|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By JAMES KROHE JR. The breaking of the prairie The revolution in farm technology, the introduction of high-yield hybrid seeds and the advent of artificial fertilizers are the major factors that helped transform Illinois prairie to Illinois farmland. Large portions of this farmland, in turn, have absorbed the massive urban exodus of the last 40 years — sprouting rows of houses instead of corn. All of these factors are explored in the following article, the second in a series of six articles on soil conservation funded by The Joyce Foundation.

ONE NEED merely review the vocabulary with which six generations of Illinoisans have described the settlement of the state to understand that the European newcomers saw the land as an enemy to be vanquished. The Indians saw the prairie and forests as a benefactor, and they practiced a benign tenancy of both. The white man, however, "tamed" the wilderness, "improved" the land, "broke" the prairie. Like the wolf, the mosquito and the Indian, the prairie and forest were regarded as inconveniences to be eradicated. The landscape of modern Illinois is as much an artifact of civilization as a superhighway. Although Illinois still calls itself the Prairie State, the prairie is long gone. Of the 37,000 square miles of prairie that once covered Illinois, only about two square miles remain. Of the estimated 14 million acres of forest that once stood in Illinois, only 3.5 million acres remain. In their place is an Illinois that has been systematically plowed, drained, paved, dammed, fenced, graded and regraded into more usable shapes. This artifact was built, however, using the most ancient of materials. The last of the great incursions of glacial ice into Illinois ended 10,000 years ago. Retreating glaciers deposited vast amounts of pulverized rock in the form of fine-grained, mineral-rich loess. This "glacial dust" lies as much as 200-feet thick in places and was spread by meltwater and wind into a blanket covering nearly the whole state. But loess is not soil, anymore than flour is cake. The topsoil whose fertility so amazed Europeans was the child of a happy marriage between the glacial till and the prairie ecosystem that took root on it. Wetter than the grasslands to the west, Illinois evolved into a tall-grass prairie covered with big blue-stem (which reaches a height of six feet), Indian grass, cord grass, little blue-stem, plus sunflowers, golden-rods, clovers, spurges and asters that in season set the prairie ablaze with color. Presumably to survive periodic droughts and fire, the perennials among them sent roots deep into the earth, forming a sod that was all but impenetrable to machines less efficient than gophers. Forests stood along streambeds, and hardwood groves, whose genesis remains a mystery to ecologists even today, stood isolated on the prairie itself like forested islands. Centuries of plant life added organic matter to the soil, and complex chemical and mechanical interchanges altered it to produce soils as close to perfect growing media as nature ever devised. Soils are as much a product of evolution as any animal species, and their ancestors can be deduced from their modern form. Lacking the dense root systems of the prairie, for example, soils that once underlay forested areas are generally lighter in color and more acidic than those that once sustained prairie grasses. The old 'Grand Prairie' The prairies and forests yielded up 425 different soils, according to modern soil scientists, each varying slightly from the others in mineral content, nature and extent of its subsoils, erodability and floodability, and proportion of clays, silts and sands. The ultimate criterion for the prairie's inheritors, of course, is its ability to grow crops; more than 21 million acres (roughly 60 percent of the state), most of them located on the old "Grand Prairie" that October 1981 | Illinois Issues | 19 once covered east central Illinois, are so highly productive that they are classed as "prime" agricultural soils. It is ironic that early settlers dismissed prairie soils as unfarmable on the ground that soil that could grow only grass must be infertile. Partly as a result of this notion, virtually all the state's timbered land had been claimed by 1835 while open tracts could still be bought from the government for another 20 years.

