|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Illinois toll highways: Will they ever be freeways? This is the second of two articles on the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority. The first appeared in March.  On a clear day you can easily see Chicago's skyscrapers from a rooftop in Itasca or Elk Grove Village, two suburbs side by side a few miles west of O'Hare International Airport. The drive downtown from either suburb, once you get around O'Hare, is almost a straight shot. For commuters in Itasca the shortest route is via I-290 south of the airport to the Eisenhower Expressway. People in Elk Grove Village usually head north of O'Hare on the Northwest Tollway to the Kennedy Expressway. For both Itasca and Elk Grove Village commuters, the heavy traffic of rush hours is a fact of life. But the Elk Grove Village commuters must cope with an irritant their Itasca neighbors avoid: the 40-cent toll at the eastern terminus of the Northwest Tollway. The toll amounts to pocket change for most people. Still, it annoys them far out of proportion to nickels and dimes. Toll lanes create frustrating bottlenecks that at their worst take 20 30 minutes to get through; delays in bad weather are even longer. Furthermore, because some routes to the city are tollways and others are freeways, and because Chicagoans and downstaters don't have to put up with tollways, even the 40-cent strikes many motorists as highway robbery. To be sure, they have to concede that Illinois tollways are typically in superior condition to other thoroughfares. The pavement is smoother, and the lanes are wider. District 15 state police, who patrol the tollways only, enjoy a good reputation, and they are more visible than their counterparts on downstate Highways or Chicago's expressways. In winter, tollways are usually clear of ice and snow before municipal crews can plow suburban streets. "It isn't as if they're not getting anything for their money," says Thomas H. Morsch Jr., executive director of the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority. "We have the safest highways in the nation." Supporters of the tollway system contend that motorists who take advantage of this convenience and safety ought to be the ones who pay for it. They say it's unfair and politically unrealistic to impose the cost of three-lane expressways on people in Chicago and downstate who rarely, if ever, drive them. "The retired couple in Oswego shouldn't have to pay for a superhighway they never use," says Arthur W. Philip of Oak Brook, a member of the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority's board of directors. "Truckers and commuters should pay." Debate over the equity and efficiency of tollways has simmered for more than 35 years, ever since 1953 when Gov. William G. Stratton persuaded the Illinois General Assembly to authorize their construction. In recent years, however, the context of the debate has changed, as tollways have evolved from a temporary fix to a permanent fixture of Illinois transportation, and as their traffic has changed from primarily interstate to overwhelmingly metropolitan commuting. Stratton, along with the system's other backers, promised Illinoisans the tolls would remain in place only long enough to pay off the bonds that financed construction of the Tri-State around Chicago, the Northwest to Rockford and South Beloit, and the East-West to Aurora. "Our idea was, at the end of 40 years, when the bonds were paid off, then the tolls would come off,"says Stratton, now 75. A healthy skepticism might have served everyone well at the time; only one toll road in the United States, from Boulder to Denver, has ever had its tolls removed. But if anything the tollway officialdom was giddy with optimism. Shortly after the tollways opened to traffic, their heavy use invited predictions of early retirement of the tolls. As recently as 1966, the Illinois Blue Book quoted tollway officials as boldly forecasting abolition of the tollway authority (at the time, the Illinois State Toll Highway Commission) April 1989 | Illinois Issues | 9 and conversion of the tollways to freeways no later than 1980. If they ever believed those rosy predictions, tollway critics are now growing doubtful they will see a day when tolls come off. More and more their earnest objections sound like the pouts of adolescents who cannot accept unpleasant reality. Over the last decade or so the tollway authority has taken on a sense of permanence in the Illinois bureaucratic firmament that Stratton and the system's other political sponsors never openly intended or conceded. Barring a dramatic turnabout in policy, it seems almost certain that Illinois motorists will be paying tolls long after the maturity of bonds that financed construction of the existing highways — and conceivably as far into the future as policymakers can see. "A lot depends on the future, but the tolls won't come off if you keep on adding to the system," says Stratton. The bonded indebtedness of the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority now extends to January 1, 2009, and political pressure is indeed building to authorize the design and construction of new tollways. Specifically, municipal officials and state legislators have called variously for:

