|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By CARA JEPSEN

Balk radio

When politicians and the public meet over the airwaves,

Illustration by Mike Cramer

10/June 1995/Illinois Issues It's Monday morning and Ed Vrdolyak and Ty Wansley are in the middle of their daily WJJD-AM radio show. Callers are assessing the bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building. In fact, the bombing has replaced the O.J. Simpson trial as the topic of choice on talk shows across the nation. After all, the relationship between public affairs and radio is nothing new. As much as half a century ago, politicians recognized the power of the medium to knit the country together in times of crisis. The public responded on a mass scale, turning to radio as a way to connect with momentous events — and to one another. By the late 1940s, radio had become an electronic extension of the democratic process. But these days critics charge that the new "talk radio" has become little more than a place for the public to vent its frustrations with government, and a means for politicians to display themselves. They argue that it provides just another high-tech way to manipulate the public. And — pointing to top ratings in venom — some critics even manage to blame the Oklahoma bombing on the medium itself. Although the WJJD show tends to be moderate and playful, one caller urges swift justice. "Whoever did this, they have to die," agrees Vrdolyak. "They have to die." The former alderman's blunt Chicago accent contrasts sharply with Wansley's rich drawl, and the two often fall on opposite sides of the political fence: Wansley was a fan of the late Harold Washington — who was a liberal and the city's first African-American mayor — and Vrdolyak, a former alderman and political powerhouse in the city's blue collar 10th Ward, was one of Washington's staunchest opponents in the Chicago City Council. Vrdolyak and Wansley first hit the airwaves together in 1993. They started on WLS-AM/FM, then moved to WJJD when that station went all-talk. Their program, which features intelligent callers, amusing sound bites and the hosts' quick wit, is funny and informed. And entertaining. A former politician entertaining? Of course. Vrdolyak is one of a multitude of political operatives who have turned to talk radio, either as a second career or as a way to resuscitate the first one — though Vrdolyak swears he has no plans at the moment to return to politics. The best-known Illinois politician to go through the talk show door — and back out — was Lt. Gov. Bob Kustra, who announced last year he would resign his post to become a host on Chicago's WLS-AM. He had a change of heart before the first show aired. Even Beyond the Beltway host Bruce DuMont, who launched his political talk program on the more circumspect public channels, jumped on the campaign bandwagon briefly, running for the state Senate in 1970. "You should decide early in life whether you're going to be a reporter or politician, and once you've decided, you should stick to that track," he says. Tell that to presidential hopeful Robert Dornan, a Republican representative from California who was a regular fill-in host for Rush Limbaugh before he announced his bid for president. Others who have crossed the line at one time or another include failed presidential candidate — and failed talk show host — Ross Perot, failed presidential candidate Gary Hart, former New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, former California Gov. Jerry Brown, former New York Mayor Ed Koch, former Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo, Iran-Contra survivor Oliver North, ex-con G. Gordon Liddy and former Texas Agriculture Commissioner Jim Hightower.

"Radio turns to politicians because of two things," says WLS-AM/FM General Manager Tom Tradup. "Instant name recognition and verbal acuity. Politicians love to talk, love to debate and love to get on the air and hone various arguments about various issues." The exposure can bring electoral rewards. U.S. Rep. Mel Reynolds, a Chicago Democrat, hosted a radio show for two years on WLS-AM after losing two bids for Gus Savage's House seat. After announcing his third run for office, Reynolds stopped doing his show — and won the election handily. "All we did was offer him the opportunity to go on the air," says Tradup. "If he was terrible, we could have booted him. It was not for us to worry about what happens if he runs for office again." "If you think about it,it's a marriage of convenience for both sides," says Tom Taylor, editor of Inside Radio magazine, a leading trade publication. "Radio gets the built-in name value. The politician gets a daily platform to blast away at what he wants to blast away at. There's nothing like having four hours a day to do what you will. It's an amazing platform." Susan Herbst, associate professor of speech communication studies at Northwestern University, agrees. "It's a way to stay visible between office terms. It's a way to be part of people's lives, in a way that newspaper columns used to be a decade ago. It's a way to be there all the time." Yet, does the public benefit? The recent exchange between President Bill Clinton and such conservative hosts as Watergate operative G. Gordon Liddy over the issue of terrorism has brought that question into sharp focus. Liddy advised his listeners to fire "head shots" if they are attacked by armed federal agents. (Some stations have since cancelled his syndicated program.) For his part, Clinton told an audience in Minneapolis, "We hear so many loud and angry voices in America today whose sole goal seems to be to keep some people as paranoid as possible." He went on to suggest that some of that "hate speech" had led to the Oklahoma bombing. Clinton later denied that he was talking about talk radio hosts. Indeed, the president originally enjoyed a brief honeymoon with talk radio when he invited hosts to the White House shortly after the 1992 election. But as early as June 1994, he was quoted by The Associated Press telling a host from KMOX that "much of talk radio is just a constant, unremitting drum-

