|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO |

Staff |

Links |

their homes and farms, soggy survivors look for

ways to live with their unruly neighbor

When the Mississippi River swept into the city of Moline, soaking factories and rendering some homes unlivable, people there decided it was time to make a few changes. Some residents and business owners in the northwest Illinois city moved to higher ground. Earthen berms were built around large companies. A steel wall went up around the city's water plant to help keep out potentially polluting flood waters.

That was nearly 30 years ago, in 1965. It was a difficult, frustrating experience, say those who suffered through that flood. But it carried a lesson that was taken to heart.

"I like to say that forewarned is forearmed," said Moline Mayor Stanley Leach, who remembers patrolling the river's banks during the 1965 flood, shooting muskrats that were trying to burrow through hastily constructed dikes along the city's edge. "We learned a lot of lessons from that flood that helped us prepare for what happened last summer. That's not to say we weren't hurt this time. We were. But in terms of what it could have been, we were spared a lot. Not like in 1965. That was a year of lesson-learning."

All along the Mississippi and Illinois rivers, 1993 was a year of learning. The rotting fields and empty shells of homes left behind by the summer floods reminded the Midwest — the whole world, in fact — that nature is difficult if not impossible to restrict.

But a trip along the Mississippi late last year showed that the lessons learned seem as varied as the people who had to leam them. Some, like those living in the towns of Keithsburg and Valmeyer, learned their efforts to live and work near the river, seemingly protected by man-made walls of earth, weren't worth the problems wrought by flooding. They've since decided to pick up and move to higher ground. Others, like those in Meyer and Hull, learned that there are steep emotional and financial prices to pay for crops reaped from the rich soil of river floodplains. To continue farming this land they must work harder to keep water out, partly by fighting for the government to build higher levees. Still others continue to weigh the things they've learned while they decide what lessons to extract.

But one common lesson binds those affected by the summer floods: There are lots of pieces to be picked up before the water's victims can return to the lives they used to know. And while government agencies initially responded with much-needed help, there is almost universal concern and uncertainty over exactly what governments are going to do, pay for or help with in the future. They worry that one lesson of the Flood of

12/January 1994/Illinois Issues

|

|

'93 might be that their government has turned its back on them in their time of need. In Moline, as Mayor Leach pointed out, the pieces aren't as far-flung as they could have been. Some riverfront bars, restaurants and homes had to undergo fairly extensive repairs. Montgomery Elevator — an elevator and escalator manufacturer that is one of the city's larger employers — was temporarily closed by invading floodwaters. But for a city on the river, it was lucky to suffer only about $600,000 in damages, said Arden Johnson, chief of field operations in Moline's engineering department. What kept worse tragedy from striking, Leach said, was the early work the city put in as soon as flooding became a possibility. "Everybody started building dikes around everything. One company let their employees off to work on dikes. Even though we had built a wall around the water plant after the '65 flood, we sandbagged all around the wall." Again, he refers to past lessons learned. "In '65 all the factories were up against the river. Later, after they left, we built things higher, on more elevated ground. We tried to be prepared as much as possible, and it helped. In almost all cases this time, people who got flooded are staying where they are." In light of Moline's experience this summer, Leach doesn't see any drastic changes occurring in the city. "We do not intend to build a big dike along the river," Leach said. "It would knock off the view we have, and we're trying to build our riverfront up into more of a 'touristy' attraction." The biggest problem that demands a solution, said Johnson, was caused by water coming up through storm drains and flooding structures from underneath. The city now must figure out how to pay for several storm drain valves, at $60,000 each, needed to keep the river from backing up in the future into Moline's streets and on into homes and businesses. He and Leach hope federal or state aid will be available to help fund the project. But they, like many public officials, have learned that even several months after the flood, questions remain regarding which flood-related projects are eligible for public aid. Marianne Doonan, flood coordinator for the Bi-State Regional Commission serving the Quad Cities and surrounding counties, credits the state of Illinois' flood recovery efforts as far more coordinated and responsive than those she's dealt with across the river in Iowa. Overseen by Allen Grosboll, appointed chief of state relief efforts by Gov. Jim Edgar, Illinois flood aid has ranged from setting up hotlines to help farmers obtain feed for livestock to the state's Department of Transportation building temporary roads and removing tons of flood debris. |

But Doonan said she has had trouble determining which recovery projects meet which (if any) public agencies' guidelines for help. "There are [several] agencies at the state and federal levels that have gotten flood money, and they all have different eligibility requirements and

January 1994/lllinois Issues/13

different paperwork that needs to be filled out," she said. That's frustrating enough for people in a city like Moline, which now has to deal with expensive storm drain upgrades. But it's devastating to smaller towns like Keithsburg, population 747, which sits about 75 miles down river from Moline. There, dozens of families have been displaced by the flood and 10 to 15 city blocks of homes and businesses will be moved to higher ground. Many people are growing impatient and angry as their questions remain unanswered months after the flood swept through.

