|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

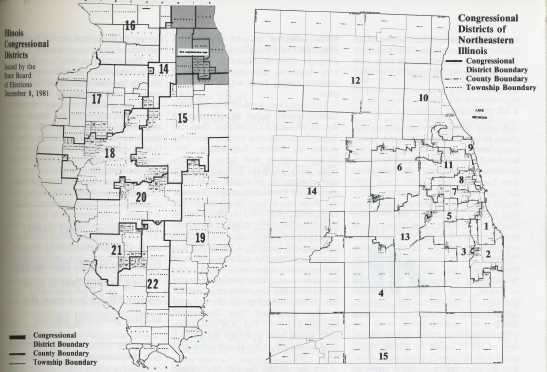

By ROBERT MACKAY The new congressional districts The nation's population has shifted to the South and West over the past 10 years. No surprise here. And Illinois will lose two seats in the U.S. Congress, which is also well-known. What is remarkable is the extent to which Illinois Democrats were able to control the remap process and minimize their losses, even though the Republicans control the governorship and half of the General Assembly. How they did it and what it will mean to the state is explored in the following article by Robert Mackay, Illinois Issues' Washington correspondent.  THE CLOUT OF Illinois in the U.S. Congress will have to be maintained with two less in the delegation. The 1980 census showed Illinois' population had not grown enough to offset gains in other states. Actually, the state started losing seats after the 1940 census and may never again reach its peak of 27 seats. Illinois' diminished delegation for the 1980s now numbers the same as it did in the 1890s. The federal order to the state to eliminate the two seats for the 1980s was simple enough. But achieving that end was hardly simple. In fact, it is becoming the norm for congressional redistricting in Illinois to get mired in political games in Springfield and to eventually wind up in the federal courts. It was no different this time, as the new congressional map was chosen by a three-judge federal court panel in Chicago and affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court. The new map — drawn by Illinois House Democratic leader Michael Madigan of Chicago, with Mayor Jane Byrne's blessing — eliminates two Republican seats by placing four GOP incumbent congressmen in just two districts. The political makeup of the delegation — now at 14 Republicans, 10 Democrats — is expected to slip, at best, to a 12-10 GOP margin. It could very well end up at 11 each. Whatever its makeup, the delegation will remain at 22 members until at least 1990, when the next census is taken. The court decision provided the Democrats with a form of revenge for the redistricting that took place a decade ago, when a different federal panel accepted a Republican map that cost the Democratic party two seats. The new map places Rep. Edward Derwinski (R., Palos Heights), a senior member of the Republican delegation, in the new 4th District with fellow GOP Rep. George O'Brien (R., Joliet). One of them will be eliminated in the March 16 primary. Within an hour of the Supreme Court's refusal to hear a Republican appeal of the map decision, O'Brien issued a statement saying: "I abhor the prospect of a primary contest with my good friend Ed Derwinski . . . but I have no choice. Most of the people I represent in the present 17th District will be in the new 4th. So I will run there and I expect to win." Derwinski praised Madigan's "diabolical cleverness" in persuading the federal judges the Democratic map was the best of three maps offered for their consideration. The plan also put Rep. John Porter (R., Evanston) of the old 10th District into the Democratic 9th District of Rep. Sidney Yates of Chicago. To avoid a near-certain loss to Yates, Porter moved his residence north to run against fellow Republic Rep. Robert McClory of Lake Bluff (the old 13th District) in the redrawn 10th District. The 74-year-old McClory — a 20-year House veteran — at first vowed to fight for reelection. But on January 13 he became the first official casualty of redistricting as he announced his retirement from Congress. McClory said he was taking the action because he did "not relish a divisive, bitter, expensive and potentially self-defeating campaign against another younger and capable Republican colleague." Although he denied harboring any bitterness, McClory — the ranking Republican on the Judiciary Committee — said he had hoped for his reelection and "the election of a Republican majority in the U.S. House this year. I even had hopes of becoming chairman of the House Judiciary Committee" — an event that would have occurred automatically if the GOP attained a majority. Porter, 46, a two-term congressman, was obviously pleased by McClory's decision, which left him with no opposition in the primary, and he said he would concentrate on the general election in November. The new map did not stop there however. Rep. John Erlenborn (R., Wheaton) was given so much new and unfamiliar territory in the new 13th District that for a while he explored the possibility of seeking reelection in another district. He said only 48 percent of the territory in the new district is from his old 14th District. He was being challenged by Republican state Sen. Mark Rhoads, who has run in "85 to 90 percent" of the new district. In the Springfield area, Rep. Paul Findley's comfortably Republican 20th District became marginal under the remap. And Rep. Dan Crane (R., Danville) lost territory favorable to him on the western end of his old 22nd District and picked up two Democratic counties, White and Hamilton. But his new district, the 19th, should remain Republican. In Southern Illinois, Rep. Paul Simon (D., Carbondale) gained about 40,000 mostly Democratic voters in an area south of East St. Louis to form the new 22nd District. The change should benefit Simon and not appreciably harm Rep. Melvin Price (D.,East St. Louis), a 36-year House veteran now in the 21st District. The Republicans lost two seats despite census figures showing a hefty loss of population from within the Democratic stronghold of Chicago and an increase of population in the GOP suburbs. How they managed to lose those seats is not a mystery to those familiar with the redistricting process and the political maneuvering that goes with it. Each party knows what is at stake — its influence in the delegation in Washington, perhaps for the entire decade — and acts accordingly. 6/April 1982/Illinois Issues

