|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Higher ed: less money, fewer choices By DIANE ROSS The most optimistic estimates of the future of higher education in Illinois are marked by uncertainty. Both public and private institutions will be seriously affected by upcoming federal reductions in student aid and the inability of state government to find the new dollars needed to attract and retain quality faculty and to guarantee access to middle-class students. Although Illinois is in much better shape than states such as Washington and Michigan, it is clear that the lean years are here. THEY'RE playing that television commercial again: The one in which William Shakespeare, sporting ruff, doublet and hose, strolls through the cloister, unnoticed, passing students on their way to class, lamenting the state of affairs in higher education, pleading for you to support the college of your choice. Never hath The Bard more verity. Higher education is in trouble. In Illinois, the recession has forced Gov. James R. Thompson to cut the increase in spending to balance the state budget. And if the recession continues, it may force him to cut back spending even further to keep Illinois solvent. Yet the demand for higher education in Illinois — in these times of unemployment — has never been greater. Enrollment is up this year at Illinois' 10 state universities, 52 public community college campuses and more than 50 private schools. Clearly, the financing of higher education in Illinois has reached a crisis, a situation which Richard D. Wagner, executive director of the Illinois Board of Higher Education (IBHE), defines as "the most significant fiscal challenge we've experienced." There is widespread agreement that the quality of higher education in Illinois is still relatively high. But there is an equally widespread fear that quality as it now exists will not survive this crisis. Isolated voices still contend that the lack of money won't seriously affect quality. But the vast majority maintain that: "We can't improve quality; we can't maintain quality; and if the crisis continues much longer, quality will deteriorate." So says, for example, Carol Elder of the University Professionals of Illinois, the largest of the faculty unions. The IBHE says that the state universities, community colleges and private schools are holding their own in the increasingly mad scramble for fewer and fewer state dollars. Wagner says, "I think that within the context of the resources available, the governor and the General Assembly showed great sensitivity to higher education requirements [in fiscal 1982]. In my judgment they should be complimented for that. "Now that's not to say that we're not going to have sacrifices within higher education. That's not to say there aren't internal reallocations required. That's not to say we're not going to have to improve our productivity. "The uncertainty of the future is what's going to be very difficult to deal with." Faculty, however, generally don't think higher education should be quite so ready to take what the state dishes out. If the public is returning to college because of unemployment, they ask, how can the state pursue a policy that seems to be closing the doors of higher education? Some, like Elder, are demanding that the state reexamine its priorities now, before it is too late, arguing that Illinois may find one day that it took its universities for granted. "The question of whether we're cutting back should be discussed as a question; it shouldn't be taken as a given," Elder says. "It's precisely at this point that there's a possibility of retraining people [to reduce unemployment]. Perhaps we ought to make more of an investment in higher education. Nobody's talking about that; they're talking about cutting back." The recession may have touched off the crisis, but faculty suggest that the current state of affairs in higher education today is the symptom of a deeper, more alarming malaise. "This is the consequence of a highly complex, in-dustrial-technology society deciding it doesn't want to invest in the education of its children," says Martha Friedman of the American Association of University Professors. "This is not even a guns versus butter issue," Fried-man says, "although higher education was once a weapon in our defence policy. "We cannot hope to operate a coun-try like the United States without a sizable cadre of well-educated people," Friedman says. "How on earth are we going to cope with the incredible prob-lem of toxic waste if we don't have people who can understand it? What would happen to the Illinois economy if there is a good, cheap way to get the sulfur out of Illinois coal?" Some legislators, to Friedman's relief, say they are worried that the literal definition of higher education will be lost in the fiscal shuffle, that the expansion of knowledge will cease, that research in the humanities will be forgotten. "The IBHE does a fine job of analyzing data," Elder says, "but they do not act as advocates in the way we want them to act. The faculty wants them to take the lead in reexamining policy." Friedman's not sure there's time. "If we continue to have a reduction in taxes and we continue to have a recession . . . how is the State of Illinois go-ing to be able to continue to do all the things it's doing now? Something's got to give. "I don't think there will be a single new dollar for higher education in the next fiscal year," Friedman says. What's going to happen when the state can no longer afford to increase aid to higher education? If the state ac-tually decreases aid in terms of dollars?  NOTE: Means growth in compensation for all ranks, reflecting the fiscal year 1981 mix of faculty among ranks. Source: Compensation in Illinois Institutions of Higher Education, Item #6. 12/January 1982/Illinois Issues Faculty say less state aid means there will be no hope of replacing library books and obsolete laboratory equipment, much less raising faculty salaries that are now barely competitive with those in other states. The apparent brain drain from Illinois may become an actual shortage of faculty. That would mean more students in less classes — eventually raising standards for admitting students and lowering standards for hiring faculty. Students say less state aid means an increase in tuition and a decrease in financial aid. One probable result is that middle-income students would no longer have access to higher education — much less choice. Would only the very rich and the very poor be able to afford college education? That would strike at the heart of higher education in Illinois, its diversity, threatening the survival of the community colleges and the private schools.