The presumed infertility of the prairie soil was only one reason why settlers avoided it. Farmers needed convenient sources of wood for fires and building and so settled in woods. Another problem of the prairie was the sod itself. The dense mat of roots simply turned aside plows. Early "prairie plows" built specially to turn that sod were made of cast iron, but they dulled easily and often broke. It was a tedious job since the heavy soil clung to the plow blade, requiring frequent cleaning. The task required up to six yoke of oxen; cutting a furrow roughly two feet wide and barely three inches deep; it took half a day to break a single acre. It was easier to fell trees and plow around the stumps. The prairie plows were moldboard plows, so named because of the curved board mounted behind the plow share which lifted the sod and turned it over, exposing the underlayers as it went. Designing a plow equal to the prairie sod was the key to unlocking the treasure locked beneath its surface. In the 1850s John Deere perfected a steel moldboard plow, and just as important perfected the mass production techniques that made it affordable. The Deere plow and its descendants cut more efficiently, scoured more cleanly and required less pulling power than older models. The steel plow was only the first in a series of mechanical innovations which Illinois farmers used as weapons to subdue the prairie. There were reapers, threshers, binders, riding plows and gang plows, and beginning in the mid-1800s with improvements in farm technology, more prairie acreage was put under cultivation. The breaking of the prairie sod was the crucial first step in the systematic exploitation of the state's virgin soils, but it was not the only one. Much of the prairie was swampy; a common nickname for malaria in those days was the "Illinois shakes." But in 1878 the General Assembly authorized the creation of local drainage districts with taxing powers, and by the 1880s a massive and expensive effort to tile fields

Farmers made other improvements on nature. Forest clearing continued, and levees were built to hold back floodwaters so that fertile bottomlands could be plowed. Eventually the rivers themselves would be channelized to boost their flow capacity and thus their ability to carry water away from what had been natural overflow basins. Wooden fencing had originally been another impediment to farming the prairie, since laying fence meant hauling wood long distances; hedges of osage orange were a popular alternative until they were replaced by cheap barb wire after the Civil War. By 1890, virtually all the land in the upper two-thirds of the state had been "improved." Farmland, in short, was made, not born. Once made accessible, the soil proved fabulously rich. Early chroniclers reported corn yields of up to 120 bushels per acre in the American Bottom opposite St. Louis; even indifferent prairie soils were said to bring in 50 to 80 bushels per acre. But this richness nearly proved to be the soil's doom. Believing the soil to be inexhaustible, farmers seldom practiced what was then called scientific farming. The benefits of both manuring the land and crop rotation (planting a cash crop on a given acre only once every three years and restorative forage crops the other two) were known but widely ignored. This casual approach to maintaining soil fertility also was partly the result of economics. By 1900 nearly 40 percent of the state's farmers were working land that belonged to somebody else. Historian John Keiser, writing in his Illinois history, Building for the Centuries, notes, "Short-term leases of one to three years gave the tenant little incentive to improve the land or experiment with crop rotation" — a fact of farm life which has not changed in 125 years. (One "baronial farmer" of Ford County in the 1870s required the continuous cultivation of corn by tenants on his 40,000 acres; it was during this decade that state agriculture officials and farm organizations began worrying publicly about the dramatic drop in soil fertility.) During the World War I era, Gov. Frank Lowden was to call such arrangements "a conspiracy to ruin land" and urged state legislation to compel more prudent cultivation habits. 20 | October 1981 | Illinois Issues Still, by later standards, farming practices of a century ago were fairly responsible. Crop rotation was practiced by many farmers, and much land was kept in pasture for draft animals. These habits not only helped bolster futility, but they stemmed soil erosion is well. As recently as 1900 most streams in Illinois could be described as dear-running except during spring Hoods. This is a remarkable fact, considering that by 1900 there were already some 20 million acres under the plow. Soil fertility was declining, but the soil itself remained largely intact, and with it the potential for renewal.

