|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By JAMES KROHE JR.

What to do with troubled kids

Today's social ferment echoes another era of Illinois history -- The '90s are a tough time to be a kid in Illinois — the 1890s that is. Nothing pressed more painfully on the still-tender social conscience of Illinois' 19th century bourgeoisie than the plight of children who in their immaturity chose to be born poor or deformed, or picked abusive parents. These unfortunates were visited by all the horrors familiar to us from today's headlines, plus a few we have forgotten in the intervening century, such as sweatshop labor and endemic disease.

The word "progressive" these days is usually understood to mean "reform," although years of progressive school reforms left few Illinois kids knowing enough history to understand why. The 20 years or so that ended with World War I was a time of social ferment in Illinois. A newly ascendant middle-class rose in revolt — politely — against inept government, corrupt elections, scandalous public sanitation and barbaric work conditions. Progressive-era reformers such as Jane Addams also asked basic questions about who ought to care for children whose parents were unable or unwilling to care for them, and how. The answers they came up with constitute virtually the whole of today's child welfare orthodoxy from pedagogy to playgrounds and from infant nutrition to immunization. Today's state of Illinois child welfare institutions also date from the turn of the century, at least in concept. (Some, like a centralized Department of Children and Family Services, had to wait a half-century to be implemented.) The debate over child welfare as it was phrased by progressive reformers 100 years ago — institutionalization versus subsidized home care for the dependent and the handicapped, for example, or incarceration versus rehabilitation for delinquents — set the terms in which those issues have been argued in Illinois for a century. And re-argued. The 1990s are another time of social ferment stirred by Illinois children. In Poor Relations, her fine new history of Illinois' child welfare programs, Joan Gittens observes that Americans in the 1990s feel "a sense of crisis very similar to that experienced by their progressive forbears." As happened a century ago, crisis excites both reforming passion and reactionary zeal. The result is a sense of confusion very similar to that experienced by our progressive forbears. The policy questions being asked today are just as basic, and just as hard, as those the progressives asked in the 1890s. Indeed, as Gittens makes clear, they are the same questions. The difference is that today the questions have names: Joseph Wallace. Baby Richard. Richard Sandifer. Eric Morse. The Keystone kids. The parallels are plausible, not perfect. Child welfare controversies in both eras do derive, however, from substantially similar social conditions. Economic instability, rapid population shifts, feminist challenges to social verities, endemic fear of the city and its contagions, social breakdown among inner-city subcultures — all were as familiar to 1890s Illinoisans as they are to us. Likewise, the predicament of Illinois' ill-favored young people has again stirred grassroots involvement. An anxious (and mainly female) middle class has aroused itself to do battle with incompetent bureaucrats, cowardly politicians and an indifferent public. One proof of a revivified Progressivism was the founding in 1987 of Voices for Illinois Children, in which what Gittens calls the "amateur sentiment" of the 19th century volunteer animates some very professional fact-based advocacy techniques. Quiescent Progressive-era institutions and movements, from the Parent-Teacher Association to Montessori schools, have asserted themselves anew. State institutions also are reverting (often unknowingly) to the ideals of their founders. Instruction in parenting — a mainstay of today's family preservation interventions — was offered by Illinois' pioneer mothers' pension program in 1911. A new community-based service strategy announced by the Department of Children and Family Services in January looks a lot like the settlement house remodeled in 1990s style, with its emphasis on local resources, neighborhood self-help and one-stop shopping for social services. The new chief judge of the Cook County Circuit Court, Donald O'Connell, is trying to move the state's most impor-