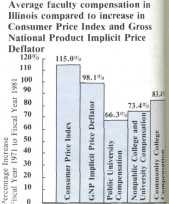

Just how serious is the situation? So serious to students that they suggest willingness to pay more in tuition if they could be assured of more in financial aid. So serious that some faculty, at least, suggest that they may one day take a cut in pay if it is necessary to save the universities. Beyond the implications to higher education are the effects on the state's economy. "I think that the people of the State of Illinois have made a significant investment in higher education," Wagner says. "And it's critically important that we maintain and improve that investment. "That's going to require that the institutions, the systems, and the Illinois Board of Higher Education take a good, hard look at how we're using our resources. That's going to require that the people of the state, through the governor and the General Assembly be sensitive to the needs of higher education. "I feel good in my judgment that the Illinois Board of Higher Education is pell respected by the governor and the [General Assembly ... by the institutions. It has a track record, a proven track record, of being willing to make tough decisions. That speaks well for the board. Gracious knows we're going to have a lot of opportunities." Faculty say one such opportunity will come with faculty compensation, an issue Wagner acknowledges as "critically" important. Students say another will come with tuition and student financial aid. Faculty compensation If the recession continues and the state is forced to actually cut spending, faculty may no longer get annual raises, their salaries may be frozen, they may be laid off, their positions may be eliminated, tenured and non-tenured alike. That hasn't happened in Illinois yet, but it has in other states, Washington and Michigan, for example. "There's no sense of impending crisis, but it certainly is something that is within the realm of possibility," says Elder, a member of the English faculty at Eastern Illinois University, who is vice president for the Board of Governors Council of Local 4100, AFT, IFT, AFL-CIO, of the University Professionals of Illinois. "I think we're coming to the point when faculty compensation will have to be displaced as a top priority," warns Friedman, a member of the library science faculty at the University of Illinois, who has served as local, state and national president for the American Association of University Professors. "You can't run a university for decades without equipment," she says, arguing that some equipment was obsolete before the crisis struck. "There are people who would stone me to death for saying this," Friedman says, "but if we were faced with the situation they are in Washington, I would prefer that we have a salary reduction rather than wreck the universities. "During the depression, faculty struggled mightily to keep the good old light of higher education burning," she says, adding that the old policy of "dry" promotions without pay is a strategy not even publicly discussed now. "It is a drastic measure, but I submit that people in universities have a social responsibility which is a very important one. We cannot permit the universities to be wrecked, if that means we can't compete, then that will have to be." In the last decade it has become increasingly clear that Illinois is no longer competitive, in either the public or the private markets, in terms of compensation. There are those who say higher education has never been able to compete with the private sector, but even they agree that inflation has widened the disparity to the extent that higher education is no longer able to compete with the so-called public sector, state government, and thanks to the recession, state universities in Illinois are barely able to compete with those in other states. The situation is worse in state universities than it is in community colleges or private schools. In terms of inflation, the IBHE says, the Consumer Price Index rose 115 percent between fiscal 1971 and fiscal 1981: compensation at state universities rose only 66.3 percent, while that at community colleges rose 83.4 percent and that at private schools rose 73.4 percent. In terms of other states, the IBHE says compensation at state universities in Illinois during academic year 1980-81 was 7.2 percent below the national median when adjusted for inflation, 3.6 percent below when unadjusted. Salaries alone were 4.9 percent below the median, .8 percent below when unadjusted. At Illinois community colleges, however, compensation was above the median; at Illinois private schools, at or slightly above. Consequently, Illinois is losing the best and the brightest of its faculty — the so-called brain drain. Generally, Illinois loses its business and science faculty to state government and public universities in other states, particularly those on the East Coast and the West Coast where salaries are the highest. Although the extent of the brain drain has yet to be documented, a trend could develop. In the 1970s, Illinois could still attract quality faculty, but lately, as salaries lagged behind other states, the attraction has diminished. If compensation continues to fall further behind, Illinois may not be able to attract quality faculty in the 1980s. In some of today's markets, students fresh out of college can command as much — or more — in their first year with private industry as faculty can after years in higher education. "There are increasingly fewer rewards for imaginative, highly qualified people to choose [higher education] as a career," Elder says. "Obviously you have to have a kind of dedication to the service January 1982/Illinois Issues/13 to others," she says, "or you wouldn't be in the field at all. But faculty need to send their own kids to college." "I think it's a universal problem," Friedman says. "The news of the depression in higher education is national; it is known. The quality of faculty available is deteriorating. This hasn't been documented yet, but this is what everyone thinks." Until now, compensation was always a matter of when — not if — Illinois will become competitive again. But because state revenues are sagging, Wagner says the state will be hard-pressed to finance annual raises next year (fiscal 1983). "It may well be that the salary increase will be given, but that the people would have to finance it internally, in their departments, that is, abolish positions," Wagner says. "I think the trade-off is going to be ... 'What average faculty/staff salary increase do you want to give?' and 'What price are you prepared to pay in terms of not filling positions?' Now this past year we financed at least 1 percent [one-eighth of the annual raise] internally." Elder says the suggestion that annual raises ought to be financed through attrition is "unrealistic." "That oversimplifies the problem," she says, arguing that the number of positions vacated each year is low to begin with, and some of them must be filled. But Friedman says attrition-financed raises, in effect, are nothing new. "We've been cannibalizing for years," she says, explaining that faculty has always reallocated positions to meet enrollment demands. "It just hasn't had to be done to the extent it has to be done now," she says.

Some legislators agree with Wagner that keeping salaries on a par with inflation is almost a lost cause. But others say the state can afford to finance annual raises — and the legislature will increase state aid accordingly — if faculty at public universities can convince legislators they are worth it. "We can't afford to pay people a salary commensurate with their expertise and knowledge when they're only going to be teaching for 10 hours a week," says Rep. Sam McGrew (D., Galesburg), minority spokesman on the House Higher Education Committee. "I don't think the state is getting its money's worth from the current teaching load," he says. "That's not true across the board, but it's certainly the case in some areas," he says, charging that the teaching load has gone down while salaries, competitive or not, have gone up. Faculty find the teaching load charge ludicrous in light of the expanding enrollment and resulting increase in credit hour production. "1 certainly know of no place where 1 think that would be true," Elder says. "People are teaching heavy loads. We certainly put in a full day although it's not all in the classroom. I'm not sure everyone understands what is involved in teaching." "Legislators have this hang-up that if you teach eight hours a week you only work eight hours a week," Friedman says. "The administrations do not run the universities," she says, "the faculties do and that takes time." But legislators raised another issue that strikes a little deeper: research versus teaching. "Some of our top-paid professors haven't seen a graduate student in 20 years," charges Rep. Jim Keane, a Chicago Democrat whose opinions on higher education are sought by staffs on both sides of the legislative aisle. Keane argues that the theory that quality faculty attract quality students doesn't always work in practice. He questions whether such "top-paid professors" are cost-effective, suggesting that universities might be forced to offset more expensive research faculty with less expensive teaching faculty. "Research is part of what faculty do because it's essential to their teaching," Elder says. "Legislators forget the amount of money faculty contribute to education," Friedman says, arguing that research attracts grants. "When you have to teach more, it cuts down on the research money you can bring into the universities." Tuition and fees, not financial aid, has always been the No. 1 issue among students. But the crisis higher education faces has already changed all that. State support has kept tuition low, at least at state universities and community colleges. Federal support has kept financial aid high, especially at private schools. But the recession is shifting the burden for financing a college education from the provider, the government, to the user, the students and their parents. Inevitably, tuition will rise, financial aid will fall, and the coincidence of the two will clearly threaten access to higher education - especially for the middle-income student.

Student access The problem of access for students is perhaps more critical than the problems faculty face; certainly the effect are already being felt. (Even faculty rank financial aid as the No. 2 issue in higher education today, right behind compensation.) Because of the high unemployment rate, enrollment had already expanded and the demand for financial aid had exploded before the Reagan Administration first talked about cutting Pell Grants and Guaranteed Student Loans. The effect of a tuition increase coupled with a financial aid decrease is now a foregone conclusion among students, faculty and legislators, who agree there is no way the state can offset the federal cuts. "We want to make higher education as accessible as we can," says Jerry Cook, president of the four-year-old 14/January 1982/Illinois Issues we can with the resources available. "One of the short-term achievements — and I'm not responsible for it; it began during Jim Furman's tenure as executive director — is working with the public and private institutions . . . trying to bring the higher education community together to address public policy issues." Wagner is obviously pleased to say that "what criticism there has been has been relatively softly stated. I think the institutions frequently wish we were more aggressive an advocate for higher education. I would imagine that there are those in the General Assembly and in the general population who wish we were more aggressive advocates for the taxpayer or the state. We're in a real challenging and difficult position. That's what makes it exciting." What led Wagner to his position of preeminence in Illinois' system of systems of higher education at the age of 43? He describes it as a "coalescence" of his interests in government and politics and higher education and public policy. Wagner grew up in a working-class family in Chenoa; his father, now retired, was a crane operator in a stone quarry, his mother kept house. It was "assumed" Wagner would get a college education and enter one of the professions. His interest in higher education developed during his undergraduate days at Bradley University in Peoria, where he became involved in student government and where he remembers Harold Rhodes, then president of the university, as a man he "respected greatly, admired greatly." Wagner holds a bachelor's degree in psychology from Bradley, a master's in public affairs and a doctorate in public administration and higher education from the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs of the University of Pittsburgh. He joined the staff of the Illinois Board of Higher Education in 1969; he was named to replace James Furman as executive director in 1980. When Wagner wants to get as far away from the significant public policy questions of higher education as he can, he goes to soccer games and tennis matches with his children. Wagner and his wife, Judy, are the parents of four children: one in college, one a sophomore in high school, and two in the eighth grade. Is college a must in this Wagner household? "There are many people who have not chosen to go to college who are growing and responsible and productive people — probably a hell of a lot more so than some who have been to college. So I don't necessarily think that college is the answer for everyone." Illinois Student Association, which represents students at seven of the 10 state universities. "The Illinois General Assembly must define who it is they . want to be educated," he says. "If they make an arbitrary decision, they may be excluding some people they really don't want to exclude." Keane agrees with Cook that "the funding system we've set up serves the very rich and the very poor" to the exclusion of those with middle incomes. In the early 1970s IBHE policy was that tuition should equal one-third of instructional costs, that is, all university costs except those directly attributable to research and public service. The governing boards raised tuition, but the average never reached one-third. In the late 1970s, the IBHE policy was that tuition should rise with inflation. The governing boards again raised tuition; the average now stands at about one-fourth of instructional costs. But the IBHE's tuition policy is part of the state's overall income policy that generally reflects the shifting of the burden from the provider to the user. This policy suggests that because state support kept tuition at public universities low, students can afford to pay more. During the last decade, tuition, as a source of state university and community college income, doubled, growing from about 6 percent in fiscal 1971 to about 12 percent in fiscal 1981, according to the IBHE. Students at state universities say tuition increases wouldn't be such an issue if it weren't for the drop in financial aid. But Cook says the issue remains whether students can afford to pay more tuition during a recession, especially