June 1995/Illinois Issues/11

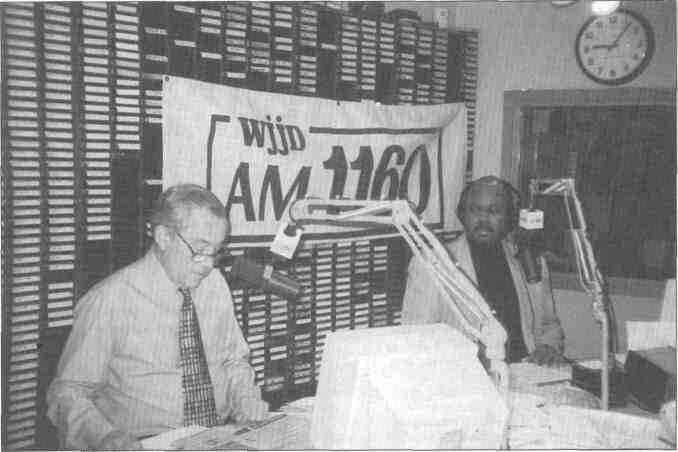

Photo courtesy WJJD Radio

Former Chicago Aid. Ed Vrdolyak (left) and Ty Wansley first hit the airwaves together in 1993.

KMOX-AM Program Director Tom Langmyer doesn't see Clinton's comments as a threat. "I think that [Clinton] is expressing his opinion, but the fact is, he knows that the First Amendment is an extremely important issue, and I don't think that he would want to hinder that in any way," he says. Langmyer's St. Louis-based news-and-events-driven talk station carries Rush Limbaugh middays and reaches a large section of downstate Illinois. The political roots of talk radio Political talk radio has a long history. The first scheduled, non-experimental public radio program in America was a broadcast of results from the presidential election between Warren G. Harding and James M. Cox on November 2, 1920, on KDTA in East Pittsburgh, Pa. Comedy, drama and sports programming soon followed that historic broadcast. But politics continued to play an important role in the development of radio. Harding was an avid supporter of the new medium, which he helped to legitimize with his 1921 Armistice Day speech, the first coast-to-coast address by a U.S. president. President Calvin Coolidge continued the tradition, making three separate radio speeches during his first three months in office. In a precursor of things to come, Coolidge made use of radio during his re-election campaign, including a dramatic election-eve broadcast. "Coolidge found early radio flattering to his flat, soft voice, and effective in reaching a maximized audience with a minimum of effort," writes J. Fred MacDonald in Don't Touch That Dial: Radio Programming in American Life from 1920 to 1960. "One contemporary observer, Charles Michelson of The New York World, suggested that, given Coolidge's weak physical appearance, it was his voice that actually carried him to election victory." Politicians continued to find radio's intimacy useful, from Franklin D. Roosevelt's legendary fireside chats to President Clinton's addresses. The transmission of such events as the explosion of the Hindenburg and Edward R. Murrow's World War II broadcasts from London utilized the medium's immediacy to create community among Americans. In many ways, radio has provided the fodder for discussions over the backyard fence. But talk radio has begun to replace that backyard fence as more Americans turn to the medium to debate such issues as the Oklahoma bombing. 12/June 1995/Illinois Issues

