And so it was that Robert Leininger, the state superintendent of education, recently visited about 40 up-and-coming

community leaders gathered at the Illinois State Library to

tell them the whole thing — schooling in Illinois — is

broken. "We aren't producing the type of product we should

be," Leininger told the Illinois Farm Leadership Alliance.

"I'm not here to defend the system. I want to change it."

Fat chance.

Leininger might more easily try to reverse the tides, or to

command the sun to rise in the west or to give the Bears a

winning season. The dynamics of change in Illinois education policymaking are every bit as immutable as the laws of

physics or the fate of Chicago sports franchises. Education

policy in Illinois is a perpetual motion machine: lots of

activity, but it never goes anywhere.

"We're not doing the Job we should

be doing," Leininger told the collection

of agriculture and agribusiness leaders.

"If you think differently, then tell me

why one of every four ninth graders will

never get a high school diploma. Tell

me why, if you're unlucky enough to go

to certain schools, eight of every 10

freshmen will never get a diploma. Tell

me why Johnny and Suzy get their high

school diplomas and still can't fill out a

job application."

• Illinois does not have an "education governor" or any other elected

official to champion the cause of kids in

school.

• Most lawmakers are motivated not

by what's right for schoolkids but

what's expedient for reelection.

• The only education special interest

with clout — that is, the ability to

influence a legislator's reelection — is the Illinois Education

Association, which has a vested interest in maintaining the

status quo.

• The education establishment is fragmented, not just in

the historic enmity between teacher unions and management groups but in the competing interests between the

different types of school districts in Illinois and the regional

conflict that divides Illinois: Chicago, the suburbs and

downstate.

|

• Bob Leininger, for all his political skill, is a toothless

tiger.

Simply put, Illinoisans are getting the educational system

they deserve.

On paper, Bob Leininger would seem to have the

perfect credentials to be the leader to bring meaningful, enduring change to public schooling in

Illinois. He's been at it — either in the schoolhouse or at the

Statehouse — for nearly four decades. He has been a

teacher, principal, district superintendent, chief lobbyist for

the State Board of Education and, since 1989, state superintendent of schools. That broad experience has enabled him

|

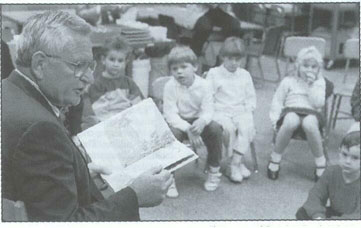

Photo courtesy of Illinois State Board of Education

Illinois school Supt. Robert Leininger as teacher

Photo courtesy of Illinois State Board of Education

Illinois school Supt. Robert Leininger as teacher

in this storytelling session

with kindergartners.

|

12/April 1993/Illinois Issues

to bridge the chasm that has long existed between those who

set policy in Springfield and those who carry it out in

classrooms throughout Illinois.

His sensitivity to the needs and concerns of teachers and

school administrators has endeared him to local educators

who have long been accustomed to regarding the state

education bureaucracy more as foe than friend. "Leininger's

appointment as state superintendent was extremely well

received by educators at the local level," says one downstate

superintendent. "Bob is viewed as somebody who really is

an advocate for schooling with the knowledge that support

has to be for the local units and not the state bureaucracy."

On the other hand, his deep understanding of the legislature

(he was the state board's chief lobbyist for 13 years under

three superintendents) and his fondness for the legislative

process, despite all its silly idiosyncracies and petty protocol, have earned him widespread respect among lawmakers.

Then again, a lot of good it's done him.

"The office is very weak," notes James Ward, a professor

of education at the University of Illinois. As state superintendent, Bob Leininger is appointed by the State Board of

Education, which in turn is named by the governor, an

arrangement hardly designed to promote bold or controversial leadership. Leininger admits that he has sometimes

gotten out in front of the board in his zeal as an advocate for

schools and that the board "reins me in."

"There is very little power," says Ward. "Bob Leininger

has tried, but by the nature of the way the office is

constructed, it's hard for a leader to come from that office."

Says Leininger: "I have some clout. But not as much as a

governor or a mayor."

