|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Can Big Jim beat the third term jinx?_____________ By PAUL M. GREEN Jim Thompson's extraordinary record as a vote-getter makes him an odds-on favorite to be the first Illinois governor ever to serve three terms. But Thompson has never faced such a formidable opponent before. Adlai E. Stevenson III is heir to one of the state's most powerful political legends, and despite his fabled lack of campaign skills, he could win in a close race. Or rather, Thompson, with some help from the recession, could lose it.

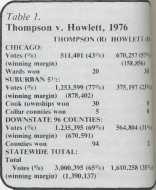

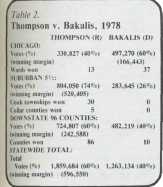

CAN Jim Thompson become the first governor in Illinois to be elected to a third consecutive term? This question looms over the Illinois political scene as both parties begin to organize their forces for the 1982 elections. Indeed, far more than Thompson's future will depend on the voters' response to his historic third term bid. In 1982 the entire redistricted and cutback Illinois legislature will be up for grabs, as will all major state offices. Despite increased ticket splitting in Illinois, most political pros agree that Thompson's performance at the top of the ticket will have a large effect on the election of others on the ballot. Republican and Democratic candidates throughout the state are already asking the same question: Can "Big Jim" do it? Third term attempts Only one Illinoisan has been elected to the governorship three times. Richard J. Oglesby, a Republican lawyer-farmer from Macon County, won the state's top post on three occasions — 1864, 1872 and 1884, but he served a term as U.S. senator, and barely started his 1872 gubernatorial term. In his third victory Oglesby defeated Chicago's popular Democratic mayor, Carter H. Harrison, by a very slim margin. Harrison, a charismatic campaigner, never made an issue of Oglesby's unprecedented third term quest. Rather, he claimed that Oglesby was anti-Chicago. On election day Cook County voters (who were almost entirely Chicago residents) gave the downstater a narrow victory over the mayor. For the next 60 years no Illinois governor sought a third term. Then, in 1948, Republican Gov. Dwight H. Green of Chicago attempted to become the first man in Illinois history to win a third consecutive term. In this classic contest, the Democrats put up a virtually unknown suburban lawyer (with some downstate roots) to challenge Green; his name was Adlai E. Stevenson II. Stevenson trounced Green by a surprising margin, thereby aiding his fellow ticketmates, President Harry S. Truman and senatorial candidate Paul H. Douglas, economics professor and former Chicago alderman. The three led Illinois Democrats to one of their greatest election victories in the 20th century. The press made little note of the third term effort and generally limited their remarks to the voters' general dissatisfaction with Green and the charming family of the new governor-elect. Twelve years later another Republican governor attempted to win a third straight term, William G. Stratton, the "boy governor" who had pushed through the state's first legislative reapportionment in over 50 years. Stratton, an astute politician, was adept at political horse trading with Chicago's powerful Democratic Mayor Richard J. Daley, and he pulled out all the stops in his campaign. (He was the first Illinois candidate to fly around the state using a helicopter.) Stratton's opponent was a suburban lawyer, Otto Kerner, son of former Atty. Gen. Otto Kerner Sr. Kerner demolished Stratton's dream of a third term by scoring a landslide victory. For the first time commentators wrote of a third term jinx, but most pundits agreed that Stratton's loss had little to do with this fact. Rather, the press zeroed in on Stratton's divisive renomination primary fight with south suburban conservative Republican Hayes Robertson as the key factor in his defeat. 6/January 1982/IHinois Issues The press also gave a great deal of attention to the fact that the Republican state auditor, Orville E. Hodge, an elected state officeholder, had been convicted of embezzling state funds during Stratton's term in office. Stratton was in no way implicated in the scandal, but the Hodge affair occurred during his administration and hurt his bid. Also during Stratton's second term, Atty. Gen. Grenville Beardsley died, and the governor named William L. Guild of DuPage County as his successor. Guild and Elbert S. Smith, Hodge's elected successor, ran uninspired election campaigns and were easily defeated by Chicago Democrats William G. Clark and Michael J. Howlett. Thompson, like Stratton, will be running with two of his appointees, Secy, of State Jim Edgar and Atty. Gen. Tyrone Fahner. And as with Stratton, Thompson appointed one of his running mates (Fahner) to replace a former running mate convicted of a felony (former Atty. Gen. William J. Scott). But the situations of Thompson and Stratton are not identical: Thompson was not pressed in his first reelection bid as was Stratton. Thompson's first two An analysis of the 1976 and 1978 election returns reveals remarkable ap-prova! of Thompson outside the city of Chicago, and even in Chicago Big Jim has done well for a Republican (see tables 1 and 2). Thompson has used his law enforcement background, his ex-perience as U.S. district attorney and a folksy campaign personality to politically bury Democrats Michael J. Howlett in 1976 and Michael J. Bakalis two years later. In both campaigns, forces outside Thompson's control aided him immensely. Mike Howlett in 1976 was the popular Illinois secretary of state who, with the urging of Chicago's Mayor Daley, challenged incumbent Gov. Dan Walker in the Democratic primary. In an exciting and bruising congest Howlett captured the nomination, but in so doing, he was politically wounded by Walker's aggressive campaign. On election day in November the voters flocked to Thompson and gave him the largest percentage victory margin in Illinois gubernatorial history. In 1978, state Comptroller Mike Bakalis challenged Thompson. Bakalis, an energetic campaigner, searched for an issue to capture voters' attention. He attempted to latch onto the growing tax revolt mania which had exploded on the national scene with the passage of California's Proposition 13. Bakalis seemed to be making some headway when Thompson took away the issue by calling for a public advisory referendum on limiting government spending. The governor shrewdly called his resolution the "Thompson Proposition," and after some minor problems getting the measure on the November ballot, he was successful in making the tax and government limitation issue his own. On election day the voters gave Thompson another landslide win, although his margin was smaller than in 1976.

