|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Illinois trial judges: pragmatic fact finders By STEPHEN DANIELS, REBECCA WILKIN and JAMES BOWERS Although Illinois trial judges handle over three million cases a year, involving tens of millions of dollars, the public's general perception of them is based largely on fragmentary information and splashy accounts of sensational trials. The folio wing article, based on an extensive survey of state trial judges conducted by Sangamon State University's Center for Legal Studies, presents a clear picture of these judges, their backgrounds, their work and the way they see themselves JUDICIAL REFORM has been a perennial issue in Illinois and elsewhere for a century. Without it, many good government groups and professional organizations might well disappear for lack of a sufficient evil with which to do battle. There has been considerable and often heated debate over the problems of the courts and their proper function or role in U.S. society. Most reform efforts have been aimed at the foundation of the judicial system — its trial courts and trial judges. Yet it is ironic that with all of the talk and effort about reform, we still know surprisingly little about trial courts and judges in Illinois and what exartly is "out there," especially beyond Cook County. As court researcher John Paul Ryan and his collaborators put it, our views of the lowest parts of the system ". . . are a curious mixture of fictions and half-truths." We either think that judges are too political and corrupt or we fall under the spell of what the late Judge Jerome Frank characterized over 30 years ago as the "cult of the robe" — that judges are or should be ". . . oracles of an impersonal higher law. . . ." Our intention is to make a modest, tentative contribution to overcoming the lack of knowledge and understanding of Illinois trial courts and judges. We can offer nothing earth-shaking or scandalous, and we propose no reforms. Rather, we want to replace some myth, some of the "fictions and half-truths," with a bit of reality. Many of our impressions of the lowest courts are formed either by reports from critics and insiders, or by titillating glimpses behind the judicial bench in sensational coverage of "big trials." Scholars have focused primarily on the upper courts over the years, and our awareness of the lower levels has been limited. The fictions and half-truths and gaps in our knowledge of these lower courts are unfortunate because the Illinois trial courts represent an enormous investment by the state in the ordering of private, civil matters and in the enforcement of state policies. In the words of one trial judge: "The trial judge functions at the level of the legal system which is closest to ... real life situations." At the time of the survey, according to lists provided by the Illinois Court Administrator's Office, there were 654 sitting trial judges in Illinois, 371 circuit judges and 283 associate judges. They handle over three million cases a year, involving tens of millions of dollars and perhaps hundreds of thousands of people. Yet we know almost nothing about them. What are their backgrounds and what did they bring with them to the bench? What do they do? On what do they spend their time? And how do they perceive their roles or functions as trial judges? This last item is particularly important, for students of human behavior have found that in many situations the way in which people perceive their role can have a major effect on how they play that role. To address the questions we have just posed, in 1980 we conducted a mail survey of a sample of Illinois trial judges. Surveys were sent to about half of the circuit and half of the associate judges across the state. Overall, our response was 51 percent, or 159 out of a sample of 312. Of the 177 circuit judges, 55 percent responded, and of 155 associates 45 percent responded. The judges We began with the judges themselves and the backgrounds and experiences they bring to the bench. Our interest was in what the recruitment process has given the state, and eventually in what effect this has on the judiciary. Recruitment refers to the process by which judges reach the bench — their family background, their political experience, etc. It includes the selection process, but this is only the end of the process. In short, asking about recruitment means asking what kind of person becomes a judge and what difference, if any, it makes.