middle-income students who stand to lose the most in financial aid. "Every time you raise anything a dollar, you push somebody off the back of the boat," Cook says. "The potential is there. Whether that really happens or not is another question, but the potential is there." Some legislators like McGrew and Rep. Bob Kustra, a Glenview Republican who is also considered somewhat of an authority, since he has taught at state universities, community colleges and private schools, support the state's pay-more-of-your-own-way policy, arguing that higher education was never designed to be a bargain in the first place. "But I don't feel we should raise tuition at all in bad [economic] times," Rep. Keane counters. "That's an insane kind of proposal. You don't raise tuition when people are going to school because they can't find jobs." Tuition is very much the issue at community colleges since students there generally do not receive much financial aid, according to Dave Viar, executive director of the Illinois Community College Trustees Association, the major lobby. The recession has dashed any hopes of more federal, state or local aid, and community colleges have no choice but to raise tuition, according to Viar, The state's community college system was created in the mid-1960s as a low-cost alternative to state universities. But in the 1980s tuition has reached one-fifth of instructional costs. Normally, Viar says, students facing a tuition hike at a state university would opt for a community college. But this time, because of the pay-more-of-your-own-way policy, tuition will be nearly as high at the community college. As a result, community colleges could drive themselves right out of the higher education market, Viar warns. "Our share of Illinois State Scholarship Commission [ISSC] money is miniscule," Viar says. "If we raise tuition, our students will not get the extra money from the ISSC." The situation is worse at private schools, which have always depended on tuition to operate and where many students, especially middle-income students, have come to depend on financial aid to pay tuition. Tuition now stands at about 70 percent of instructional costs, according to Alban Weber, president of the Federation of Independent Illinois Colleges and Universities. Raising tuition at private schools at the same time financial aid is falling is doubly risky at private schools since the effect is usually an immediate drop in enrollment. "About 10 of our smaller private schools closed their doors during the 1970s," Weber says. "A couple of our larger ones have had to clip their wings. Six or seven others are having financial problems." State government got into the financial aid business in the late 1950s, creating the Illinois State Scholarship Commission and the biggest of its programs, the need-based Monetary Awards, designed to provide access — and choice — by setting the maximum grant at 100 percent of tuition and fees at public schools, and 65 percent at private schools. The federal government created the Guaranteed Student Loan Program in the mid 1960s, designed to expand access for middle-income students, especially those at private schools, by limiting eligibility to those from families who earned less than $25,000 a year. But most of the federal money came in the early 1970s with the creation of the biggest of the federal need-based programs, the Basic January 1982/Illinois Issues/15 Educational Opportunity Grants, now known as Pell Grams, designed to provide access for the poor by limiting eligibility to those whose families earned less than $15,000 a year. Then in 1978, Congress passed the Middle Income Student Assistance Act, liberalizing financial aid: the income ceiling on the Pell Grants was bumped up from $15,000 to $25,000; that on Guaranteed Student Loans was blown off. As a result, financial aid increased by a larger percentage during the 1970s than college costs increased, according to the IBHE. Even more significant, federal financial aid outstripped state financial aid by the 1980s. In terms of actual dollars, state Monetary Awards, which totalled $26 million in fiscal 1970, more than tripled between fiscal 1970 and fiscal 1980, reaching $83.5 million. By fiscal 1980, however, Pell Grants in Illinois had soared to $90.8 million. And by then the recession had struck and the demand for financial aid had exploded. In academic 1980-81, Illinois was ranked third in the nation in terms of state financial aid, by the National Association of State Scholarship and Grant Programs, according to Larry Matejka, executive director of the Illinois State Scholarship Commission, who calls Illinois' Monetary Awards a "model" program. But even a model is no match for a recession. When the governor vetoed a $5.3 million supplemental appropriation early in 1981, the ISSC was forced to ask 20,000 students who had already received fall-spring Monetary Awards for 1980-81 