Doonan said the town submitted a proposal for the federal government to buy 82 of 292 houses that were damaged most critically. At first she was told that because Keithsburg's town-built levee didn't meet U.S. Army Corps of Engineers standards, no money would be available to buy the properties or repair the levee. But soon after, she was told the government had an obligation to provide money to protect the area's downtown because several of its buildings had been designated as historically significant.

"It's really hard on people there, because a lot of misinformation and conflicting answers are getting out," she said. "It's hard getting their lives back in order if they can't get these answers." In some cases, people decided whatever help was available wasn't worth the trouble it took to learn about it. "When they could, lots of business went ahead and took care of securing loans through banks on their own rather than what the feds are offering in low-interest Small Business Administration [SBA] loans," Doonan said. "They didn't want to mess with the government's paperwork, the unanswered questions. I can't say I blame them."

|

|

Heading south along the Mississippi from Keithsburg is the western hump of Illinois, where thousands of acres of farmland still sat under water at the end of last year. As winter settled in on the tiny riverside farming hamlet of Meyer, flocks of seagulls had nestled along shallow lakes that used to be corn and soybean fields. Just a handful of the 20-plus homes in Meyer seem salvageable. Some were damaged so severely residents could do nothing more than bum the remains to the ground. But the destruction wasn't enough to deter people from trying to live there again. "I feel like if people don't rebuild the houses there just won't be a town here anymore at all," said Mildred Reiter, who has lived in Meyer for more than 40 years. On a cold late November afternoon, she is bundled in a heavy coat, hat and scarf to survey once again what remains inside her small single-story home. Crews of local cleanup workers funded through Job Training and Partnership Act (JTPA) money, have not yet made it to Mrs. Reiter's home, and her carpeting still sits rotting beneath her ruined furniture. "What can you do?" she said with a weak smile. "There's nothing here worth saving. You have to start again." |

The sad stories of loss are the same in each of the small, modest homes left standing in Meyer: Childrens' toys, grandparents' antiques, sewing machines that helped clothe entire families are carted out and dumped in refuse piles. Yet for most people who lived here, the loss of their homes is secondary. It's the future of their farms that has them panicked.

"This isn't just where they live — it's their livelihoods, their careers," said Cynthia Allensworth, who coordinates flood resource centers in Adams and Pike counties. Immediately after the flood, emergency aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provided rent assistance and temporary trailer homes for people whose homes were flooded. Charitable organizations like the Salvation Army and Red Cross mobilized quickly to provide free hot meals, groceries and other household goods. But now that people have used up their emergency funds and are looking toward their future, they don't see as much help available, she said.

"A lot of these people lost all income for 1993, and now they're starting to wonder what kind of income they'll have in 1994, especially if there's spring flooding," Allensworth said.

14/January 1994/Illinois Issues

|

The vast majority of farmers — more than 90 percent — didn't carry flood insurance, and now must bear the cost of replacing destroyed grain bins, livestock houses and other farm buildings, as well as repairing costly farm machinery. They also have to wade through regulations on what standards these buildings must meet if rebuilt in the floodplain. At the same time, she said, many have been turned down for low-interest Small Business Administration loans based on previous years' income, and only limited grants are available. "I think people have the misperception that farmers who were flooded out are getting money, and that's not true," she said. "In fact, many probably can't afford to repair their machinery or even buy seed to plant for [this] year." To help, Allensworth has started an "Adopt-an-Acre" program, through which donations of $145 are sought — enough money to buy seed corn or beans, fertilizer and chemicals for one acre of farmland. 'That's if the ground's even dry enough to plant," she said. "If not, the money will be held in reserve until they can. "This is the only way I can think of to raise money for them," she said. "If they can plant, at least they have hope. We'd give them vouchers for seed, they'd take it to their own communities, and this way it would lessen the flood's economic impact on other businesses in river towns and cities." Allensworth sometimes splits her time between resource centers in Menden, west of Meyer, and in Hull, about 35 miles to the south. Staffed by JTPA workers, both offer free grocery items, coffee and donuts, and a place to sit and talk for a minute with other flood victims. |

|

Dan Lundberg, who farms more than 2,000 acres of corn, soybeans and wheat with his father and brother, visits the center in Hull in between rounds of supervising the town and farm cleanups. He heads a crew of nearly 40 JTPA workers who have been cleaning flooded-out houses, pumping basements and clearing farmland so debris won't ruin farm equipment. Literally tons of garbage had been removed by the end of the year.

