|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

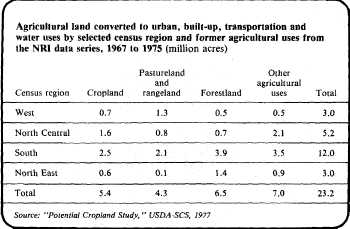

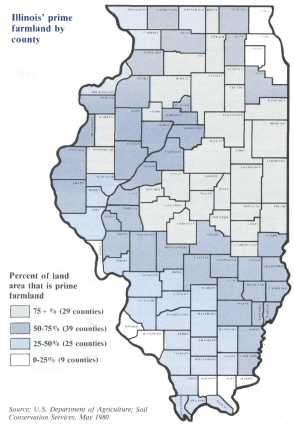

By JAMKS KROHE JR. Soil loss: the conversion factor      Photos courtesy of Illinois Department of Transportation Erosion is not the only thief robbing Illinois of its prime farmland. Every year nearly 100,000 acres of farmland are converted to shopping, centers, subdivisions, airports, highways and other nonagricultural uses. This conversion, commonly called "urban sprawl, " was once confined to areas immediately surrounding big cities. The last decade, however, has witnessed the spread of this phenomenon to rural areas. Indeed, in many parts of the state development has come to mean destruction not only of single farms but also of entire rural economies. If such trends continue, Illinois may someday import rather than export feedgrains. Both the causes and the culprits of this conversion are examined in the following article, fifth in the soil conservation series funded by The Joyce Foundation "IT WOULD be ridiculous for us to get into the same position with our farmland as we did with oil," says Ron Darden. It is part of Darden's job at the Illinois Department of Agriculture's division of natural resources to help prevent us from being ridiculous. Farmland, like oil, is a finite natural resource and, like oil, it is being wasted by Americans. Out of an estimated cropland acreage (actual and potential) of 540 million acres, roughly three million are being converted to nonfarm uses each year. What is true of the nation as a whole is true of Illinois. According to the commonly accepted estimates, the rate of conversion in Illinois is slower than the national average. But whereas only about a third of the lost acres nationwide are so-called prime farmland, prime farm acres are disappearing much faster in Illinois, if only because there are few farm acres that aren't prime. Of roughly 19.3 million Illinois acres planted in crops in recent years, 19.1 million are prime soils. Estimates vary from agency to agency, according to survey methods and definitions of "farmland." The closest thing to an official estimate comes from the U.S. Soil Conservation Service, which places the annual farmland loss in Illinois at 100,000 acres. It is a round number and easy to remember. It is also very large. At that rate, the equivalent of eight Illinois counties have been taken out of food production since World War II after have been subdivided, highwayed, a ported, shopping centered, reservoired and parked. Land use texts usually list such con-versions under the general heading "Urbanization." The automobile made it possible for cities which had been growing up to begin growing out-ward. Cities (including their immediate environs, incorporated and not, which comprise metropolitan areas) had been pulling Illinoisans out of the country-side since early in the 19th century. In the 1970s, they began spewing them back. The 1980 census revealed that nonmetropolitan areas of the state grew by 5.2 percent in the 10 years after 1970 while metropolitan areas 22/January 1982/Illinois Issues grew by only 1.2 percent — a slightly slower relative growth rate than the Midwest's but more than 2.5 times greater than that of the U.S. as a whole. This outward spread has been going on for half a century, long enough to have acquired a nickname, "urban sprawl." The desire to escape the noise, congestion, dirt, crime and high taxes of the city is hardly new. But in the 1970s this impulse to self-exile took new forms. Instead of the steady accre-tion of contiguous residential subdivisions and towns, there began to appear a new type of development whose nature is reflected in the various names attached to it: leapfrog, scattershot or buckshot development. Residential subdivisions, regional shopping malls, even industrial parks were built at considerable remove from their parent cities in rural districts, separated from them by intervening farms and usually connected to them by the umbilical of a major highway. Until fairly recently, urban sprawl was an urban life form peculiar to big-ger cities. In Illinois, sprawl — and the consequent loss of farmland — has been most pronounced in the collar counties of Chicago and the Metro East region of St. Louis. (Indeed, in DuPage County the farmer is fast be-coming a relic, the suburban equivalent of the old city rag pickers.) In the '70s, however, these centrifugal forces began to affect medium-sized cities too, and even tiny county seats have donned their own "collars" of isolated "country estates," farm equipment dealerships and mobile home parks, a trend which added "rural sprawl" to the planner's vocabulary. The causes for this flight are complex and only partly in conformity to the conventional wisdom. (Fear of crime, for example, seems insufficient to explain rural sprawl.) One factor may be the atavistic urge on the part of Americans to recreate in the typical detached suburban house, set amidst its own plot of land with pets and a small hobby garden, a miniature of the frontier homestead of 150 years ago. That such people often mistake distance for independence does not diminish the allure.