Chicago's vote Jim Thompson lost the city of Chicago in both of his gubernatorial campaigns. Even in losing, however, he showed remarkable strength on Chicago's middle-class northwest side and among independents along the lake. In 1976 he carried five of these 13 wards with over 60 percent of the vote, and in 1978 he maintained this remarkable strength in two of these wards — the heavily Polish 41st and the near north lakefront 43rd. In both elections Thompson's weakest Chicago areas were the 15 black wards on the west and south sides, and the Democratic party's city bastion, State's Atty. Richard M. Daley's 11th ward. In 1976 the battered Howlett campaign won 30 of the 50 Chicago wards, and in 18 wards he carried 70 percent of the vote. Two years later Bakalis won 37 wards and increased the 70 percent wards to 20. Bakalis also increased the Democratic gubernatorial vote in Chicago from 57 percent to 60 percent, and despite the reduced turnout in the off-year election, he bettered Howlett's margin by 7,500 votes. Percentage-wise, Bakalis made the greatest inroads into Thompson's city vote in Chicago's southwest and near northwest side ethnic wards. However, Bakalis was unable to cut significantly into Thompson's previous strength in the northwest side and lake areas, nor into Thompson's strength in the wards on Chicago's north side. The 11th Ward has hurt Thompson the most in both elections, but because the governor has done well in several wards where turnout was heavy, he has kept his Democratic opponent's citywide vote margin relatively low. In contrast, the best wards for Howlett and Bakalis (outside of the 11th) have been mainly the wards with lower turnout on the west and south sides. Can Chicago play a major role in defeating Thompson in 1982? Judging by past returns, turnout rates and the recent census, the answer is probably not. If the Democratic gubernatorial candidate in 1982 increases the Bakalis city vote by 10 percent and the rest of the state turns out and votes as it did in 1978, Thompson would still carry Illinois by over 430,000 votes. In other words, a Democratic candidate can win 70 percent of Chicago's vote (a percentage higher than Jimmy Carter's in his 1980 race against Ronald Reagan) and still lose the state by a landslide. The suburban vote In his two previous gubernatorial campaigns Thompson has steamrolled his opponents in the suburban 5 1/2 counties — DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry, Will and Cook County outside Chicago. Not only has Thompson never lost a suburban Cook County township or a collar county, but he has, almost unbelievably, received 60 percent or better in every township (except Stickney in 1978). In 1976 the suburban 5 counties gave Thompson a vote margin five times the size of Howlett's in Chicago, while in 1978 Thompson's suburban margin was three times larger than Bakalis' city margin. In 1976 Thompson won nine of 30 suburban Cook townships with over 80 percent of the vote. His weakest township was Stickney, where he had to settle for a mere 65 percent victory over Howlett. Thompson's best winning margins were in the fast growing, heavy turnout northwest suburban townships. It should be of some interest that in 1976, Thompson's margin in Wheeling Township was greater than Howlett's combined margin in the latter's three best city wards. January 1982/lllinois Issues/7 In 1978, Bakalis barely reduced Thompson's impressive suburban Cook vote. In more than half of the townships Thompson held his percentage to within 2 percent of his 1976 vote. Thompson received margins of 80 percent or better in six townships and won by 70 percent in two-thirds of the townships. Thompson did even better in the five suburban collar counties. In 1976 no collar county gave Thompson less than 72 percent of its vote, and in 1978 only Will County (67 percent) came in under the 70 percent figure. These fast-growing, vote-producing areas have provided the governor with spectacular totals. In 1976 Thompson's DuPage County margin, by itself, nearly matched Howlett's in Chicago. In 1978 Thompson's winning margin in the combined collar counties was 40,000 votes greater than Bakalis' winning margin in the city.

