|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

costs are punishing every other state program.

The program is tangled with federal requirements and demands by

providers for reimbursements that cover costs, which keep going up

Some say it was inevitable for financial reasons. Some say it's part of an overall political strategy to force the federal government into addressing health-care reform, one way or another, and to give Illinois' Republican governor a distinct campaign issue in his bid for a second term.

No matter what the reason, Gov. Jim Edgar's call last month to experiment in running the state's Medicaid system represents a first step toward addressing a long-festering problem of skyrocketing Medicaid spending, which threatens to bust the entire state budget. The stakes are high: If something isn't done, the escalating Medicaid budget possibly could force the state to cut other programs, raise taxes or risk a near financial collapse of the entire Medicaid system.

|

|

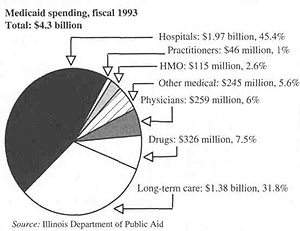

The fight over the proposed changes will be hot and heavy, but few disagree that something, somewhere, somehow has to be done about Medicaid's ever ballooning costs. The $4.6 billion Medicaid program, which has doubled in size in just the past two years, has an estimated operating deficit for this fiscal year alone of more than $1 billion. Whatever the merits, Edgar's plan is still significant for one reason: The very structure of the Medicaid system, the state's largest social service program that provides health care to the poor and long-term care for the elderly, is on the bargaining table, opening it up for long-term fundamental changes. Edgar's proposals fall generally into two categories: first, an attempt to pay off back Medicaid bills through refinancing of state obligation bonds, and second, revamping the way current medical services are delivered through the increased use of "managed care," starting in April 1995. The plan does not affect the 60,000 elderly residents now receiving Medicaid assistance for nursing home care, though state officials say they may eventually make changes in that program, too. The first part of the plan entails the state's refinancing about $1.5 billion in general obligation bonds and using the savings to pay off about $1 billion in unpaid Medicaid bills over the next two fiscal years. |

In the past, the federal government, which requires states to provide Medicaid services, has been extremely reluctant to approve requests by states to revamp their Medicaid systems. In recent years, however, the federal government has been more receptive to giving Medicaid "waivers" to states, such as Oregon and Tennessee, so that they can experiment with new systems. Edgar, who's very confident that the federal government will approve Illinois' proposed overhauling of the system, said President Bill Clinton, the former governor of Arkansas, understands the financial dilemma facing states regarding Medicaid. That's why Illinois expects to win approval from Washington, D.C., to overhaul Medicaid.

The intent of Edgar's proposed changes is simple: to save money. The state already uses some "managed care" for a small portion of its overall Medicaid population of about 1.4 million people. The Healthy Moms\Healthy Kids program, which provides medical services to about 124,000 pregnant women and children, carefully monitors exactly what

18/April 1994/Illinois Issues

type of medical services are given to clients and when those services are provided. The Department of Public Aid, which administers Medicaid, also has three Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in Chicago serving about 105,000 children and adults on Medicaid. Edgar wants more Medicaid recipients to use HMOs or variations of HMOs. The current "fee for service" program that most Medicaid recipients use that is, giving them wide flexibility to go to just about any doctor and hospital they want costs about $202 per month for each person. Most recipients don't abuse the system, but many go to expensive emergency rooms for even the most basic services. The average monthly cost for those using Medicaid HMOs, on the other hand, is about $113 per month.

There's another aspect of Edgar's plan that's causing deep concern among hospitals, doctors and others who provide the actual medical services: Edgar's proposed fiscal year 1995 budget includes only enough Medicaid money for nine of the twelve months of the fiscal year. The administration says that's because the new system would start in April. No one knows how much the new Medicaid program would cost until a final plan is ironed out over coming months, but the plan as outlined by Edgar is for the bills incurred in April, May and June under the new program to be rolled into fiscal year 1996 for payment.