These JTPA jobs are considered beacons of success amidst the flood-related despair. With all the farmers and others in related fields who lost their jobs and income with the flood, these temporary positions have kept lots of people busy and put money in their pockets.

"We have very high unemployment here otherwise," Allensworth said. "The question now is whether JTPA will be extended. [JTPA workers are limited to working 6 months or earning $6,000.] I've been told it would take an act of Congress to extend it — but so what? If congressmen could see how much it means to these people. ... It's definitely the only income for many of these families."

Lundberg, whose family has farmed in the Hull area since 1923, said the JTPA programs have been good for the community. But his experiences with other government-backed programs have gotten under his skin. The lessons learned from these experiences have made people bitter, angry — and sad. For instance, he said, when FEMA workers first descended on Hull, they told his father, Jack, he could receive an SBA loan of up to $200,000 to put into his farm and, since he was 76 years old, they told him, he wouldn't realistically have to worry about paying it back. "What they didn't tell him — and at age 76 he didn't read into it, although it may seem obvious to you and me — is that his heirs would have to repay the loan. And if they couldn't, the land would revert to the government," Dan Lundberg said.

He's also learned that many farmers are being told they're ineligible for low-interest loans because of previous years' incomes, even though most of that money went back into farm buildings and equipment, he said. "They come in raving about the 4 percent SBA loans they're offering, but that's only for people who have been turned down by a bank and are willing to put up with all the stipulations they carry."

Because many FEMA workers rotate through communities in crisis, those who provided initial information to Lundberg and others in the Hull area are long gone. In their place, he said, are others who are giving very different answers to their questions.

FEMA spokesperson Martha Wheeler said the agency's workers must rotate through areas as disaster situations occur. "There's no other way to staff these emergencies," she said. "But that shouldn't make the answers they give any different from each other's. Deadlines for extensions in applying for flood relief have changed three times, but our basic rules and regulations have not changed an iota since long before the flood began."

Even if the flood's victims did receive clear answers all the time, many of them still would face uphill battles trying to achieve what they feel they need most to recover and protect themselves. "It's not going to be easy for farmers to get what

January 1994/Illinois Issues/15

they want and need, which are 35-foot levees to hold back 500-year floods," said Lyle Nichols, unit director of the Pike County Cooperative Extension Service "The environmentalists and a lot of other people say, 'We don't want to pay for FEMA bills, levees, when you're going to be flooded again."

But he and others see a new levee system for the upper Mississippi as crucial. Since terrible floods destroyed large areas along the lower Mississippi in the 1920s, the Army Corps of Engineers has managed all levees below Cairo, Illinois, where the Mississippi joins the Ohio, he said. "Up north here it's a hodge-podge. Some are run by the Corps, some by individual drainage districts, some private, and many at different heights. If they had been a standard 35 feet we wouldn't be here talking about the flood. Farmers have been saying this for years, but the problem is not enough farmers will make enough noise to make anybody in Congress listen."

Blake Roderick, manager of the Pike County Farm Bureau, agreed. "There was over $20 million in damage here because of the flood ... and that's real property lost. When you look at what's happened to the whole economy of the county, when you include major interstates closed for a couple of weeks, railroad closed for a couple of months, it's hard to calculate. But the point we want to get across is while the cost of raising the levees would be kind of pricey, the investment would more than pay off." He estimated it would cost just under $1 million a mile to raise 54 miles of river levees and 50 miles of creek levees protecting 140,000 acres in Pike County and the surrounding drainage district. He knows such a solution would be difficult to get approved.

"Instead, people want to tear down 150 years of manipulation of the river. But our forefathers built those levees because they felt they were necessary."

These arguments probably won't be enough to steer Congress to a standard, Corps-maintained system of higher levees on the upper Mississippi, said Corps spokesman Peter Ves-tiger, although he added, "It's hard to speculate about what Congress may do."

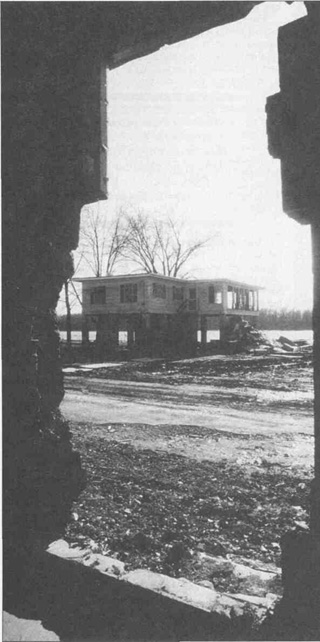

Some people never give up. This is Grafton where flooding left 203 of 383 homes under water. This is one of the homes undergoing reconstruction. Notice that the road even in December when this photograph was taken still looks like a dirt trail. Photo by Russ Smith |