Liddy and other political-figures-tumed-hosts joined the ranks of issues-oriented talk shows in the wake of the popularity of conservative host Rush Limbaugh's program. Limbaugh airs on some 660 radio stations nationwide. In the past five years, the number of U.S. radio stations with talk-show formats has more than quadrupled, from 200 to 1100. About 20 stations a month switch to an all-news or news/talk format, according to Robert Unmacht of M Street Journal, a publication that tracks radio station formats. In Illinois alone, there are 56 news/talk stations. Unmacht says one of the reasons so many stations are turning to talk is that satellite and syndicated programming is relatively inexpensive, compared to the old practice of hiring several full-time news people. In addition, a talk format — as opposed to music — is more profitable. The format makes it easier to run more commercials without alerting the audience. Evergreen Media Corp./Chicago President Larry Wert's radio station, WLUP-FM, went from a mix of music and talk to entertainment-oriented talk last year. "Listeners are participatory, so it's a more effective advertising medium," he says. "We can run more inventory than a music station. Since we've done this in the last year and a half, we went from $12 [million] to almost $20 million in billing." The demographics of talk radio Who listens to talk radio? "Research shows that the kind of people who listen to and participate in these shows is a very selective group," says Doris Graber, professor of political science at the University of Illinois at Chicago. A 1993 study by the Times Mirror Center for the People and the Press found that talk show listeners voted Republican by a three-to-one margin. The study also found that conservative listeners outnumber liberals two to one. Conservatives are more likely to call in when they listen, and are more likely to get on the air. Today's talk radio shows provide an electorate that's fed up with media and politics as usual with a forum to vent their frustration and reach other like-minded listeners. Northwestern's Herbst says that part of talk radio's success is related to a weakening of the two-party system. "The political parties no longer channel discourse and get people excited about issues," says Herbst. "Now they have less and less control. People split their tickets. I think talk radio has taken up some of that responsibility, organizing and challenging political discussion. That's an interesting development in American politics. You're wondering where all the energy went that used to go into the party, and a lot of it has gone into talk radio." "I think talk radio is popular today because it plays on the strength of a medium that has the ability to communicate one-on-one," says Bruce DuMont, host of the nationally syndicated WLS talk show Beyond the Beltway. "Public opinion on the national [television] networks is determined by the Sunday morning talking heads. Not all wisdom rests on the banks of the Potomac. People are fed up with politics as usual and media as usual. Talk radio is an antidote to that." DuMont, whose program airs in state capitals across the country, says the real political story is increasingly at the state level. He believes that talk radio will follow as politics decentralizes. "One nice function of talk radio is that it does link disparate people together in a way that they feel like they are participating in political discourse," says Herbst. "It has a sort of ritual quality to it. They don't get anything tangible out of it. It's not to persuade, but to be a part of the process. More talk can't be a bad thing. No matter how ideologically screwy it is, it's got to be good for people to vent and connect." Radio as a political organizing tool In fact, voters who believe they are disenfranchised can be empowered by radio. For example, African-American talk radio in Chicago, and particularly WVON-AM, was instrumental in the late Harold Washington's 1983 bid for mayor. For starters, television is expensive — political consultant Don Rose says that a candidate with unlimited resources may spend $1 million on television ads and $150,000 on radio in a single campaign. Meanwhile, the circulation of the black press in the city. The Chicago Defender, is small. So Washington decided to target radio. The campaign began by spending $200,000 on voter registration ads in the fall of 1982. In addition, it produced free "get out and vote" public service announcements. They were followed by more ads after the primary. The campaign spent just under $1 million in primary advertising. Campaign organizers also had their network of supporters call in to such talk radio shows as black activist Lu Palmer's program on WVON. As a result, Washington's grass-roots support in the black community flourished. In the meantime, no one in the mainstream media was listening. "From the perspective of white media people and white opinion networks, this could have been the Swahili network," says Harold Baron, who was Washington's director of issues research and is now a visiting scholar at Northwestern University. "They did not know this communication was going on. It just swamped them. Their polls could not pick it up because they under-sampled people who listen to black radio." According to Gary Rivlin in Fire on the Prairie: Chicago's Harold Washington and the Politics of Race, "Black turnout [in the primary] was an incredible 85 percent — two percentage points higher than the white registration. Washington won over 99 percent of the black vote. ..." Indeed, white politicians began targeting the African-