Dr. Arthur Kohrman, chief executive officer at Chicago's LaRabida's Children's Hospital and Research Center, which has the largest percentage of Medicaid patients of any hospital in Illinois, said that fundamental changes in the state's Medic-aid system are now probably inevitable and that providers will work with the state on reforms. However, Korhman, who's also the past chairman of the state's Medicaid Advisory Council, said Medicaid providers are extremely nervous that the fiscal 1995 budget isn't fully funded and that state government may impose massive Medicaid cuts once a new system is in place. "To me, their numbers just don't add up," says Korhman, who refuses to endorse Edgar's plan until he and other providers see more details. "They're talking about cutting costs in an already massively underfunded program which already is deeply in debt. Maybe they can do it, but none of us can imagine where the heck they'll find the money."

Edgar, who describes Medicaid as the single biggest headache of his administration since he took office in 1991, said the state simply has to act now because it can no longer afford the current system. "We're out of money," he said in an interview before last month's budget address to the Illinois General Assembly. "We can't keep setting aside dollars for Medicaid without hurting a lot of other programs like education and others. There's no doubt the current [Medicaid] structure we have now, as set down by federal law and a patchwork of [legal decisions], isn't working. We need to scrap it. I think everyone understands we have got to do Medicaid differently than we've done in the past 20 years. We're at the point, cost-wise, where it's killing us."

|

How did Illinois get to the point where the governor is now talking of making major changes in the state's largest social service program? The answer may be a classic example of a good-intentioned government program gone horribly awry for many reasons: skyrocketing health costs in general; demographic and economic changes that have increased the number of people needing Medicaid assistance; federal mandates on states to increase Medicaid services without the federal money to pay for them; a seemingly harmless congressional amendment that's since been interpreted by the federal courts to mean that states must pay medical providers more money; powerful members of the U.S. Congress who resist calls to reform the Medicaid system; a health care delivery system that encourages welfare recipients to recklessly seek the most expensive medical services; and politicians who can't or won't confront the fact that the health system they have simply costs more money than they're willing to pay. |

To understand the current Medicaid dilemma and to understand why Edgar is demanding change, it's important to keep some things in mind.

First, this is largely an externally caused problem that's vexing every other state, not just Illinois. States across the nation are grappling with their own federally mandated Medicaid programs. The state of Tennessee has taken the most radical step toward confronting its mess by scrapping its old Medicaid system, in favor of moving welfare recip-

April 1994/Illinois Issues/19

ients into the state's health care program for state employees. Other states are experimenting with more modest "managed care" programs to control costs.

Second, states have very little wiggle room, due to federal laws and federal court decisions, on how they can run and finance Medicaid services. That's why Edgar is requesting a federal waiver to experiment with new programs in Illinois. That's also why so many governors are looking to the federal government to reform the entire health care system in the United States. "I think states [across the nation] are reaching the breaking point financially, which is why you see things being done by the federal government on health care reform," says William Kempiners, executive director of the Illinois Health Care Association, which represents about 405 long-term care facilities that provide Medicaid services to recipients. President Bill Clinton has proposed an extensive revamping of the nation's overall health care system, but few know what ultimately will be produced after protracted debate in Congress and after almost inevitable changes in Clinton's plan. Governors across the nation say they simply can't wait, for financial reasons, for the federal government to take action on the health care front years from now.

Third, one of the more frustrating aspects of Medicaid is that most people just don't care about Medicaid, let alone understand it. Medicaid terms like "diagnostic related groupings" and the "EPSDT process" are enough to make even the most knowledgeable insiders a little groggy. "It [Medicaid] is incomprehensible to most people," explains Kempiners. "It's not sexy. It isn't about roads and bridges and other things voters and even lawmakers understand. They don't want to deal with it."

Started in 1965, Medicaid initially was just one of many Great Society programs born out of the 1960s optimism that most social problems could be solved through good intentions and lots of money. At first, Illinois' Medicaid program was modest. Its budget of $87 million provided minimum health care to about 390,000 welfare recipients. Today, Medicaid has turned into a $4.6 billion program serving 1.4 million poor people and about 60,000 elderly residents in long-term care facilities. A double-digit inflation rate for health care services in general has obviously been a main cause of the vast growth. The U.S. Department of Labor's Bureau of Statistics says, for instance, that the overall cost-of-living index increased by about 45 percent from 1983 to 1993, but health care costs increased by 100 percent over the period of time.