From a historical perspective it doesn't seem likely either, said Corps historian John Anfinson. The levee system put in place in the Lower Mississippi Valley following flooding in the 1920s protected much greater areas of agricultural floodplain than exist along the Upper Mississippi. "Not only is it a different era environmentally, but a different set of circumstances down there," he said. "Implementing a similar policy here would be so contrary to the general opinion and general way everyone seems to be leaning. The most extensive plan I've heard is simply rebuilding what's there. This post-flood period represents an opportunity to recapture the floodplain to a lot of people." Towns along the river suffered varying degrees of damage, all of them pitiful. In some places, like Keithsburg, one-third of the homes were destroyed. In others, nearly half are beyond saving. But Valmeyer, about 30 miles south of St. Louis, is almost in a class by itself. The entire village of 900 was submerged under six to 12 feet of water. Left behind when the water receded was a virtual ghost town. Homes sit empty, marked universally by discolored water lines about 10 feet from the ground, "no trespassing" signs, and rusting piles of their former contents |

16/January 1994/Illinois Issues

heaped out front. There, the flood carried a harsh but clear lesson: It has been decided that Valmeyer will make a collective move about a mile or so northeast, up about 400 feet into the nearby bluffs.

The green trailer that now serves as Valmeyer's village hall is the sole point of activity. Inside, people orchestrate the village's move out of the floodplain to the 500 acres it is buying from a dairy farm corporation, where it will try to re-create itself. Spring is targeted for construction of the new homes and businesses.

"I think the biggest question that made people want to move was whether it will happen again," said Dennis Duffy, a maintenance worker for the village who was born and raised in Valmeyer. He, his wife and their seven- and 11-year-old sons are staying in a FEMA trailer in nearby Columbia until the new town is built. He summed up his reasons for hoping the town can stick together: "I was raised here, my wife was raised here, our families were all here. That's what we all have."

|

Mayor Dennis Knobloch pulls up in his black truck, mobile phone to his ear and orange sign taped to the window, reading "Village of Valmeyer, office of the mayor." Traveling between the green trailer, his gift store in nearby Maeystown — where he's been living since his home was flooded out — and meetings with every public agency imaginable has literally turned the truck into his office. It's the one thing that remains constant even as FEMA workers, and the information they offer, seem to rotate on a regular basis. "One thing that has gotten better, though we still have some problems, is that the federal government has been very slow to give answers," he said. "And when they have given answers, we can turn around and get another, different answer from the same agency. We're doing OK in the town — it's the farmers we're worried about. We've got 55,000 acres of agricultural ground that lies between us and the river. These people need to start putting things back together." |

|

Brothers Doug and Pat Sondag are two of those people. Their corn, soybean and livestock farms sit adjacent to each other, spanning more than 1,000 acres of land. "We need to know what we're gonna do with all the sand that's on our ground — one to three feet of it in some places," Doug Sondag said. "We need to know if we're going to be able to get flood insurance after this. But what we really need to know is if they're going to fix the levee right. Now it's just got sand in there; it won't hold. But when we talk to different people about these things, we get 10 different answers."

By not giving him clear answers, he said, he feels like the government is trying to force him off his floodplain farm. "We're just their scapegoat at the moment."

Knobloch still wasn't sure what could be rebuilt. "If they can't build new farm buildings on the bottom land, where can they store equipment?" he wondered. "If they can rebuild them, but they can't rebuild homesteads, there will be buildings full of expensive farm equipment and livestock without a home nearby for miles around. That leaves it open to vandalism and theft."

As executive director of the Southwestern Illinois Metropolitan and Regional Planning Commission, Tom Wobbe has helped coordinate recovery efforts in Valmeyer and surrounding communities. He credits the village's quick decision to move as one reason it's been listed as first in line of 209 communities requesting federal relocation funds. "There was general consensus of the village board and then the village population quickly to move above the bluffs rather than try to rebuild," Wobbe said. "The community has the urge to move forward and develop a new town. We've felt that time is our worst enemy. If too much goes by, eventually most people will disperse into other communities. Right now they are literally scattered — some have moved away, some in FEMA trailers, some with relatives. If they waited too much longer to make a decision on how to proceed, the town probably couldn't have been held together. They've literally gone at it full steam."

Wobbe echoes many others in his assessment of the federal and state governments' response to this new crisis. They, too, are learning lessons from the Flood of '93, just as the individuals who were hit by the water. "This is not a typical day-today, or even a typical disaster situation," he said. "They're still learning as they go through the process." But it doesn't seem as though this patience can hold out much longer. The cold weather is here, and the spring planting season is on its way. A new year is starting. But people are still figuring out what lessons the river taught in the last one.

January 1994/Illinois Issues/17

|

|