June 1995/lllinois Issues/13

American radio audience in the early '80s. Gov. James Thompson advertised on black radio in the 1982 and 1986 campaigns . Other mainstream politicians soon followed suit. While African-American voters found a representative in Washington in 1983, talk radio helped unhappy conservatives find a voice to oust Democratic incumbents in the last election. "There is clearly an organizational structure for what happened in 1983," says DuMont. "The same thing could be said for politics in 1994. Conservative people got fed up all over the country and found a common denominator in Rush Limbaugh and others who were an outlet for that frustration. Blacks in Chicago in the 1980s and conservatives in the 1990s probably felt that the mainstream media was not listening to them. In 1983 and in 1994, talk radio was not just a sounding board for opinions, but it also told people to go out and vote, to throw the rascals out. ... Talk radio has been that open line where people can share their frustrations." But what happens when frustrated callers recite so-called "facts" that have little basis in reality? Anonymity ensures that talk show callers are accountable to no one; unlike the backyard fence, there isn't anyone checking facts and pointing out faulty reasoning. "The danger is when people think they're authoritative," says the U of I's Graber. "People who call in have no responsibility for what they're saying, so they say things that are totally wrong and totally out of context. And radio gives more authority to what they're doing." Political consultants have a trick bag full of strategies for manipulating the anonymity of the medium. Campaigns often use volunteers and paid workers to call talk shows and push a particular agenda. The built-in anonymity of the medium makes it impossible to identify which callers are "real" and which have a hidden agenda. "You try to get them to call in and make a point," says Don Rose, a veteran consultant who was instrumental in getting Jane Byme elected Chicago mayor in 1978. "For example, when the opponent is on the air, they may call in and say, 'You're a damn liar.' Their roles can be argumentative and so on. Sometimes they will call in to someone on WGN, say, who isn't necessarily doing a political show but talking about traffic. The person will say that the traffic is pretty lousy, but Joe Blow has this great idea for easing traffic. If the producers of a show are savvy, they'll screen calls until they get someone from the other side." Talk show producers determine who gets on the air, and they do the bidding of the talk show hosts. For example, listeners never know how many callers who don't agree with the host call the program; chances are, they won't make it through the screening process. Unless, of course, the host wants to engage in an on-air argument. Assessing the impact

Clearly, talk radio has had an impact on politics and

Photo of Bruce DuMont courtesy of the

14/June 1995/Illinois Issues government. And the medium's role appears to be growing. "I believe that Limbaugh had a profound effect on the November election," says Steve Rendall, senior analyst for Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting. "It may have meant that only a quarter of a percent voted the way they did because of Limbaugh, but he affected the debate in other ways by shifting it to the right. Then you had people like Cokie Roberts of National Public Radio telling Clinton he should move to the right." Hosts, like Limbaugh, do influence elections, or take credit for influencing them. Take Springfield's One-Eyed Jack (whose real name is Donald Jackson), an unabashed conservative Republican. He credits his morning show on WMAY-AM with electing the capital city's mayor. Republican Karen Hasara. (A Hasara aide says he can't take total credit.) "We asked [Democratic incumbent Ossie Langfelder] time and time again to come on the show," says Jack. "We finally said we would throw this guy out of office. We used to count down the number of days he had left in office." Jack says he tries to encourage listeners to be politically active. "We get a lot of people who will call in and say, 'That's politics as usual,' and I will say, 'If that's true, it's your fault.' If that were the case with medicine or the space program, we'd have both feet planted firmly on planet Earth. We try to get people pumped up. Our goal is first to get them to think, to make a decision and then act on it." Of course, it doesn't hurt if the listener is in tune with Jack's political agenda. New York City shock jock Howard Stem, whose show is syndicated to 20 cities (and who toyed with the idea of running for mayor as a Libertarian candidate), supported Clinton for president and claims partial responsibility for his 1992 victory. "I'm going to get behind anyone who can help me with this FCC crap," he said on his show recently, referring to obscenity charges leveled against him by the Federal Communications Commission. "That's who my allegiance is to." Conservative New York City talk show host Bob Grant is credited with being instrumental in the election of that state's Republican U.S. Sen. Alfonse D'Amato and Mayor Rudolph Guiliani, as well as New Jersey Gov. Christine Todd Whitman and New York Gov. George Pataki. "Each during their respective victories called him on the air and thanked him profusely for helping with their victories," says Rendall. He points out that Grant's views tend toward extremism and that while politicians welcome his support and appear on his show, they also try to distance themselves from some of his rhetoric. Grant once referred to an African-American congressman from Harlem as a "Pygmy." "The way that talk show hosts like Grant operate has a malignant effect on the political system," says Rendall. "Both he and Rush play on political prejudices, although Limbaugh tends to play up economic resentment even more." Despite radio hosts' claims about furthering political participation, Northwestern's Susan Herbst is cautious. "I think, overall, talk radio is positive," says Herbst. "But I worry that it replaces actual activity. Talk radio is such that you can sit in the house alone and anonymously call in and say your opinion, but you don't have to put anything behind it. You don't have to invest anything. That's the only worrisome aspect. Talk has a place in democratic theory. But you don't want to have all talk in place of people getting out there and protesting, voting and doing all of the standard things that make for a democracy." The bottom line is entertainment The most entertaining and successful hosts today are conservative — from One-Eyed Jack in Springfield to Rush Limbaugh. Herbst says that while there is no shortage of liberal talk show hosts, conservatives tend to be more charismatic. "Rush succeeds because he's a terrific entertainer," says Tom Taylor, editor of Inside Radio magazine. Taylor notes that Limbaugh had a track record as an FM music deejay before turning to political talk. "If you went to the core of what he's saying, I don't think he would do as well." In fact, talk radio is on the air for one reason: It gets the ratings. "Whoever is calling, and whatever the topic, a primary function of talk radio is that it must not be boring," says Taylor. "It's got to be entertaining. If you listen to Rush's show when other people fill in for him, it's a completely different show.

[Presidential hopeful] Robert Doman occasionally would fill in. It gives you a real chance to see what a dedicated right-wing ideologue who's not a particularly great entertainer sounds like. There are not a lot of people who can perform at Rush's level." Limbaugh has worked for years to perfect his craft, and politicians like Ross Perot — who recently terminated his syndicated talk show — have found that the shoes of a talk show host are hard to fill. So who should take responsibility for talk radio's nearly one-sided viewpoint? WLS-AM/FM General Manager Tom Tradup says the responsibility lies with the audience. "I think you have a problem when a radio station tries to police the morals of a politician, or when it tries to enforce some type of ethics code of its own to the detriment of public debate," says Tradup. "I think our responsibility is to deliver the largest possible audience to our advertisers. And the way to do that is to deliver the most entertaining radio possible to our audience." Meanwhile, back at WJJD, Vrdolyak and Wansley are preparing to wrap up another daily segment with their theme song Don't Worry, Be Happy. The right to carry a concealed weapon — a hot topic in the wake of the Oklahoma bombing — comes up before the last call is taken. It's likely to fill lots of airtime on future shows. * Cara Jepsen is a Chicago-based free-lance media writer who specializes in covering commercial radio. Her articles have appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times, the Chicago Reader and New City.

June 1995/Illinois Issues/15

|

|

|