There are, however, other demographic and governmental factors at play: an aging population that requires more and more people to seek long-term care; an increase in the number of those living in poverty; federal mandates on what services must be provided and on who's eligible for Medicaid; and federal court pressure to pay a "reasonable" rate to hospitals, nursing homes, pharmacies and others providing the actual health services to recipients.

To get an idea of the gargantuan size of Medicaid today, consider the following:

One in three births in Illinois is now paid for by Medicaid.

One in every two children in Chicago is eligible for Medicaid benefits.

Six out of every ten elderly residents in long-term care facilities in Illinois are on Medicaid.

New federal mandates imposed since the late 1980s alone such as increasing the income eligibility for women and children on Medicaid cost the state's general revenue fund about $141 million per year. That's roughly the same amount of money used to fund 25 state agencies, including the departments of Agriculture, Conservation, Energy and Natural Resources, Mines and Minerals, and Labor; the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency; the Illinois Arts Council; and others.

Medicaid's share of the state's general revenue fund has increased from about 13 percent two decades ago to about 22 percent today. The share of money going to education, meanwhile, has declined from about 42 percent to 35 percent over the same period of time. It's hard to escape the conclusion that there's a direct correlation between Medicaid and education funding, though other state spending policies obviously have contributed to the decline in state dollars going to education.

Combined with the state's massive $700 million self-insurance program for its 300,000 state employees, dependents and retirees, the state of Illinois has simply become, by far, the largest health care provider in Illinois.

Officials say health care inflation, demographic changes and federal mandates have been bad enough, but now they're struggling with a problem that is potentially even more daunting: federal laws and federal court decisions demanding that states ante up more money for the vast array of Medicaid providers, such as hospitals, nursing homes, pharmacies, general practitioners and others. More than anything else, the recent pressure to give providers more money is the final straw that broke the Medicaid camel's back, both in Illinois and across the nation.

The reimbursement dispute centers on the so-called "Boren Amendment" passed by Congress in 1981. The amendment requires states to reimburse medical providers at a "reasonable" rate necessary to provide an "economically and efficiently run" health care system. The very vagueness of the Boren amendment has invited countless lawsuits. Joan Walters, Edgar's budget director, asserts that the initial intent of the Boren amendment was to put a "ceiling" on Medicaid costs to protect states, but most federal courts have since interpreted the amendment to mean that states must pay a "minimum'' amount of money for the health services rendered by Medicaid

20/April 1994/Illinois Issues

providers. Medical providers usually win their lawsuits based on the interpretation that the Boren amendment means states must pay them higher fees.

Illinois was lucky in one regard during the late 1980s and early 1990s. It had won a special waiver from the federal government that temporarily exempted Illinois from the Boren Amendment. As a result, Illinois had a reimbursement system called "I-Care," which paid a set, negotiated amount of money for each day of medical services provided by hospitals and other Medicaid providers. I-Care spending was relatively predictable and allowed Illinois to track its Medicaid expenses better than it had before. The state loved I-Care. Medical providers hated it. They felt the state was reimbursing them for only about 60 percent of the actual costs of providing Medicaid services. They said the state was simply shifting costs around. By not fully reimbursing them for Medicaid services, providers said they had to make up the difference by charging non-Medicaid patients higher rates.

The bottom effectively fell out from under Illinois in 1991, when the federal government strongly indicated that it would not renew the waiver exempting Illinois from the Boren Amendment. Good-bye, I-Care, the predictable reimbursement system that set fees on a daily rate. Hello, Diagnostic Related Groupings, a fluctuating reimbursement system that's not nearly as predictable.

