|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

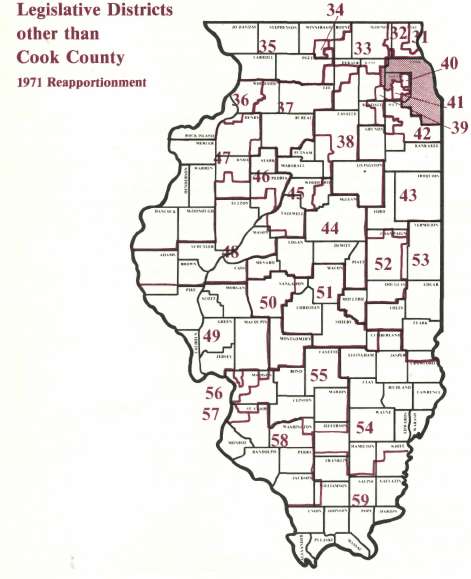

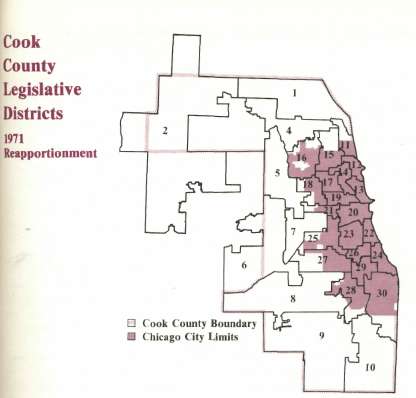

The bullet bites the dust: Will the Cutback Amendment bring competition and accountability? By DAVID H. EVERSON The Cutback Amendment was approved in November and thus ended an era. It brought an end to cumulative voting and will reduce the Illinois House. But will it fulfill its promises of greater competition and stronger accountability? It will for certain add to the 1981 reapportionment battle. REPUBLICAN Bernard E. Epton of Chicago was elected to the Illinois House from the 24th District in the 1980 election; he received 6.8 percent of the total votes cast in the district. At the same time, in the same district, Democrat Richard H. Newhouse was elected to the Illinois Senate; he received 99.9 percent of the total vote cast. These are extreme cases, but each suggests, in different ways, a lack of competition for legislative seats in Illinois. And results in other legislative districts, though not as extreme, clearly showed weak two-party competition. In general, the lack of strong competition for legislative seats undermines the principle of accountability to the electorate, and it is unlikely that either the "Cutback Amendment" or reapportionment will do much to alter this situation in Illinois. The 1980 legislative elections in Illinois set the stage for reapportionment — the biggest battle of the 1981 legislative session — and marked the swan song of cumulative voting and three-member House districts. The initiative or so-called Cutback Amendment was approved by 68.7 percent of those voting on the proposition, and thus ended a political era in the state. The Cutback Amendment will reduce the number of House members elected in 1982: one state representative will be elected from each of 118 new districts. In 1980, there were 177 House members elected, three each from 59 districts. In 1982, there will be no cumulative voting, that unique experiment in representative elections established in the 1870 Constitution. It was reaffirmed in the ratification of the 1970 Constitution when voters had the choice of changing the system to single-member districts in a separate submission. For over a century in Illinois, voters in each legislative district have elected three representatives by the method of cumulative or weighted voting. The Cutback Amendment has eliminated the system. Although the Cutback Amendment was an effort to reduce the size of the Illinois General Assembly, in reality, there were two issues: size and accountability. The critical argument was about the virtues of one system of representation over another in terms of political competition and electoral accountability. While the 1980 election resulted in the ratification of the Cutback Amendment to end one era, the 1980 Illinois legislative elections showed a definite swing to the Republican party, which appears to be entering its own new era. It was a Republican year in the nation and state, and the effects of that broad electoral tide were felt in Illinois legislative races. The Republicans gained control of the Illinois House by a 91 to 85 margin. (One independent incumbent, Taylor Pouncey, was elected in the 26th District, but he always sits with Democrats.) The Democratic edge in the Senate was narrowed to one vote which gave them the bare constitutional majority of 30. In both House and Senate races, the share of seats gained by the Republicans was proportional to their share of votes cast. In the House elections, the Republicans received 51 percent of the two-party vote statewide and 51 percent of the seats. In the Senate, with 20 seats to be decided, the Republicans received 52 percent of the votes cast and 50 percent of the seats, Republican coup It was assumed from the election outcome that the 82nd General Assembly would have the Repubhcans in control of the House and its leadership, faced off against the Democrats in control of the Senate and its leadership. The Republicans, however, seized control of leadership in the Senate January 15 with Gov. James R. Thompson as presiding officer. The power struggle in the Illinois Senate further complicates the situation for decisionmaking in the Illinois General Assembly. There was already a question of how divided control of the 82nd General Assembly would complicate reapportionment, but if reapportionment in Illinois has appeared to be a thorny issue in previous decades, it now appears worse for 1981. In 1963, when the Republicans controlled both houses of the General Assembly, they were eventually able to agree only on a House reapportionment plan. This plan was vetoed by Democratic Gov. Otto Kerner, and his action was upheld by the Supreme Court. Gov. Kerner, following constitutional procedure, then appointed a reapportionment commission, but when it was unable to produce an acceptable plan by its December deadline, Illinois had its first, and so far only, at-large legislative election. This was the famous 1964 "bedsheet ballot listing 236 candidates for 177 seats. In 1971, reapportionment was carried  10/March 1981/Illinois Issues In 1971, reapportionment was carried out according to the precise procedures in the brand new Illinois Constitution. With the Illinois Senate evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats and the House controlled by Republicans, the legislature was unable to pass a reapportionment plan before its deadline of June 30. As prescribed by the Constitution in Article IV, section 3, a commission was appointed. Composed primarily of legislative leaders and their aides, it did come up with an acceptable plan in the prescribed time. Although the Supreme Court objected to the makeup of the commission, the plan went into effect for the 1972 elections. In 1981, reapportionment by the General Assembly appears improbable. It takes a constitutional majority — 30 votes in the Senate and 89 in the House — to pass legislation, including reapportionment of state legislative districts. With both houses so evenly divided, and with different partisan majorities in each house, it may be difficult to arrive at the magic majority number or to get the two houses to agree to the same plan.

