|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

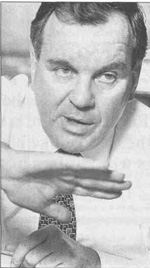

pushing instead for an image of a man who gets things done in

every area of the city. Unlike his father, this Mayor Daley

compromises with his foes instead of punishing them

|

Want to know how to irritate the mayor of Chicago, Richard M. Daley? Ask him a question or two about politics, as in, "Who do you think will run against you next time?" or "Do you anticipate strong opposition in 1995?"

Daley generally shakes his head at such queries or waves them off indignantly. "If I had to worry about my election, I'd never make a decision here and my role is to make decisions," he said during an interview with Illinois Issues. "I don't consume this political stuff. ... I'm not a political junkie. ... [Working in government] is where you get things done. The political side is just conversation." Daley is much more willing to talk about policy issues, whether the subject is property taxes, crime, schools or his assertion that he's wrung more services from a leaner city budget. "I'll compare my record against anybody's" is his mantra, the closest thing he has just now to a campaign slogan. The man whose last name still evokes everything political about Chicago will seek reelection in 1995 as an apolitical incumbent, one who could care less about who's the boss in which wards. His preferred image: a mayor as policy wonk. Quiz Daley and his advisers about his approach to running the city, and you'll be told about a mayor who keeps track of potholes and burned-out streetlights from the back seat of his city |

Photo by Jon Randolph |

That strategy of compromise keeps his political enemies off balance. They have learned that they cannot run against this mayor the way they would have opposed his father — by mounting a crusade against a one-party autocracy that guarded

the spoils jealously. The mayor certainly is Da Boss's son, but to judge him as just an updated version of his father, gussied up and homogenized for today's tastes, is to seriously underestimate him.

Despite his predilection to be gung-ho for glamorous pro-

April 1994/Illinois Issues/23

|

jects such as a new airport or gambling casinos, Daley is most comfortable governing with limited, defined goals. He is a utilitarian mayor who knows he will be judged by the mundane business of City Hall, whether the ambulance comes when called, the streets look clean and the sewers keep flowing. He knows he cannot eliminate crime or poverty or reverse the economic and social changes that have wrought so much pain in his city. But he believes that if his government works well, it can enhance Chicago's livability. Different Chicagoans have their gripes about Daley, but his approach bars many from getting angry at him, and anger would be needed to ignite a successful campaign against him. Daley's compromises work to snuff out even the smallest political brushfire. When it comes to sensing difficult issues, "the mayor has the best antennas of them all," says Mary Sue Bar-rett, his chief of policy. "One of the refrains the mayor uses often is, 'Have you lined up the support for this or that proposal.'" "There's a new approach by his handlers, which is, 'Don't fight 'em, join 'em.' It's disarming, in a way," says Alderman Lawrence S. Bloom, who represents the Hyde Park and South Shore-based 5th Ward, long known for its independence. Bloom has a recent example of this new approach; in February, he proposed an ordinance to require competitive bidding among firms seeking to underwrite city bond issues. It was a sensitive issue for Daley because his brother, Michael, has received a cut of the bond business from underwriters. Rather than consign Bloom's ordinance to committee limbo, the mayor agreed to seriously study it. He says he may introduce it with some changes, but playfully wonders why Bloom never produced the ordinance during the years he supported Mayor Harold Washington in the City Council. An aide to Daley said the administration may support the ordinance if it doesn't hurt city efforts to allocate bond business to minority-owned firms. Some would say that's a real switch — a Daley fretful about doing something that would hurt minorities. But the example shows how sensitive Daley can be to anything that might set off that seminal anger in a multicultural city. There are other examples of Daley meeting certain aldermen halfway, or more, on given issues. In 1992, a number of his allies raised public and private objections to a proposed $48.7 million property tax increase in his 1993 budget; Daley shaved the increase by $20 million and has since held the line on the tax levy. Although it included hikes in taxes for parking, liquor and amusements, among sundry items, Daley's 1994 budget was adopted 47-0, the first time in anyone's memory a budget sailed through without a dissenting vote. One reason for the unanimity was that Daley scaled back a plan to substantially increase taxes on utility bills; he and the aldermen agreed on a 1 percent hike. Another reason was a Some would say that's a real switch — a Daley fretful about doing something that would hurt minorities. But the example shows how sensitive Daley can be to anything that might set off that seminal anger in a multicultural city Daley commitment to increase funds for affordable housing by nearly half — to $152 million a year for five years. The increase had been a pet cause of housing groups, who proposed the city find the money using such devices as bond issues and tax-increment financing. Daley surprised them, and deprived opponents of an issue, by buying the plan with minor revisions. Daley says he accepted it not for political expediency but because the housing advocates presented a plan his administration deemed workable. |