In short, Thompson's suburban 5 1/2 power greatly surpassed his Democratic opponents' strength in Chicago. In 1976 Thompson came out of the six Chicagoland county area with a lead of over 700,000 votes, while in 1978 these same counties gave him a 350,000 vote cushion. Obviously, if a Democrat is going to seriously challenge Jim Thompson in 1982, he must cut drastically into the governor's suburban 5/2 strength. No candidate can withstand such lopsided returns from a region that cast 35 percent of the statewide vote in both, the 1976 and 1978 gubernatorial elections. It does not take a great deal of political acumen to realize that unless the 1982 Democratic gubernatorial candidate, Adlai E. Stevenson III, can develop some suburban appeal and reduce Thompson's percentages by 10 to 15 percent, his campaign will be hopeless. The other 96 counties In the last two gubernatorial elections, downstate voters have generally mirrored the total Illinois vote for both major party candidates. In 1976 Howlett was able to carry only two small southern Illinois counties, Alexander and Gallatin. Bakalis, two years later, won 10 counties, none of which was north of Macoupin County, and except for St. Clair and Madison all of them were low turnout counties. On the other hand, Thompson has virtually owned central and northern Illinois in both of his previous elections. Against Howlett, eight of these counties gave him over 80 percent of their vote, while another 34 were in the over 70-plus percent range. In 1978 Bakalis cut into Thompson's down-state totals by reducing the governor's winning percentage nearly 10 percent overall. Bakalis made inroads into Thompson's strength in western Illinois and picked up some votes in the southern part of the state; he even whittled down Thompson's strength in the northern counties of Winnebago and Lee. But Bakalis' improvement has to be measured against the near astronomical totals that Thompson racked up against Howlett in 1976. Thompson's downstate strength has been broad and deep. He has done especially well in more populous downstate counties and in counties containing large university towns. The counties where he had the largest winning margins in the 1978 contest were all large counties, three of which (Champaign, Sangamon and McLean) have state universities. In summing up Thompson's overall political strength in Illinois, one is struck by the consistency of support in both elections. In the 1978 gubernatorial election, Cook and collar county voters cast 62 percent of the total state vote. In not one of these vote-rich counties did Thompson's winning percentage drop more than 5 percent from his dazzling 1976 totals. Thus, Thompson is an extremely for midable political force in Illinois, and the Democrats will not easily push him out of the state mansion.

Democrat chances in 1982 For the Democrats to short-circuit Thompson's third term bid, their can-didate must be able to cut into his totals in the suburban 5 Vi counties as well as the downstate 96 counties. A substantial vote in Chicago alone will not give the Democratic candidate the necessary votes to overcome the GOP's pluralities in the other two regions. At first glance this may seem impossible but it must be remembered that the three gubernatorial races before Thompson's 1976 win were all ex-tremely close. Dan Walker in 1972 and Richard B. Ogilvie in 1968 won with only 51 percent of the vote, while in 1964 Otto Kerner defeated Charles H. Percy, 52 percent to 48 percent. 8/January/1982/Illinois Issues

Sorting through the names of those most mentioned as possible 1982 Democratic gubernatorial candidates, it seems clear that the one person who stands a chance of defeating Thompson is former U.S. Sen. Adlai E. Stevenson III. He has the name recognition and reputation to give the governor the race of his political life. The two other major Democratic alternatives, 1978 U.S. Senate candidate Alex Seith and former Gov. Dan Walker, simply do not measure up to Stevenson as a challenge to Thompson. Seith ran a credible campaign against Percy three years ago, but he still lost the contest by over 250,000 votes. Seith's pugnacious and often irritating campaign tactics would be a setup for Thompson, a champion political coun-terpuncher. Moreover, Seith's low political visibility since 1978 leaves him without a constituency to take on a two-term incumbent governor. As for Walker, he may have become a political anachronism whose considerable campaign skills are no longer viable. In 1972 a relatively unknown Walker won the governorship by defeating two popular Illinois politicians, then-Lt. Gov. Paul Simon in the Democratic gubernatorial primary, and incumbent Republican Gov. Ogil-vie in the general election. In office Walker became known as a confronta-tionist who challenged political tradition by his seemingly endless warfare against almost everyone. Today his cut-and-slash rhetoric seems dated. For example, his attempt to make an issue of Thompson drinking with college students at a football game hurt rather than aided his cause. Perhaps 10 years ago Walker could have gotten some political mileage out of this event, but in 1981 his telegram to Thompson expressing outrage over the incident hardly was considered "the schnapps heard round the state." Stevenson, on the other hand, has a proven election track record and a near-mystical ability to attract suburban and downstate voters. In his last Senate race in the Watergate year of 1974 (against an admittedly weak Republican opponent, George Burditt) Stevenson piled up impressive vote totals throughout Illinois. In fact, during the past decade he and current Illinois U.S. Sen. Alan J. Dixon have been the only Democrats to run consistently well statewide.