The arrival of the tractor Then came the tractor. Farming in Illinois had always been mechanized to some extent; to the farmer of the 19th century, the horse-drawn reaper was as much an improvement over the hand-keld scythe as the modern air-conditioned, stereo-equipped tractor is over the noisy two-cylinder machines of a generation ago. The result of the transformation from manpower to draft animals and then to stream and eventually petroleum energy on the farm made it possible to grow more food on less land using fewer people at a lower cost than ever before — but only if one does not count the cost to the land. Steam engines appeared on the farm in ihe mid-19th century; clumsy and heavy, they were used largely to power such things as threshing machines. Naturalist May Watts in her 1957 book, Reading the Landscape, notes that a steam-drawn gang plow capable of cutting 10 furrows at a swath appeared at a northern Illinois plowing contest in 1906. She cites a contemporary account: "It was likened to a Mississippi River steamer, plowing up waves, as it went down the field." Watts replied ruefully, "As plowing was made easier and easier, more and more Illinois soil would be drained away, until Mississippi River steamboats would, in time, actually be plowing through waves of prairie soil, but they would not need to leave the Mississippi to find that soil." The gasoline-powered tractor delivered on the promise made by the steam engine. Small and powerful, the tractor became popular in Illinois in the 1920s and '30s. The farm depression of the 1920s slowed its spread, but the tractor and its cousins like the combine were to revolutionize

World War II saw the final triumph of the new agriculture. Equipment such as tractors became widely available; new high-yielding hybrid seed varieties were also available, and perhaps most importantly, artificial fertilizers October 1981 | Illinois Issues | 21

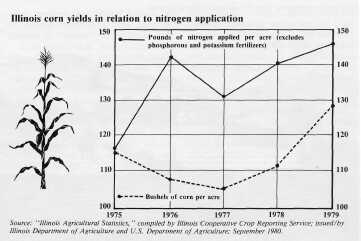

came into wide use. Virtually unknown in Illinois before 1940, these fertilizers, especially nitrogen, were being applied to the state's corn fields at an average rate of 117 pounds per acre by 1975 — and by 1979 at a rate of 146 pounds. Such applications boosted productivity marvelously, but in doing so masked the fact that most Illinois soils had been bled dry of their natural fertility. Soil was slowly becoming irrelevant to farming. The Mud Bowl Artificial fertilizers made it possible to abandon crop rotation without loss in yields. But the continuous cultivation of row crops left more and more land vulnerable to erosion. Illinois farm experts had first sounded the erosion alarm at the turn of the century, but to little effect. By the 1930s, the same combination of factors which produced the Dust Bowl in the Great Plains — continuous cropping and the planting of erodable land — created a Mud Bowl on the prairie. One government survey in 1932 found that reservoirs in the Galesburg region were filling up with 2.2 tons of sediment for every acre farmed upstream. Average rates of soil loss were less in the southern counties. But in those parts of southern Illinois where the land is steeply graded, the topsoil thin and the clay subsoils particularly uncongenial to plant life, farmers paid the ultimate cost of erosion: land voiding, or the abandonment of land so eviscerated that it can no longer sustain profitable farming. The Dust Bowl won the headlines in the '30s, but the wastage in Illinois was in some ways just as severe, even if the comparative wealth of original soil cover concealed the loss. Prodded by government conservationists working for such new agencies as the Soil Conservation Service, farmers built terraces on sloping land, plowed along the contour of sloping fields and planted water channels with soil-catching grass. But it was unclear what effect such reforms had on erosion rates. The more intensive cultivation that began in the 1940s may have played just as important a role in reducing erosion. Farmers planted the new hybrids earlier in the season and planted more plants per acre, thus giving fields a better protective blanket. The simple fact of overall higher productivity also helped indirectly; the government sought to trim surpluses in the '50s and