|

"Compromise — that's what people want," Daley says, adding that continually doing battle with opponents is a "waste of time." Alderman Patrick J. 0'Connor, a reliable Daley backer from the north side, says the housing ordinance underscored an administration commitment to "get everybody in on the decision-making." 0'Connor says Daley and his aides have learned that inclusiveness can be a political tool. "They cover the bases. They brief the aldermen when tough issues arise. They even have the department heads do it." Earlier in his tenure, Daley was more aloof, according to 0'Connor. "They really thought that if we don't tell the aldermen this is an important issue, we won't have to waste the political capital for their votes. They now know there's not a lot of political capital anyway." Alderman James F. Laski of the city's southwest side has defied Daley on some issues. Laski recalls that Daley killed his proposal in 1992 to require carbon monoxide detectors in homes that are newly built or that get new furnaces, arguing that it would be burdensome law. However, the mayor ultimately backed an ordinance that went further by requiring the detectors in all homes and hotels with forced-air heat. The City Council adopted that ordinance in March. Critics give Daley points for his record in two other areas — community policing and deciding when city services are to be or not to be privatized. Community policing, which involves assigning extra officers to walking beats, is at work in five of the city's 25 police districts. Officials say the program has reduced crime by forging ties between neighborhoods and the police, and Daley says he wants it implemented city wide in 1994, although budget documents appear not to account for that change until late 1995. Daley has privatized about 40 city government functions, but he's "unprivatized" a few — bringing them back in-house — to the delight of aldermen who don't want city workers to lose their jobs. Since taking office in 1989, Daley has shed about 2,000 from a payroll now totaling about 39,000. One of his leading City Council antagonists, Alderman John 0. Steele, however, charges that in one layoff of 800 people, 75 percent of those affected were black. Daley's aides say that isn't true and that since 1989, minority representation on the city payroll has grown from 43 percent to 46 percent, despite the cutbacks. |

The mayor contends his decisions on privatization are motivated only by a concern for providing services cheaply. His aides say the city's alcohol and drug abuse clinic on the west side has served more clients for less money since the operation was privatized. Daley notes that maintenance of City Hall was shifted from an outside contractor back in-house after a municipal union made a cost-saving proposal.

Besides privatization, Daley has exhibited a willingness to reshape the city bureaucracy. Separate units for planning, economic development and landmarks preservation have been folded into one superagency, and the streets and public works departments have seen their duties revamped. But even here, Daley has compromised. He recently bowed to pressure from a prime ally, Alderman Edward M. Burke, chairman of the council's Finance Committee, and scrapped plans to disband the Police Department's Marine Unit. Burke argued the unit is important to the safety of Lake Michigan boaters.

There are only a handful of what could be called "anti-administration" aldermen, maybe five to eight out of the 50 council members, depending on the matter at hand. Nevertheless, some take credit for inspiring Daley's initiatives, including installation of metal detectors in schools and a proposal for the city to limit increases in taxicab lease rates. Daley, who once shunned the taxi regulation, has embraced the plan because of criticism that each time the city raises fares for drivers, cab companies grab the money by hiking lease rates the drivers must pay.

One anti-Daley alderman, Helen Shiller, contends the mayor's compromises are not a sign of political strength. "I think it reflects that they know they're vulnerable in 1995," she says. Alderman Steele, who says he may run for mayor if he's convinced the race is winnable, praises some of Daley's policy decisions but wonders about fellow-through. "In my dealings with him, I've found that he's always a gentleman and that he makes certain promises, but that once something goes to the department level, it just doesn't get done," Steele says. He says he's suspicious of Daley's commitment to community policing, for example, citing the promise of 700 additional police officers to a force of 12,000 three years ago. Daley broke that pledge to the chagrin of many aldermen. As it is, Daley has increased the force by 600 and has budgeted for another 470 officers in 1994.

Steele also thinks he has an issue in Daley's minority contracting practices. While the administration says it is exceeding statutory minimums by issuing 35 percent of city contracts to firms headed by minorities or women, Steele contends those

April 1994/Illinois Issues/25

numbers are bulked up by companies fronted by white women. Thus, he says, minorities are denied a fair shake. Mayoral aides contest that assessment with data showing that only 5 percent of city contracts went to companies run by white women in 1992 and 1993. Black contractors were awarded about 13 percent of city business those years and Hispanics nearly 9 percent, according to the city's Purchasing Department. Daley and his aides say they're only doing what's right on the contracting question. The political side, however, is that each time a minority business gets a city contract, that's one less source of money for a mayoral candidate hoping for significant minority support. Many of these minority firms have turned around and enriched Daley's own campaign kitty.