By looking at the averages and percentages in the responses to our survey, we can construct a portrait of the "average" trial judge in Illinois. This portrait combines the responses from both the circuit and associate judges (see table 1). The average judge in Illinois is a white male, 52 years of age. He was born in Illinois and has lived most of his life in the circuit which he serves. He came to the bench when he was in his middle-forties, and has served on the bench for a little over eight years. Politically, he is only a bit more likely to be a Republican than January 1982/Illinois Issues/17 Democrat, and he is moderate to strong in the strength of his party preference. He is likely to be middle-of-the-road to conservative in his stand on political issues. In terms of religion, he is almost as likely to be Catholic as Protestant, and if Protestant he is more likely to be either Methodist or Presbyterian. He is very unlikely to be Jewish. The survey also attempted to examine the judicial recruitment and selection process in the broadest sense, to determine what kinds of people become judges and what differences, if any, their backgrounds make. Background information on a father's occupation can be seen as at least a rough indication of social status. The fathers of the average judges could have been almost anything, though they are somewhat more likely to have worked in professional/managerial occupations. About one-third fell into this area, which includes the legal profession. Only a bit over 10 percent of the paternal occupations were in law, and only one was a judge. Other occupations ranged from coal miner to physician, from factory worker to minister. The average judge is, of course, college-educated, and he most likely took his undergraduate degree (68 percent) as well as his law degree (75 percent) in Illinois. His undergraduate major is most likely to be in political science or one of the other social sciences, in economics or in a business-related area.

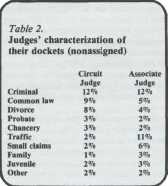

Three important things emerge from this part of our portrait of the average trial judge in Illinois. First, the present recruitment process (not only in Illinois but elsewhere) produces a trial judiciary almost exclusively white and male. Almost 98 percent of the judges responding to our survey were male, and 92 percent were white, and all female judges responding to the survey were associate judges. Second, Illinois trial judges seem to be a relatively conservative lot. Third, as studies in other states found, there is a very strong element of localism in the judges' backgrounds. Most judges are Illinois-born and educated, and have lived their lives in their circuits. We could presume, as a result, that they reflect with fidelity the values and norms of their respective communities. The survey suggests that the judges' conservatism and their identification with community values gives them a limited rather than an expansive view of what their role is on the trial bench. The average judge came to the bench directly from private practice (67 percent of all judges). A little over 10 percent came directly from an elected public office, and a little better than half of these elected officials were state's attorneys. Approximately 8 percent were assistant state's attorneys and another 6 percent were employed in some other government position. Also, about 30 percent of the judges said that they had been political officeholders at least once in their careers before coming to the bench. Because the trial judge may hear cases in many areas of law, it is worthwhile to know if they bring any particular substantive expertise to the bench, especially since fewer than half report having had any special training after reaching the bench. The average judge considered himself especially competent in at least one area (87 percent), and possibly in two areas (68 percent). The areas of special competence are most likely to be criminal, trial litigation or probate. By far, criminal is the most often listed — 28 percent listed it as their first specialty, 11 percent as their second and 4 percent as either third or fourth. Only 25 percent reported an expertise in four areas. Overall, the areas of expertise are scattered across the legal spectrum from appeals to zoning, suggesting that many judges had a relatively general practice. The methods of selecting judges have caused continuing debates about relative virtues of elections (either partisan or nonpartisan) or appointments of judges. Many states use a combination of both systems. In Illinois, circuit judges are elected on a partisan ballot, associate judges are appointed by the circuit judges of their respective circuits. The survey revealed few major differences when comparing the av-erage circuit judge to the averages for his associate counterpart. Both are white and male. Both are likely to be conservative in their stances on issues. Politically, the circuit judge is more likely to be a Democrat, and he is also a little stronger in his party preference (perhaps reflecting the partisan nature of his selection process). Both are likely (65 percent and 71 percent, respec-tively) to have come from private prac-tice. With minor differences, both come from similar social, economical and educational backgrounds. Both circuit and associate judges have lived in their respective circuits most of their lives, although a circuit judge is likely to have spent a greater proportion of his life in his circuit. Still, localism is strong when we con-sider that both are likely to have been born and educated in Illinois. In general, the method of selecting a judge in Illinois (appointed associate versus elected circuit) and the entire recruitment process has produced judges who are, on the average, more similar than dissimilar. The circuit and associate judges differ the most in areas of party preference, ideology and perhaps localism. Docket One method of exploring what a trial judge does is to examine how the judges characterize their dockets- as either confined to one legal area, or in eluding a variety of cases. About 55 percent of all judges are assigned to a particular area with the remainder hav-ing a general docket. Circuit and as-sociate judges are about equally as like-ly to be assigned, and if so the most likely assignment is criminal cases (14 percent of all judges were assigned to criminal at the time of the survey). The rest of the assignments are in widely scattered areas. We asked those judges not assigned to break down their dockets in terms of percentage of caseload in various areas. As might be expected, the nonassigned judge — both circuit and associate — handles a wide range of cases. Again, there are some small, but noticeable differences between the nonassigned circuit and associate judges (see table 2). 