|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By GINGER ORR

Giving kids alternatives to gangs

Walter Smith lost half his football team to gangs. Twelve-year-old Robert Turner sat on top of a picnic table in the middle of Frederick Douglass park, his chin resting in his hands, his elbows propped on dark, scabbed knees. A North Carolina blue and white baseball cap was pushed forward over his eyes. He was waiting for the rest of his teammates to show up for the day's football practice. Gradually they arrived, coming from all directions across the park to gather at the blacktop basketball court in the middle. Some had their purple jerseys slung over their shoulders. All carried white helmets with the purple Warriors emblem plastered on the side. There were only 11 boys playing on the Pee Wee football team at Sunday's game. Normally there were 13, but Rodney would be out of town that weekend and Clifford broke his pinkie finger last week. Both of them showed up for practice anyway. A whistle cut through the air. "C'mon fellas," their coach, Walter Smith, called out to the scattered boys. Within seconds the middle school-aged boys clustered around the imposing 45-year-old man who stood a good two feet over them. The park fell silent as Smith told them they were short two players. This meant every one had to play the whole game. If anyone got hurt or kicked out, that was it. Be careful, he warned them before barking out orders to lap the large one-block park — the standard start of practice. The boys took off, the taller ones quickly taking the lead, their long, thin legs looking like they would snap with each step in their clunky, over-sized leather high-tops. Off to the side, members of a local gang crowded around the basketball hoop and watched them. Robert lives in a neighborhood where gangs have stolen the sense of community away from its residents, and Walter Smith is fighting to get it back. His sports teams give kids like Robert an alternative to gangs and a safe haven from the streets. In a neighborhood beset with poverty, growing fear and desperation, Smith attempts to counter the lure of gangs with opportunities of his own. It all started with football. For two years, the director of the Frederick Douglass Center had wanted to form a football team for the black youth in northeast Champaign. The Champaign Park District didn't offer a program. So, like many of his other projects. Smith initiated the idea on his own. For most of the boys it was their first chance to participate in anything more than a neighborhood pick-up game. They had never worn uniforms or shoulder pads and never had a pair of cleats or a real coach. Growing up in the public housing around the Douglass Center, 11-year-olds went home to empty apartments with little supervision and nothing to do but hang on the streets. The only teamwork they had ever known came from the gangs that ruled their neighborhood — the Gangster Disciples and the Vice Lords who had come down from Chicago to recruit middle schoolers because they were less likely to get punished in the juvenile court system. The gangs use force. Smith said. "They say to some of them if they don't sell these drugs, they won't let them on the bus, they'll beat them up, they won't let them go to school. They use school as an enforcer to get to the kids. You can't walk way over there to Robeson School or Bottenfield or Westview. That's a long ways for these kids to be walking. That's something we've got to work on."

Officer Gene Stephens, one of two community police officers who walks the streets around Douglass, estimates that 85 percent of the high school-aged black males and 50 percent of the middle schoolers in northeast Champaign are involved with gangs in some way, either as a runner, lookout or drug dealer. Stephens said he makes an average of two or three arrests a day for fights, weapons or drug activity related to the gangs. The gangs may control the four public housing developments bordering the one-block park, but the Douglass Center has been unofficially declared a neutral zone. The center's new-looking, brick building with tall, narrow windows lined up across its front looks like an oasis surrounded by the tired rows of low-rise frame apartments that cluster in groups around vacant concrete courtyards. Grade school children

April 1995/Illinois Issues/27

crowd onto the Douglass playground after dinner, unsupervised. The elderly stop by to pick up free loaves of fresh bread donated by a local bakery. Pee Wee football practices every evening in the park surrounding the Center. Even gang members come for Open Gym Nights, but once they step inside, their hats come off and they are just teenage boys who want to play basketball. Whatever gang activity occurs, happens off the center's property. One measure of Smith's success is the fact that the gangs clearly regard his programs as competition. Whether they are gang members or not, most of the kids try out for Smith's teams. At the start of the season, 25 kids between the ages of 10 and 12 signed up to play in the C-U Youth Football League with the Warriors. This was the first time an all-black team from northeast Champaign had joined the league. They even won their first four games until the "gang bangers" on the team decided to quit. All 12 of them. "They couldn't take the weight," said Smith. "They can talk a big game, but they couldn't handle it. All of the ones in Mansard Square and Parkside [public housing complexes in northeast Champaign] decided to quit the team. All of them." He shook his head sadly. The gangs got in the way. "They were told not to get involved," he said. Even though the loss of half the team ended their winning streak, Robert continues to show up faithfully for each practice. He joined the Warriors because he wanted to play on a real football team, but the seventh grader at Edison Middle School knows there is more to it than that. "It keeps kids out of trouble and gang-related stuff," he said. The fact that the gangs join in some of the activities at the center, however, doesn't bother him. "They come and play basketball, but they don't cause no trouble." Smith's no-nonsense attitude helps ensure this, as does the

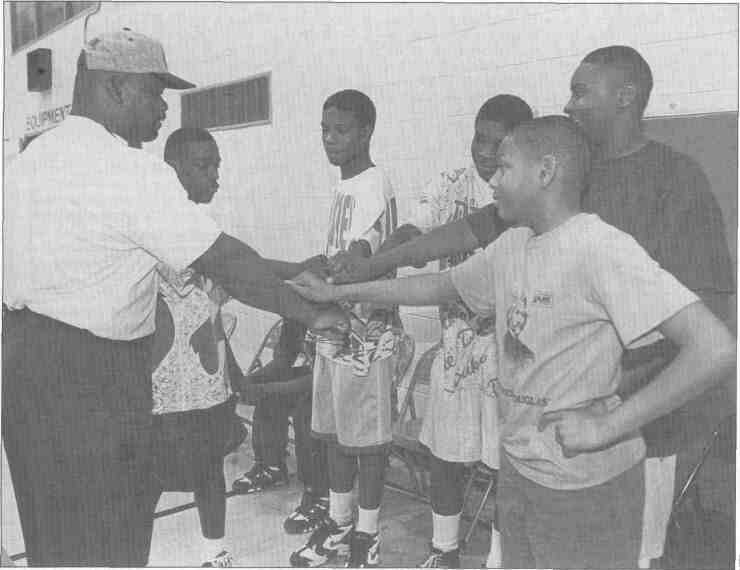

Photo by Carlos T. Miranda, a photo-journalism student at the University of Illinois Walter Smith and his "gang." Fighting the influence of street gangs is an endless battle, says the director of Champaign's Douglass Center, because there is no single, magic solution. But he believes that showing youngsters they have options in life can be a powerful antidote to the lure of street gang activity. 28/April 1995/Illinois Issues Champaign Community Policing Unit. Community policing began in February 1994 to help the residents feel more comfortable with the police and get the police more involved in the community they serve. "We try to let them know that we are human but we have a job to do," said Officer Stephens. "We'll run people up to the store to get milk for the next morning, we'll change diapers. We'll do whatever it takes to get people to know us." Stephens admits that while he can't insist that all areas be neutral territory, he can make sure that Douglas s Center remains so. "I am not going to tolerate any gang activity," he said. "If they fight, I'll shut the center down and they'll have no place to go." The way things are now, Stephens said, "It is no matter if you're a Vice Lord or a Gangster Disciple. You can go up there and play basketball and not worry about a fight. Parents don't have to worry about their kids getting shot, stabbed, run over or threatened." "We've had drug dealers come in and want to use the basketball to play outside. 'I'll give you 100 dollars'; they try to bribe me," Smith said. "We don't play that kind of stuff here. They know if they mess with us, they go to jail for a long time." Gang members or not, the neighborhood kids swarm to the park every afternoon. It is the programs that Smith initiates on his own that attract most of them. Right now he volunteers a minimum of 15 hours a week to coach the Warriors, and he had the basketball teams scheduled to play 16 games with Boys Clubs in central Illinois before he had found the players to make up the two teams. "I go out recruiting them [the kids] just like a college coach," he said. Probably the most memorable part of being on one of "Walt's teams" is the traveling. Last year Smith loaded up his old, red-and-white striped van with the 15-member basketball team and headed for Chicago to tour the Bulls Training Center. "One of the kids sniffed Scotty Pippin's shoes," Smith said, groaning. "They really enjoyed the tour, and it inspired a lot of kids when they saw that. They got to sit in the chairs they sit in, see the court, the weight room, the gigantic whirlpool." Smith plans to take the Warriors camping as a reward at the end of their season. "They never forget the experience," he said. "They never think Illinois has caves and hills and small, miniature mountains. Fear of darkness gets a lot of them." Most of the kids have never been outside of the city. The most difficult thing Smith has to work around, however, is funding. Illinois park districts are considered separate government agencies, so they are not eligible for not-for-profit grant money that often funds these kind of programs. But even the $45,000 to $60,000 a year Douglass receives from the park district does not cover the extra programs Smith initiates. The end result: a lot of time networking with community businesses and organizations for private donations that will help ease the burden on the kids and keep the programs going.

In a span of one week, Smith managed to collect $1,300 to take a boy to California for the Scholastic High School Championships in Track and Field. "I just tell them it's for the kids," he said. "This kid had an opportunity of a lifetime. And now he's gotten letters from colleges all across the country for track, from Miami, Princeton, Manhattan, Missouri, Purdue." This spring Smith is working on getting funding from Champaign and Urbana for a midnight sports night and a summer basketball league. Currently neither city is involved in the Douglass Center in any way. Although Smith agrees that his work should remain local in scope, he believes that some of these programs would be beneficial if they were expanded. "It could work," Smith said. "It's something that would force gangs to change their philosophies — you have to push them out." It is an endless battle because there is no one way to wipe it out, he said. You just have to keep fighting at it and try to show the kids that they have options. Smith has been dreaming up new ideas and methods to make them succeed for years. For the last four of those years Robert has been an active participant. Every afternoon when he finishes his newspaper route, the 12-year-old rides his bike over to Douglass for practice. "Ever since I was a little kid I've wanted to play football," he said. "And when I heard about this, I knew I wanted to play. That's what I want to do when I grow up." Although being raised in this neighborhood may have made Robert seem more grown up at 12 than many adults, a part of him fights to hold onto that child-like dream. As he speeds into the park and leaps off his bike, letting it fall to the ground with its wheels still spinning, the surrounding gangs and violence are the furthest thing from his mind. He just wants to play ball. Ginger Orr is a graduate student in journalism at the University of Illinois.

April 1995/Illinois Issues/29

|

|

|