Obviously, Stevenson benefits from being the heir to a magical name in Illinois politics. His family has been on the state and national scene for three generations, and the current Stevenson has been perceived as a hardworking, honest public official. But although his father was a talented phrase-maker who intellectualized American political speechmaking and turned it into an art form, young Adlai (as he is still called) seldom utters a memorable line. On the political stump Stevenson breathes little fire and plods through his speeches. Yet for inexplicable reasons, Stevenson's unspectacular style has not diminished his support throughout the state. He seems to have made tranquili-ty a political plus and is the only Illinois politician who benefits from a lack of charisma. A 1982 Thompson-Stevenson gubernatorial race would pit political op-posites. Unlike his past campaigns, this time Thompson will have to run a straight issue campaign. And the governor will not be able to call Stevenson a Chicago machine politician (as he did Howlett in 1976) or dominate the campaign with a gimmick (as he did in 1978 with his Thompson proposition). On the other side, Stevenson needs to convince voters that he is well-versed in state affairs. He must also not identify himself too closely with Democratic interests. Here again, the typically hazy quality of a Stevenson campaign may serve him well. There are, of course, many unexpected events that can alter political strategies, and the final outcome of the election is still almost a year away. For Thompson, the fate of Reaganomics may play a key role in his third term bid, as may the GOP primary for lieutenant governor, in which anti-Thompson state Sen. Donald L. Totten is pitted against Thompson-chosen House Speaker George H. Ryan. A Totten victory could have a significant influence on Thompson's campaign. A Thompson-Totten ticket would require political acting equal to anything now playing in Washington. Stevenson is also faced with several political uncertainties. The most important is the possibility of civil war in the Democratic party between Chicago's Mayor Jane Byrne and Cook County State's Atty. Richard M. Daley. Informed sources earlier this year labeled Stevenson as Daley's gubernatorial candidate, but Stevenson, in his own inimitable fashion, has publicly eased away from this identification. It is no secret that Byrne (and probably Daley) views 1982 as an exhibition season for the big game: the Chicago Democratic mayoral primary in February 1983. Prediction Those who have read some of my earlier articles in Illinois Issues know that my previous political predictions have not been perfect. Michael Bilan-dic is not the mayor of Chicago, as I said he would be. Nevertheless, I venture the following prognostication about Jim Thompson's historic third term election bid: Stevenson simply does not have the potential votes to take it away from him. Thompson can be defeated only if Thompson thoroughly bungles his campaign and strong forces outside his control work against him. In short, Stevenson cannot win January 1982/Illinois Issues/9 the election, but it is possible for Thompson to lose it. To show how bleak the numbers look for Stevenson, imagine the following scenario: Thompson somehow blunders in the suburban 5 Vi, allowing Stevenson to up the Democratic gubernatorial vote 10 percent above the 1978 totals; the city of Chicago turns violently against the governor and supports Stevenson (the way it supported Carter against Reagan), thereby adding another 10 percent to the totals achieved by Bakalis. All these favorable events would still not add up to a Democratic victory; it would be a neck-and-neck race going into the downstate stretch, and downstate would be the key. Right now — one year before the 1982 general election — I believe it would be impossible for Stevenson to beat Thompson downstate.

Nevertheless, Thompson does not have his third term in the bag. Just as Stevenson has never faced a candidate like Thompson, Thompson has never faced a candidate like Stevenson. A major miscalculation by the governor on the transportation issue or a severe national economic recession might so sour the voters that Thompson's support would be eroded enough in both the suburban 5Vi counties and the 96 downstate counties to elect Stevenson governor. This would keep alive the gubernatorial third term jinx.D Paul M. Green is chairman, division of public administration, and director, Institute for Public Policy and Administration, Governors State University, Park Forest South. Author of several articles in Illinois Issues, Green has also contributed a chapter in a forthcoming work on Illinois reapportionment to be published by the Institute of Government and Public Affairs, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. 10/January 1982/Illinois Issues |

|

|