to cough up $100 of their tuition and fees. And the ISSC had to turn away another 14,000 students who were eligible for spring-only Monetary Awards. For academic 1980-81, the ISSC stopped taking fall-spring applications in August; the ISSC moved the deadline up to June for academic 1981-82. Congress had already put the income ceiling back on Guaranteed Student Loans, effective in the fall of 1981. No one knows how deep the federal cuts in financial aid will be when they take effect next fall, but students, faculty and legislators fully expect Pell Grants and guaranteed loans will fall to pre-1978 levels, or even lower considering inflation. Wagner admits there will be "considerable pressure" to offset the federal cuts, but argues that the state will be powerless to stop them. Matejka agrees. "I'd like to be able to ask the state to pick up the difference, but there's no way," he says. "It's a non-issue because the money isn't there." Matejka says the ISSC needs another $30-35 million just to keep pace with applications for this year. "Part of the problem," he says, "is that people have always perceived us as an entitlement program; we're not." That means the General Assembly is not required to appropriate enough state aid to fund grants for all those eligible. Matejka sees only one possible solution: earmark a part of the inevitable tuition increases at state universities to fund extra Monetary Awards for students at state universities.

"We're going to try to get the money to the students who need it the most and still achieve the goals of access and choice," he says. Trying to achieve those goals according to Matejka, is "like walking a tightrope and having two strong men pulling on each side. It gets kind of schizophrenic at times." Cook says the access crisis will be even more acute when the federal cuts take effect next fall — only one of the two strong men will win. Cook argues that Illinois will be able to maintain access to higher education for middle-income students but not access to the costlier private institutions. Private college policy That, of course, raises the issues of whether public taxes should support private schools, whether private schools should be allowed to compete with state universities and, ultimately, whether higher education should be a part of the free enterprise system. Until now, public policy has said they should. Financial aid to private schools is designed to offset public tax support of state universities. When tuition is raised at state universities, financial aid is raised for students at private schools. "Every time the maximum [Monetary Award] goes up, it puts more money into the private schools," Cook says. "Two-thirds of the money goes to one-third of the students. That seems incredible. You can send two students to a state university for the price of one at a private school. You can almost send three for the price of one." "He's got a point if you're talking strictly in terms of dollars," Matejka concedes. But in terms of awards, far more go to students at state univer-sities. And in terms of value, 100 per-cent of tuition and fees are covered at state universities. Increases in the maximum Monetary Award are tied to the increases in state university tuition. The increases are far smaller than those at private schools, argues Karol Dendor, acting chairper-son of the Federation of Independent Illinois Colleges and Universities Stu-dent Advisory Council (FIICU-SAC), the major lobby for students at private colleges. As a result, the maximum Monetary Award now covers only about 50 percent of tuition and fees at private schools, not the 65 percent was designed to cover. Dendor says students at private schools are more worried about the cuts in the federal Pell Grants and Guaranteed Student Loans than the are about the lack of state support for the state Monetary Awards. Weber ex-pects the federal cuts to "hit private schools in the solar plexus." The body blow won't be felt until next fall, but he says the "atmosphere of uncertain-ty" surrounding the cuts has already taken its toll: students no longer feel they have a choice. "You can already see it occurring," Dendor says. "Students are going directly to state universities because there's no money [for financial aid] at private schools." Friedman agrees with Cook that the crisis will force Illinois to choose between access and choice. "And you know where the choice is going to fall," she says, "on the access side." That choice and access to higher edu-cation, as Illinois has enjoyed it, will not survive, seems all but certain. Whether the quality of higher educa-tion, as Illinois has known it, will be maintained, remains to be seen. But clearly the fiscal crisis will force the question. As always, The Bard has summed up the situation: "He that wants money, means, and content is without three good friends" (As you Like It). 16/January 1982/Illinois Issues |

|

|