18/January 1982/Illinois Issues  The associate judge's docket includes a higher percentage of small claims and slightly larger percentages of family and juvenile cases. The circuit judge's docket has a larger percentage of com-mon law cases and a larger percentage of divorce cases. His docket also has slightly higher percentages of probate and chancery. The circuit judge, whether assigned or not, also reports spending a little more of his time on purely administrative matters. Two things emerge from this brief overview of how the judges describe their dockets. First, associate judges, who are a bit more likely to hear family and juvenile matters, are also a bit more likely to bring to the bench an expertise in these areas. It is also interesting that even though divorce accounts for the third largest percentage of the average circuit docket (non-assigned), it is not likely that divorce will be an area of expertise brought to the bench by a circuit judge. Second, and perhaps contrary to common assumption, judges as a whole do not spend most of their time on criminal matters. This is particularly interesting since most circuit and associate judges who bring an expertise to the bench are likely to have that expertise in criminal law. The associate judge's docket includes a higher percentage of small claims and slightly larger percentages of family and juvenile cases. The circuit judge's docket has a larger percentage of com-mon law cases and a larger percentage of divorce cases. His docket also has slightly higher percentages of probate and chancery. The circuit judge, whether assigned or not, also reports spending a little more of his time on purely administrative matters. Two things emerge from this brief overview of how the judges describe their dockets. First, associate judges, who are a bit more likely to hear family and juvenile matters, are also a bit more likely to bring to the bench an expertise in these areas. It is also interesting that even though divorce accounts for the third largest percentage of the average circuit docket (non-assigned), it is not likely that divorce will be an area of expertise brought to the bench by a circuit judge. Second, and perhaps contrary to common assumption, judges as a whole do not spend most of their time on criminal matters. This is particularly interesting since most circuit and associate judges who bring an expertise to the bench are likely to have that expertise in criminal law.

Perhaps the most interesting results of our survey came from the judges' own perceptions of their roles as trial judges. They do not simply apply the law to the facts of the situation and thereby resolve disputes, yet, neither do they see themselves as being activist and interventionist, as being involved in the "remaking" of law. Reflecting their generally moderate to conservative ideological stance, the judges see their function as a limited and pragmatic one. This pragmatic approach is seen in the average judge's idea of the differences between the trial and appellate functions and his view of the personal qualities most important to his work. The trial judge, on the one hand, is a fact finder; he is people-oriented; and he has to be spontaneous. By contrast, appellate judges are seen as having more time to decide cases and as being more law or procedure oriented. According to one judge: "The trial judge . . . shoots from the hip. . . ."Another judge made essentially the same analogy. "The chief difference . . . deals with urgency [and] immediacy — shooting from the hip, if you please." Still others characterized the difference through a battlefield analogy. "The trial judge is in the battlefield while the appellate judge is in the war station receiving the reports . . . concerning what took place in the field." Another judge put it this way: "The appellate judge is removed from the scene of battle ... the trial judge is a part of the courtroom battle." The judges' pragmatic and limited view of their role is also seen in their rankings of personal qualities felt to be most important to their work. Honesty and integrity were most likely to be rated first, followed by impartiality, common sense, and then knowledge of the law. Good government associations and the general public should be pleased by the high rating for honesty and integrity. But some might question the lesser ranking for knowledge of the law at this fundamental level of the legal system. Some might also find it at least curious, if not unfortunate, that an awareness of social problems is not really considered as an especially important trait. The judges' limited and pragmatic views were especially evident in their responses to a list of specific statements about the judicial function. Their pragmatic view is very obvious and may well be a product of the immediacy of their function in the trial January 1982/Illinois Issues/19  court — a product of the "courtroom battle." The average judge is very administratively oriented, for example. Since justice requires promptness, he wants to clean up his docket. He does not see his function as arbitrating the fundamental divisions in society, and he is ambivalent about whether courts are an appropriate forum for the disadvantaged elements in society. In short, the average judge is not an activist, not an innovator, and certainly not a social engineer. While there may be great debate and concern in some quarters over an "imperial judiciary" usurping the powers of the other branches of government, there seems little reason for concern over Illinois trial judges in this regard. court — a product of the "courtroom battle." The average judge is very administratively oriented, for example. Since justice requires promptness, he wants to clean up his docket. He does not see his function as arbitrating the fundamental divisions in society, and he is ambivalent about whether courts are an appropriate forum for the disadvantaged elements in society. In short, the average judge is not an activist, not an innovator, and certainly not a social engineer. While there may be great debate and concern in some quarters over an "imperial judiciary" usurping the powers of the other branches of government, there seems little reason for concern over Illinois trial judges in this regard.