In addition, Democrats have put forward half-serious, half-facetious suggestions for the tollway authority to take over and impose tolls on I-290 (doing so would require federal legislation) and to buy the financially troubled 7.75-mile Skyway from the city of Chicago. And finally, a federally financed cost-benefit study, due out by year's end, is under way to examine the feasibility of building a tollway from Kansas City to Chicago via Peoria. If any one of these proposals came to reality, the bonds to finance the construction or acquisition would have the effect of perpetuating the tollway authority considerably beyond 2009. The possibility that any new toll road would be self-amortizing is nonexistent. "It's a tollway system," says Morsch. "It operates as a system, as an integrated system. According to the indentures, we cannot remove tolls for any one section while leaving them on another

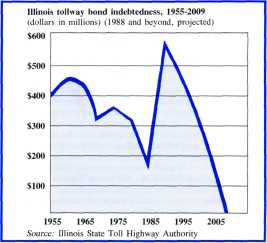

While cautioning that no new toll roads are on the horizon just yet, Morsch declares that if the legislature were to authorize a new tollway, the bonds for its construction would doubtless mature later than 2009. "Certainly from a financial perspective you'd want to issue longer than 20-year bonds," he says. The arithmetic is elementary; 30-year bonds floated in 1991 would mature in 2021, and 40-year bonds in 2031, thereby extending the tollway authority well into the next century. Contrary to widespread impression, however, the bonds financing the new DuPage Tollway have not extended the authority's existence, for they are due to mature at or before the date other presently outstanding bonds mature. The DuPage Tollway is tapping into the revenue stream of the other toll roads, though. Its $1 toll will generate enough funds to pay for only about 75 percent of its construction and operation, tollway officials predict. Also contrary to widespread impression, the East-West Tollway's reported need for $1 billion in improvements is actually without foundation. Morsch says a Chicago newspaper reporter misunderstood a casual remark about the cost, and the authority actually has no intention of spending anything remotely close to $1 billion on that stretch of road. More likely is an annual expenditure of roughly $5 million to $7 million. On the other hand, the authority is facing the need to widen and improve both the Tri-State (between I-55 and Touhy Avenue, at a cost of $250 million) and the Northwest (from the Kennedy out to Route 53, at a cost of $140 million to $150 million). And although Morsch expects these projects to be financed by tolls, he doesn't rule out going hat in hand to Wall Street, in which case the new bonds would come due later than 2009. In any case, the tollway authority appears to be here to stay, certainly well beyond its initially intended tenure. What allowed an ostensibly temporary entity to sink its roots so deep? On the surface two closely related developments were key. One, the 1968 legislation that converted the tollway commission into an authority shored up its political dependence by expanding its board of directors from three to 11 members, all of whom are appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate. About the same time, the General Assembly authorized construction of the East-West Tollway from Aurora to Rock Falls. Construction of that 69-mile extension required additional bonding, which the tollway authority issued with a final maturity date more than a decade beyond the latest redemption of any prior bonding and fully 30 years past the date by which the authority itself had predicted a few years earlier it would go out of business. Ever since then, talk of the demise of tolls has grown fainter and fainter. Of course, even if the authority were disposed to go out of April 1989 | Illinois Issues | 10 bussiness and turn over the highways to another entity, it would need to find an eager suitor. The most likely prospect, the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT), is anything but keen about absorbing the system, and, presumably, neither are counties through which the toll roads run. To do so would mean assuming responsibility for the maintenance of all or part of 1,175 miles of pavement and nearly 10,000 acres of right-of-way area. And because the tolls would be off, the funding would have to come from somewhere else. (There is precedent, as a recent Transportation Research Board study bears out, in other states for using gasoline tax revenue for the partial support of toll roads.) There is also scattered precedent for conversion of toll facilities to IDOT's control. A case in point is the Martin Luther King bridge at East St. Louis. The state agency's policy is to require full amortization of construction bonds prior to takeover. lDOT Secretary Gregory W. Baise calculates that taking over the tollway system would require boosting the motor fuel tax by at least one cent, and as much as two cents, per gallon of gasoline -- even after accounting for the savings in labor from the termination of toll collection and merger of maintenance personnel. Baise observes that the trend nationally is in the other direction: toward more user-financed enterprises. "Whoever is in my chair 15 or 20 years from now will probably have to look seriously at tolls to finance any new major