Shiller and Steele are among the most acerbic of Daley's critics in the council. But a curious pattern emerges when aldermen and other politicians are asked to talk about the mayor. A few allies criticize Daley when it's agreed that they won't be quoted by name while some in the anti-administration column don't mind praising him for the record. Here's the view from one of the anonymous "allies":

|

"My people aren't very happy with Daley," says a prominent Democrat from a white neighborhood that has generated huge vote returns for the mayor. 'They think he hasn't done enough for this area, that he's raised property taxes and that too much money has gone into the minority neighborhoods." In truth, city government's property taxes have risen far less than those for the schools, county government and other agencies with a share of the tax bill. "That doesn't matter," the Democrat says. "When people get their tax bill, they think of Daley."

But this source adds that, given the racial chasm in Chicago politics, his area will again support Daley against a black opponent. But if the candidate is Cook County Clerk DavidT). Orr, a white mayoral prospect who appeals to some minorities and progressives, Daley "will have a real problem," the source says. Another Daley supporter likened the mayor's political support to that of President George Bush during the Persian Gulf war — it's broad but not too deep and any miscue could cost Daley dearly. |

Chicago is a city of neighborhoods but politically organized into 50 wards. Photo by Jon Randolph |

For the other point of view, however, there's Alderman Toni Preckwinkle, who asserts upfront when asked about Daley that her anti-administration credentials are solid. Then she adds, "The fact of the matter is that the mayor and the executive branch have been very helpful in my community." Daley has endorsed a bold redevelopment plan for North Kenwood and Oakland, two poor communities within Preckwinkle's ward. A comprehensive commercial and residential development can succeed there, Daley aides contend, because 70 percent of the land is vacant and the city holds title to most of it. With $1.2 million from a foundation, the city is preparing a development plan for the area and hopes that banks, facing federal pressure to loan more money to minorities, will provide the capital.

Or there's Joseph Moore, an anti-administration alderman who's nevertheless grateful that Daley chose his Rogers Park ward as a pilot site for community policing. One of the mayor's enduring attributes is fairness in allocating city services, says Moore, an Orr protege. Moore says Daley has permitted critics to make headway on some fronts and issued several laudable appointments. But, saying he's unlikely to endorse Daley for another term, Moore comments, "The problem is he's always reacting. He's being forced into these positions and he doesn't come to them naturally."

And Moore faults Daley for a "lack of vision," a critique Daley heard frequently about a year ago, when he was pursuing two big-ticket development projects that haven't come to fruition, a new airport and a land-based casino. Daley now acknowledges he's close to an agreement with Gov. Jim Edgar on a riverboat gambling license for Chicago. He says the riverboats, as part of a larger amusement park-like setting, could produce significant jobs and revenue for the city.

The charge that Daley has focused on the large-scale economic development projects to the detriment of smaller ones is one he bristles at. His office readily produces a list of companies that he says were attracted to or stayed in the city under his watch. Daley cites his support for restrictive zoning districts that permit only manufacturing uses, a device that's supposed to keep factories from being chased out of gentrifying neighborhoods. Daley's response on this issue has won praise from many community development groups, who also like his stepped-up program for infrastructure work funded by bond issues. This year, the city plans to resurface five miles of residential streets per ward, compared to its usual two miles.

Using language similar to Moore's, Orr, who won't say if he'll run for mayor, faults Daley for a "lack of leadership and vision" on education, economic development and other issues. "He's probably doing the best he's capable of," says Orr, who is running for reelection as county clerk this year.

But "lack of vision" doesn't make for a snappy TV ad or get neighbors talking about throwing the bums out. Jane Byrne's issue when she beat Michael Bilandic was the city's inept response to a snowstorm in 1979. Harold Washington had Byme's sacking of high-profile black appointees in

26/April 1994/lllinois Issues

1983. As the strategizing for the next mayoral race begins in earnest, those who would dethrone Daley find themselves lacking an issue that galvanizes campaign money and volunteers. The coalition of blacks, Hispanics and liberal whites that broke apart amid disorganization and bickering after Harold Washington's death in 1987 has become the Humpty Dumpty of Chicago politics — nobody has put its pieces together.

There are issues that could be used on Daley, however. Chicago schools still lurch from crisis to crisis, although Daley insists he's helped that situation to the extent he can. He says he's hampered by the requirement that he appoint Board of Education members only from a list he gets from education groups. The process allows the board and school groups to tell him to stay out of their affairs except when they need his clout, Daley says. Accordingly, Daley's staff is rounding up support for legislation that would allow him to appoint some school board members without intervention.

