the 1983 Democratic mayoral primary looms big on the horizon. In 1983, the two Chestnut Street cyclones will face a direct challenge from either State's Atty. Daley or one of his allies. The victor in that election will control the destiny of the city and future of the local Democratic party. And though it is too early to predict a winner, one thing seems certain: that election will spell life or death for the 50-year-old Democratic machine. Paul Michael Green is chairman, division of public administration, and director, Institute for Public Policy and Administration, Governors State University, Park Forest South. The author acknowledges the research assistance of GSU graduate assistants Mary Jane Blustein, Kathy Cardona and Marty Libles. January 1981/Illinois Issues/8 |

|

|