|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By ANTHONY MAN Earthquake readiness: preparing for the 'Big One' in southern Illinois

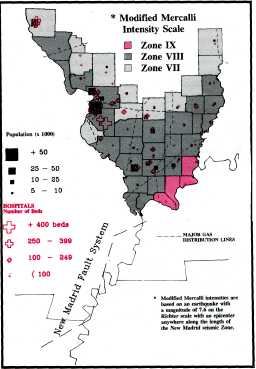

When the ground shook in California during its October 17 earthquake, the tremors reached all the way to politicians and planners in Illinois. Policymakers rushed to dust off some of their earthquake ideas and deal with an onslaught of news media questions. Politicians seized the moment to generate interest in and demonstrate concern about the possibility of earthquakes in the state's own backyard. Within 48 hours, Gov. James R. Thompson appeared before reporters in the Capitol, accompanied by a map of the central United States with multi-colored damage zones that could result from a major earthquake on the New Madrid Fault, a 120 mile long rift from Arkansas to the tip of southern Illinois. There is reason for concern. Scientists universally warn that the question is not if there will be a major quake on the New Madrid Fault, but when. And when it happens, most say it could be catastrophic. A Federal Emergency Management Agency report says a large-scale New Madrid earthquake "will produce widespread damage and losses and be among the greatest natural disasters ever known or experienced in this nation." Scientists say a major quake would reverberate much more in the soft soil of Illinois than in the more compact earth found in California. The last major earthquakes along the fault, which occurred in 1811 and 1812, produced a force estimated at 8 or higher on the Richter Scale, spreading destruction in the sparsely populated region and ringing church bells 1,000 miles away on the East Coast. Officials are eyeing the New Madrid because the danger from it is clearer than from any of the other earthquake faults running through Illinois. For example, on June 10, 1987, a moderate quake emanating from the Wabash Fault in the southeastern part of the state registered 5 on the Richter scale. It shook some people and buildings, but caused no serious problems. The oft-cited Richter scale is a measure of the energy released by an earthquake, as determined by ground motion recorded by a seismograph. Each increase of one point means the energy release is 30 times greater than the previous number. Thefore, an increase from 4 to 6 on the scale is 20 times 30, or about 900 times the energy of a 4. The California quake registered 7. The one a year ago in Soviet Armenia that caused far more death and damage was a 6.9, and state officials cite scientific predictions of a 50 percent chance of a New Madrid earthquake of 6 by the year 2000. "Those kinds of odds" are what led the governor to declare that his goal is "to make sure Illinois is prepared to respond to any earthquake activity." Toward that end, Thompson created a "task force" to determine just how ready Illinois is should a major earthquake strike. The panel has public members from almost every conceivable state agency and private sector representatives from fields such as communications, medicine and engineering. The Illinois Emergency Services and Disaster Agency (ESDA), which is already preparing for an earthquake as part of its mandate for emergency readiness, quickly geared up staff support. The committee's inaugural meeting, held the first week in November in southern Illinois, featured an appearance from Marilyn Quayle, wife of the vice president. She has made disaster December 1989 | Illinois Issues | 19