"I'll share a frustration with you," says Leininger. "In

other states where there have been major movements in

education and fiscal reform — Colorado, Kentucky, Texas,

Arkansas, New Jersey — there has been an elected leader — a governor, lieutenant governor, the chairmen of the education committees in the legislature, somebody who represented the state in some capacity who stepped forward and said:

'I don't care what happens to me politically, we need to do

this.' "

Ward takes that notion one step further. "In places where

education reform has been successful, it's been the governor

who has stepped forward to make it happen. I don't know

who the last real education governor in Illinois was; maybe

Ogilvie because he passed the income tax that was devoted

to education. Education has not captured the imagination of

governors since." Notwithstanding Gov. Jim Edgar's "kids

vs. concrete" rallying cry in his March budget message,

Ward says the governor has shown little interest in the views

of educators or in cutting-edge research into the "learning

revolution" manifest in studies at universities and think

tanks at the federal level and in experimentation in some

states. Ward asserts that Edgar's modest agenda for education reform, touted recently in his State of the State address,

"flies in the face of what we know about how children

learn." Edgar's proposals for opening up the teacher ranks

to those without a teacher's certificate, for an "educational

enterprise zone" in Chicago, and other suggestions. Ward

says, "have nothing to do with public policy, but are only the

opening shots of the gubernatorial campaign."

|

Leininger: "We've had an education president and an

education governor, and I've never heard one elected official who has not said that education isn't the top priority. If

that is true, why are we in the condition we're in?"

Jim Edgar never actually promised to be the "education governor." What Edgar promised in his 1990

campaign was that education would be his top priority

and that Illinois would have "an education system second to

none." Aides contend that he fulfilled his first pledge when

"he whacked the hell out of the rest of state government so

he could spare cuts in education."

Leininger has heard all that before. Whenever elected

officials tell him that education is their No. 1 priority,

Leininger has a ready response: "I'm sure as hell glad we're

not fourth or fifth priority."

|

Ward asserts that Edgar's

modest agenda for education

reform, touted recently

in his State of the State

address, 'flies in the face

of what we know about

how children learn'

|

Even so, Leininger gives the governor credit for protecting public schools from the budget cuts that have savaged

many state agencies. "Within the parameters he's set, Jim

Edgar will show you how education is a priority," says

Leininger. "We got money when everybody else was being

cut. I'm saying that the parameters aren't wide enough. I

support a tax increase for education. Fifty-seven percent of

the people voting [on the education funding constitutional

amendment] in November support it. I think the governor

should support it. Or somebody should support it."

Not everyone, of course, agrees that the answer to the

woes of public schools lies in increasing taxes. Gov. Edgar,

for one; the General Assembly, for another. Edgar not only

has held steadfast to his vow to oppose a general tax

increase, he has this year made a crusade of imposing caps

on local property taxes throughout the state, a move that

could further restrict revenues available to schools. So

skittish have legislators been that they refused to go along

last year when Edgar proposed modest increases in cigarette and liquor taxes.

Noting the uphill struggle to get additional money for

schools, Leininger told the Farm Leadership Alliance about

the last time the state raised the income tax, back in 1989.

When he visited the office of a suburban. Republican

April 1993/Illinois Issues/13

senator, whose name he chose not to reveal, the conversation, Leininger said, went something like this:

Senator: "You want more money for kids."

Leininger: "Yes, senator, that's why I'm here."

Senator: "You want a 20 percent increase and my schools

will not get much of that, will they?"

Leininger: "No senator, they won't."

Senator: "And my constituents will pay more of that tax

increase than most others?"

Leininger: "Yes, senator, they will."

"I won't repeat the rest of the conversation," Leininger

told the farm leaders.

That senator is now part of the Republican majority that

controls the state Senate. "It will be more difficult to sell any

type of proposal that enhances revenues," says Leininger of

the Republican Senate. "The themes will be: no new taxes

and cut the bureaucracy."