Farming in Illinois entered a new era in the 1970s. The cause was not a new revolution in farm technology; this time it was a revolution in farm economics. Other nations had a series of poor harvests, the U.S. government ended the set-aside programs — and consequently, U.S. export trade expanded. The need to absorb chronic U.S. grain surpluses and the calamitous rise in oil prices led to pressures to harvest more and more bushels through the more intensive use of land, machinery and fertilizers. More land was put into the cultivation of profitable row crops, including former "set-aside" land plus other marginal acreage such as pasturage and woods that had never been farmed. Although the land in farms in Illinois had dropped by some 700,000 acres between 1970 and 1979, the number of acres planted in corn or soybeans jumped from 17.1 million to 19.5 million. (Because beans leave behind a thinner residue, soybean fields tend to be especially erosive; soybean 22 | October 1981 | Illinois Issues acreage in Illinois increased from 1970 to 1979 from roughly 6.4 million acres to 9.8 million.) In addition to planting more land, farmers to whom a few bushels per acre meant profit or loss began fall plowing to save precious workdays in the spring. Bigger machines often are unable to follow the contour of the land, and terraces and grassed drainage ditches, installed during the Depression, were simply plowed over. The result: Soil erosion on Illinois farms jumped 10 percent. The pressure to farm more land pushed farmland prices to record levels; at a time when Illinois topsoil had never been worth so much money, its owners were treating it as if it were dirt.

Land as money Ironically, some of the same ecomic forces which led to what state farm officials have called the "mining" of the state's topsoil may force them to stop it. With fuel costs a major item in a farmer's budget, trips across fields in tractors are becoming more and more expensive. In an attempt to save energy costs, Illinois farmers are turning to one of the varieties of so-called "reduced tillage" methods of cultivation, which typically use a chisel plow instead of moldboard plow and rely on chemical herbicides instead of fall plowing and mechanical cultavation to control weeds. (In the "zerotill" system, the field is not plowed at all; seeds are planted right in the sod left from the previous year's crop.) The result is fewer field trips, lower fuel bills — and less soil erosion. Because crop residues are left in place both winter and spring, when soil losses are highest, erosion from corn fields can be cut by up to 50 percent. Many people are advocating reduced tillage systems for reasons other than soil conservation. The Illinois Environmental Protection Agency has been urging reduced tillage for several years because it reduces soil-related water pollution. Farmers, as noted, like it because it saves them money; the Illinois Farm Bureau recently urged its members, "Consider conservation to improve efficiency." Dismissed as quackery a few years ago, reduced tillage is now used on an estimated 4.5 million of Illinois' farm acres and may be the next revolution in Illinois farming, equal in its impact to the tractor or artificial fertilizers. Illinoisans public and private have always regarded land as money, to be spent on whatever they needed at the moment. Illinois, though a farm state geographically, has been an urban state demographically since 1900. After World War II especially, what Illinois has needed was cities.

In 1980, roughly 4 percent of Illinoisans lived on farms, compared with nearly 40 percent a century ago. This movement of people from the countryside into the cities is hardly unique, either to Illinois or to the late 20th century; the exodus began in Illinois in 1840. However, prior to World War II, urban population increases tended to show themselves in increased population densities in the cities. The costs of cities' growth — congestion, noise, disease — were paid by the people who lived in them. Since the 1940s, affluence has made detached single-family homes widely affordable, while the automobile has made accessible the land on which to build them. The result is lower population densities and the attenuation of urban development — "urban sprawl." The costs of cities' growth in the last 30 years have been borne by the land; for the first time in Illinois, cities became significant consumers of land. The result has been a predictable decline in the amount of Illinois land devoted to farms, from 32.8 million acres (92 percent) in 1900 to an estimated 28.5 million acres in 1980 (80 percent). (Estimates vary slightly according to one's definition of farmland.) The conversion of land from farm to urban uses (including reservoirs, roads and airports as well as subdivisions and shopping centers) may be leveling off, possibly because of declines in new building due to a sluggish economy. But even this apparent stability in the amount of land in farms may be deceptive; although "new" land is brought into cultivation to offset losses to urbanization, such land is often marginal land, while the land taken for urbanization is often prime farmland. Not all of these losses may be attributable to urbanization. In parts of the state, poor land that was being farmed 50 years ago has been abandoned and reclaimed by nature. This is especially true in southern Illinois, and in such a-typical corners upstate as Mason County's 1,700-acre Sand Prairie-Scrub Oak Nature Preserve, whose once-cultivated expanse has grown back with natural cover. Most of the four million farm acres lost since the turn of the century have been lost to cities. The very abundance of land in Illinois has caused people in become careless with it. Just as importantly, the urban constituents of governments at all levels have endorsed a body of land-use and tax law that is indifferent to, if not actually antagonistic toward, agriculture. Speaking at a 1980 Governor's Conference on the Preservation of Agricultural Lands, University of Illinois professor Clyde Forrest explained that in Illinois farm uses have been considered secondary to urban uses since 1908, and that Illinois law enshrines what is known as the "natural process of urbanization." Farmland conversion, however, can be explained by economics as well as by nature. Until fairly recently, farmland values generally were based on its agricultural October 1981 | Illinois Issues | 23 productivity. There have been episodes of land speculation, of course, usually following increases in land values caused by new technology which brought with it the promise of more efficient exploitation. But generally the value of farmland varies according to its ability to grow things. In 1930, the price per acre varied from $300 in the rich dairy country of northern Illinois to $180 in the corn-growing central counties to a paltry $20 in the hilly, clayey south; today the highest prices per acre are paid for the remnants of the rich Grand Prairie in east central Illinois.

As cities expanded, farmland near urban centers acquired a new kind of value. Developable land was assessed at its "highest and best use," as required by law. Taxes based on this higher assessed value were often more than the land could earn, which led to pressure from farmers to change property assessment law. Revisions in 1979 and again in 1981 made assessments of farmland a function of its productivity rather than its price. Such new assessment practices ease the property tax burden on farmers, and thus ease the pressure to convert land to more lucrative nonfarm uses. But inflated land values — prompted in part by speculative buying by non-farmers attracted by the quadrupling of Illinois land prices in the '70s — have other effects. Some are positive; an established farmer can borrow against his present holdings to buy more land. But inheritance taxes based on inflated land values forced many heirs to sell parts of farms to pay them. In 1976 the federal law was revised to exempt up to $500,000 of property from the tax by allowing farm estates to be valued for tax purposes as farmland and not at full market value. President Reagan's 1981 tax package, however, calls for phased increases in this exemption which will allow up to $750,000 worth of land to escape taxation by 1985. There is no inheritance tax at all on land bequeathed to a spouse (ending the so-called "widow's tax") and more generous post-valuation exemptions (up to $600,000 by 1987) and a reduction in the maximum tax rate from 70 percent to 50 percent promised to virtually eliminate federal death taxes on family farms. Illinois' own more modest tax (the maximum rate is 14 percent, compared to the federal maximum of 70 percent) was similarly liberalized that year. The exemption formula has shaved the tax bill for the average Illinois farm estate by $11,000, but even this is an insufficient economy in the view of the state's farm groups, which have been lobbying in the General Assembly for the outright abolition of the tax. The same worldwide grain shortage that sparked the intensified exploitation of the state's dwindling farm resource also awakened government to the limits of that resource. But preserving that resource means not just revising the law, but revising a century-and-a-half of attitudes toward the land and land ownership. Attempts to restrict private interest on behalf of the public interest are never easy, especially when that public interest is long-term and only vaguely perceived, and the private interest is immediate and entrenched. A dwindling resource While government looks for solutions, the pressures on the land continue only slightly abated. High energy costs are compelling farmers to till their land with a gentler hand, but the global food economy still demands high production from that land. High energy costs also may restrain the outward expansion of cities, but the social forces propelling that expansion — fear of crime, high taxes, crowded or inferior schools, to name a few — show few signs of easing. Until they do, Illinois is likely to continue acting as if the prairie still had to be broken. James Krohe Jr. is a contributing editor to Illinois Issues and associate editor of the Illinois Times in Springfield; he specializes in planning, land use and energy issues. 24 | October 1981 | Illinois Issues |

|

|