Even if Daley is a "hands-on" manager, a few matters on management have caused embarrassment. Two years ago, city officials mishandled warnings that the Chicago River could flood the Loop's freight tunnels and the buildings connected to them. And Daley has been pilloried for cost overruns on the city's $225 million police communications center being constructed on the west side. None of this, so far, has pierced Daley's armor.

Whether he acknowledges it or not, Daley has gained from his opponents' disarray and has abetted it by alternately stealing their thunder or managing the city in a way that mutes criticism. He got elected in the first place because he correctly saw that, in the aftermath of the race-based Council Wars, Chicagoans were tired of name-calling and ready to move on. He took office in 1989 with an eloquent call to "lower our voices and raise our sights," and even his detractors concede that he respects a pattern of fairness in city services that was Harold Washington's most significant achievement in office. That's no small thing in a city where some people still think their garbage won't get picked up if they vote the wrong way.

But maybe there are times when the press isn't around and Daley allows himself to smile at his good fortune in politics, kick back at the City Hall desk his father used and enjoy a good cigar. If so, he isn't admitting it. Daley was asked if he doesn't even talk politics with close friends at 10 o'clock at night after a couple of beers. "I don't get into this," he replied. 'That's the least of my worries in the sense that at 10 o'clock at night, I'm going to bed."

David H. Roeder is editor of Chicago Enterprise magazine, which covers economic development issues. He is the former City Hall and political editor for the Southtown Economist

|

Early posturing for Chicago's 1995 mayoral election

Not everything about Chicago politics has changed. Some ward organizations still turn out a mountain of votes for their endorsed candidates. And the Chicago-centric view still holds that the mayoral race is the main event, bigger even than the highfa-lutin offices like governor and senator. Heck, the city's turnout for the mayoral race has exceeded that for the presidential contest. Mayor Richard M. Daley says he will announce later this year that he will seek reelection. His opponents float various possible candidates. Some tout Joseph Gardner, a commissioner of the Water Reclamation District and once one of Harold Washington's chief political operatives. Others ex another campaign from former Illinois Appellate Court Justice R. Eugene Pincham, who opposed Daley under the banner of Harold Washington Party in 1991, and still others look to Alderman John 0. Steele or Cook County Clerk David D. Orr. The dilemma here is racial; most of the anti-Daley crowd would rather support a black, but Orr, the only white on their list, may be the candidate with the strongest appeal to all races. The racial composition of Chicago's voter rolls demands at least some coalition-building. Juan Andrade Jr., president of the Midwest-Northeast Voter Registration Education Project, figures that about 8 percent of the city's 1.3 million voters are Hispanic, with the remainder almost equally black and white. Although Hispan-ics strongly backed Harold Washington, Andrade says Daley attained 70 percent of the Hispanic vote in 1991. Pincham, when asked about Orr's merits as a candidate, has an arch response: "I don't think David Orr is in a position to represent the African-American community." He reviles Daley for "corruption and pinstripe patronage" but has no stronger example than the brother's bond business. He assails Daley for seeking a casino without a referendum, but surveys show Chicagoans are ambivalent about gambling's onset, Pincham won't disclose his plans but seems to have himself in mind when describing the kind of candidate he'd like: "I think people will unite behind a candidate who is trustworthy and who has proven he can stand up for the community." But Bruce E. Crosby, a black political activist on the south side, believes Pincham and even Gardner exemplify the problem and not the solution for defeating Daley. He aceuses both men of being stooges for the mayor and says Daley has "bought off" black politicians and business leaders "whose job is to prevent unity." Crosby lost a race for Cook County Board president in the Harold Washington Party's March primary but says he will build the party into a progressive force. "Daley is easy to beat. The problem is beating his buffer zone within the black community," Crosby says. For Chicagoans, the idea that they have a mayor who may enjoy policy more than politics takes some getting used to. But perhaps the image Daley promulgates is nothing but an extension of today's politics, which sees party organizations waning in favor of candidates with their own networks of support. Daley himself says the independent voter is supreme, so politics for him becomes a self-centered game, albeit a serious one. He believes voters, without loyalties to a Democratic machine, will use more objective standards to judge him. With less patronage and public works favors to dole out, Daley fears he cannot ride to reelection atop an army of precinct captains. In many wards, the army has given up, died or moved to the suburbs. Daley is expected to enter the Democratic primary in February 1995. The survivor of that race will go to the general election in April facing possibly two challengers—a Republican and a Washington Party candidates David H. Roeder |

April 1994/Illinois Issues/27

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |