|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By TOBY ECKERT

State justices take the role of Solomon

The case shows the tension between the No contemporary Illinois Supreme Court decision has stirred as much emotion as the Baby Richard case. It is a saga of truly biblical proportions, with the justices cast in the unenviable role of Solomon. The fate of a 3-year-old boy hangs in Justice's scales. The motivations of two sets of apparently loving parents — one biological, one adoptive — have been scrutinized through cynical lenses. A judge has been repeatedly flayed by the media. But underlying the public tempest is the unsentimental word of law. These two worlds, the legal and the emotional, often clash, with no less import than the Baby Richard case. Dozens of people are condemned to death by the same system every year. It expands, and just as often erodes, a woman's right to determine the destiny of her own body. It interprets the abstract idea of liberty that is at the core of our national being. Yet, for all its importance, the legal system is the arm of our democracy that is least understood by the public. Its ways are Byzantine and its proclamations are handed down in language and logic that often are alien to common citizens. This is the story beneath the story of Baby Richard. The story began on March 16, 1991, when a Czechoslovakian immigrant, Daniela Janikova, gave birth to a son in a Chicago-area hospital. Four days later, the boy was in the home of adoptive parents, known by the common legal aliases John and Jane Doe. How the child ended up in this situation is a tale worthy of a soap opera. The father, Otakar Kirchner, was in his native Czechoslovakia, visiting his ailing grandmother, when the child was born. A meddling relative called Janikova, his fiancee, and informed her, falsely, that Kirchner had reconciled with a previous sweetheart. When Kirchner returned to the United States, Janikova told him the child was dead and the wedding was off. According to his own accounts, Kirchner never accepted Janikova's story. He searched through her garbage, looking for discarded diapers, and pored over birth and death records. Others have painted a different picture of Kirchner, that of a man who abandoned his wife on the eve of labor and showed little interest in the fate of his offspring. Whatever the case, Kirchner learned 57 days after the fact that he was a father and, on May 18, began the process of trying to take custody of Baby Richard. Two courts thwarted Kirchner, saying he was an "unfit par-

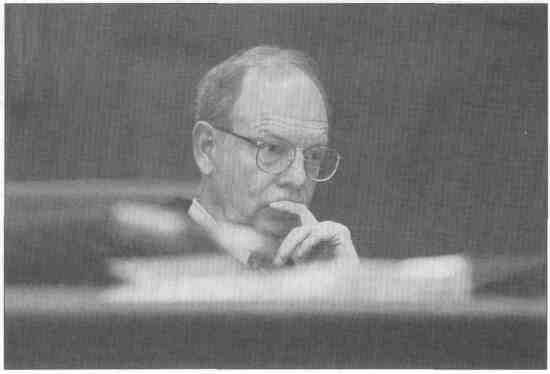

Photo by AP/Wide World Photos

Illinois Supreme Court Justice James D. Heiple listens to arguments in the Baby Richard custody case January 25 22/March 199 5/lllinois Issues ent" because he had failed to show a "reasonable degree of interest" in the boy during the first 30 days of his life. That is one standard by which Illinois law measures a parent's worth. But Kirchner refused to give up his fight, even as Baby Richard was growing in size and nurturing a child's first awareness of belonging to a family. On June 16, 1994, the Illinois Supreme Court gave Kirchner what he wanted. In an opinion that ran barely more than two pages, the court set in motion the process of taking a 3-year-old child from the only parents he had ever known. In writing the court's opinion. Justice James D. Heiple said the 30-day interest standard was improperly applied to Kirchner. "In fact, he made various attempts to locate the child, all of which were either frustrated or blocked by the actions of the mother," Heiple wrote. "Under the circumstances, the father had no opportunity to discharge any familial duty." The decision of the seven-member court was unanimous, though three justices, feeling Heiple had been too abrupt, filed a lengthier concurring opinion. Both opinions accused the Does of aiding, or at least acquiescing to Janikova's concealment of Baby Richard from Kirchner. The court was reflecting a long legal tradition of making the rights of biological parents paramount. Yet, society's view of such matters has evolved at a much faster rate than the court's. Tales of children returned to abusive parents by the state, only to suffer torture and death, have convinced many people that when there is any question of parental soundness, keeping a child from her or his biological family is in the child's best interest. Moreover, the Baby Richard decision was handed down less than a year after a child in a very similar situation, Baby Jessica, was literally wrenched from adoptive parents in Michigan and spirited to the home of her biological parents in Iowa. Televised images of the highly emotional scene still were shining in the minds of many Illinoisans when the court ruled on Baby Richard. The decision also galvanized the news media, especially Chicago Tribune columnist Bob Greene, a frequent defender of troubled youth. In Greene's eyes, the court was doing the work of evil. And he has demonized Heiple. Others have followed suit, notably Chicago television personality Walter Jacobson, who called Heiple "dangerous" and publicized the judge's home telephone number, with predictable results. Heiple is a tempting and easy target. A profoundly conservative jurist from downstate Pekin, he is the embodiment of what populists and "small-d" democrats hate about the judiciary — aloof, often arrogant and virtually unaccountable. Some of his written opinions are sharp, filled with invective and personal attacks on lawyers and other judges. Heiple once neatly summed up his judicial philosophy thus: "The justices of the [U.S.] Supreme Court have, on the whole, been too willing to impose their personal views of what society should be on the Constitution. Too often, they have been willing to deviate from the precept that we are a government of laws and not a government of men." One would be hard pressed to find a neater statement of judicial alienation from the ordinary citizen.

Heiple didn't improve his public image with his second written opinion in the Baby Richard case, in which he rejected petitions for a rehearing and answered his critics, including Gov. Jim Edgar. Heiple on Greene: "Greene brings to bear the tools of the demagogue, namely, incomplete information, falsity, half-truths, character assassination and spurious argumentation. ...These are acts of journalistic terrorism." Heiple on Edgar and the legislature, which rushed through adoption law changes in a bid to reverse the court's decision: "Both the governor and the members of the General Assembly who supported this bill might be well advised to return to the classroom and take up Civics 101. The governor, for his part, has no understanding of this case and no interest either public or private in its outcome. The legislature is not given the authority to decide private disputes between litigants. Neither does it sit as a super court to review unpopular decisions of the Supreme Court." Heiple's tirade was highly unprofessional, and in the eyes of many lawyers and judges it sullied the reputation of the entire court. Nonetheless, his underlying message is correct. Legal matters should not be decided on emotion or influenced by public passions. It is a judge's job to interpret and apply laws as they were written by legislators, not to make exceptions on a case-by-case basis. And there is good reason to zealously guard the separation of powers, which creates checks and balances and keeps the governor and the legislature from meddling in the court's business. Yet the enduring image of the case will not be how it laid bare the tensions between the law and the impulses of humanity. It will be the image of a child whose entire life will be rearranged during his most impressionable years, with all the uncertainties and ramifications for his future that such a change imports. In that rests the tragedy of the case. Because, ultimately, the system did fail Baby Richard, even if he lives happily ever after. Everyone is entitled to swift justice, but it is particularly pressing when a child is involved. Yet it took the original trial court a full year after Baby Richard was born to rule on his case. The appeals court took another year and the Supreme Court yet another. When the case started in 1991, there was an infant whose notions of family, love and loyalty were just beginning to form. Now there is a lad who may experience all the painful awareness of separation, without the benefit of understanding. * Toby Eckert is a Statehouse correspondent for the Peoria Journal Star. March 1995/Illinois Issues/23 |

|

|