|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By ROBERT DAVIS Running Chicago

When it comes to style, Chicago mayors run the gamut After all, everything in life is your presentation — Mayor Richard J. Daley Maybe, just maybe, Richard J. Daley, who had been toiling in the relatively obscure post of Cook County clerk as a loyal but colorless Democratic Party functionary, was uncomfortable when he took over City Hall's Fifth Floor office as Chicago's mayor in 1955. Few of the insiders who were there that year are still around to remember what the loyal Son of Bridgeport was like when he moved to the forefront of Democratic (and national) politics, answering his party's call to dump the increasingly independent Martin Kennelly and restore the powerful, patronage-rich office to the greedy hands of the vaunted Cook County Democratic machine. More, though, remember the Richard J. Daley of the 1960s and 1970s, the man with the infectious giggle, the troubling scowl, the fractured syntax, the ready wit (usually at the expense of others), and the seemingly natural comfort with which he occupied the office for 21 years. Unlike no other person in Chicago's rich political history, Richard J. Daley defined the office of Chicago mayor. As often as not, he was referred to as "The Boss" or "Hizzoner," and when someone said "Da Mare," in Daley's own South Side patois, no one ever asked which city was being discussed. In the 18 years since his death, however, the coveted office has changed hands an amazing five times, or six, if one counts the truncated days-long regime of Cook County Clerk David Orr, who served as acting mayor during the tumultuous days following the death of Mayor Harold Washington. Each of those who have held the title since Richard J. Daley died of a heart attack moments after one of his pre-Christmas public events on December 20,1976, has tried to stamp his or her own definition of style on the job, with stark and varying results. Richard J. Daley's love of government was surpassed only by his love of the public events that accompanied the day-to-day operations. He loved the national monicker of "The City That Works," but he also wanted it to be "The City That Plays." One of the first things globe-circling astronauts received after returning to Earth in those space-happy days was an invitation to come to Chicago where a huge, tickertape parade could be guaranteed. Chicago crowds loved parades, especially when they were embellished with Daley's obedient 42,000-member work force, which would gladly line a downtown city street to cheer the conquering heroes when it involved a reprieve from their work duties. In 1976, Daley's last year in office, the United States of America was having a big birthday party for itself, and, to honor the country in its 200th year, heads of state, kings and queens, and big-name politicians always came to Chicago. Although professional cynics, especially those in the media, pointed out the incongruity of Daley's striding alongside foreign kings, reviewing a group of military personnel from Fort Sheridan in the Civic Center Plaza, the mayor loved it.

He loved it as much as he loved the stream of celebrities and movie stars who made pilgrimages to his office whenever they came to town. Former Ald. Roman Pucinski (41st) had brought pop singer Bobby Vinton to Daley's office one time to perform at a Polish organization function. At Pucinski's urging, Daley held a news conference with Vinton in his office, and the ebullient singer, who was carving out a second career for himself as a Polish idol, convinced Daley to join him in a chorus of a Polish pop tune. The resulting pictures and sound made all of the TV shows. Every celebrity who made a courtesy call to Daley was trotted out before the cameras in Daley's press conference room to engage in sprightly, although sometimes awkward chatter with Daley and the news media. No one refused. Press-hating Frank Sinatra participated in one of his rare news conferences with Daley; Perry Como, John Wayne, Bob Hope, they all came and stood at Daley's side. When Michael Bilandic took over in 1977, he tried in vain to emulate his mentor's public style. Bilandic had been the handpicked alderman of Daley's own South Side 11th Ward, 22/February 1995/lllinols Issues the traditional birthplace of Chicago mayors for decades, and, as chairman of the all-important City Council Finance Committee, he was the logical successor when Daley died. Bilandic had studied at the side of Daley, watching the man engage in a daily whirlwind of social and political rounds, in addition to maintaining a hammerlock on all governmental activities. But Bilandic never quite fit in with the Irish Bridgeport crowd. A slow-talking, detail-obsessed Croatian business lawyer, Bilandic's attempts to schmooze with the stars seemed awkward, especially in comparison to the giggly Daley. He once tried to hold a press availability with black soul singer Aretha Franklin, but it was a masterpiece of discomfort as a group of disgruntled African Americans held a noisy protest outside the mayor's office. Still, to his credit, Bilandic tried, answering the luncheon bell virtually every day he was in office, going to whatever he was invited to, and droning on in a familiar speech that was highlighted by his disclosure that the City of Chicago's bond interest rates were highly favorable. But Bilandic also invented ChicagoFest, a weeklong food and music festival that reintroduced the sagging Navy Pier along the city's lakefront to hundreds of thousands of Chicagoans or former Chicagoans who had fled to the suburbs. Bilandic and his socialite wife, Heather, gamely went to Navy Pier every day during the first ChicagoFest. Bilandic's public image problems were never more boldly magnified, though, than during the now legendary Blizzard of '79. That snowstorm was actually a seemingly nonstop series of blizzards that began on December 31, 1978, and kept coming until February 28, 1979, when the sun erupted, melting the snow and allowing disgruntled Chicago voters to flock to the polls to vote for political outcast Jane Byrne. Byrne's public style was her strongest point; stronger, most agree, than her grasp of government, which some said she ruled with a whim of iron. In her early years, Chicagoans seemed to treat Byrne as Chicago's number one spectator sport. The city's athletic teams at the time were uniformly dreadful, so Byrne's "revolving door" brand of governance was a welcome respite from the dirgelike City Hall atmosphere during Bilandic's days. She first tried to kill Bilandic's ChicagoFest, one of the few happy memories city residents had of Bilandic's brief regime, but when a public uproar broke out, she characteristically did a 180-degree turn and adopted the event as her very own. In fact,