The concern for cleaning up dockets and for promptness seems to be an overriding concern for the average judge. The problem is how to accomplish this. Even though he feels constrained by existing law and does not see himself as a lawmaker, the judge approaches the problem pragmatically and flexibly. He is not so committed to existing law that he feels it is always the best policy to mechanically apply it. He is not likely to agree that in most matters it is most important that the applicable rule be settled and applied; rather, the average judge seems to feel that common sense can be more important than strictly and mechanically applying the law in a case. He is quite likely to think of the law as a framework within which he operates, and that day-to-day decision-making demands that he exercises his own judgment and discretion. The average circuit judge may be a bit less pragmatic than the associate, however, and he is not as likely to see common sense as being more important than strictly applying the appropriate rule (38 percent v. 54 percent). Additionally, the circuit judge is slightly more likely to see courts as a forum for the disadvantaged. Often, the average judge is probably acting as a pragmatic arbitrator within what he sees as a broad but well-defined legal framework. One judge summed this up nicely: "The trial judge must sometimes look beyond the letter of the law and in so doing assess the myriad of components to enable him to do justice to all parties concerned." Overall, there appears to be little fundamental difference between judges from Dovvnstate and those from Cook and the collar counties in terms of how they view their functions. More noticeable differences emerge when considering judges as a whole and their political party, ideology, years as a judge and age. While judges from both parties share many views and values, the average Democratic judge is much more likely to see courts as an alternative forum for the disadvantaged than his Republican brethren. Similar and somewhat greater differences exist among the average liberal, moderate and conservative judges. The liberal judge feels far less constrained by existing law, and more likely to see the courts as a forum for the disadvantaged than either the moderates or conservatives. Regardless of ideological stance, there is substantial agreement about the need for discretion, and equal agreement on the importance of common sense. Judges who have been on the bench longer appear to have a broader view of their function. They tend to feel less constrained by the law, yet they find the use of common sense to be less appropriate. They are somewhat more likely to see their function as arbitrating society's fundamental and rival forces, and to see courts as an appropriate forum for the disadvantaged. Interestingly, they are not likely to see themselves as lawmakers, yet remain highly committed to discretion and cleaning up the docket. Younger and newer judges, in contrast, seem to bring with them a narrower, more limited view of the courts. Additionally, the type of work a judge does may affect his view of the judicial function. Those who are not assigned to a par-ticular legal area feel loss constrained by existing law, and those assigned to criminal appear to I eel the most con-strained. Differences also appear in regard to whether the judges feel that courts arbitrate society's fundamental and rival forces. Nonassigned judes are less likely to think so, but there is a dramatic difference when nonassigned judges are compared to those assigned to criminal. Those assigned to juvenile cases appear the least likely to accept this view of the court as arbiter of basic social conflicts. While there is little dif-ference on the idea of the court as a forum for the disadvantaged, the ex-ception seems to be those assigned to juvenile. They are far more likely to see the courts as an appropriate forum for the disadvantaged. Such difference may suggest that one of the more im-portant factors shaping a judge's view of his function will be the influence of the types of cases he hears. Perspectives Generally speaking, however, there is much more similarity among Illinois judges than dissimilarity, even when comparing judges selected in different ways. Diversity, aside from perhaps party preference and religion, is not a characteristic of Illinois' trial judi-ciary. It is characterized by a high degree of localism; a noticeable leaning toward conservatism; and, perhaps most interestingly and importantly, an unusual view of the judicial function — one limited in scope but pragmatic in practice. What differences in perspective there are concerning the judicial function may be as much the product of what specific things