'I don't see the cavalry

coming,' says Leininger,

scanning the legislative

horizon for a savior to come

riding to the rescue. 'I don't

even hear the bugle sounding'

Nor is he likely to

|

Leininger got a preview of those themes in December

when the Illinois Manufacturers' Association (IMA) unveiled its own school reform agenda. "Unfortunately," said

IMA president Greg Baise, "more money alone will not

produce the educational system desired by the business and

citizens communities." He referred to the education amendment as an "ill-conceived attempt to throw more money at a

system badly in need of reform" and said his organization

would not back additional resources for schools until the

major tenets of its reform plan were adopted. That plan,

among other things, calls for upgrading occupational education, establishing demonstration projects for school choice, increasing class sizes, lengthening the school year and

curtailing administrative costs throughout Illinois schools

"and Chicago in particular."

|

The IMA proposal was the second shoe to drop in a

widening rift between the business community and the

state's education establishment. Leininger remains bitter

over the opposition state business leaders organized to help

defeat the education amendment, rupturing what had been a

promising partnership that was instrumental in passage of a

new system of evaluating schools. The system emphasizes

holding individual schools, rather than just districts, accountable for progress in student performance. Leininger:

"They told us, 'You get accountability standards, and we'll

get you more money.' Well, I'm still looking back." He says

promises of the business community remind him of the

game he plays with his granddaughter — every time she

crawls up to the toy he sets on the floor, he moves it farther

away. "That's what the private sector is like."

The IMA's no-new-taxes reform agenda also reminded

Leininger of a story about the principal of a one-room

schoolhouse in southern Illinois.

The school board told the principal to build a new school.

"That's wonderful," the principal said.

"And we want you to use the bricks of the old school to

build the new school," the school board said.

"That's fine," said the principal, "I can do that."

"And we want you to use the old school until the new

school is done."

Leininger: "They want better education, more opportunity for kids, more equity, but they don't want to pay for it."

Well, who does? "I don't see the cavalry coming,"

says Leininger, scanning the legislative horizon

for a savior to come riding to the rescue. "I don't

even hear the bugle sounding."

Nor is he likely to.

The Task Force on School Finance, the legislature's

latest school reform vehicle, recently proposed a comprehensive plan for making the funding of schools both more

equitable and adequate. And costly. Estimates place the cost

of the plan at $1.5 billion in new taxes, a feature alone

guaranteed to ruffle the governor's coiffure. Moreover, a

quarter of the task force members wrote separate statements attacking various components of the majority report.

Also, the manufacturers' association billed its own reform

agenda as a less costly alternative to what the task force

proposed. And finally, the dynamics of legislative politics

promise the task force plan a treacherous journey.

"The easiest thing in the world to be," notes Ward of the

U of I, "is a pro-education legislator. Because no matter

what you do, some group is going to think you're great."

So fragmented is the education community — between

labor and management, between different types of school

districts, between different regions of the state — that, says

Ward, "it's easy for legislators to be passive and allow the

gridlock to continue."

Chicago, once labeled the nation's worst school district

by the U.S. secretary of education, is still the district

everyone loves to bash. So chaotic seems the leadership of

the district, so unproven remain its governance reforms, so

dreadful seems the condition of its schools that Chicago

continues to be, in Leininger's words, "the whipping boy.

We've already heard it from the new legislative leaders." So

long as Chicago suffers from its (generally unfair and

inaccurate) image of incompetence and wastefulness, it

provides a convenient cover for lawmakers and a governor

seeking to avoid increasing spending, let alone taxes, for

education.

Regional splits are exacerbated by differences among

school districts themselves. Notes Wayne Sampson, executive director of the Illinois Association of School Boards:

14/April 1993/Illinois Issues

"Elementary, high school and unit districts can't even agree

on what we need to do or should be doing." It is virtually

impossible, for instance, to change the school funding

formula without creating winners and losers — K-12

districts gain at the expense of separate elementary and high

school districts, or suburban districts pay so urban districts

can profit. Legislators don't like losers, especially when

their constituents are among them. So prevalent is legislative protectionism that there is a name for it: printout

politics. When the school aid appropriation is voted on,

most legislators want only to

see computer printouts from

the State Board of Education

showing how much money

the school districts they represent will receive. "There is

no issue we deal with that is

any more parochial than education policy," says Sen. John

W. Maitland (R-44, Bloomington) who is one of the

foremost education leaders in

the legislature. "It is a printout game for many. They care

about one thing — what the

printout says about winners

and losers in their districts

and that's how they vote."

