|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By JAMES KROHE JR. Saving history from the wrecking ball

They All Fall Down documents the life of the patron saint

Hollywood would not have dared contrive such an ending to a story. Richard Nickel was an architectural photographer in Chicago. One April night in 1972, he slipped inside the ruined wreck of Louis Sullivan's Stock Exchange building in downtown Chicago, then under demolition. Newly engaged and happier than he'd been in years, Nickel had gone there for "salvage," although "thievery" is what the wrecking company boss later called it. A floor collapsed, and Nickel, 44, was dead in an instant. It took another 26 days to find his body. Death by architecture was an ironic end to a life spent cataloging and collecting the works of Sullivan and other building designers. That life is itself cataloged in They All Fall Down, Richard Cahan's account of what he calls, somewhat grandiloquently, "Richard Nickel's Struggle to Save America's Architecture." Nickel was born in 1928. A paratrooper who served in Korea, he enrolled in 1948 as a GI Bill student at Chicago's Institute of Design, where he perfected a talent for photography he showed in the Army. It was also at the institute that Nickel met his mentor, the noted art photographer Aaron Siskind, who in turn introduced Nickel to Louis Sullivan. Cahan writes that Sullivan by then dead 28 years "became a symbol through which Richard learned about the world." Nickel had a kindred sensibility, and thus was an eager pupil. Anti-religious, Nickel's response to architecture was nonetheless spiritual, even mystical. In this he resembled Sullivan, who believed that buildings were God made manifest. Less impassioned admirers are not sure how much God there is in Sullivan's buildings, but they concede that they contain quite a bit of very good architecture. The A/A Guide to Chicago, easily the most authoritative source on a crowded shelf of Chicago architecture references, includes Sullivan in its troika of founding genuises, along with John Root and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. How astonishing, then, to consider that 40 years ago there did not exist even a standard list of extant Sullivan buildings. At Siskind's suggestion. Nickel joined a class project to find and photograph the master's Chicago works. The locations of 12 buildings of 114 buildings thought to be standing were not known; by 1957 Nickel, the most industrious among them, had found nine of these. He also 30/April 1995/Illinois Issues found another 23 built projects not previously listed. That simple inventory began 20 years of often furious work. Nickel began by measuring and photographing Sullivan buildings. Nickel often set his camera up just about the time that the buildings were coming down, and soon he began returning to demolition sites at night to salvage whatever decorative bits and pieces he could carry off terra cotta, stone, metal castings to keep them out of the dump. He usually worked alone in dangerously decaying buildings, often in bitter cold. A building under the ball would not pass muster with the OSHA; his autopsy revealed that Nickel, a young man who never smoked a day in his life, suffered from pulmonary emphysema and chronic bronchitis. By 1960 Nickel had 60 pieces scattered in the backyard of his parents' house in Park Ridge, a collection comprehensive enough to offend the neighbors' suburban notions of tidiness. He began to envision a private museum to display them, but in the 1960s the salvage of historic architecture in any form was still a too-new idea, and no local museum or foundation was interested. He eventually sold the bulk of his private horde to Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, in 1965. Nickel's self-taught skill with the pry bar and chisel, no less than with a camera, proved to be a marketable expertise in a city that was tearing down Sullivan buildings as fast as they could be carted away. In later demolitions, he was paid to direct salvage efforts on behalf of City Hall, museums and universities. Mostly, however, he supported himself with odd jobs as a photographer and teacher. Much of what Nickel rescued can be seen and savored today at the Chicago Art Institute. Pieces he donated and pieces he scavenged for hire are part of the permanent exhibit, "Fragments of Chicago's Past," which hangs in the museum central staircase. (The exhibit also includes pieces originally from the SIU-E collection.) Nickel also was part of the crew that retrieved the bits of the Stock Exchange trading room that was rebuilt in the museum's east wing. The martyred Nickel is remembered today as the patron saint of the architectural preservation movement in Chicago. But he was in many ways untypical of the movement. He was an agitator, not an organizer. He was little interested in history or theory; he liked buildings more than he liked architecture. He was a political and social conservative in a crowd that in those days tended to be Hyde Park liberals or young '60s-style campus leftists who saw themselves as soldiers in a war against philistine capitalism. The movement and Nickel met in front of the 17-story Garrick Theater in 1960. Built in the 1890s as the Schiller Building, the building stood on Randolph between dark and Dearborn before it was replaced by a parking garage. The affair, according to the 1993 A/A Guide to Chicago, was a textbook example of civic barbarity. As Nickel's photos showed the world, even a dilapidated Garrick was a marvel inside and out. Nickel picketed on behalf of the Garrick one of his few public acts on behalf of a building and pelted influential s of all camps with letters. The campaign got Nickel in the papers as both a writer and as an interviewee, and earned him the grateful attention of national cultural leaders such as Lewis Mumford. More important, it spurred the creation of a legal apparatus by which Chicago

April 1995/Illinois Issues/31

might identify and protect its great buildings. Nickel was the kind of person whom every movement needs to get started, and whom every movement quickly wishes it had fewer of the impractical do-gooder. His idealistic refusal to compromise, for example, led him to disdain the dull work of Grafting and lobbying for legal protections for landmark buildings. And he denounced economics as "crap," thus failing Preservation Lesson No. 1, which is, steel and stone do not keep buildings standing money does.

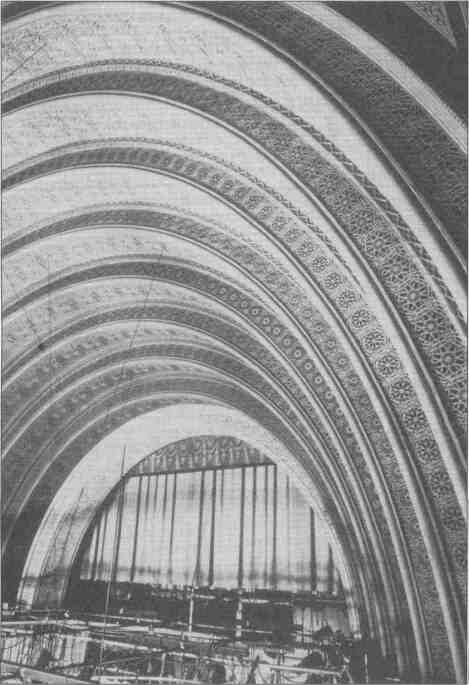

This is the proscenium arch in the Garrick Theater during the 1950s. At the time, the theater was being used as a TV studio. Architect Louis Sullivan got the commission for the building, an opera house, in 1890. By 1960, the Garrick was dilapidated. But Nickel believed that it represented the culmination of Sullivan's architectural ideas. He set about to photograph it - and to try to save it. Nickel collected with the fervor with which the faithful seek the bones of the saints. Even the people who agreed with him wondered sometimes whether he was a little nuts. However, in a town where (as architect Alfred Caldwell once said) developers can propose and city officials can concur in the leveling of a Midway Gardens to make room for a filling station, who is to say who is nuts, architecturally speaking? Agitation to save old buildings goes back a long way in Illinois. Until recently, such structures were precious not for themselves but as icons of the past, or because of the events or people associated with them. If Lincoln had taken a piss in the Garrick Theater, one disgruntled activist said at the time, they'd have no problem saving it. There was little distinctive enough about Illinois architecture as distinct from architecture in Illinois to make it worth saving until late in the 19th century. It was then that the first of the so-called Chicago style of skyscraper began attracting the attention of the nation and the world. It is hard to overestimate the importance of these structures, although it is not hard to find Chicagoans who do. If American architecture did not begin in Chicago, Chicago architecture did, and that is achievement enough. Only a few of the seminal generation of tall Chicago buildings survive. A commercial building in the United States has a life expectancy of decades rather than centuries. They fall victim to the same forces that created them in first place (the need for novelty, innovation in building systems, the press to build higher to exploit overpriced downtown land). That Chicago recycled its own past stirred no qualm at first. What was new was not just bigger but usually better than the old, sometimes gloriously so. Sometime in the late 1950s, however, people began to realize that what would be built tomorrow almost certainly would be less handsome and less durable than what it replaced. The boom years of the 1920s wreaked havoc in the Loop; "urban renewal" in the '50s and '60s leveled houses and neighborhood commercial buildings as efficiently as the Great Fire in 1871, and just about as indiscriminately. The result was described by Pauline Saliga, associate curator of Chicago's Art Institute, in a 1990 article: "Chicago has torn down more important buildings than most cities have ever had." It nearly tore down its most important one. In 1957, the 32/April 1995/Illinois Issues Chicago Seminary announced a scheme to tear down Frank Lloyd Wright' s 51-year-old Robie House in Hyde Park then as now one of the most famous buildings in the world to make room for a dormitory. That plan was thwarted, but the rumbles from Woodlawn Avenue woke up Hyde Parkers such as Thomas Stauffer and Leon Despres, who became instrumental in later campaigns to set up a landmarks commission in Chicago. Of course, any movement whose public personalities included Nickel, Wright, and Hyde Parkers confirmed the opinion held in the rest of Chicago that preservation was a preoccupation of kooks. A Sun-Times headline during the Garrick fight read, "Eggheads Plead for Culture." Since Nickel's day, preservation has gotten respectable. Whole divisions of government departments are devoted to it. Architecture has become a hobby of the educated middle classes, acting through uncounted not-for-profit groups organized to manage and restore properties. Chicago has built a thriving tourist industry on the appeal of the buildings it hasn't torn down yet. Substantial public investment (mainly in the form of tax exemptions) keeps many more of Illinois' best buildings standing than does government coercion. Are Chicago's best buildings safe at last? Have the forces that Nickel helped marshal a quarter-century ago stymied the blinkered forces of greed? The evidence is heartening. The Stock Exchange was the last building of its stature to be remodeled into rubble. A complex subsidy from the city will help finance the restoration of Bumham and Root's important Reliance Building on State Street. Plans have been announced to open Wright's Robie house as a museum, and the Charnley House, the Adler and Sullivan mansion, found a tenant in the Society of Architectural Historians, which will relocate to Astor Street from Philadelphia. Still, dozens of good buildings have been lost since Nickel's death. William LeBaron Jenney's Fair Store and the 1872 McCarthy Building were razed in the 1980s for never-built skyscrapers. Most recently, Chicago's City Council approved plans to raze the entire 600 block of North Michigan Avenue, including an interior of the Arts Club designed by Mies van der Rohe. The project's developer told the Tribune that the graceful 1920s-era buildings on the site are "not functional in today's world." He meant "functional" in financial terms; they earn only a reported 2 percent on investment. Ironic, then, that return on investment has saved more first-class buildings than preservationists. An example is The Rookery on LaSalle Street, designed by John Root. Spectacularly restored to its 1890s appearance, The Rookery's perches are filled today with investment firms, European bankers and high-end clothiers. Like its surviving kin, the building is rich in material and workmanship that cannot be duplicated today at any price. This gives them a profitable cachet in the Class A office market, where renters are willing to pay a price for a distinctive address. Such ironies abound. As part of a last-ditch attempt to save the Garrick, the city of Chicago in 1961 was asked for $5 million to buy it from its owners and convert its theater to public use. The investment was judged too costly, and when the city backed out demolition proceeded. The parking garage that took the Garrick's place has recently been bought by the city for $5 million which plans to raze it. The land, officials say, will be donated for use by the Goodman Theater company. To build a theater. Richard Nickel's ghost must be amused no end. James Krohe Jr. is a contributing editor of Illinois Issues and has written extensively about Illinois architecture.

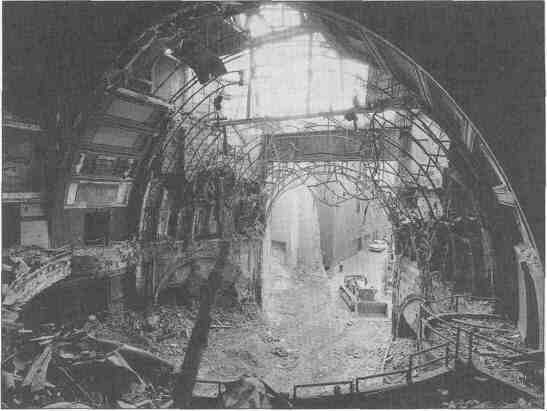

This is the proscenium arch (see previous page) during demolition in 1961. Richard Cahan is the picture editor of the Chicago Sun-Times. His biography of architecture photographer Richard Nickel, They All Fall Down, was published by Preservation Press, the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Cahan is also the author of Landmark Neighborhoods of Chicago, which was published in 1981.

April 1995'/Illinois Issues/33

|

|

|