There are more prosaic reasons as well. One is financial; because rural land tends to be cheaper, taxes lower and building codes less restrictive, one can build a house in unincorporated areas of many downstate counties for $5,000 less than in the city. Another is technological. Heretofore, driving time has set an upper limit on the distance most people were willing to live from jobs (and the distance companies were willing to build from people who have those jobs). But new communications technologies have changed that. Brian J. L. Berry, Harvard professor of planning, has written of the "new scale of low-slung, far-flung metropolitan regions" made possible by the "erosion of centrality by time-space convergence." In plainer English, that means that compact cities of the 19th century type aren't necessary anymore. Changing tax laws When rural land becomes part of a city, even a distant part, its monetary value is calculated according to a different arithmetic. Farmland is cheap compared to urban land — an average acre of the very best Illinois corn land sold in 1981 for roughly $3,500, while that same acre might be worth two or three times that to a firm looking for a place to put a new factory.  Higher prices make farmland on the urban fringe more expensive to buy, of course, and more profitable to sell. They also make it more expensive to own. Illinois farmland was assessed for tax purposes at its "highest and best use" until the 1970s. In the case of land adjacent to expanding cities, this meant that farmland often was taxed as if it had condos on it rather than corn, which made farmers' arithmetic add up even more in favor of conversion. In 1972 the General Assembly authorized a dual assessment procedure, applicable chiefly to the collar counties, which made it possible to assess farmland according to its use as well as its market value. Although the medium was the tax system, the message was land use. Subsequent reforms beginning in 1977 brought all Illinois farmland under a use assessment system. But these later reforms had simple tax relief as their goal, not land use reform, and it is unclear whether or how much effect they are having on the processes of conversion. It must be said that farmers often are very willing victims of urbanization; urban sprawl in Illinois has financed its share of urban sprawl in Florida, in the form of retirement cottages. But there are factors other than greed that push farmers to abandon farming along the January 1982/Illinois Issues/23  urban periphery. The arrival of exur-banites changes more than land prices in rural areas. It unbalances the rural social and political ecology as well. urban periphery. The arrival of exur-banites changes more than land prices in rural areas. It unbalances the rural social and political ecology as well.

