|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

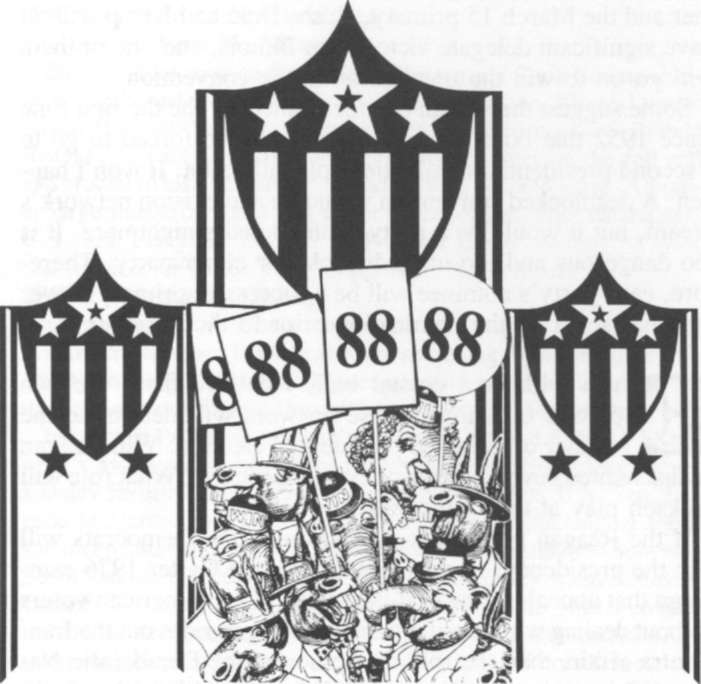

By PAUL M. GREEN Nominating the next president: What role for the party conventions?