March 1995/Illinois Issues/19

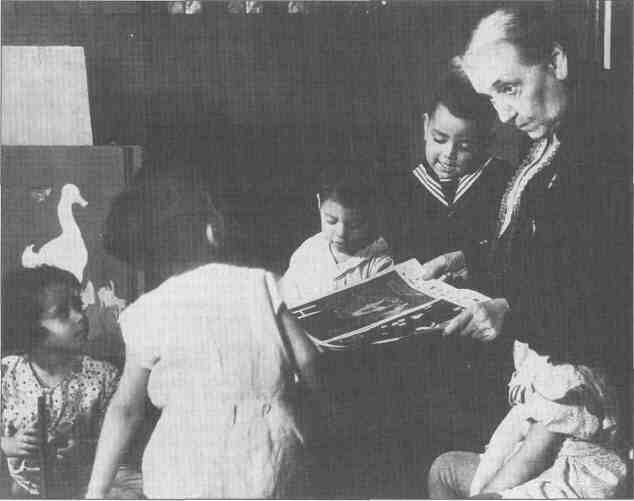

Photo courtesy of Illinois State Historical Library, Springfield Progressive-era reformer Jane Addams asked basic questions about who ought to care for children whose parents were unable or unwilling to care for them. The 1990s are another time of social ferment stirred by Illinois children. As happened a century ago, crisis excites both reforming passion and reactionary zeal. And a confusion similar to that experienced by 19th century progressives.

tant Juvenile Court forward by moving it backward, toward the concept of the court's founding 1899 act. The court is a landmark in progressive child welfare history, and as the first such court in the nation was much imitated by other states that sought to bring compassion and flexibility to their dealings with troubled kids. Alas, reforms of the reform in the 1920s and again in the 1960s improved due process guarantees at the cost of making court proceedings more adversarial and cumbersome. A century of determined improvement thus left Illinois with a court that combined an eager interventionism that sweeps thousands of children into the court's protection and a decision-making process so bogged down by "overlawyered" procedures that they stay there. O'Connell has revamped the court administration, increased the number of juvenile court judges to 29 to speed handling of 33,000 pending abuse and neglect cases, and streamlined procedures to reduce the court's backlog of 400 to 500 adoption cases. Also in place are new hearing officers authorized by the Edgar administration a year ago; their purpose is to de-lawyer proceedings and refocus attention on the best interests of the children involved. The enthusiasm for century-old progressive ideals shown by the Juvenile Court in Chicago is not universal. In 100 years Illinois has evolved a child welfare bureaucracy capable of offending nearly every scruple from religious separatism, racial exclusivism and philosophical distaste for centralized state authority to cheapskate-ism and resentment of the sort of expert that the progressives enshrined as the arbiters of children's needs. At the moment the prevailing winds of change are blowing from the political right. In February the Republicans in the General Assembly proposed changes in the state's Aid to Families with Dependent Children program. AFDC is Illinois' largest children's program, and the GOP's changes mirror those proposed by the new Republican Congress. Among other things the proposed regulations (for the moment subject to approval by federal authorities) would require teen-age mothers to stay in school, live at home and forgo further births or lose their benefits. Also, family benefits would be made conditional upon children attending school, and cash benefits would 20/March 1995/Illinois Issues be limited for children whose paternity is not established. Were Mr. Gingrich, the Republicans' leader in the U.S. House, a better historian, he might be aware that Illinois' dependent families were subject to far more draconian strictures in pre-progressive days. (Mothers who surrendered their infants to county poorhouses, for example, were expected also to surrender their rights to the children.) Those strictures had little apparent improving effect on the behavior of dependent families, a failure that was behind the progressives' search for alternatives. Today's AFDC derived from an experimental mothers' pensions program adopted by Illinois in 1911. The mothers' pension was intended to enable lone mothers with children to keep their kids at home — and out of expensive state institutions such as orphanages. As Gittens' account makes clear, there has been no genuinely new child welfare idea in Illinois for more than a century, only new versions of old programs whose failure has been forgotten. For example, news stories about 11-year-old gang hitmen in Chicago have generated enough public heat to make lawmakers in Springfield sweat. Proposals have been seriously advanced to further lower the age of criminal responsibility (from 13) in cases of juveniles accused of certain serious crimes. If the public is protected any more than that, children as young as 10 years may be tried as adults in Illinois. That is the age of criminal adulthood the General Assembly set in 1827, before Illinois decided (for the first time) that treating kids like grownup villains puts a stop to their childhoods but has very little effect on villainy. There is one aspect of the progressive approach that continues to enjoy support across the political spectrum. That is the use of state authority to intervene in the lives of families on behalf of children. Compulsory schooling laws, for example, overrode centuries of common law that upheld the right of fathers to tend to kids' schooling. That aspect of the progressive credo often confuses more recent critics. Their pro-state, pro-social service bent is today usually thought characteristic of liberals, yet their countenancing of coercion violates liberal notions of individual rights. Indeed, it was 1960s liberals who won important due process protections for people victimized by progressive-style do-gooderism that in incompetent or arrogant hands had turned destructive both of families involved in child custody cases and of arrested juveniles. However liberal their means, progressive reformers at the turn of the century worked for socially conservative ends. They hoped that intervention could relieve the threat from an unsocialized, disease-ridden and violent underclass whose children menaced property and propriety. Their interventionist stance was denounced by 1960s revisionists who saw the progressives as cultural imperialists, even racists whose real object was the subjugation of marginal peoples who ranked high on the roster of middle-class bugaboos. These included the poor (who even then were disproportionately black) and peasant (and mainly Catholic) immigrants. The enthusiasm of the political right for state intervention — from orphanages to compulsory contraceptive implants for welfare moms — is especially remarkable, considering their philosophical distaste for state action in all other realms. Today, the state is taking more kids into custody than ever, in spite of the fact that the family is officially extolled as society's essential unit. The contradiction is more apparent than real. The family is generally seen as society's surrogate in the lives of children. A family that fails to socialize its young forfeits society's protections. Using the state as a tool to socialize the lower classes may be one of the few state powers the right sees as legitimate. The left offers scant protections against this kind of pre-emptive social control, and in fact abets it by championing the rights of the child against his or her family. The liberals endorse coercion for the good of the child; the conservatives do the same for the good of society. Thus has the helping hand of the progressives been armed with police power for a century in Illinois. The child welfare reformers of the 1890s could not move mountains. (Although they did move rivers; the reversal of the Chicago River in 1900 was prompted in large part by the high infant death rate from dirty water.) Nonetheless, progressive ideas and ideals still dominate child welfare policy in Illinois. The principle of state intervention is unchallenged, however much it has been constrained, and for all the jabber about reforming the system of cash assistance to mothers with children, no one is talking seriously about abandoning it. How are we to explain the enduring success of progressive reforms in spite of their having been, in Gittens' phrase, "plucked to pieces" over the past hundred years? To their proponents, the answer is simple — they are right — but more worldly observers may point to the way progressivism wraps expediency in humanitarianism. Mothers' pensions kept babies at home with mom — and saved the state a lot of money on orphanages. Innovations meant to benefit kids proved even more beneficial to the adults who ran the system; probation for juvenile offenders was meant to keep them out of jails where they did not belong, but probation also is a great way to keep kids out of jails that don't have room for them. In October, the chairman of the Citizens Committee on the Juvenile Court mounted the soapbox to restate the progressive case regarding juvenile criminals. There are no bad kids, he said in effect, just disturbed kids who need help, or confused kids who lack proper adult supervision. It is impossible to say how many Illinoisans agree with that view, but it seems likely that ever fewer do today than agreed 100 years ago. The notion has never gotten a proper test, because in nearly 100 years Illinois has never done very well at providing troubled kids with adult supervision. Unfortunately, the state hasn't done very well at providing jails for kids either — which brings us to what looks like a truth about Progressive-era reforms. They were adopted then, and largely survive now, not because there is a consensus in their favor but because no one has had any better ideas. * James Krohe Jr., formerly of Springfield and Oak Park, III., is a free-lance writer living in Portland, Ore. When still an Illinoisan, he undertook an exhaustive study of child welfare services for the Taxpayers' Federation of Illinois.

March 1995/Illinois Issues/21

|

|

|