Finding a way to pay for college

With prospects for state funding dim and tuition skyrocketing,

one university president has a new idea: scrap the system that

rewards the rich and penalizes the poor

By MICHAEL HAWTHORNE

Talk to any parent with a son or daughter in college and the conversation quickly focuses on money — usually, the lack of it — to bankroll the escalating cost of attending a four-year university.

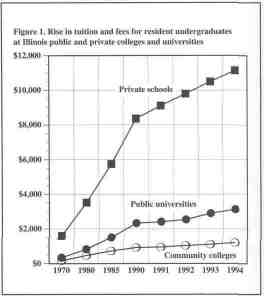

Tuition at the state's 12 public universities will jump between 3 percent and 11 percent this fall after increasing at nearly triple the rate of inflation during the 1980s.

State lawmakers, reflecting constituent concerns that public universities are becoming less affordable for students from low- and middle-income families, are pressuring school officials to hold down costs and streamline programs instead of boosting tuition again. "You cannot continue the kind of cost curve we're seeing," Sen. Steve Rauschenberger, an Elgin Republican, told a group of university presidents during a March meeting of the Senate Appropriations Committee.

Most of the presidents predictably pleaded for more state support to curb higher tuition, saying they need money for undergraduate programs and faculty salary increases. But at least one — Thomas Wallace, the president of Illinois State University in Normal — thinks lawmakers and university chieftains have got it all wrong.

What Illinois colleges and universities really need, Wallace says, is a new way to fund public higher education. Noting that state support isn't keeping up with increased costs, he argues the money woes at his institution and others will continue until decision makers scrap the low-tuition mantra that's ruled public higher education for decades. Such a policy may have been wise years ago as a mechanism to ensure access to higher education for all, regardless of income, but today it rewards the rich at the expense of students from low- and middle- income families.

"If you go over to the University of Illinois and walk by the Delta Gamma house, there are all sorts of spiffy little sports cars out front," says James Nowlan, executive director of the Illinois Tax Foundation, a public policy research group. "It's a sign that the affluent have found a bargain in public higher education. But is low tuition for the rich an appropriate objective of state government?"

Wallace's proposed solution — higher tuition paired with increased student financial aid — is the subject of intense debate within the Illinois higher education community. While he may regard his ideas as revolutionary, some of his colleagues at other state universities see him more as a renegade. Says University of Illinois President Stanley Ikenberry: "We need to hold tuition increases to the rate of inflation, or we are going to face a backlash."

"There are a lot of people happy with the status quo," Wallace says, responding to his critics. "The General Assembly doesn't see any contradiction in being both for low tuition and low taxes, and I think there are a lot of people in higher education playing that same game. But anybody who thinks we're going to get more tax support in great numbers for higher education must be smoking something."

The numbers suggest he may be right. For more than a century, public higher education has operated under the assumption that the cost of a college education was to be shared by individual students and society as a whole. A 1973 report by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, cited nationwide as a benchmark, suggested tuition should pay one-third of the cost to teach students, with the remainder coming from state tax dollars.

However, tuition now pays for about half of the total instructional cost at Illinois public universities, according to the Illinois Board of Higher Education (IBHE).

The problem: state funding for higher education has been flat for more than a decade. Despite skyrocketing tuition, faculty salaries aren't keeping pace with other states — let alone inflation. Students increasingly rely on loans rather than grants because need-based financial aid isn't keeping up with escalating college costs. Universities are cutting programs just to get by.

Moreover, all these changes come amid stiff competition between public and private institutions for the dwindling number of potential students now that the baby boomers are out of school.

Lawmakers say they are outraged by reports that show public university tuition increased by 278 percent between 1980 and 1994. But when adjusted for inflation, combined tuition and tax support per full-time student actually dropped to $3,186 in 1992 from $4,396 in 1980 and $5,242 in 1970, in part because there were about 170,000 more students in 1992 than 20 years earlier, according to the IBHE.

Nowlan says that funding trend isn't likely to change in the near future.

The period after World War II to the early 1970s represent-

24/May 1994/Illinois Issues

ed the "golden era" of higher education in the United States because there were infusions of both students and money, Nowlan points out. Like most states, Illinois' changing state budget priorities have siphoned away money that traditionally went to higher education. An increasing share of the budget now goes to three areas: health care for the poor through Medicaid, child-welfare services and prisons.

"It's education or health care, and I would suggest the latter is winning in the political arena," says Nowlan, a former professor at Knox College in Galesburg. "The higher ed community should be thinking in new terms rather than trotting out something off the old podium calling for more state money."

That's where Wallace comes in. The ISU president argues the current funding system isn't working largely because it subsidizes students from families that can afford to pay a greater share of college costs. Instead of setting an arbitrary tuition benchmark, he wants to charge students based on their (and their families') ability to pay the full cost of obtaining a college education.

His plan envisions the affluent paying the bulk of higher tuition, which in turn would provide more financial aid to needy students. He noted that some 33,000 students who qualified for a state grant didn't get one last year because the Monetary Award Program (MAP) ran out of money. The state spent $201 million on 110,000 grants in fiscal 1993.

A portion of the money generated by tuition increases in Illinois goes back to students through financial aid. Pegging future increases to a sliding scale based on family income might free more money for student aid. Under Wallace's plan, some students would pay the full cost of instruction, some would pay a fraction and some would not pay any tuition at all.

A high-tuition policy also could help public colleges and universities make up for the steady drop in tax support per student during the past two decades. Higher education leaders can lament that decline all they want, Wallace says, but the response should be a more radical step in the direction they're already heading — toward higher tuition.

Different versions of a "soak-the-rich" plan for colleges and universities have been promoted unsuccessfully by others for years. Mere mention of dramatic tuition increases usually sends parents and lawmakers into sticker shock — a key drawback in the political arena.

Yet changing demographics within public.higher education suggest the state's low-tuition policy may be benefiting the rich while endangering access to college for low- and middle-income families.

For instance, about half of the students at Illinois State in 1990-91 came from families with incomes of $60,000 or more, according to a university report. Many of those students got a break on financing their education even though they failed to qualify for financial aid. That's because the state pays the difference between what students pay in tuition and what it costs the university to educate them, a subsidy of $2,800 per student, regardless of family income.

Federal student aid guidelines assumed that students with family incomes of $60,000 or more that year could afford to pay the full cost of attending ISU — $7,700 (a figure that reflects all costs, including room and board and student fees). But of the $54.5 million in state tuition subsidies allocated to the university, almost half went to students with family incomes exceeding $60,000.

The current funding system amounts to "welfare for the rich," says David Eisenman, a former member of the Illinois Student Assistance Commission and longtime proponent of a high-tuition policy. "Pew poor families can afford one cent of tuition," he says. "But so many rich families could write a check for the entire cost of sending their kid to a state school."

ISU's experience reflects what's going on across the nation. About half of the first-time, full-time freshmen attending selective-admissions public universities in 1990 had family incomes of more than $60,000, according to a study by the American College Testing Program. Fewer than one in four came from families earning less than $35,000.

Moreover, nearly $9 billion in tuition subsidies was granted to students nationwide who didn't qualify for financial aid during the 1986-87 school year, according to a report by the National Center for Education Statistics.

Says Nowlan: "In an era of extremely tight resources for state government, does it make sense to provide subsidies to people who have no need, especially when that policy may restrict access to young people whose needs are greater?"

Whether the state's funding policy for colleges and universities makes sense is one question. But changing it is a separate issue. Other higher education leaders predict Wallace's idea has no chance of getting through a skeptical General Assembly.

The University of Illinois in particular believes the proposal is a distasteful alternative. Leaders at the state's flagship university fear the more expensive "sticker price" envisioned in Wallace's proposal would create a public relations nightmare. It also might take the pressure off of lawmakers to provide adequate levels of state funding to public higher education.

"We shouldn't try to make public and private higher education costs the same," said Robert Resek, the U of I's vice president for academic affairs. "People in the state of Illinois believe their kids should have an opportunity to go to college for an affordable price. We continue to believe that education should be affordable for students whose family income levels are above the level that qualifies for financial assistance."

The U of I arguably is the most influential force in Springfield on higher education issues. So it's not surprising that the prevailing sentiment among lawmakers reflects their view. "I'd be very skeptical [of a high-tuition plan] and I think a lot of parents would be, too," says House Education Appropriations Committee Chairman Bill Edley, a Macomb Democrat. "To have front-end costs go up very dramatically, with prospect then of more financial aid, sounds good. But I think there would be a lot of people worried the financial aid wouldn't be there in the end."

U of I officials say higher education leaders should continue to press decision makers for increased state funding. At the same time, universities should establish annual tuition increases pegged to inflation. "As a result, parents and students can plan for college costs more effectively and quality can be sus-

May 1994/Illinois Issues/25

tained," a U of I policy document reads.

The U of I has its own institutional objectives at stake, too. The relatively low cost to attend the U of I, combined with its world-class reputation, has drawn more affluent students away from their traditional route through private institutions. A higher sticker price at the U of I might encourage those students to reconsider private universities.

"Some people within the higher education community have a radical suggestion regarding tuition policy," Resek says. "We have a more rational view."

Still, Wallace, ISU's president, says changes in higher education to meet the demands of future students won't happen without more money.

Higher education leaders publicly are jubilant over Gov. Jim Edgar's proposed 1994-95 budget for higher education, which includes the largest boost in state funding in years. The $1.65 billion spending plan is $86.4 million higher than last year's. But they say the funding increase, if approved, would do little to offset the past decline in state funding.

Public universities, Wallace says, have done a poor job selling citizens and decision-makers on the idea that tuition can be increased according to family wealth without adversely affecting low- and middle-income students.

At least one influential lawmaker is on board. Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman John Maitland, a Bloomington Republican, says increasing public university tuition for high-income families would "create a better balance between tuition and financial aid." It also could reduce pressure to raise taxes, he says.

However, Maitland warns, colleges and universities need to do a better job cutting costs and eliminating unnecessary or duplicate programs. "It's very tough to get people to come around on Wallace's idea," Maitland acknowledges. "But it could provide additional funding if you convince John Q. Public his money is being spent wisely."

The IBHE also is mulling the high-tuition policy. A panel studying ways to make college more affordable is scheduled to make recommendations to the full board in September, some of which will be passed on to the governor and lawmakers for consideration.

Jerry Blakemore, the panel chairman, says it's still too early to tell what those suggestions will be. "What makes this effort complicated is that it has so many implications on budgets, the competition between public and private institutions, and the role of community colleges," Blakemore says. "In the final analysis, the result should be the best policy to maximize our investment in the talent we are going to need in this state in the future."

Figure 1. Rise in tuition and fees for resident undergraduates

at Illinois public and private colleges and universities

|

Figure 2. Percent change since 1970 in public university tuition, state higher education general fund appropriation and consumer price index

|

The prospect of dramatic changes in the state's longstanding tuition policy may make some higher education leaders and decision-makers uncomfortable. But given Illinois' changing state budget priorities, public colleges and universities probably don't have a choice. Their alternative is to be satisfied with declining state tax support and a funding system stacked against their most needy students.

Michael Hawthorne is the Springfield bureau chief/or the Champaign Urbana News-Gazette.

26/May 1994/Illinois Issues