|

If printout politics produces gridlock, special interest

politics cements it. "Another

barrier is the multitude of voices

that speak for education," notes Sampson. Though the

cacophony of disparate voices has occasionally joined in

harmony, it is more common for legislators to get separate

opinions from lobbyists from big districts, small districts,

urban districts, rural districts, business interests, school

boards, administrators, teachers and the State Board of

Education all on the same issue. The inability to speak in

unison has made it easy for legislators to play one interest

off against another. "We haven't ever learned that," says

Leininger.

Moreover, one special interest voice speaks louder

than any other, maybe louder than all the others

put together — the Illinois Education Association

(IEA). A savvy political force, the IEA has a huge campaign

bankroll, has thousands of members willing to work in

political trenches and has tens of thousands of members

who are spread throughout the state and vote. Sampson says

the IEA has experienced a couple of down years recently,

but adds, "the number of teachers, the PAC influence, the

ability to put staff in the field gives them a stronger

position." Its ability to influence the outcome of a legislative

race, even a statewide race, is legendary, as is its skill in

parlaying that political power into legislative clout.

|

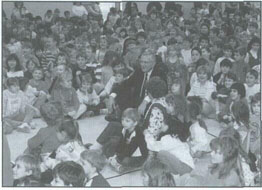

Photo courtesy of Illinois State Board of Education

Where's Bob?

Photo courtesy of Illinois State Board of Education

Where's Bob?

State school Supt. Robert Leininger

is as comfortable sitting in the midst

of these school children as he is

when lobbying for education funding.

|

That muscle is flexed, and rightfully so, for the narrow

vested interest of teachers — it is teachers who pay the dues.

But often that vested interest is in maintaining the status

quo, certainly in cases where change might endanger

teachers' jobs. Sampson wonders, for example, "Do we

really need a certified teacher in a study hall? Do we really

need phys ed for every student every day? Those requirements are protectionism for the people doing those jobs."

A few weeks ago, U.S. senators in Washington started to

get a trickle of telephone calls. Then a flood. The calls

brought a tidal wave of citizen outrage over the nomination

of Zoe Baird to be U.S. attorney general. Suddenly senators

who had been willing to wink

or look the other way about

Baird's flouting of immigration law began to scramble

for safer ground. President

Clinton was forced to look for

a new attorney general.

Hardly anybody calls

Springfield demanding that legislators

fix the schools. In fact,

Wayne Sampson ruefully

notes that public opinion

polls consistently show "people think education in the

state is terrible but their own

school is real good. It's hard

to get money for schools if

people seem happy with what

they've got."

Jim Ward: "The legislature reflects the people back home, and the people back

home are not putting much pressure on the legislature for

change. So, for the most part, we do get the schools we

deserve."

Bob Leininger spoke to some of the "people back home"

— members of the Illinois Farm Leadership Alliance — and

had another story to tell them. It was about a little girl, a

second grader, he met in a troubled urban district shortly after

he became state superintendent. When he entered a classroom, his entourage of reporters and television cameramen

urged him to kneel down next to the desk of one of the

students, Nicole as it turned out, for a nice photo opportunity.

As he knelt, Nicole began playing with a gold bracelet

that Leininger wore on his wrist.

"Where did you get this?" Nicole asked him.

"My sons gave it to me," Leininger replied.

"Do they love you?" Nicole asked.

"Yes," he replied, "they do."

"Do you love them?" she wondered.

"Yes, I do," Leininger replied.

When the entourage was ready to leave the classroom,

Leininger said, "Nicole wrapped her arms around my legs

and begged me to take her with me.

"There are a lot of Nicoles in this state," Leininger told

the farm leaders, "and we ought to be ashamed of ourselves.

And it's your job to do something about it." *

April 1993/Illinois Issues/15