construction," he says. Legislators who argue that the tollways should be free are becoming accustomed to talking themselves hoarse with nothing to show for it. State Rep. John Hallock, a Republican from Rockford, has virtually given up his fight. "There was a time when we could have" converted the tollways to freeways, says Hallock, noting that three years ago the authority's outstanding indebtedness was less than $170 million. "At that amount we could have paid it off. Now it is up to $575 million, and it is much harder," he says. Still, critics go on insisting the tollways are inequitable. One of the more interesting arguments rests on the fact that tollway users are paying twice — once by the motor fuel tax on gasoline they consume and again by the tolls they pay. For the record, as Morsch points out, courts have rejected such an argument on grounds that the use of tollways is a "matter of personal choice." And Stratton, father of the Illinois toll system, observes that tolls have held relatively stable while fares for rapid transit, buses and commuter trains have risen considerably. Nevertheless, the toll is vastly greater than the motor fuel tax. The toll averages out to 2.7 cents per mile, so that the motorist who gets 18 miles to the gallon is paying a "tax" of 48.6 cents on each gallon of gas he consumes on a tollway, far eclipsing the relatively modest state gasoline tax of 13 cents per gallon. All told, the tollway user is paying 61.6 cents a gallon, whereas other motorists are paying approximately one-fifth of that. State Sen. Bob Kustra, a Republican from Park Ridge, suggest comparing two commuters, one downstate who lives in Peoria and works at the new Mitsubishi plant in Normal, the other a suburbanite who uses a tollway to get to work. Suppose they each get 18 miles to the gallon and each drive 45 miles each way to work every day. The downstate commuter therefore pays 65 cents a day in state road-use taxes. The suburbanite, who may not be making any more than the Mitsubishi worker, pays the 65 cents in motor fuel tax on five gallons of gas plus $.80 to $1.60 in tolls, or $1.45 to $2.25. That's as much as three and a half times what the downstater pays. Further, the figure of 2.7 cents per mile represents an average that is irrelevant to suburban commuters who use the toll roads for relatively short distances. The 8,000 motorists a day who enter the Northwest Tollway at Elmhurst Road, for example, pay 40 cents each for the privilege of riding just 4.7 miles. Their effective toll is 8.5 cents per mile. Of ah the toll highways in the United States, such a rate is exceeded by only two — the Chicago Skyway and the Delaware Turnpike — according to data compiled by the American Automobile Association. Kustra also points out the anomaly of tolls on an urban belt-way. "Every other city of any size in the Midwest has free belt-ways," he says. He rattles off a list of examples: Detroit, Indianapolis, Louisville, Kansas City, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, St. Louis. The decision in 1953 to go ahead with construction of tollways cost Illinois millions of dollars in U.S. highway aid. Federal law dating back to 1916, and reaffirmed in the 1956 legislation creating the interstate highway system, has prohibited the use of federal funds for the construction of toll roads. (Subsequent legislation, passed in 1978 and 1982, permits federal funding of the 4-Rs — resurfacing, restoration, rehabilitation and reconstruction — for toll roads that are part of the interstate system, as all of Illinois' are, providing the tolls are eliminated when the outstanding debts are paid off.) The decision also forced Illinois to spend radically more than otherwise necessary on revenue collection — 15 percent for a road financed by tolls, compared with 1 percent for a highway supported by the gas tax. The final irony of the Illinois toll system's increasing foothold concerns users of the toll roads. Over the three decades since the toll roads opened, the composition of the system's traffic has undergone a profound change. In the 1950s the traffic consisted predominantly of long-haul trucking and other interstate driving — into, out of and around Chicago. Now, after years of suburban growth, roughly three of every four vehicles on the toll roads are driving to and from points within metropolitan Chicago. As a consequence, the financing for Illinois toll roads is no longer coming so much from out-of-state pockets as from commuters: from suburbanites who work in the city and from city dwellers who work in the suburbs. What once was a tax conveniently levied on 18-wheel carpetbaggers is now a tax levied on ourselves. For all the disgruntlement the system causes, though, its toll gates will in all likelihood still be bouncing up and down 20 and 30 and even 40 years from now — indeed, quite possibly an entire century after Stratton put forth his proposal. Of the two things in life that are certain, the death of a tax is not one. Thomas J. Lee is formerly political editor and editorial-page columnist of the Daily Herald in suburban Chicago. He is now pursuing a master's degree at the University of Chicago, Graduate School of Public Policy Studies. April 1989 | Illinois Issues | 11

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||