in-dividual judges do as of their background, party preference or ideology. It would seem that the job may mold the judge. We began by saying that we in tended to provide no reforms, but rather to begin chipping away at the "fictions and half-truths" which seem to comprise the accepted view of trial courts and judges. We would like to conclude by raising some of the implications of our effort. First, the often emotional debate in Illinois over how judges are selected may, to a degree, be beside the point. The two very different ways in which circuit and 20/January 1982/lllinois Issues associate judges are chosen produce surprisingly similar sets of judges. As a number of scholars have argued, closer examination is required of the more general process of recruitment, the process which provides the "pool" of potential judges. That recruitment process has produced a judiciary almost totally white and male, and this raises serious questions of representativeness; and at least in terms of the federal courts there has been increasing concern over female and minority representation on the bench in recent years. It would seem that a similar concern is needed in Illinois.

Within the traditional model of decisionmaking, questions of representation should not be relevant. The judge is to dispose of matters by strictly applying the law to the specific facts of the parties' situation in an almost mechanical fashion. According to legal historian J. Willard Hurst, "This job was commonly thought of as the 'trial of cases,' it centered on the courtroom drama." Discretion is to be at a minimum, if it exists at all. In a sense, the "law'' dictates a particular decision rather than the judge. This presumes, however, that what trial courts primarily do is resolve real, live disputes. But studies in Illinois and other states suggest that vast bulk of matters trial courts handle do not involve real, contested trials or matters whose outcome is uncertain. These studies show that the business of trial courts is (and has been) in reality quite routine and administrative. Contested trials are few (and always have been) for both civil and criminal matters. What we have discovered about how the judges view their functions is consistent with this portrait of trial court Business as routine and administrative, and leads to the second of our conclusions and its implications. On the whole, Illinois trial judges are pragmatists. They do not seem to accept the traditional, mechanical model of decisionmaking, interestingly, not out of any apparent commitment to "pragmatism" as a formal theory of judging, but because the job requires it. The traditional model holds that the "law" dictates a specific decision in each kind of situation. For the judges, the "law" only demarcates the boundaries for decisions, and out of necessity these boundaries must be quite broad. Discretion and common sense, within these broad boundaries, become the hallmarks of judging. This raises again the question of representativeness. If a certain degree of discretion and common sense are the hallmarks of judging, then who the judges are and what they are makes a difference. And the lack of diversity — at least in terms of gender and race — of Illinois' trial judiciary suggests that the perspectives of certain segments of society are not represented and hence may have less influence on the way in which discretion and common sense are used and to what ends. More generally, the view Illinois trial judges have of their function, coupled with the idea that most of what trial courts do is routine and administrative, suggests that we may need to rethink our views and expectations of trial courts and judges. Judgments — whether by professionals, good government groups, legislatures or the public — concerning both the performance of judges and the various plans to enhance the administration of justice depend uoon the way in which the judicial function is perceived. Unless we are preoared to rethink our views and expectations of trial courts and judges in the context of their actual behavior, we can look forward to the question of judicial reform in Illinois remaining a perennial issue. Indeed, we may even need to reconsider some of the reforms of the oast 15 to 20 years. Stephen Daniels is assistant professor of political science and public affairs at Sangamon State University, Springfield. Rebecca Wilkin holds an M.A. in legal studies from Sangamon State and is a research associate in SSU's Center for Legal Studies. James Bowers holds an M.A. in political studies from SSU and was a graduate assistant in SSU's Center for Legal Studies. This research was conducted under the auspices of SSU's Center for Legal Studies. January 1982/Illinois Issues/21

|