The process Most states put few or no restrictions on the drawing of congressional districts and the U.S. Supreme Court has set only two firm rules: A state must determine its "ideal district population" — the total population divided by the number of districts apportioned to the state — and then draw districts with populations as close as possible to that number; no state can draw districts with the "intention" of diluting minority voting strength. Other than that, states can do as they please. Some states have bipartisan or "nonpartisan" commissions redraw the lines. But at least 41 states, including Illinois, put final control in the hands of their state legislatures. State legislators, of course, protect and promote the interests of their party. Districts are often drawn to protect a party's incumbents, particularly veterans with friends in the state legislature. But there are other considerations. Maps sometimes are drawn to create a district from which an influential state legislator can run for Congress. But when legislators cannot agree on a map, the matter ends up in court, and that has been the case for the last two Illinois maps. The process begins as soon as the U.S. census is completed. Seats are apportioned in the U.S. House on the basis of a complex formula called the "Method of Equal Proportions," which was adopted in 1941 after being developed by a Harvard mathematician and endorsed by the National Academy of Sciences. "Priority numbers" for a state to receive a first seat, a second, and so on, are calculated by dividing the state's population by the square root of (n-1), where "n" is the number of seats for that state. The priority numbers are then lined up in order, and the seats are given to the states with priority numbers until 435 are awarded. The method is designed to make the proportional difference between the average district in any two states as small as possible. The Census Bureau figures out how many districts a state gets and sends that information to the president and the clerk of the U.S. House. The clerk then sends a certificate with each state's number of seats to the respective states for redistricting purposes. The 1980 census put the U.S. population at 226,504,825, up 11.4 percent from 1970. Altogether, 17 House seats moved from the so-called Frost Belt to the Sunbelt states in the South and West. Florida gained five new districts; New York lost five. As for Illinois, its population was set at 11,418,461 — a 2.8 percent increase over 1970, but still far behind the population growth in many other states. Illinois was given 22 congressional districts, a decrease of two. Based upon its total population, the ideal population for each district would be 519,021. Among the top 25 population losers in the United States were three districts from Illinois, all from Chicago: Cardiss Collins' 7th District on the Near North and Near West sides; Harold Washington's 1st District on the South Side; and John Fary's 5th District on the Southwest Side. In fact, most of the Chicago districts lost population while the downstate districts picked up people. The suburban 12th and 14th districts each recorded more than a 30 percent increase in population since 1970. April 1982/Illinois Issues/7 The politics When it became obvious Illinois was going to lose two congressional seats, party leaders began talking about the last-hired, first-fired concept in which the newest members of the delegation who had also lost people from their districts would be eliminated. That would have been Washington and Rep. Gus Savage of the 2nd District, two blacks who are not considered members of Chicago's Democratic organization. Savage called such talk "racist" and Washington warned the three blacks on the delegation — Washington, Savage and Ms. Collins — would stick together and cause problems for the Democratic organization if it tried to dump one or more of them.