How have Illinois Democrats and Republicans accepted the changing style of national convention politics since 1956? And what does 1988 portend for respective party leaders as they prepare for the first presidential nomination campaign since 1960 in which the incumbent will definitely not be a candidate? Underlying those questions is another: What role do party conventions play? The field of candidates is large right now and everyone is speculating on who will be nominated at next summer's conventions. To many political scientists and historians these conventions are no longer deliberative forums for party loyalists but ratifying showcases for party amateurs. Not since 1952 has either party needed a second ballot at the convention to nominate its presidential candidate. Yet critics of national conventions miss a crucial point when they downplay the value of these party gatherings. Though their scope and function may have been altered, their impact on presidential politics has not. Except for the 1960 presidential race, a comparison of each party's rival national conventions since 1956 reveals that the public perception of these four-day meetings becomes a key predictor as to who will win the White House. (See sidebar, "National party conventions, Illinois' role, 1956-1984," on pp. 18-20.) In other words, the party that is better able to hide its political and philosophical divisions at its convention will have its presidential nominee win in November. Since 1952, the power of TV and party reform has turned traditional rough-and-tumble American-style party convention politics into bad politics. Television has made the national convention a free advertisement for the party and its candidates. Disagreements are now avoided at all costs. Party leaders attempt to demonstrate unity — even if it hurts. At the same time, party reforms have changed the conventions. By opening up the convention nominating process, more delegates are selected through a primary system than through the more controlled methods of local and state party caucuses or conventions. In 1968 both parties selected a little over one-third of their delegates by primary; in 1984 that figure reached three-fourths. These delegates are often not party pros open to compromise but rather individuals dedicated to a single presidential candidate. Admittedly this change in the make-up of national convention delegates has been obscured by the fact that since the reforms the presidential nomination has been locked up by the delegate selection process before the convention begins. In Illinois, presidential primaries have always been nothing more than beauty contests for the candidates. More important is the election of convention delegates by the party primary. (Besides the delegates elected by congressional districts, there are always a set number of designated at-large delegate slots allotted for party dignitaries.) Until very recently, little hoopla or excitement surrounded either the presidential primary or the delegate races in Illinois. Both parties' convention contingents from Illinois were heavily influenced by party leaders, and it was to these individuals that aspiring candidates made their strongest political appeals. 16/August & September 1987/Illinois Issues That has all changed, and Illinois' primary has become pivotal in the election of delegates pledged to presidential candidates. The chronological order and geographical location of state primaries and caucuses that select delegates will be critical in determining the eventual nominees of both parties in 1988. Much has been written about "front loading" the nomination process (holding primaries and caucuses early in the year) and the March 8 "Super Tuesday" when approximately one-third of all delegates will be elected (most of Super Tuesday's action will occur in the South). Professors, pundits, journalists and various campaign spokesmen all have slightly different opinions as to which candidates the selection scenario favors. One area of general agreement is that unless a candidate enters the race early, only a deadlocked convention offers any hope of winning the nomination. The presidential primary timetable precludes an active candidate skipping the early primaries to concentrate on the later ones and then sweeping to the nomination with a late rush of victories. The Illinois primaries will be the political playoffs of the 1988 season. They will be held on March 15, one week after Super Tuesday. It's almost a certainty that several candidates in both parties will drop out following Super Tuesday. Thus, the key early strategy for all contenders is to stay alive until Illinois. How will Illinois fit into the Democratic picture in the primary and at the convention? Given the list of potential candidates (see box) it appears at this writing in late-July that after Super Tuesday, Dukakis, Gephardt, Jackson and Simon will make the "final four" and head to Illinois. If this scenario holds, Simon should swamp his opposition in his home state and win a vast majority of Illinois' 187 convention votes. His designated delegate candidates will carry 16 to 19 congressional districts. Jackson should win the three black districts (1st, 2nd and 7th). Only Dukakis presents a challenge to Simon elsewhere in the state — especially in the heavily ethnic districts (5th, 8th and 11th). Simon will also clean up in the selection of Illinois delegates from the so-called special delegate categories: at large, elected officials and members of the Democratic National Committee. All in all, Simon should walk away from Illinois with between 145 and 155 delegates. Obviously, political prediction is a risky business, and there are as many different scenarios as there are political observers. The most intriguing corollary to my forecast comes from a well-known Chicago political consultant (who wishes to remain anonymous) who believes that there is a strong possibility that Mayor Washington will endorse Simon and not Jackson, campaign heavily with Simon in the South and in the tradition of Mayor Daley, become a kingmaker in Atlanta. Whatever the scenario, the eventual Democratic nominee will come from the final four: Dukakis, Gephardt, Jackson or Simon. By the time Democrats gather at their national convention in Atlanta, it's likely the party will be facing problems similar to the ones they dealt with in San Francisco in 1984. Race, reform and reconciliation will vie for top honors as party leaders attempt to move the Democratic party closer to the political center  It will not be easy. Jackson's candidacy, the disproportionate involvement of the liberal left in Democratic primary politics and the various single-issue groups will most likely make up a sizable chunk of the delegate total. Republicans planning to convene in New Orleans next summer are facing one critical political uncertainty: What will be the national status and standing of President Reagan and how will they deal with him? In Dallas in 1984, Reagan was viewed as a political god; all Republican delegates worshipped his name and his so-called revolution. It was a contest among convention speakers as to who believed in him the most. A discredited Reagan in 1988 will either force the party and its presidential candidate to blame Reagan's political opponents and the media for crucifying him unfairly or to ignore him and engage in a blitz against the Democrats and their nominee. Obviously a strong and popular President Reagan would give 1988 GOP presidential strategists a far easier political path to the White House. Illinois Republicans will have 92 delegates at the convention. Prior to the Iran/Contra hearings, political forecasters were predicting that the GOP delegate races in the March 15 primary would follow the 1976 pattern: Bush, like Ford, would sew up the Republican establishment. Furthermore, they predicted that Bush would cloak himself in Reagan's mantle without going overboard, would take some lumps from rightwing supporters of Kemp, and would end up winning a solid, if not spectacular, percentage of the delegates. Given recent events, Bush's campaign has metamorphosed from the larva to the pupa stage: It's in a coma and not going anywhere. The vice president still has considerable support in Illinois, but he is no longer the Prince of Wales. The result? Dole now becomes a major alternative for Illinois Republicans fearful of moving the party too far to the right. August & September 1987/Illinois Issues/17 Unless there is a surprising development between this summer and the March 15 primary, Bush, Dole and Kemp will all have significant delegate victories in Illinois, and one of them will go on to win the nomination at the convention. Some suggest there is an outside chance for the the first time since 1952 that both political parties may be forced to go to a second presidential nomination roll call ballot. It won't happen. A deadlocked convention would be a television network's dream, but it would be a party professional's nightmare. It is too dangerous and too unpredictable for either party. Therefore, each party's nominee will be a successful primary player who has sewn up the nomination prior to the convention. Even without a crystal ball, I believe there are two pivotal questions whose answers will determine the winner of the 1988 presidential election: Will Reagan be discredited beyond repair or even impeached? What role will Jackson play at the Democratic convention? If the Reagan presidency is destroyed, the Democrats will win the presidency. It would be a modified Carter 1976 campaign that appeals to the best intentions of the American voters without dealing with specific issues. If Reagan rides out the Iran/Contra affair, then the role of Jackson at the Democratic National Convention becomes critical. It seems likely that Jackson will come to Atlanta with a sizable bloc of delegates. Some private polls suggest that if the Democratic presidential field remains large, Jackson may lead most of the primary season in the delegate count. However, Jackson cannot win the Democratic nomination or the presidency in 1988. But if Democratic party leaders, to appease Jackson, move the convention's platform far to the left or select him as a vice presidential candidate, the Republican nominee will sweep the country except for the District of Columbia's three electoral votes. Of course if Reagan's presidency remains strong and Democrats do not woo Jackson, then any combination of potential tickets in both parties suggests that 1988 will be a close election with the Republicans listed as the favorites. Why? Unless the Democrats can win electoral votes west of the Mississippi River and south of the Mason-Dixon line, they will never regain the White House. What does it all mean? Recent presidential politics reveals that both parties are products of their past. The Democrats, like the rest of the country, have been unable to come to grips with the race issue, and due to the Vietnam War and the 1968 convention, they have been unable to focus on a foreign policy acceptable to a majority of voters. The Republicans, starting with the Goldwater 1964 convention, have lurched and lunged to the right. Today, it would seem impossible for the Republican party to consider a liberal Republican, like Nelson Rockefeller, as its presidential nominee. Of the two parties, the Republicans have matched the mood of the American electorate far better than the Democrats. Paul M. Green, director of the Institute at Governors State University, is coauthor with Melvin G. Holli of The Mayors: The Chicago Political Tradition, Southern Illinois University Press (1987). Green is a contributing editor to Illinois Issues and writes regularly on politics and elections. 18/August & September 1987/Illinois Issues

20/August & September 1987/Illinois Issues |

|

|