Strictly speaking, the problem is not that there are too many Illinoisans living in the countryside. From 1890 to 1970 the percentage of the population living in rural areas declined steadily (from 55 percent to 17 percent), but the actual number of rural Illinoisans remained surprisingly constant, at about two million. (Data for 1980 has not yet been published.) 'Subdivision people' The problem is not where people live but the way they live. Until recently, most rural dwellers were farmers. But the number of farms has declined by nearly 60 percent in the last 70 years (from 252,000 to 105,000, although changing definitions of "farm" make precise figures hard to find), with corresponding declines in rural populations. Their numbers have been replaced to an extent by the new exur-banites. But most of these urban exiles have not given up the city for the country life. Instead, they've taken the city into the country with them. A group oi DeKalb County farmers interviewed in 1980 voiced complaints that can be heard across the state about who they called "subdivision people." Farmers complained that these people do not understand the peculiar needs, of farmers. They regard farm fields as open space. They tend to drive more, so that traffic on narrow country roads increases; maintenance becomes a problem as a result, and commuters' impatience with slow-moving farm equipment causes irritation, even confrontations. The newcomers expect urban-type amenities — better roads, quicker snowplowing, more frequent police patrols, bus service for their kids — all services which must be paid for wholly or in part by higher taxes on land that belongs mostly to farmers. The list of complaints goes on: Farm equipment is vandalized. Trash is thrown into fields. New developments cut off access to fields, or disrupt drainage patterns. Fences are broken. Dogs must be put on leashes. Liability premiums go up. Livestock elicit com-plaints, even petitions. (Herb Klynstra, until recently the director of local government for the Illinois Farm Bureau, said in a 1980 speech, "People find that their dream of rural living did not include the odors of cattle, pigs or poultry wafting across the rural scene." Many farmers sell out rather than deal with constant carping by neighbors. In 1958 DuPage County marketed 4,500 head of cattle, 3,200 hogs and 33,000 chickens; said Klynstra, "I bet you would have a hard time finding livestock of any kind in DuPage County today, other than maybe riding horses.") Insecticides stink, dust from plowed fields drifts in to backyards, lights and noise from combines and grain dryers keep city workers from their sleep. Ironically many newcomers regard the farmers as the intruders, and the law tends to agree; in Illinois as elsewhere, nuisance law recognizes what the law books call "the natural process of urbanization." (Indeed, nuisance suits were such a nuisance that the Illinois Farm Bureau backed, and Gov. James R. Thompson signed, a so-called "right to farm" law, Public Act 82-509, in October which states that farms which have been in operation for at least a year cannot be declared a nuisance because of changes in the surrounding area Faced with the inconvenience and ex-pense caused by such encounters farmers increasingly find farming unattractive and eventually untenable. Role of government This process of subversion and con-quest is typically credited as the work of free market forces. But farmland conversion is just as much the result (often unintended) of deliberate governmental policy. In tne last century, Washington offered cheap land to homesteaders to encourage settle ment. The federal government con-tinued to pursue that policy, albeit by 24/January 1982/Illinois Issues  different means, well into the 1970s. Writing of federal tax and highway programs, the distinguished urbanist Robert Weaver notes, "The United States has done little . . . consciously to affect urban land use policy and practices; yet federal programs significantly accelerated urban sprawl, inefficient use of urban land, and excess conversion of farmland." In the 19th century the government sold public land at $1.25 an acre, and subsidized railroads to make it accessible to development; since the 1930s (and especially since World War II) it has | used tax-subsidized mortgages and interstate highways to accomplish much J the same end. different means, well into the 1970s. Writing of federal tax and highway programs, the distinguished urbanist Robert Weaver notes, "The United States has done little . . . consciously to affect urban land use policy and practices; yet federal programs significantly accelerated urban sprawl, inefficient use of urban land, and excess conversion of farmland." In the 19th century the government sold public land at $1.25 an acre, and subsidized railroads to make it accessible to development; since the 1930s (and especially since World War II) it has | used tax-subsidized mortgages and interstate highways to accomplish much J the same end.

Typical of the federal involvement in I rural development is the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA). A De-I pression-era agency founded to provide cheap development money to depressed rural areas, the FmHA has funded more than $90 billion in grants and loans into the American country-side, often with what the agency itself Inow admits to be unfortunate results. Speaking at a 1980 farmland preservation conference, Jon Linfield, then-director of the FmHA in Illinois, explained how good intentions lead to bad results: If we thought about it all, it was just a quarter acre that we were going to take for a decent house for a farmer's son somewhere and then once we'd done that we couldn 't very well refuse another quarter acre just across the highway. And then a developer came along and built 10 tract houses and all this was a mile away from the nearest town, and it didn't seem unreasonable . . . The wells for all those new homes went dry, residents were paying $25-$50 a month to haul water. Farmers Home with grant monies up to 50 percent extended a rural water system from that town a mile away, and then with an abundance of water, septic fields began to deteriorate. . . . The solution of course was a sewer system. Farmers Home financed that too, along with EPA. . . . When we ran our water and sewer line out there, the land [in between] became, not prime farmland, but prime development land. The first chicken shack tapped into the line, and then there was an implement dealer that needed more space, then there was 26 houses in a subdivision, next a 16-unit apartment building. We didn 't finance all of these, just some of them. Finally the ultimate arrived and they put up a McDonald's hamburger stand. . . .

