|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

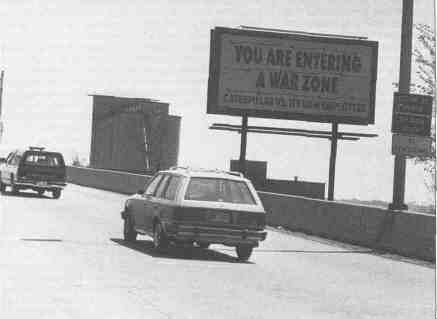

The billboard warning that you are entering a "War Zone" does not stand not outside Sarajevo, but rises above the steel railing of the new Bob Michel bridge connecting Peoria to Caterpillar's East Peoria complex. A battle between Caterpillar and the UAW has been raging since 1991. Like any war zone, the territory is devastated. Old brown brick factory buildings resemble the bombed out ruins in Sre-bonica but they are the results of obsolescence rather than mortar shells. New structures have been built, but they are located in other states. As the buildings shut down, the workers are shut out, and the union seems unable to help them. They have been working without a contract for the past two years, and they are wearing down. They see companies across the country laying off workers, and they want security. The community is tired of the war, too. Housing sales, retail businesses and development plans for future growth are closely tied to the economic health of Caterpillar's work force. If the union strikes for a long time, the economy will become tight. Only Caterpillar appears untouched by the war. The company announced a profit of $681 million for 1993 and is looking toward an even better year in 1994 with sales in Europe and Brazil stronger than expected. Earnings for the first quarter of 1994 passed all predictions, with a record profit of $192 million.

How has Caterpillar been able to make this comeback? It has introduced a vast new line of products, lowered production costs and modernized its manufacturing process. The company introduced over 40 new or improved products this past year. These included four new types of wheel loaders with roomier, more comfortable cabs (there's a place for a coffee cup and Thermos on the dash), a new giant hydraulic excavator that can perform two or more functions without slowing down and two new tillage tractors that meet stringent emissions requirements while providing fuel efficiency. As important, the company has reduced production costs. While part of this cost reduction has been the result of layoffs (worldwide employment has been cut by over 40 percent), far more has been involved. As many companies today are discovering, downsizing without other major changes in the corporate structure and in the way a company conducts business does not increase a company's profitability. To be successful, today's company must have the capability to engage in fast development cycles and flexible production, to provide quick response to consumer demands and to commit to lifelong quality. It requires that a company be customer- rather than product-driven. 22/June 1994/Illinois Issues

The company's reorganization and modernization program has consisted of: decentralizing; establishing teams of employees empowered to make decisions; automating, integrating, simplifying and consolidating the manufacturing process; downsizing the work force; and flattening the management hierarchy. Caterpillar has changed from a product-driven to a customer-driven organization by reorganizing into 13 profit centers based on customer needs. To decrease the time for development, many of these centers have been reorganized internally to follow a concurrent engineering model. In this model, design engineers and marketing and pricing staffs, instead of being housed in corporate headquarters, are located in plants where they work in teams with the manufacturing and assembly workers. Teaming enables both the production and pricing staffs to react to a design before the design engineers spend too much time on it. With teams empowered to make decisions about their respective areas of responsibility, the amount of time it takes to introduce a new product into the market is reduced considerably. Using teaming, the amount of time it took to design, test and build a new line of wheel loaders, for example, was approximately half that which it traditionally took to bring a product from concept to production. In addition to the changes in employee responsibilities and interaction, machinery and manufacturing processes have been modernized to bring the plants into the 21st century - with new processes as important as new technology. In fact, robots at Caterpillar did not prove to be much of a boon. In areas such as welding, robots could not do a satisfactory job. The welding done by humans was superior. Caterpillar modernized its plants with a program called P-WAF (Plant With A Future). P-WAP simplified the work flow and made the production process flexible. It also reduced material handling, decreased inventory and eliminated manufacturing space. Pierre Guerindon, credited with the success of P-WAF, compares the traditional manufacturing path to a plate of spaghetti as it winds up and down areas and in and out of buildings. Traditionally, in the manufacturing of gears, the milling, drilling and final assembly were done in one plant, while heat treating took place in another. Today gears are manufactured in a June 1994/Illinois lssues/23 single building. In the "old days," huge bins filled with parts waiting to be heat treated lined the walls and often crowded the aisles. Today, the parts are treated as needed and the line of bins has been reduced significantly. In the East Peoria plant, one million square feet of manufacturing space for producing gears has been eliminated.

As a result of its reorganization and modernization, Caterpillar reduced throughput time from 25 to six days (a 75 percent reduction), cut in-process inventories more than 60 percent and reduced salaried and management personnel by 18 percent. These changes have not come without pain. Nor are they without problems. The cost of changes is almost twice the original estimate, and they have taken longer to implement than expected. As the company has consolidated areas and reorganized its structure, managers have become disgruntled, being moved from section to section, often coming to work wondering whether they would have any section at all to manage. As layers of management have been flattened, the managers remaining found themselves required to take on new responsibilities. Some managers contend the hierarchy has been flattened too much and that eventually some layers will have to be replaced. P-WAF has not always run smoothly, either. Parts do not always arrive "just in time." And, because of low inventories, customers have not always been able to get machinery by the date promised. This is proving to be an increasing problem this year as the economy heats up and the company tries to meet more orders than expected. Despite these problems, Caterpillar's recent bottom line indicates the company is on the right track. With sales reaching an all-time high and costs cut dramatically, the company's profit margin once again looks good. The day after announcing its 1993 profit, Caterpillar's stock soared above $100 a share, the highest mark in its history. Caterpillar is situated to compete successfully in the international economy of the 21st century. It has recently signed agreements totalling $200 million with the Commonwealth of Independent States (the former Soviet Union) to supply tractors, pipelayers and off-highway trucks. Shortly after the U.S. Congress passed the North American Free Trade Agreement, which Caterpillar supported, the company received orders totalling $47.5 million from Mexico for Illinois-manufactured machines. Its outlook is rosy. There does not appear to be anything that could hold it back, including the UAW. On the surface the battle between the company and the union seems to be over pattern bargaining. In pattern bargaining, the union and a company within a particular industry sign an agreement which is used as the basis for agreements with other companies in that industry. In this case, the original agreement was signed between the UAW and John Deere. The union wants Caterpillar to sign a contract that reflects the union's contract with the John Deere Company, claiming the two companies are in the same industry. Caterpillar claims it should be considered as an individual entity, arguing that international competition makes it impossible for the company to agree to the union's terms. Beneath the rhetoric is a fight over the union's survival. The UAW is fighting to retain its hold over a declining membership (from about 24,000 in Local 974 in 1979 to slightly less than 8,000 today) and to maintain power in a significantly altered market. Caterpillar would like to see a more pliant union so that it can reduce high wage scales. The war is not a new one. It has been going on for some time, the most devastating battle occurring in 1982 when the union called a strike that lasted 205 days, the longest in the company's history. The strike saved Caterpillar from paying thousands upon thousands of dollars in unemployment insurance that would have cost the ailing company dearly. At the height of the strike, more than 50 percent of the work force was laid off in Illinois alone. While the strike had little effect on Caterpillar, it took its toll on the employees and the community. Many of the workers never totally made up the lost money, and a number of local businesses never regained the profits they had once made. Throughout the 1980s, as Caterpillar strove to pull out of the red, the union worked closely with the company. It was in the best interests of both to ensure the company's survival. The union recognized that modernization would require fewer workers, while Caterpillar understood the union's need to ensure jobs would remain in the area. The union and Caterpillar worked out an agreement whereby the company would maintain the number of jobs at about 8,900. For the next two contract periods the union refrained from any work stoppages related to negotiations, and contracts were settled relatively quickly and easily. That stopped in 1991. By that time Caterpillar had almost completed installing the major portion of P-WAF and had begun flattening out its management hierarchy. The company was already deeply involved in planning its next steps to maintain its edge in global competition. Cost reduction continued to remain at the top of its list. Because consolidation by reducing both space and labor had proved to be an effective method to decrease costs, the company was examining ways to achieve additional consolidation. The company wanted to further reduce the size of its work force as well as to reduce the cost of that force. To achieve this, it needed to be able to drop below the previously agreed upon 8,900 job level and to institute a two-tiered salary schedule. The union wouldn't buy it. When John Deere signed its agreement with the UAW, the union tried to use the agreement to force Caterpillar into Deere's pattern, which would have prevented a two-tiered system and saved local jobs. Caterpillar couldn't be coerced.

The ads were effective. In 1991, with the country in the middle of a recession, health care costs rising and workers being laid off in plants across the country, Caterpillar's offer of a six-year contract guaranteeing job security, health care coverage and a salary increase looked very good. As one union official conceded, "It's hard to get sympathy from a community where Illinois teachers are making an overall average of about $35,000, while our workers are making an average of $39,000." Many of the workers feel the same way. While outwardly they carry signs and wear T-shirts that proclaim the union forever, quietly they complain about absentee union leadership that rules from Detroit and is deaf to their needs. UAW secretary-treasurer Bill Casstevens has been warned that if a strike is called, only about half the membership will go out. Many of those who go will be the youngest members, the ones with the most to lose if the present contract is signed. It is they who will enter on the lower rungs of the two-tiered system. They will probably begin at $7 or $8 per hour. Employees at the North Carolina and Denver plants, which are not unionized, are making similar wages. According to Peoria Local 974 President Jerry Brown, these wages are so low that some workers in Denver are eligible for food stamps. In effect, Caterpillar's offer has already been accepted. When the union called off the last strike, it allowed workers to return to work under the company's final offer until a contract could be negotiated. With negotiations stalled, employees have been working under that offer for the last two years. June 1994/lllinois Issues/25 Cat has little motivation to negotiate further. The union called off the 1991 strike when the company threatened to replace the striking workers and was flooded with thousands of applications. Unless Congress passes a law prohibiting permanent replacement of strikers, the company will continue to hold the threat of replacement over the heads of its employees, virtually guaranteeing that a strike will not take place and leaving the union with no alternative except that of declaring an unfair labor practice (ULP) strike. In an unfair labor strike, a company is legally prevented from permanently replacing striking workers. The union is now conducting training sessions to acquaint its membership with procedures related to an unfair labor practice strike. In January it did a test run, calling a ULP strike that ran for three days. Almost 100 percent of the membership participated. A three-hour ULP strike was called by the union at the Decatur plant in April. Again, all union members participated. Several ULP strikes have been held since then in Pontiac, Ill., and York, Pa. A ULP strike appears to be the only weapon left for the union. Whether or not it can be effective in the long run remains to be seen.

Despite the threat of a lower standard of living for its members, the union has been unable to elicit the public's support as unions did in the 1930s and 1940s when John L. Lewis, Walter Reuther and George Meany waged war against companies that paid meager wages, provided no social benefits and forced employees to work in unsafe conditions. As one local union official recognized, it is difficult to get the community to support a strike when its teachers and police are not making as much as the union's hourly workers and when white-collar managers and independent business persons are not guaranteed the six years of employment that Cat is guaranteeing its employees.

26/June 1994/Illinois Issues to equalize the wage scales of the two countries and, thereby, reducing the potential ill effects of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement). Unions are also working to gain a foothold in such traditionally anti-union states as Missouri and North Carolina. Unions are also looking at new issues. The federal government's present emphasis on school-to-work partnerships offers unions an opportunity to become involved in improving technical education for the country's youths. But when Caterpillar, Illinois Central College and four school districts received a $100,000 state grant to provide training to 20 local students, the union refused to cooperate, warning that students should not be allowed to enter the present "difficult, potentially hazardous and strife-ridden work environment" that existed in the plants. A local union official commented, "At any other time, we would have welcomed the involvement." Caterpillar is not the only company that has recently been locked in a union battle. Peabody Coal and other companies are forcing unions to rethink the way they do business. With companies unable or unwilling to give large wage hikes or costly new benefits, several unions are negotiating contracts for longer than the traditional three-year period. The Diesel Workers Union recently negotiated an 11-year contract with Caterpillar's competitor, Cummins Engine Co. Workers were guaranteed employment until the year 2004, by which time they would all be ready for retirement, in exchange for concessions related to wages, retirement and seniority, one of the main points of contention between Caterpillar and the UAW (see box on previous page). When this magazine was going to press, negotiations between Caterpillar and the union appeared to be opening up. Early in May the union offered to renew negotiations without demanding pattern bargaining. Caterpillar responded by agreeing to remove its final offer and negotiate on the issues. Then both parties flexed their muscles. In an apparent effort to circumvent the UAW's national leadership, the company proposed that bargaining be limited to a specific time period and that, at the end of that period, whatever proposal was on the table should be taken directly to the members for a vote. The union decried the tactic. A number of workers protested by carrying to their work stations balloons with union slogans. Supervisors suspended the workers, prompting more than 7,500 workers in Local 974 in central Illinois to walk off their jobs May 16 in an unfair labor practice strike. But within a few days, following additional public muscle flexing, Caterpillar reinstated the suspended workers, and the UAW called off the strike. Caterpillar, however, apparently had had enough of the string of brief strikes — eight in the past six months. Four days after the workers returned, Cat announced it would no longer guarantee that workers could return to their jobs after walking off. Citing interference with customers touring facilities and with non-union employees, the company warned that union members do not have the right to participate in disruptive behavior in the workplace. Until now, Caterpillar has been in control. But pressures on both parties to reach a settlement are building. The unexpected increase in worldwide sales has caused the company to step up production. With sales up and inventory down, the company needs a dependable workforce to keep its product reaching the market on time. While the intermittent ULP strikes are brief, they're also disruptive. The union, meanwhile, may have made its offer to return to the bargaining table as a show of good will, as it claimed. It may also have made the offer in an attempt to sign a contract with Caterpillar before entering into upcoming contract negotiations with John Deere, or in an effort to prevent further erosion of a dwindling and disenchanted membership. With both parties finally communicating and with forces in both parties creating pressure for a settlement, there's a slight glimmer on the horizon that a new contract eventually will be signed. Caterpillar has not only shown it can survive. It has proven it can prosper. Whether Illinois will be able to share its good fortune, however, is questionable. Caterpillar has found more conducive environments to sustain its modern, globally competitive business. Several divisions have already been relocated outside Illinois. Its financial division was moved from Peo-ria to Tennessee in 1991 and its Advanced Technology Compaction Group followed within three years. While Caterpillar officials have reaffirmed their commitment to central Illinois, they will not say whether they have plans for future relocations. They point, however, to the considerable investment they have in their three major products — track-type tractors in East Peoria, wheel loaders and excavators in Aurora, and haulers and motor graders in Decatur — as evidence of their intentions to remain here. Their recent announcement of a $15 million investment to complete the Peoria Southtown facility for management personnel further supports their contention. However, they continue to eliminate jobs, sometimes outsourc-ing work to other states. According to UAW President Jerry Brown, Caterpillar originally agreed to 8,900 jobs in East Peoria. Today, that number has been reduced to 8,000. While it appears Cat plans to remain in central Illinois, it does not appear to have any plans to locate new plants here. The company has opened several new plants (two in North Carolina, one in Missouri, and one slated for South Carolina) but none in Illinois. Until the 1981 recession, what had been good for Caterpillar had been good for central Illinois. But in the 1980s it became apparent that central Illinois could no longer count on Caterpillar. The region learned its lesson and diversified its industry. As a result, central Illinois was hit less by the recession of the 1990s than either U.S. coast. As Caterpillar prospers in an adapting central Illinois economy, it remains to be seen whether the union will make the necessary adaptations to flourish in the next century. Carolyn Boiarsky is a freelance writer in Peoria. June 1994/Illinois Issues/27

|