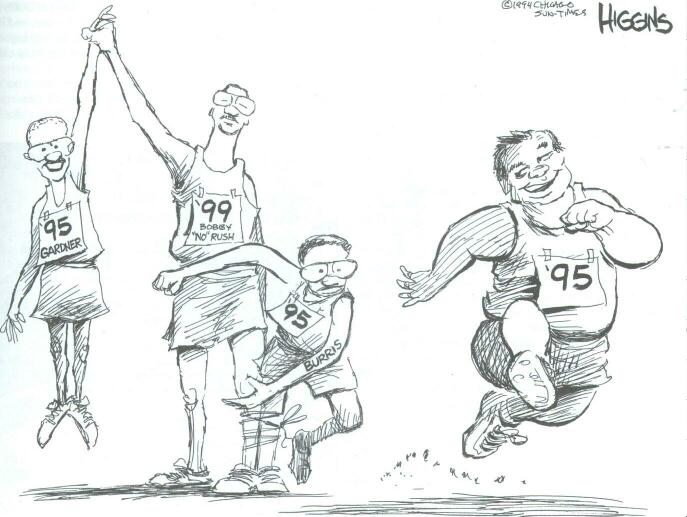

February 1995/lllinois Issues/23

she embraced ChicagoFest so passionately that she ordered her Special Events office to come up with spectacles like it. They produced A Taste of Chicago, Loop Alive, AutumnFest and dozens of smaller neighborhood festivals throughout the city. Byrne went to most of them, often breaking out into song on the stage, wearing funny hats, sampling, but only daintily, the food. She donned a black fedora and dark sunglasses to pose with The Blues Brothers, John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd, while they made a movie here. They, in turn, agreed to open up one night of ChicagoFest when the main act cancelled out. But being mayor still involves running a sprawling government and answering more basic political needs, and at the end of Byrne's four-year run as mayor, Chicago's voters, including a crusade-like march from the African-American communities, installed U.S. Rep. Harold Washington as the city's first black mayor. In public, Harold Washington, big and garrulous, almost made Byrne look like a wallflower. Although he killed ChicagoFest and gave only lukewarm support to Byrne's doomed dream of staging the 1992 World's Fair in Chicago, Washington loved a good party. He went everywhere. He kissed every lady in sight. He ate whatever was handed to him. He picked people out of the crowd and yelled out their names. He excoriated individual reporters, much to'their delight at being singled out by such a public figure. And he, too, sang, in a loud but terrible voice. Harold Washington didn't seem to care. If his "Chicago, That Toddling Town," didn't toddle as melodically as Frank Sinatra's, it was louder and more enthusiastic, Harold Washington was a man of great appetities, and some say that probably killed him. He reportedly weighed in at over 270 pounds when he slumped over and died at his City Hall desk the day before Thanksgiving in 1987. His governmental accomplishments as mayor are debated to this day, but no one denies that he lent a stylish panache to the office during his five years there. David Orr served only long enough to warrant having his photograph installed on the North Wall of the mayor's reception area in City Hall, a conceit insisted upon by the Lakefront Liberal that still draws mutters from critics. Washington's real successor was Eugene Sawyer, a little-known and relatively undistinguished South Side product of the regular Democratic machine, whose year in office seemed to be marked by no style at all. Chosen as a compromise by the City Council's anti-Washington white forces, Sawyer spent his year in office not welcome in his own community and not much respected elsewhere. His public and private personna was so low-key he was tagged with the nickname "Mumbles." That was not as disrespectful as it sounds. One television news program one night ran subtitles across the bottom of its screen during a film clip of Sawyer, translating the words he was muttering into the microphone. And now we have Mayor Richard M. Daley. Few remember personally what Richard J. Daley was like in his first years in office. Most memories of the first Mayor Daley are of his final years, bantering with presidents and laughing at his own jokes. Daley the son is now in his formative years. Most figure he will win another term in April, and many figure it will be his last. Changing demographics are certainly part of it, but also Daley's feel for the office is as different from his father's as it is from the five other people who have held the title since his father's death. Richard M. Daley loves sitting in the Fifth Floor office, scrutinizing the books, grilling department heads, making deals with other politicians, and chewing on an unlit cigar in a cubbyhole of a sanctuary behind his official office. Richard M. Daley loathes the trappings of the job and does a terrible job of concealing that loathing. While his father loved City Council meetings and the often volatile parliamentary gameplaying they involved, Daley fidgets like a kid in a church pew, often leaving the chambers for long periods while he chats with people in the anteroom. He has a lopsided grin he snaps on when posing for pictures with groups or individuals, but has a habit of turning away when the shutter clicks. Daley likes to walk to and from events in downtown Chicago, and his pedestrian journeys are generally uneventful, with few people waving or even acknowledging who he is. Similar walks by Byrne or Washington were like campaign appearances, all shouts and handclasps and banterings. Daley uses the walks not as a chance to meet the public, but as a way to get from one place to another. But, again, few know what the early Richard J. Daley was like. If his son chooses to stay in office for 21 years, and if the people choose him to do so, he may one day be singing songs at news conferences or slurping down Salvation Army chili at a photo opportunity as his father once did. Every mayor in the last 40 years has brought his or her style to the office, but, in the end, the office brings its own style to its occupant, as well. The secret is to stay in that office long enough. *

24/February 1995/Illinois Issues |

|

|