All those cars led to traffic congestion and potholes, the school at the edge of town is no longer sufficient, the sheriff says he has to have another deputy patrol the area, foot traffic demands sidewalks and street lights. So much land has been paved over that they've got to have a storm sewer system now and to add insult to injury, the farmer's son that Farmers Home financed on that quarter acre six years ago, complains about all the people, sells out his father's farm to a developer and moves to Alaska. The developer . . . subdivides the remaining 80 acres into deluxe five-acre ranchettes for tired city executives who are seeking rural solitude while the surrounding farms are threatened by complaints about the noise and the odor and the owners are subjected to continual pressure to sell, just a few acres so that the cycle can commence all over again. Farmers Home is not the only villain, of course. U.S. Agriculture Secretary John Block said in a Washington speech last fall that too much of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's rural development money was going to urbanizing areas near cities rather than truly rural ones, and pledged a redirection. The Internal Revenue Service's tax code made new homes not only

Photocourtesy of Roger McCredie January 1982/Illinois Issues/25 affordable but profitable; as rising incomes pushed families into higher tax brackets, home loan interest deductions saved more and more money; the deduction saved a nickel for every dollar of interest paid by people in the 5 percent tax bracket, but saved 50 cents when the same family moved up to the 50 percent bracket. The Environmental Protection Agency underwrote sewer construction, federal highway grants made it cheap for states to build roads on which commuters could speed to and from jobs. Even the recently revised federal policy of oil price control has abetted urbanization indirectly by keeping the price of gasoline below world levels.

State and local governments didn't just stand and wave as this exodus passed by. Lax local zoning and building codes, for example, make construction in unincorporated areas attractive to developers. The fragmented nature of local government in Illinois means that its metropolitan areas, though of one piece economically and geographically, are split into several separate taxing and administrative parts. Each subdivision within the greater metropolitan area competes with its immediate neighbors for taxable development. Outlying villages and townships raid their parent city for new residents, promising less crowded schools or lower taxes. Such settlement policies usually prove shortsighted; population growth brings in new revenue, but it also brings demands for more services, which pushes up tax rates, which provides an ambitious village up the road with an argument to entice people there. Thus rural sprawl is not just a rural problem. As Clyde Forrest, a professor of planning at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has noted, "The problems that we have in rural land conversion are inseparable from 26/January1982/Illinois Issues the problems of urban development." The only local ageney whose mandate extends over an entire metropolitan area is the regional planning commission, but its role is largely advisory, and so it is reduced to the role of scold. Ted fvlikesell, director of the Southwestern Illinois Regional Planning Commission, has stated that no one could have contrived a governmental system better suited to encourage land waste than Illinois local government, which he describes as "a series of subsystems to serve the immediate demand of each special interest group" which are "uncoordinated and generally in conflict." Cost of conversion The costs of conversion are substantial. Using the 100,000-acre-per-year loss rate and 1978 data on prices and farm size, Jim Frank of the Illinois Department of Agriculture has estimated that farmland conversion costs the Illinois economy $46 million in gross sales of corn and soybeans each year, which earns about $21 million in net income for the state's grain farmers. Also lost are 719 farm jobs. Those 100,000 acres constitute roughly 373 farms, and the continuing loss of farms and farmers is eroding the economic infrastructure that sustains the rural areas. Exurbanites only partially replace the lost economic weight of the departed farmers. Subdivisions are nonproductive uses of land, and even a suburban lawn cannot consume the fertilizers and seed on which farmers — and farm businesses — depend. Frank notes, "Agriculture has a great deal of importance to the state's economy." But not as much importance as houses or highways; land will become as valuable for planting as it is for platting only when food becomes as valuable as houses — and by then it may be too late. As Frank points out, "The continued unchecked rate of conversion cannot have anything but a detrimental impact on Illinois and all of its citizens."? James Krohe Jr. is a contributing editor to Illinois Issues and associate editor of the Illinois Times in Springfield; he specializes in planning, land use and energy issues. January 1982/Illinois Issues/27

|