preparedness and response her special interest. The committee has an extensive mandate. It will survey the public infrastructure and examine existing emergency plans. A report and recommendations for action are due by April 1990 — in time for action in next spring's legislative session. The governor has so far steered clear of the most contentious issues, such as whether the state should impose tighter building codes, saying he wants the panel to address them. Despite the widespread predictions of death and destruction from a New Madrid quake, and the governor's publicly declared interest in the subject, it will be tough for the planners to excite the politicians who hold the power and purse strings. The California-inspired Illinois committee, and the announcement of it, is a blend of politics and substance. Thompson balanced a couple of interests. On the one hand he wished to demonstrate his administration's quick response to what will probably wind up as fleeting public interest in the subject. While at the same time he did not wish to appear, as he put it himself, as an administration staffed with "Johnny-come-latelys to this issue." He essentially conceded the problem himself: "While we do not want to panic anybody, neither do we want to risk being caught short." Talking about preparedness is easy, but action is exceedingly difficult. For one thing, there is little political advantage, and in fact some political peril in dwelling on the possibility of disaster. Also the area most in danger is one of the least populated regions of the state, and while southern Illinois is legendary for the prowess of its legislative delegation, a problem so confined may not arouse much more than curiosity on the part of politicians and the press from northern Illinois. Despite scientific assurances of the eventual certainty of an earthquake, it might not come for a while. What politician wants to talk about something that may happen well into the future, when it does not make compelling politics today? Schools are an example of the competing priorities. Unreinforced masonry buildings, which experts report would be at greatest risk, are found in educational structures. Retrofitting those buildings is expensive, although there are some low-cost protective measures, such as bracing pipes, fastening bookcases to walls, and placing film over windows to prevent them from shattering. In a period when politicians and the general public have so much trouble deciding on an appropriate level of education spending, it might be tough to explain the benefits in diverting scarce school dollars to equip schools in the southern third of the state to withstand earthquakes. Richard H. Moy, dean and provost of the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, contrasts earthquake preparedness, which he says is a real need, with school asbestos removal. "All the authorities say the best thing would be to leave it alone. A far more clear and present risk to school kids in downstate Illinois is earthquakes," Moy says. The physician has made himself conversant on earthquakes and the New Madrid Fault since he read a newspaper article about the risk some five years ago. He went to the experts, investigated the state of preparedness, and came away dissatisfied. He still feels that way and beats the drum for stepped up public attention and government action. "You could talk up a storm and politicians just don't want to hear of it," he observes. "It's just a question of priorities." Moy and others who are concerned about the threat find themselves fighting a sort of fatalism. When people hear about the potential scope of devastation — widespread fires, collapsed buildings, crumbled infrastructure accompanied by large numbers of deaths and injuries — Moy says their eyes end up looking like those of the cartoon character Little Orphan Annie. Compounding that, the critical issues — infrastructure, telecommunications and the like — are not compelling to many people. But they would be critically disrupted by a major earthquake. For example, authorities fear that the telecommunications system, which relies largely on land-based wires, would be essentially wiped out. Thomas W. Ortciger, ESDA director, predicts that vast parts of southern Illinois could be without telecommunications for 72 hours after a quake. ESDA itself relies December 1989 | Illinois Issues | 20 on land based telephone lines and is working on two solutions to the problem: a plan to rely on commercial broadcast stations for information, partially via a huge satellite dish sitting next to the emergency services agency building across the street from the Capitol, and an effort to utilize amateur radio operators to get information from the scene and decide how to deploy resources. Medical care might be almost nonexistent in southern Illinois after a major earthquake, something Ortciger calls "the Biggest issue we'll have to face." Thompson notes that "A disaster of the scale we're talking about would overwhelm even the most well equipped area," adding that "southern Illinois is less well-equipped than most." Moy warns that the current level of medical readiness means it will be impossible to take care of "badly injured people under the battlefield conditions you saw in parts of San Francisco." The impact on infrastructure, particularly the transportation system that would be vital in moving aid to a stricken area, is an unknown that will be examined by the commission. Some suggest that a severe quake might leave the Mississippi River without a bridge crossing it for 500 miles, but Gregory W. Baise, the outgoing transportation secretary and quake panel chief, says images of the partially fallen San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge are not necessarily precursors of what would happen in a New Madrid quake. He says bridges in Illinois are not built with separate spans, as was the Bay Bridge, because engineers do not want to create extra openings that would be damaged by road salt applied in the winter. Baise also says southern Illinois bridges are already subject to more rigorous standards than those in other parts of the state, but adds a caveat: "It is difficult to be able to say what a bridge can or cannot stand in a particular situation." Some highways pass over each other as do ramps at interchanges, but Baise notes southern Illinois does not have double-deck freeways of the kind seen in California. Beyond convincing people that the chances of such devastation justify marshalling for action, other political problems abound. Moy tells of briefing local officials who are anxious about luring jobs to their communities, something they see as a more immediate need. They object to anything that might scare away potential industries or force employers to spend more money on construction of their buildings. Turf is another. Stronger building codes would protect the people of southern Illinois. But state action on building codes requires investing tremendous political capital because it infringes on local officials' fiercely guarded prerogatives. Ortciger has indicated it is unlikely that the state will impose dramatic new regulations. "It's going to be people in that area making a willful decision about

The plethora of governments creates a bureaucratic problem. Unlike California, where the damage was confined to one state and one federal government administrative region, Ortciger notes that a major New Madrid quake could encompass seven states, four of the federal government's administrative regions, 128 counties, and perhaps 1,000 local governments. The state is already involved with the Central United States Earthquake Consortium, but the Interstate Disaster Compact, passed in the spring legislative session, formalized a system that would allow potentially affected states to share resources. Illinois is already developing a list of resources, and experts say the interstate cooperation could result in better deployment of equipment in an emergency. It is the very scope of an earthquake that makes it such a difficult contingency for which to prepare. "If everything were localized in one community, we could go in and handle it pretty well. If we've got the whole southern half of Illinois, especially in the metropolitan areas, we'd have our hands full," says John R. Plunk, chief of operations at ESDA. Thomas F. Zimmerman, the agency's chief of planning and analysis, likens the Illinois reaction to the California earthquake to the nation's response to the 1979 nuclear power plant accident in Pennsylvania. "Public officials are at the mercy of a public that decides the strength of these proposals," Zimmerman says. "It's a sad commentary, but it took an accident at Three Mile Island to force the nation. . . to show leadership in nuclear safety." Plunk, his operations colleague, warns that it is "impossible to prepare so that you can mitigate everything. You just cannot get to the point where you have a 7 on the Richter scale and not have damages and not have fatalities." Despite all the problems, he agrees with the governor's assessment that the Thompson administration is as prepared as possible to deal with an earthquake. "It's not going to catch us by total surprise when somebody says, 'It's happened.' We'll know what they're talking about," Plunk says. In the governor's words, the state is "prepared to deal with the emergency." The dissenters are not so sure but hope the California quake provides enough political and policy lessons to shake up a complacent Illinois system and maintain interest in the subject. Those who take a more alarmist attitude and those who are happier with the state's preparedness generally concur on one point: As far as Illinois is concerned, the California earthquake can only improve readiness.□ Anthony Man is the Springfield bureau chief for the Lee Enterprises newspapers. One of the newspapers for which he writes, The Southern Illinoisan, is in an area expected to be hard-hit by a major earthquake occurring on the New Madrid Fault. December 1989 | Illinois Issues | 21 |

|

|