Reacting to the federal government's decision and reacting to calls by Medicaid providers to change the I-Care system, Edgar initially proposed in 1991 that a new "assessment tax" on hospitals and nursing homes be imposed to nab more federal funds and to start complying with the anticipated higher costs of the Boren Amendment. The state also agreed to phase out gradually the I-Care system. Under the assessment program, hospitals and nursing home were assessed a "tax" based on their Medicaid caseloads and Medicaid receipts, but they were guaranteed to get back, at minimum, the exact amount of money that they paid into the program. The beauty of the plan was that: Medicaid providers automatically received their money back and they received a total of $425 million in matching federal funds in the first year of the program. Medicaid providers still felt their services were being underfunded, but they appreciated the extra federal cash being pumped into the Medicaid system.

The federal government, however, didn't like the assessment program being run by Illinois and most other states, which also were using their own versions of the assessment tax to nab federal dollars. In 1992, the U.S. Congress passed a law that said there could no longer be a guarantee that providers would get back what they paid. Also, the tax would be on the overall gross income of a provider and not just on its Medicaid receipts, and the revenue would then have to be distributed based on Medicaid caseloads at individual hospitals and nursing homes. Thus, inner city hospitals and nursing homes, which have lots of Medicaid patients, received most of the money from the modified "assessment" program. Suburban hospitals and nursing homes, which have fewer Medicaid patients, were paying lots of money into the system but weren't getting much back. Suburban Republicans despised the new reimbursement system, which was dubbed the "Robin Hood Assessment Plan."

In 1993, suburban Republicans finally succeeded in at least getting rid of most of the $6.30 per day tax on nursing home residents, otherwise known as the "granny tax." After a two-week overtime session last July, lawmakers ultimately approved a 14 cents per pack tax increase on cigarettes, as part of a compromise package to reduce the "granny tax" to $1.50 per day.

The dispute over the cigarette tax largely overshadowed a far more ominous development in 1993. The state was finally phasing out the old I-Care reimbursement system in favor of a far more complex and flexible "diagnostic related groupings" (DRG) reimbursement system. Whereas I-Care provided a flat daily fee for health services, the new DRG system fluctuates according to the different types of services provided: A tonsillitis costs this, an appendectomy costs that and so forth. The DRG system is supposed to reflect more accurately the actual costs of providing medical services to Medicaid recipients.

Unfortunately for the state of Illinois, the DRG is perhaps too accurate in estimating medical expenses. Costs skyrocketed so fast this fiscal year that the state unexpectedly found itself staring at a more than $1 billion hole in the Medicaid budget. The administration insists that the cost of the DRG system in its first full year was nearly impossible to estimate. Whereas I-Care simply paid a set daily rate for all medical services, the state had never kept track of the number of actual tonsilitises, appendectomies, broken legs, cancer treatments and scores of other health services. Without those numbers, there was no way to predict how much the DRG system would actually cost, the administration said. Democrats criticized the administration for its faulty estimates, and some even accused the Republican administration of deliberately low-balling initial DRG costs to downplay a looming Medicaid deficit.

Initially, Edgar proposed last December that Medicaid reimbursement rates be cut by about 9 percent to stem the flow of red ink, but the Illinois Hospital Association threatened a lawsuit. The administration, undoubtedly aware of the legal precedent established by the Boren amendment, quickly backed down. A stopgap compromise was reached eventually, basically to string out Medicaid payments and to freeze rates for 18 months. The compromise dealt only with the current deficit this fiscal year, but now there's another deficit forecast for next year, perhaps much larger than anything the state has

April 1994/lllinois Issues/21

yet seen. And there likely will continue to be Medicaid deficits each year thereafter because of the multitude of financial pressures on the state, from general health care inflation to the Boren Amendment to demographic changes in the population.

And that brings it all back to why Edgar proposed his Medicaid reforms in his budget address last month: The state has to do something about the escalating Medicaid budget. The only alternatives to reforms are raising taxes or cutting other state programs to pay for Medicaid. No one expects Edgar and lawmakers to approve a tax increase in an election year. Few expect Edgar and lawmakers to cut other programs, possibly even education, to fund Medicaid. So reforming Medicaid is arguably Edgar's only realistic option left.