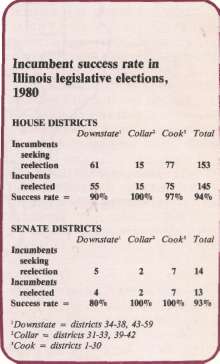

And the Cutback Amendment comes back into the picture again. With the cut of 59 House seats, there will be a lot of individuals jockeying to carve out new districts, and party loyalty may disappear as the predominant party attempts to sway individuals with "safe" seats in return for an "aye" vote on reapportionment. But it would appear almost impossible for the House majority leadership to find a plan which must cut out 59 of the incumbent 177 state representatives. It seems probable that reapportionment will dominate the session this spring, but that a commission, not the legislature, will decide on the plan. But if it is a sure thing the Cutback Amendment will complicate reapportionment, it is not much of a certainty that the Cutback Amendment will increase competition in House elections. Incumbents win The threat of electoral defeat is a major check on politicians, but that threat is only credible when there is an effective opposition. The advocates of the Cutback Amendment consistently argued that single-member districts allow for more electoral competition, and thus more accountability, than did cumulative voting. In particular, they argued that cumulative voting protected incumbents. Pat Quinn asserted in Illinois Issues in January 1980 that "the complicated and collusive election system is consciously designed to protect incumbents and limit political competition and accountability." But will electoral competition increase for House seats once the "cutback" election in 1982 is over? Once those 118 representatives are elected, will they, as incumbents, be safe in subsequent elections? The results of Illinois Senate elections, which have always been conducted in single-member districts, indicate that incumbents win. In the four elections from 1970 through 1978, 132 of the 150 incumbents who sought reelection were victorious (89 percent). And the 1980 Senate races were hardly models of competition. In November 1980, there were 20 state Senate races in Illinois. Four of these were reasonably competitive with the winner receiving between 50 and 54 percent of the vote. Two of the races were totally noncompetitive; Sen. Newhouse ran unopposed in the 24th District and Republican John E. Friedland ran unopposed in the 2nd District. That leaves 14 races which were not very competitive since the winner received 55 percent or more of the vote. In all, the average senatorial race was won by a 30 percent margin. How about the fate of incumbent senators? There were 14 incumbent Illinois senators seeking reelection in 1980; one lost (see table). That was Democrat Don Wooten of Rock Island in the 36th District; he was in the original group of liberal Senate Democrats called "The Crazy Eight." All in all, the success rate of lllinois' incumbent senators was about the same as the rate nationally for U.S. congressmen and much higher than U.S. senators. What about competition in House races? Although cumulative voting and multi-member House districts are now things of the political past, the last of those elections — 1980 shows much the same pattern of noncompetition as the Senate's single-member district races. One frequent indictment of cumulative voting as been the "set-up" where only three candidates are on the ballot for three seats. In 1980, eight out of 59 House districts had "set-ups." As a percentage of total races, this was 13 percent, just slightly higher than the 10 percent of Senate races where one candidate ran unopposed in a single-member district. Cumulative voting has also been criticized for making it possible to elect a representative with an extremely low percentage of the votes cast. Assuming the third place finisher in a four-person race with 15 percent or less of the total votes is a weak showing, then nine of the representatives elected to the House in 1980 got in on a pass. But this problem appeared to be limited to the heavily Democratic districts in Chicago, since all nine were from the Chicago area. They included eight Republicans and "independent" Pouncey of the 26th District.  March 1981/Illinois Issues/13 How safe were House incumbents? About as safe as Senate incumbents. In all, 153 House incumbents sought reelection in 1980. Of these, 145 or 94 percent were reelected. Of the eight incumbents who lost, six were Democrats: Richard A. Mugahan, 2nd District; Anne W. Wilier, 6th District; Gale Schisler, 48th District; John F. Sharp, 49th District; Vince A. Birchler, 58th District; and William L. Harris, 59th District. The two Republican incumbents who lost were Mary Lou Sumner in the 46th District and veteran Webber Borchers in the 51st District. The 94 percent success rate of House incumbents compares almost exactly with the 93 percent success rate for Senate incumbents. Evidently House incumbents were no safer than their Senate counterparts despite the "collusive" intent of cumulative voting.  New system, same results The conclusion is obvious. Do not expect the 118 single-member districts prescribed by the Cutback Amendment to produce more competitive elections than the old system. If single-member districts were automatically more competitive, the Senate results should differ dramatically from the House. This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that the new House districts will be smaller, and probably more homogeneous, than the Senate districts. In general, smaller districts which usually have less diverse interests, are less competitive than larger districts. Reapportionment will determine the shape of the new House and Senate districts, and it is very probable that the lines for many districts will be drawn to minimize competition. In other words, the tendency of pohtical parties is to reapportion "safe" districts for as many incumbents as possible. One other frequently noted effect of cumulative voting is that it has tended to maintain an even balance between parties in the House, and 1980 was no exception. Control of the House swung to the Republicans because of only five districts (8 percent). Four of those districts shifted from delegations of two Democrats and one Republican to the reverse. All four of these were south of Peoria. In four of these cases, an incumbent Democrat was replaced by a Republican. These four incumbents were Schisler (48th), Sharp (49th), Birchler (58th) and Harris (59th), and none of them had run first in the district in 1978. Despite the inherent resistance of cumulative voting to landslides for either party, it did "respond" to the Republican tide in 1980. Even though only a tiny percentage of the district delegations shifted in party balance, the Republicans gained control of the House. Republican gains in the Senate in 1980 put the Republicans one-vote short of a constitutional majority, which is required to pass legislation. The Republicans held onto all eight of their contested seats while the Democrats dropped two of their 12. Incumbent Wooten lost in the 36th District and George J. Lewis lost in the 48th District where incumbent John Knuppel (D., Virginia) did not seek reelection (he lost his bid for U.S. Congress). The Republican electoral tide of 1980 did not result in any clean sweep for Republicans in the state Senate, partly because only one-third of the seats were up for reelection. In 1982, however, after reapportionment, all 59 Senate districts will have elections. In 1982, without cumulative voting and with all state legislators elected from single-member districts, a party could experience a landslide if there again is a strong national surge.  The avowed purpose of cumulative voting, of course, was to allow minority party representation. The method of achieving this was the weighted vote; each voter had three votes. When a voter punched the ballot for only one candidate, that was a "bullet" counting as three votes. The voter could also divide his vote among two or three candidates. In fact, the election of a minority party candidate was all but assured since the majority party in each district typically nominated only two candidates. Bullet's distortion But the "bullet vote" also potentially allowed for the election of two representatives by the minority party — an obvious distortion of the intent of cumulative voting. Four districts in 1980 appeared to have done this. The voters of the 46th, 48th, 51st and 54th elected two representatives from the party which received a minority of the total vote cast in the district for representative. In each instance, however, the margin was so narrow (48 or 49 percent) that it would be extremely difficult to say with certainty which party was the "real" majority. Moreover, these "distortions" cancelled each other out. In two cases, the minority Republicans elected two representatives, and in the other two, the minority Democrats got the two seats. The analysis of the 1980 legislative elections in Illinois strongly suggests that reapportionment will be an intractable issue in the General Assembly in 1981 and that the Cutback Amendment will not result in increased competition for House seats nor in less safe seats for House incumbents. The only possible way that the new House districts might be more competitive is the minority party — whether Republican or Democratic — works hard in those districts strongly dominated by the majority party. The absence of cumulative voting might encourage this. Finally, despite the minimal amount of party change in both Senate and House elections in 1980, both elections showed a degree of responsiveness to the larger electoral wave in the nation. Both Illinois chambers moved in the Republican direction. If competition is to be increased in lllinois legislative elections, it will not come from the switch to single-member districts. Rather, it can only come from the revitalization of local party organizations, especially in the Chicago area, where the minority party has atrophied. David H. Everson is director of the Illinois Legislative Studies Center, Sangamon State University. The author acknowledges the research assistance of Nancy Biggs, Rita Harmony and especially Joan A. Parker. March 1981/Illinois Issues/15 |

|

|