The Republicans tried to take advantage of the situation by allying themselves with Chicago's black delegation. But the ploy failed, because many of the black state senators are allied with the Cook County organization. The Republican-dominated Illinois House adopted a congressional redistricting plan put forward by House Speaker George Ryan that expanded the three black districts in Chicago, making them safe, but combining four Chicago area Democratic districts into two. Under the map, Democrats' Dan Rostenkowski of the 8th District and Frank Annunzio of the 11th were combined in a Northwest Side district and Democrats' Marty Russo of the 3rd District and Fary were combined in a Southwest Side district. The Democratic-dominated stateSenate adopted its own plan, which eliminated two Republican seats in the Chicago suburbs. However, the General Assembly adjourned on July 2 without taking final action on either plan. The case then went to a three-judge federal court panel in Chicago to decide between a Democratic map, the Republican map or a compromise map drawn by former Republican Gov. Richard Ogilvie and former Democratic Secy, of State Michael Howlett that eliminated one "safe" seat from each party. Each of the maps preserved the three black seats in Chicago. The Democratic plan filled out those underpopulated minority districts by extending their boundaries into the southern and western suburbs, a technique that tends to dilute the influence of more conservative suburban voters. The Republican map concentrated minority strength in the city, with only one urban district reaching into the suburbs. It also combined four Democratic districts into two. The GOP map probably would have provided the party a 14-8 advantage in the House delegation after 1982. On November 23, the court panel ruled 2-1 that the Democratic map best satisfied requirements for nearly equal population in districts. Although population variances in all three proposed maps were small, the variances in the Democratic plan were virtually nil. The court panel also said the Democratic map was more equitable because it tended to equalize partisan strength in the House delegation, whereas the Republican proposal would have given the GOP a clear advantage. Voting in the majority were U.S. Court of- Appeals Judge Robert Sprecher and U.S. District Court Judge Susan Getzendanner. Sprecher was nominated to the judgeship by President Richard Nixon; Ms. Getzendanner was appointed by President Jimmy Carter. In his dissent, U.S. District Court Judge Frank J. McGarr, also a Nixon appointee, objected to the Democrats' method of padding underpopulated urban districts by stretching them into the suburbs. The Republicans, led by Ryan, appealed the federal court panel's decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. It was the first redistricting case to reach the Supreme Court subsequent to the 1980 census. In the appeal, the GOP argued the federal court panel erred by: • Preferring one plan over another on the grounds that '"it best insures that the partisan makeup of the Illinois congressional delegation will be a rough approximation of the statewide political strengths of the Democratic and Republican parties.' The Ryan plaintiffs respectfully submit that a federal district court has absolutely no business deciding what is politically 'fair' or desirable. . . ."

• Giving undue weight to miniscule differences in the maximum population deviations among the districts in the various plans. • Approving a plan that "packs suburban blacks and Hispanics into minority-controlled districts dominated by the city of Chicago, thereby diluting the impact of minorities on congressional elections in the suburbs." • Failing to accord "appropriate weight to state policy and the will of the people by rejection of a plan that was the subject of extensive public discussion and approval by one house of the Illinois Legislature." The GOP noted the Democratic plan approved by the state Senate was withdrawn from consideration before the trial began, and the Madigan plan was never voted on by either house of the legislature. • Approving a plan that unnecessarily fragments the Chicago-suburban boundaries and does not respect existing political subdivisions. The extension of city-dominated districts into the suburbs, the GOP argued, would "waste the votes of suburban residents of these districts." In approving the Democratic plan, the federal court panel said that map came closest to dividing up the districts equally according to population and 8/April 1982/Illinois Issues was least likely to result in a retrogression of minority representation on the delegation. The panel noted the Democratic plan drew Chicago's 1st, 2nd and 7th districts in such a way as to provide each one with at least 65 percent minority residents. The Republican plan provided the 7th District with just over 60 percent. The court panel said the Democratic map "therefore creates the greatest likelihood of maintaining the number of districts where minority residents can elect a representative of their choice." The panel said the Democratic map best represents Illinois as a "swing" state that is split about 50-50 between the major political parties. It based that determination on the results of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees elections. Also, the panel noted the Republican plan passed the Illinois House with a bare majority of 89 votes and it did not pass the Senate. "Illinois has not expressed a policy with regard to congressional reapportionment," the court panel said. On January 11, the Supreme Court, without comment, refused to review the case. The Republican members of the delegation reacted to the Supreme Court decision in much the same way: "Disappointed, but not surprised." "First, they [Supreme Court] have a very heavy docket," said Rep. Porter. "Secondly, in order to take the case they would have had to put over the date of the primary. It looked fairly remote from the beginning." The post-mortems Rep. McClory called it a "very bad decision. It affirms a Democratic-inspired map which is very disruptive of the congressional districts in Illinois. The most unfortunate part is it's going to be with us for at least 10 years . . . and could affect the state of Illinois well into the next century. It is estimated four, five, up to seven Republicans could be adversely affected, even defeated. The map was clearly designed to disrupt and defeat Republicans. The Supreme Court failed miserably in this instance." The Democratic members said they thought the right map was chosen and the Supreme Court made the right decision. They have 10 years in which to savor their victory, and then it all starts over again. □ April 1982/Hlinois Issues/9 |