In some respects, Edgar's proposed reforms outlined last month appear to be a variation of the old I-Care system. It's true he wants to have set rates established on a monthly basis (like I-Care), but he's actually carrying his reform proposal much further. I-Care allowed Medicaid recipients almost unlimited access to just about every medical service they may have needed, but a new "managed care" system would strictly monitor and limit when, where and what type of services recipients could receive. It's what he's banking on to get control of the Medicaid system.

Before his budget address last month, Edgar met with reporters to brief them on the general outlines of his proposed reforms. He repeatedly emphasized to them that Medicaid spending has doubled just in the past two years. He then pointed to a chart showing how Medicaid spending is outstripping education spending. Edgar wasn't being very subtle: If something isn't done about Medicaid, then other programs will eventually suffer the consequences.

Jay Fitzgerald is a Statehouse reporter for the State Journal-Register in Springfield.

|

Edgar's proposal for Medicaid change; Democrat Jones also suggests changes Gov. Jim Edgar laid out a plan to confront Medicaid's ever-escalating costs and growing mountain of unpaid bills to hospitals, pharmacists and others providing services to Medicaid clients. The day before Edgar proposed his plan as part of the fiscal year 1995 budget. Senate Minority Leader Emil Jones Jr. (D-l , Chicago) proposed his own plan. Both agree on two concepts. Medicaid services should be provided on a managed care basis to bring down costs, and fraud and abuse should be stymied by using some type of verification system. Edgar's proposal goes farther in its separate attempt to clear up the current back-log of Medicaid payments to providers and to assure providers that the state under a new "managed care" Medicaid system will stop being a deadbeat in paying its bills. Edgar's proposal includes the following: Restructure state debt to gain sufficient one-time revenues for the state to pay off $750 million in bills owed mainly to those who provided services to Medicaid clients. Any unpaid bills still remaining under the current Medicaid system would be paid off in the following fiscal year. Put the state payments to Medicaid providers on a fixed schedule during the fiscal year. Move toward a managed care system, allowing Medicaid clients to chose from one of five options Edgar wants in place by April 1, 1995: 1. a managed care system under a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO); 2. an integrated health services consortium offering a managed system of primary, secondary and tertiary care; 3. a coordinated system of care with access provided by a primary care physician selected by the client and providing fee-for-service care; 4. a traditional system of private health insurance with state-paid (Medicaid reimbursable) premiums; 5. a system of managed care services for clients in long-term care. Require that every pharmacy requesting a Medicaid reimbursement include the license number of the physician prescribing the drug. Begin a study to improve the state's computerized tracking, monitoring and reporting systems for Medicaid clients and providers. Use plastic "swipe" cards for Medicaid participants, tied to a new electronic system that would verify eligibility, but the proposal is only for a pilot basis at sites in both Chicago and downstate. Jones' proposal concentrates on estab-lishing a way to prevent abuse and fraud in the current Medicaid system, but he also proposes that Medicaid recipients in two pilot areas, one in Chicago and one down-state, be required to enroll in an HMO. Jones also proposes a second pilot project to be set up in a dozen sites in Cook County by the Department of Public Aid by December 31, 1995, to include the following: Establishing a computer system that would allow "on-line" access to information in order to verify that a person seeking Medicaid benefits is, in fact, eligible. The health care providers in the pilot project areas would have access to the system, which the Department of Public Aid would be capable of updating electronically and immediately. Initiating the issuance of Medicaid health care cards to those who are eligible. Included on these cards would be the person's photograph in order to prevent the card's use by someone who is not eligible plus electronically coded information specific to the cardholder's medical history and payment responsibilities. Jones' says the setup for the on-line computer verification system could be done with a onetime cost of $25 million. He says half would be paid by federal dollars. Many more details will need fleshing out on Edgar's proposals and also on Jones' as well as a scorecard on which partisan is bashing whom. Caroline A. Gherardini |

22/April 1994/lllinois Issues

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |